Time, budget, and resource pressures will impact ethnographic work into the foreseeable future. As “de-skilling” threatens ethnography—disrupting an integrated, holistic approach and output—we must seek new work practices. We have advocated and implemented an explicitly integrative model of collaborative practice, which interconnects the knowledge domains within a cross-disciplinary team to generate effective, powerful insights. This model, which we will call hyper-skilling, focuses on assembling knowledge and communication with other key perspectives such as branding and marketing strategy, historical analysis, trends forecasting, and in many cases design and engineering. Each plays a key role in determining a company’s course of action. We also argue that the multi-disciplinary team model is well-suited to corporate settings and the conditions in which ethnographers are increasingly asked to practice. Intended or not, academic environments tend to promote the isolation of individual practitioners and the atomization of their work within specialized theoretical contexts. If instead these environments could be constructed to foster a team model, ethnographers will be better able to address challenges they face as practitioners in industry.

INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF DE-SKILLING

Like many listeners, we took great interest in Jerry Lombardi’s call last year to address the “de-skilling” of ethnographic labor in corporate contexts (Lombardi 2009). The main point of the argument was that ethnography—under pressure from the time and resource constraints that industry inevitably demands—is facing simplification, standardization, and reduction to piecework status. In the process, it loses the very qualities which industry values and seeks in ethnography, defeating industry’s own objectives. Ethnographic practitioners meanwhile grow alienated from their labor. De-skilling demoralizes them and exerts a depressive effect on their creativity. Contextual understanding is eroded as discovery runs on an assembly line.

In this paper, we suggest that collaborative work offers an effective response to this challenge; not just collaborative work in general, but work that gives ethnographic practitioners an explicitly integrative role. In the context of innovation, the role ideally goes beyond situating observations in a cultural context, to the active coordination of input from multiple disciplines such as business strategy, communications design, product design and market and lifestyle trends. Each discipline has its own body of understandings that an ethnographer must interpret and articulate back to the innovation effort. A road to practical effectiveness (and professional fulfillment) lies in recasting the role of the ethnographer as inter-disciplinary mediator.

Others have looked at collaborative ethnographic work before, particularly in the context of design (Dawson 2002, Wasson 2002, Sacher 2002). All agree that effective collaboration requires a great deal more than the collaborative “tools” of common workspaces, artifacts, deliverables, and the like. The real engine of effective collaboration is a common conceptual apparatus linked with integrative work practices.

In this paper we will build on that thinking and take it a step further. Collaborative concepts and processes are a resource for enriching ethnographic knowledge and skills. Considering our own experiences at a 25-year-old design innovation firm, we suggest that a way forward—and against the threat of de-skilling—is to re-assert the holistic perspective at the heart of ethnography, and to re-animate it in new forms of collective practice. We will call this approach “hyper-skilling”.

HYPER-SKILLING

De-skilling is a genuine industry concern. And yet consider for a moment the perspective of an ethnographic team that found itself experimentally re-crafting its members’ roles. Depaula, Thomas and Lang (2009) of Intel explain how they shifted into various strategic roles at the company to insure that their ethnographic work drove the innovation process and its outcomes. “As we narrate our own trajectory…from simply ‘informants’ to product and business strategists to dealmakers,” they write, “we come to realize…profound transformations in our ethnographic doing and knowing…. We reached and experienced new forms of ethnography that the ‘founding fathers’ of this discipline would have never imagined.” (Depaula, Thomas and Lang 2009)

The roles played by the Intel ethnographers migrated in response to “pull” from the rest of their team. They had to learn about competitive market intelligence, business strategy, engineering, and more—not to replace these functions, but to effectively articulate their own contributions. The result was a transformation of their practice, creating a sense of increased relevance. Circumstances are never identical, but in essence that is the kind of experience we are talking about. In collaborative, interdisciplinary ethnography, what happens is not de-skilling, but hyper-skilling.

Simply put, hyper-skilling means finding and using clear lines of sight to the efforts of others working on the same problems from different perspectives. The term reflects a magnification of effectiveness that can occur when those sight lines converge in powerful new ways. At least two basic benefits emerge. For industry, hyper-skilling makes the findings of ethnographic practice more actionable, by including more of the relevant knowledge domains needed to solve a problem. For individual practitioners, it pushes them beyond their usual range, enriching and extending their interpretative skills, capabilities, and knowledge.

