[22 May 2017: We are deeply saddened to learn that Mike has passed away. If you don’t know his work, we invite you to dive into Mike’s website and learn about his tremendous research, writing, and impact. —ed.]

I finally seriously joined EPIC. By “seriously” I mean “sent them money.” It was high time. I’m a creole with academic, applied, and practitioner ancestry. As a practitioner over the last several years, I’ve been wildly successful working on a specific local problem and a spectacular failure at approval for the results of that work from higher levels of the bureaucracy. Most of this work was in the area of social services. There is a correlation here between local success and distant failure that’s fairly typical of social services. It might be that a social services focus differentiates the work I do from the usual EPIC project. More on that in a moment.

First some background on the “I” in EPIC. It stands for “industry.” My work in the world of commerce is limited, to put it generously. I’ve always been better at losing money rather than making it. So, other possible meanings of that “I” tend to jump out. It could also stand for “informatics.” EPIC has an origin story in tech – founded by ken anderson at Intel and Tracey Lovejoy at Microsoft and initially funded by those companies. And a significant part of the membership today works in tech industries (it’s also true that companies that didn’t used to think they were part of the tech industry now do). But tech doesn’t dominate EPIC; far from it. Over a decade, other concepts have flowered in the EPIC landscape, concepts like “design” and “user experience,” both of which I’ve used promiscuously and probably incorrectly. But these concepts, too, often incorporate informatics as part of their process or project goal. I like this ambiguity in what the “I” might mean. It calls attention to the fact that most problems a practitioner works on involve information flow in a blurred mix of human and digital voices.

Another meaning of the “I” in EPIC could be “Intentionality.” I mean this ambiguous bit of philosophical and social science jargon in the sense originally proposed by its creator, Franz Brentano. He and Wilhelm Dilthey were two of the critics of the Enlightenment-driven experimental laboratory version of social science growing up around them in the 19th century. Intentionality meant that no description or explanation of humans was possible without attending to their beliefs, emotions, desires, and purposes, and, as Dilthey added, history and lived experience. Brentano’s arguments turned into phenomenology, via his student Husserl, an important philosophical foundation for the kind of work that EPIC people—and many others—do. It was an argument for a different kind of science, the kind that EPIC puts into practice.

This “different way of doing things” is part of what EPIC means to convey with that initial “E,” as in “ethnographic.” I’m not sure that the “E” is such a good idea anymore though. Because of its long history in anthropology and sociology, use of the term, in my experience, inspires arguments about what “ethnography” actually means that impede rather than enhance communication with project colleagues. In my practitioner days, I just said that what I did was a different or alternative kind of social science by way of opening a conversation about what it is, rather than whether or not it is really “ethnography,” or “qualitative research,” or “science” for that matter. (I sometimes used a “family therapy” metaphor to get going, but that’s a topic for another day.)

The language game of making the “I” in “EPIC” also stand for informatics and intentionality helps flesh out the character of the organization. (A friend suggested I continue the game by making the “C” stand for “creole,” but that’s enough for now.) The meaning of the “I” that I have trouble with is the one that the founders intended, namely, “industry.” Not that there’s anything wrong with that, as Jerry and George said in the famous Seinfeld episode. Unless, of course, you’re a tenured humanities/social science academic with a guaranteed automatic monthly deposit to your bank account, in which case “industry” might well mean a naïve diatribe that you sold out to the lackeys of the running dog imperialist oppressors of the people.

I’m as fed up with the 1% and the disparity of wealth and the Wall Street robber barons as anyone else. Still, one of my first real world ventures in the 1990s was helping found a new company in Mexico City to rebuild diesel engines. Had we succeeded, we would have contributed cleaner air to a polluted city at a reasonable cost to fleet owners with returns from increased fuel efficiency. Unfortunately, the American partner was a thief and the Mexican partner was a spoiled brat. The competent Mexican manager resigned in disgust. The Mexican lawyer and I did our jobs but the company never got off the ground. A thief and a brat were not the right leadership styles to develop the social economy. The point is, my version of socially oriented practice has plenty of room in it for the market. Right now I’m working on water governance, and “governance” means networks that include markets. Besides, as a freelance practitioner I had met the market and it was I. I was always paid for my work, wasn’t I? Never on time, but eventually?