An innovation firm such as Ziba Design is a good place to explore the potential of such an approach because its focus is inherently integrative. It focuses on “experience design,” the premise of which is the tight organization of offers across multiple touchpoints in a consumer’s experience. The business must express its purpose, identity, and value across these touchpoints in a meaningful and harmonious way or it will falter in its relationship with its audience. Clarity and consistency across the experience is essential. In all cases, the focus of these integrative efforts is the business’ brand. Thus, much of the language at Ziba focuses on “authenticity to brand,” both in our publications as part of our internal work practices.

“Consumers seek meaning and a brand they can trust,” writes Ziba founder Sohrab Vossoughi. “They are creating ways to cut through the noise in search of products and services that resonate with integrity and transparency: in a word, authenticity.” (Ziba 2007) Trust in brand is also more universally recognized as the key to experience integration. Brand character expert David Altschul writes for instance that, “A brand is like a character in the drama of its category…[One] is suspicious of any character whose motive is not clear.” (Altschul 2009) Of course, the words “integrity and “integration” both derive from and share roots in the idea of wholeness; experience design must create interconnections to establish the perception of brand unity in consumers’ minds.

That is why our work practice is becoming increasingly cross-disciplinary. It experiments a great deal with new integrative concepts and structures. Its teams strive to “connect the dots” to insure that a company’s brand expresses its promise correctly across potentially disparate experiences, which include new products, physical retail environments, communications, online purchasing, customer service, and so forth.

Without integrative structures, such a firm would have to rely only upon individual genius to work across multiple, diverse consumer touchpoints with any success. And while there was a moment at which that may have been said of the company (indeed, it has been said [Byrne and Sands 2002:59]), Ziba numbers over 100 staff these days, with 10 creative directors orchestrating many teams across diverse projects. The genius model cannot dominate its practice.

A case study of our recent work with Chinese athletic apparel manufacturer Li-Ning illustrates some of the core conceptual apparatus and processes surrounding our current model of ethnographic work. Within it, a hyper-skilled approach has emerged vividly—albeit imperfectly at times, and still very experimentally. To set the stage for that discussion, some background on the project is needed.

THE LI-NING CHALLENGE

Li-Ning is the third largest athletic retailer in China. It originally approached Ziba for little more than a handful of youth-oriented designs. At the time (2007) it was 17 years old. Its founder, Mr. Li Ning, was a sports superstar who had won 6 medals at the 1984 Summer Olympics in gymnastics.

The company just wanted some of its clothing and footwear to be considered cool. Because at the moment, Li-Ning’s wares were patently uncool. “When we look around,” its Marketing VP said of the teenagers and 20-somethings he wished to attract in China, “none of these kids are wearing our stuff. They’re all wearing Nike and Adi (Adidas). So how do we get them to start wearing Li Ning? What can you do for us that will get them to pay attention?”

This wasn’t something that a handful of new styles could cure. Li-Ning had been losing ground to the bigger players from the West for some time—since the company’s beginning, really, back in 1990. It had done well enough in those early years just by providing quality at the right price, as a less expensive alternative to the Western giants. But now it was struggling as the market matured. The upcoming generation remained an enigma to the company, and its existing consumer base was getting more sophisticated. Local upstart companies were also posing a threat. Smaller and more agile, they exhibited a tremendous talent for copying designs and selling them fast and cheap, effectively squeezing Li-Ning from the value side.

Considering all this, we urged them to not worry about finding a new angle on cool, but to focus instead on making the Li-Ning brand relevant to a new generation of Chinese kids. What was Li-Ning about, other than being big, successful and Chinese?

Based on early reconnaissance at retail, kids in the stores seemed appreciative of Li-Ning’s quality and consistency, and were glad to have a Chinese option. But they were not passionate about Li-Ning. Back at corporate headquarters, everybody seemed to have a different take on the brand’s essence and character—not a good sign. Where was the sense of definition that could support a deeper engagement with the brand? The company had global ambitions, but it was hard to see how it could go anywhere until it defined its meaningful core. If Li-Ning’s strength wasn’t evident at home, how could it travel outside China?

Fortunately for them, Western brands were not yet fully connecting either. Nike, Adi, and Puma were selling prestige and a piece of America or Europe. But a new generation was clearly moving into place: Gen Y, the children of China’s one-child policy, who had never known life under Communism. Surely these Chinese 20-somethings, contemplating a new era heralded by the Beijing Olympics and the Shanghai Expo had higher aspirations for sport in their lives?

Company executives acknowledged all of this reluctantly; especially problematic were the issues around brand definition. But despite the obstacles, they sensed that this was a rare opportunity to develop a unique relationship with the emerging generation. They rose to the challenge, aiming to become the first athletic retailer that understood the values of China’s emerging youth market, and to build a new product strategy aligned with that understanding.

For Ziba, taking this on meant building an entirely new understanding of modern Chinese identity as it related to sport. Few models existed for the crucial 14-25 year old group, and those that did were too simplistic to be useful. If we were to help, we would have to start from scratch. And we would have to find answers fast, compressing into a matter of months a study that justified years of dedicated effort. “We want to stand on the shoulders of giants,” said the CEO on deciding to move forward with the project. “What western sports companies took 60 years to achieve, we will need to do in six.”

HOW TO GET HYPER-SKILLED

Hyper-skilling, as we have said, preserves and enhances ethnography’s value to industry and the anthropology/ethnography profession in the face of just such constraints. We were able to realize this to a significant degree in the ensuing study. Where we could not, it helped us better understand the ideal. In what follows, we will describe the core elements: a collaborative definition of insight, team integration around the consumer worldview, intellectual resource management, and envisioning the endpoint upfront.

Insight = intersection

The crucial ingredient of a hyper-skilled team is conceptual rather than human, in particular the concept of “insight.” Insight is not a precursor to an individual “epiphany” (Wilner 2008), but the ultimate distillation of relevant knowledge needed to solve a problem. From here on we use the word as a term of art, reserving it for special use and building other terms and concepts around it.

To qualify as an insight, an idea has to have two essential qualities. A) It is actionable, or potentially actionable. One can demonstrate it could reasonably shape a product or service or space. B) It is integrative. It can deliver something important from all key perspectives.

For example, it is a fascinating and rich observation that when given the projective task to draw the Li-Ning brand as a person, people drew an image of a schoolgirl or boy or someone with relatively small stature and power. Li-Ning meant potential. It meant latent growth, an ascent that was expected to be gradual, and hinted at qualities of innocence and goodness. But that was not an insight. The related insight was that Li-Ning can help people “define themselves through their game.” This formulation reflects a shared interest between Li-Ning and its consumers in self-definition and progressive self-reformulation, a concern which is much closer to product and communications concepts than the observation about how the company is perceived. It “speaks the language” of brand, design, and consumer worldview at the same time.

An idea whose potential actionability cannot be readily demonstrated gets put in the parking lot of interesting observations. It is neither ignored, killed nor erased, but it doesn’t make it to center stage either, where it could be identified, memorialized and carried through as a central hypothesis for innovation (through a wiki, for example, or other running documentation of core project hypotheses—more on that in a moment). An idea also won’t make it to center stage if it represents only one disciplinary viewpoint without demonstrating linkages to the others, including at a minimum, to the consumer worldview. We can now describe how that role began to assume a special place in the collaborative process.

Consumer worldview = integrator

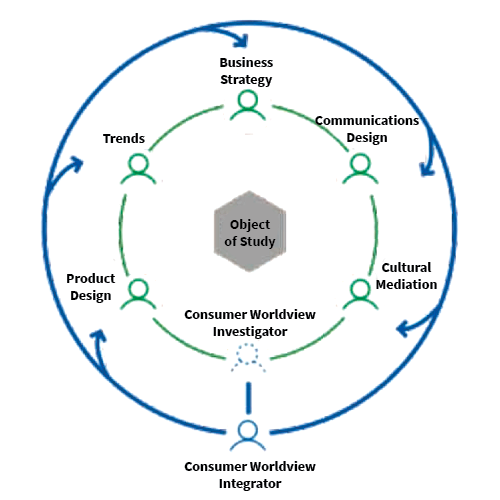

The composition of the team is a critical design problem in its own right. We did not envision sending a series of lone ethnographers out to spend time with individual research subjects. We identified the core “lenses” needed to produce insight and then found people who could use those lenses and think in the ways required. There were typically six such lenses: Business Strategy, Communications Design, Product Design, Cultural Mediation, Consumer Worldview Understanding, and Trends. The driving idea was to turn a multi-disciplinary team into an ethnographic task force. Thus the term “ethnographer” became a confusing misnomer, and we avoided it.