A focus on “industry” doesn’t bother me on ideological grounds, though “business” might be the better term. What bothers me is that both terms—“industry” and “business”—are too limiting, not general enough for the epistemological tidal wave spreading across organizations in every domain, including those in social services.

When I look at EPIC, I see intellectual innovation anchored in real-world problems, where “real-world” means a critical mass of people that, whatever their different interests might be, acknowledge that they have a problem in common. I also see the mistaken theory/practice distinction fade in the rearview mirror with the knowledge that both are part of the understanding of any task. I see it taken for granted that the discourse crafted to handle a problem will be transdisciplinary and plurivocal rather than bounded by the language and interests of a small group of like-minded people. Check your boundary marking jargon at the door.

This sea change obviously isn’t just about business or industry. For the past several years, I’ve mostly done short-term consulting projects with social service organizations. I learned to think of that work—and present it to my audience so that it made sense to them—as organizational development based in complexity theory. In some ways, what I did linked to core areas of interest in traditional applied anthropology—education, healthcare, and the like. In other ways it was very different, because—the usual practitioner’s lament when encountering the academically oriented—it wasn’t “research” in any traditional sense of the term. In process, it was more EPIC-like than academic-like, which is another reason why I decided I needed to become an EPIC member. I used a different vocabulary, like “positive deviance” and “leverage points,” concepts from the world of organizational complexity. But the family resemblance between what I did and what EPIC people do was obvious.

The problem is that industry or business is not a sufficient model. Peter Drucker wrote about this long ago in his classic book, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Many others have noticed. For example, when I moved to New Mexico 10 years ago, I told a colleague who ran the Business Roundtable at the Santa Fe Institute that I was going to rob complexity concepts from the rich (ie, business) and give them to struggling social services, the poor. He just laughed, in a friendly way, but laughed all the same. “They (social services) can’t adapt,” he said.

What did he mean by this? As the heroin addicts I worked with years ago used to say, “Money talks and bullshit walks.” Here are a couple of ideal types based on Drucker’s work. Business has a bottom line. It is both a compass to guide decisions and the goal for the organization. Social programs don’t have a bottom line. They have a budget. It comes from somewhere else, usually from a higher node in the bureaucratic food chain or from an external source like an NGO or from other donors who, like the previous two sources, have their own vision of how the organization should function.

Many conditions come with a budget, emphasis on “many.” The conditions that the external sources impose on the budget mean that they micromanage the process and require frequent performance measures that are either irrelevant or that actually obstruct the local compass and goal of the social program, made all the more complicated when several funders are involved who have different visions of what the program should be doing. In worst-case scenarios, all too frequent, the conditions block the development and implementation of recommendations for change to bring local context and remote budget into a more coherent relationship. The primary purpose of the project becomes, satisfy the conditions that arrived with the money from the external source and neglect whatever motivated you to work in the program in the first place.

This is why I wrote earlier that I’m a success in the space of a local problem and a failure in the space of convincing an external source to change its funding conditions. Local colleagues, with the help of a sympathetic listener, usually figure out the problem and some creative ways to deal with it. But the local program relies for its budget on distant sources with their own complicated histories and politics and rules about how things should be done. Because the solutions we come up with require changes in the conditions under which the external source provides the budget, nothing changes locally. As the historian of business Alfred Chandler wrote, structure follows strategy. If you want to change the way you do things, you change the structure of the organization within which the changes will be made.