We found ourselves using the term Consumer Worldview Investigator. The specific individual role of such an investigator was to draw upon theories of culture, cognition, and social order to identify key shared understandings, and to help determine their longevity. The role also drew heavily on cultural mediation to help understand, interpret, and prioritize peoples’ words and actions. (The cultural mediators primarily acted as simultaneous interpreters, recruited for their strong general understanding of Chinese culture and contemporary society, and their demonstrated ability to help naïve teams work effectively in the field.) As anthropologists have traditionally done, the Consumer Worldview Investigator worked closely with these mediators, tapping into their expertise to develop culturally appropriate observations that could lead to insights. Together they explored inner worlds—such as those around movement and styles of personal expression—whose contours were foreign to American and European team members.

We composed small field teams out of the six lenses, so that team members could gain exposure to a variety of viewpoints and regional settings. The basic field unit was a three-person team: a Consumer Worldview Investigator, a cultural mediator, and a designer or strategist. Some team members had dual training which let them switch spectacles.

Given how critical consumer relevance is at every juncture, significant pressure arose to extend a consumer worldview focus into other disciplinary spaces (business strategy, communications design, product design, and trends). And these lenses began to refract one another, casting a shifting light across the emerging opportunities taking shape.

Instances of such refraction were innumerable. There was a competitive space for the brand (strategy) around altruism/we-thinking/community: what could that really mean (consumer worldview)? What did altruism in sport feel like, look like, and sound like to kids in different towns and cities (trends, communications design)? What were its key principles, and its colors and textures (industrial design)? How much variation was there in its expression (anyone)? Which of the variations was closest to what Li-Ning could authentically offer? Connecting to young women seemed an obvious business opportunity (strategy), but what were women’s aspirations (trends, consumer worldview)? Style was one thing, but sport for life was a very recent concept (trends). Were young women as ready to express themselves through sport as the young men seemed to be? And so on. All questions framed by other lenses intersected with each other repeatedly and in unexpected ways.

In this generative environment, the Consumer Worldview Investigator—or “ethnographer-ethnographer” for those who cannot live without the term—came to play two roles. One was consumer worldview exploration; the other, exploratory integration. Worldview specialists interviewed designers to understand what struck them as significant. “I’d see something from a design perspective,” said an industrial designer, “and then [the worldview person] would get me to say what I saw.” Moments after a hang-out, intercept or immersive “day in-the-life” consumer visit, the designers, strategists, and worldview people would speak into a camera together, riffing off what each other had seen and creating terse video syntheses on the fly. The worldview specialists then analyzed these for additional clues on how to synthesize and help generate insight.

FIGURE 1. A HYPER-SKILLED ETHNOGRAPHIC TEAM. The Consumer Worldview Investigator insures consumer relevance across multiple perspectives.

For despite whatever anyone else brought to the table, the consumer worldview investigator was accountable to the requirement of consumer relevance. The task of generative integration typically fell to those most attuned to matters of human relevance, and best able to articulate them. (Note however that in its executive aspect the business strategist held authority for integration. The key design stories had to work across apparel, shoes, and gear, for instance, and it fell to the business strategist to make sure all those pieces ultimately fit together.) The above diagram illustrates the relationship of the Consumer Worldview Specialist to the hyper-skilled ethnographic team.

Intellectual resource management

Wasson noted in her study of collaboration between designers and researchers at E-Lab (2002:81) that “researchers were often intrigued by discoveries that were tangential to the client problem.” Often in anthropologically-minded consumer work, a high tolerance is exhibited for discrepancy between a researcher’s perception of the value of his or her observations, and the client’s. That discrepancy can be costly, not just in terms of time and budget (which are considerable), but in the creative energy and momentum of the interdisciplinary team. Wandering afield on an intuition of rich discovery is critical: a prerequisite to the understanding and insight which are the creative engines of research. Yet the collaborative innovation team must have confidence that such exploration will be relevant—if not frequently, then in stunningly surprising ways.

Accordingly, there is an emphasis on frequently building out possible answers, or in “prototyping” possible results (to use design-speak), so as to increase the likelihood that the phenomena uncovered will in fact prove useful rather than merely interesting. How broadly do we need to reach into adjacent realms to solve the problem? Weighing issues on the table, how rich must the contextual understanding be? Why? If we could go deep on a primary issue and spend just enough time on a more peripheral issue to see whether it bears fruit, creating a contingency plan in case the peripheral issue later proves critical, are we likely to have learned enough to find valid patterns? Team members apply such relevance criteria carefully, so as to not to close doors on potentially rich areas; they also do so persistently.

Endpoint upfront

Let us take things for a moment out of sequence. When a team first forms, the sensible thing is to solve the problem—immediately. Or at least form a hypothesis. The practice in the hard sciences of articulating hypotheses before conducting an experiment is rarely followed in ethnographic work, owing to the idea that its process is inductive rather than deductive. This is a great shame, as a hybrid approach usually works better for teams. Stating hypotheses clearly carries little risk as long as a team accepts that they are provisional and that the team’s job is to explore rather than test them, and to evaluate, update, or discard them at key checkpoints.

The advantages to this approach are immense, particularly for a collaborative team which must concentrate its efforts in time. Imagining at the outset what the answer might be clarifies the nature of the collective goal, revealing knowledge gaps and weak assumptions. It helps team members understand their likely contributions. And it establishes benchmarks for tracking future progress toward insights.

Hypothesis tracking was a deliberate component of the work for Li-Ning, utilizing helpful collaborative technologies, specifically a blog and a wiki. If the blog was the group’s communal memory, the wiki was its collective understanding. The research blog was intentionally designed to be an organically messy, creative jumble of ideas: a forum for teams to upload great photos, write up rich, meandering thoughts, comment on nightclubs, or shout-out (or vent) to another team member in a different city. It was a very loose, dynamic, daily project.

The wiki on the other hand, was the repository of key project hypotheses. It formed a collection of curated, effectively “proven” observations that helped us to systematically track and institutionalize our knowledge. Moderated by the business strategist in an executive role, it included regular updates to our hypotheses about the patterns in people’s behaviors, attitudes, and values. If something changed in the wiki but someone on the team disagreed with the new formulation, that disagreement had to be resolved for the team to move forward. This allowed us to effectively build on what was known using new probes and revisions to fieldwork protocols.

The hypothetical product line strategy we envisioned for Li-Ning in those early days bore little resemblance to what we eventually developed after months of research. But marking and memorializing that understanding prompted questions about the competitive landscape, perceptions of the Li-Ning brand, Chinese political history, changes in the history of sport, and a prodigious (but not infinite) set of other issues. The team could see we had a lot to learn if we were to develop a product strategy past the crude skeleton from which we began.

Insight revisited

As previously stated, an insight is a distilled representation of the relevant knowledge needed to solve a problem or make something happen, and a precursor to potential innovation. But what form does it take? Images and diagrams increase its value and ultimately embody it, but its textual form is generally a strong, simple, statement that is rich with multiple potential meanings. Such polyvalence is critical because it lies at an inter-disciplinary confluence. All must be able to understand, interpret, and draw inspiration from it.

Consider for a moment the following statement from the work with Li Ning.

“For Chinese youth today, sport is not about winning, but about how to play.”

This formula constitutes an insight in the technical sense because it caps a tight convergence among the six critical perspectives(or “lenses,” described on page 7). From Chinese cultural and consumer perspectives, sport was not about winning. On public courts the shouts of “good shot” and “try that again” told us sport in this scene was not about “ball hogging” and “hot-dogging” (as in the US and many other places) but about building relationships and enriching experience. The phrase “how to play” signified that what mattered for kids in urban China in 2007 was growth, both personal and collective. It also has legs from a product design perspective. “How to play” makes for a product-use mindset, and for positing usage goals, which can drive ideas for making the thing: “Do I need to be strong, or quick, or controlled for this game?”