The “money talks bullshit walks” crowd aren’t particularly interested because their structure is not local program structure. They might even be downright offended that their image of the program looked flawed to those with local experience. Like my colleague from the Santa Fe Institute said, “They can’t adapt.” Actually, “they” can adapt at the local level, where the program and its clients are located. But “they” can’t, more often than not, in the remote places where the budget and its conditions originate. This, as far as I know, is not a central issue in the EPIC community, though I can imagine that in mega-corporations something similar occurs as well. I’ve heard stories from insiders that begin with a four-letter word or its derivative followed by “corporate.”

One way I’ve worked on this difference is to ask my clients, “What is the social services’ equivalent to the bottom line?” In other words, “What changes in your clients’ world make you think you’re on the right track?” Or, “What gets worse and makes you think you’re on the wrong track, and what do you do about it?” Most everyone in the local context knows the difference and can describe it. The problem is never that they’re not making enough money. That’s not the point of what they do. Adam Smith pointed out long ago that many important functions of the state are not well served by the market. Most health economists, for example, say that about healthcare. With local social services, the metaphorical bottom line is going to be a function of local context, and it won’t be measurable with a ratio of revenue to expenses. The failure of external funding sources to recognize this is what generated most of the jobs I did as practitioner.

The traditional response in anthropology has been to moan and bitch about how the external sources don’t pay attention to us, how if they only did, the world would be perfect. Fat chance. Even a President who learned anthropology at his mother’s knee couldn’t accomplish that. It would be an interesting problem, I’m thinking, for an organization like EPIC to take on. To do so, though, they’d have to increase their constituency in non-industry/business contexts.

Maybe the name could be changed from EPIC to EPOC, from “industry” to the more general “organization.” Just kidding, changing the name would be a bad idea. In a weird way, though, that would recapitulate the founding of the Society for Applied Anthropology after World War II. They called their journal Human Organization to make it clear that they wanted the new organization to include people from all over academic, practitioner and client networks, people working in settings other than the traditional “third world” village. In the end the goal failed. Nowadays most of the membership and the authors in the journal are from academic anthropology. In fact, recently the journal published a special issue called “Applied Anthropology in the 21st Century.” All the authors were anthropologists. I was the only one not based in academia, and, as I said at the beginning of this blog, I’m a creole with plenty of academic miles on the odometer.

Maybe EPIC could pick up on this lost dream and carry us forward into an intentional and informatics approach to local organizational context for the future. And include more implementation issues (another “I”?) when the compass and the goal are in dispute. They are already doing it with business and industry. Why stop there?

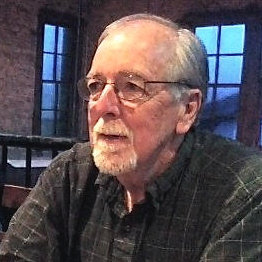

Michael Agar has been around the ethnographic block a few times, as practitioner, researcher and professor. A PhD in linguistic anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley, he took an early exit from academe in the mid-1990s to work independently as Ethknoworks LLC, now in New Mexico. He has worked on several projects—short-term, long-term and terminal—and written several books and articles developing and making use of an anthropological perspective in many domains, such as substance use, organizational development, computer modeling, knowledge transfer and, more recently, water management. Recent efforts include the 2013 book The Lively Science and a five-part series of blogs last year for Savage Minds called Rewind And Fast-Forward.

Michael Agar has been around the ethnographic block a few times, as practitioner, researcher and professor. A PhD in linguistic anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley, he took an early exit from academe in the mid-1990s to work independently as Ethknoworks LLC, now in New Mexico. He has worked on several projects—short-term, long-term and terminal—and written several books and articles developing and making use of an anthropological perspective in many domains, such as substance use, organizational development, computer modeling, knowledge transfer and, more recently, water management. Recent efforts include the 2013 book The Lively Science and a five-part series of blogs last year for Savage Minds called Rewind And Fast-Forward.

Related

The Future of Anthropology, Ed Liebow

0 Comments