A trends perspective suggests that the theme of collective and personal enrichment may be temporary. It holds for Chinese youth in of 2007, and certainly for Gen Y, probably into their next decade. But its experimental expressions could subside in a few years and Li-Ning needed to allow for that.

Finally, recalling our quick treatment of the competitive landscape earlier, the idea that sport is “not about winning” does much from both strategy and communications perspectives. Nike isn’t doing this; nor is Adidas; nor is Puma, etc. Nike’s brand, for instance, is very definitely about winning. “You don’t win silver; you lose gold,” went its ad campaign for the ‘96 Olympics. Adidas is about geek-tech performance. Puma is about lifestyle. But so far, nobody has been selling a versatile “how to play,” implying potential for unique positioning. Such convergence around relevance and potential market significance is a primary distinguisher between true insights and simple observations.

IMPLICATIONS

We conclude with a set of implications for the work ahead. Reflecting on successful collaborations, Maria Bezaitis of Intel’s People and Practices Research Group reminds us that, “Great stories didn’t emerge from brilliant individuals… they were borne from practice.” (Bezaitis 2009:156-7) At the same time, there’s a training problem. “Practice is personal,” she observes. “To ask young social science PhDs fresh out of world-class graduate programs and post-docs…to stop working in the way they are used to is arrogant and even disrespectful.” (2009:158)

No doubt this is true for many. But other possibilities exist. For ethnographers committed to theory but wishing to work in a corporate context, new modes of practice are necessary. It is perhaps no affront to ask people to find new ways to work if they grow in the process, and if like so many anthropologists receiving on-the-job training in industry, they understand anew what they can achieve with ethnography (or might not achieve, as they set anthropological theories against other explanatory and interpretative ones to see which prevail).

Unlike medicine, engineering, and other hard sciences where concrete applications justify their existence, strong anthropology/ethnography (or ”A/E“– a useful contraction from Baba [2005]) is with some notable exceptions still fundamentally bred to remain confined to academia. The academies nurture an ethic, worldview, and work style that have tremendous potential value. But for ethnographers who will eventually choose to work in a corporate context, it is important to understand that academia’s approach is only one side of the overall practice. As Wilner remarks, the identity of the anthropologist tends to be “an intellectual one, privileging academic inquiry as an end unto itself.” (Wilner 2008: 294) More generally, the academic “habitus” in which most theory-driven anthropology continues to be learned and practiced (Bourdieu 1984) exerts a continuous pull on corporate ethnography in ways that are both constructive and destructive.

The constructive influences of the academic approach are amply evident, including enrichment of theory and experimentation in pursuit of knowledge. Destructive influences emerge when considering something like collaborative practice. Intended or not, academic environments tend to promote isolation of individual practitioners, and atomization of their work within specialized theoretical contexts. Consider for instance the profound statement made about the nature of anthropological practice by the fact that grants and fellowships for graduate fieldwork normally go to individual practitioners, not groups. Work is understood on a timeline derived from university calendars and grant schedules rather than project outcomes. Rewards depend more on continuity with intellectual ancestors than demonstrations of empirical success. The type of knowledge that counts as relevant places paradigm shifts and critiques of existing traditions over relevance to solving social or market problems.

A/E can build collaborative work practice back into theory-driven academic programs, creating an appetite for hyper-skilling among the best theoretical minds. But to do so it must look to other fields for appropriate models and inspiration. Design programs at research-aware institutions such as the Illinois Institute of Technology, Carnegie Mellon, Savannah College of Art and Design and Rhode Island School of Design are ahead of anthropology programs in the US in their emphasis on collaborative practice. But even industries without a strong connection with innovation practice—or perhaps most especially these industries—have much to teach current and future generations of ethnographers.

Wherever an expertise must enhance and empower allied perspectives, it will face analogous challenges. These include embedded information management (corporate librarianship) and case management. Consider for a moment the similarly challenging role of “hospitalists,” who are physicians specializing in the full spectrum of inpatient care at hospitals. Their charter is to decrease costs without reducing quality of care in a high-stakes, immersive, totally integrative practice (Wachter and Goldman 1996, 2002). They must coordinate their activities with those of a number of specialists and insure that their orders do not duplicate efforts by those specialists (read “research protocols”), while taking care not to overlook any diagnostic procedures or charting information that may have a bearing on success (read: historical, cultural, marketing, strategic perspectives). They then offer solutions (read: business recommendations) that cannot create any adverse events or toxic drug interactions (i.e., brand or business strategy conflicts, or implementation problems).

Ethnography’s dō (loosely translated as “way of doing”) is holism: connecting disparate socio-cultural data and seeing greater meaningful patterns. Turning its gaze to business perspectives and business practice, it finds new patterns there, too. Hyper-skilling creates relevance and establishes new frontiers for the practice by exploring the sight lines connecting consumer understanding to other perspectives for innovation. In this way, it can reach past merely representing current worldviews to map these representations across the diverse perspectives of the businesses on whose success it depends.

Will Reese, Director of Research at Ziba is a PhD cultural anthropologist and an expert on human cognition, motivation and behavior. He drives new methods for research and mines the company’s intellectual capital on projects having a critical consumer insights and trends focus.

Wibke Fleischer, Senior Trends Specialist at Ziba reveals drivers of change that shape emerging ideas and lifestyles. Formerly a senior consultant for Trendbuero (Hamburg), Wibke is an industrial designer whose forecasting work has helped numerous companies to design appropriately for the future.

Hideshi Hamaguchi, Director of Strategy at Ziba is a concept creator, business strategist, and decision management guru. His strategic insights have led to numerous awards, as well as path-breaking products, such as the first USB flash drive for IBM with Ziba, and the technology for digital rights management through flash memory cards.

REFERENCES

Baba, Marietta

2005 To the End of Theory-Practice ‘Apartheid’: Encountering the World. EPIC Conference Proceedings.

Bezaitis, Maria

2009 Practice, Products and the Future of Ethnographic Work. EPIC Conference Proceedings.

Bourdieu, Pierre

1984 Homo Academicus. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Byrne, Byran, and Sands, Ed

2002 Designing Collaborative Corporate Cultures. In Creating Breakthrough Ideas, Byrne and Squires, eds. Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

Dawson, Mark

2002 Anthropology and Industrial Design: A Voice from the Front Lines. In Creating Breakthrough Ideas, Byrne and Squires, eds. Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

Depaula, Rogerio, Thomas, Suzanne L. and Lang, Xueming

2009 Taking the Driver’s Seat: Sustaining Critical Enquiry While Becoming a Legitimate Corporate Decision-Maker. EPIC Conference Proceedings.

Lombardi, Gerald

2009 The De-Skilling of Ethnographic Labor: Signs of an Emerging Predicament. EPIC Conference Proceedings.

Sacher, Heiko

2002 Semiotics as Common Ground: Connecting the Cultures of Analysis and Creation. In Creating Breakthrough Ideas, Byrne and Squires, eds. Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

Sherry, John W.

2007 The Cackle of Communities and the Managed Muteness of the Market. EPIC Conference Proceedings.

Wachter, Robert M., and Goldman, Lee

2002 The Hospitalist Movement 5 Years Later. Journal of the American Medical Association 287:487-494.

Wachter Robert M., and Goldman, Lee

1996 The Emerging Role of ‘Hospitalists’ in the American Health Care System. New England Journal of Medicine 335 (7): 514–7.

Wasson, Christina

2002 Collaborative Work: Integrating the Roles of Ethnographers and Designers. In Creating Breakthrough Ideas, Byrne and Squires, eds. Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

Wilner, Sarah J.S.

2008 Strangers or Kin? Exploring Marketing’s Relationship to Design Ethnography and New Product Development. EPIC Conference Proceedings.

Ziba Authenticity is Now: A Working Definition of the Fluid State of Being as it Applies to Business and Design. Published by Ziba.

Web resources

David Altschul

http://www.characterweb.com/characterweblog/2009/12/the-road-to-hell-is-paved.html, accessed 1 July 2010.