This case study argues that all research should be trauma-informed research. It asserts that because researchers cannot anticipate everything about research participants’ needs, histories, and context, taking an approach that assumes all participants are more likely than not to have experienced trauma should be the paradigm for researchers. Even before receiving formal training in trauma-informed research, incorporating methodologies from trauma-informed research can make all researchers more human-centered. From March–April 2020, researchers from Airbnb conducted research to help launch a program that provided free or discounted accommodations to COVID-19 frontline workers: Frontline Stays. The researchers needed to conduct research with both frontline workers and Airbnb hosts who were temporarily opening their homes to them. Some of the researchers had received formal training in trauma-informed research. Others did not have the training, but recognized that it was important to understand and apply some of the principles for the Frontline Stays work. For this research project, it was clear why the researchers should assume that research participants had a history of trauma or were currently experiencing trauma. But COVID-19 was also a catalyst for the researchers to rethink what their baseline approach to conducting research should be. The case study outlines the trauma-informed methodologies the researchers used and discusses how this impacted their research methods and approach with stakeholders.

Keywords: trauma, public health, community-based housing, housing, social impact

INTRODUCTION

In March 2020, it was clear that COVID-19 was becoming a global pandemic. During these early months of the pandemic, many healthcare professionals and other COVID-19 responders needed to self-isolate. Others were traveling to hot spots and were at risk of being without shelter; many people were hesitant to rent or sublet to them. Responders who stayed in place worried about exposing their families and communities to the virus, especially due to the lack of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Responders also faced immense pressure as they provided for patients and worked longer and more frequent shifts.

THE RESEARCH NEED

Since 2012, Airbnb has partnered with Hosts, nonprofit organizations, emergency management agencies and governments to provide stays to people around the world in times of crisis. The program was formalized as Open Homes in 2017, and focuses on providing temporary housing to refugees and asylum seekers and people displaced by disasters or other crises around the world. (As of December 2020, the work sits under Airbnb.org, a nonprofit organization that connects people in crisis to safe, comfortable places to stay.)

When the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic became clear, multiple teams at Airbnb were keen to help. Teams saw an opportunity to adapt the existing program and technology tools from Open Homes to help temporarily house frontline workers including healthcare professionals, firefighters, and others. As the teams were adapting and expanding the program and product to accommodate frontline workers, there were many open questions to answer: How long would responders need accommodations for? What specific needs did frontline responders have? How easy or difficult was it for them to find and book temporary housing through Open Homes? Airbnb Hosts were being asked to provide temporary housing at the onset of the pandemic: How many Airbnb hosts would be interested in temporarily housing responders? What information would they need to have in order to participate in the Frontline Stays program? Would hosts need additional support or resources to feel comfortable hosting responders?

Researchers worked closely with Product, Engineering, and Operations teams to help adapt the Open Homes program so it could provide free or discounted accommodations to frontline workers: Frontline Stays. The researchers needed to conduct research with both frontline responders and Airbnb Hosts. In the first weeks of Frontline Stays, the research goal was to understand how to make it as easy as possible for frontline workers to find and book temporary housing. As the Design and Product teams iterated on Frontline Stays, an ongoing research goal was to identify barriers to finding accommodations on an ongoing basis. On the host side, the early research goals were to understand any hesitations around hosting frontline responders and what information they would need to assuage these concerns. As the program matured, the host-side research goals were to understand challenges hosts were facing while hosting responders, and whether they were experiencing any usability issues.

Understanding user needs was the usual work of researchers at technology companies, but conducting research during this unprecedented time brought complications the researchers needed to address. The context of the COVID-19 pandemic had particular relevance for some of their research participants: There was already news coverage about the level of trauma that medical professionals were experiencing as they faced overwhelming numbers of patients in hospitals, inadequate PPE, and grueling hours. This was the group of people Frontline Stays was being set up to help. And trauma wasn’t limited to responders: In early conversations, it was immediately clear that hosts were grappling with uncertainty about how to stay safe, worries about the future, and income loss. Many of these hosts were willing or even excited to give back, but they were also trying to make complex decisions during an overwhelming and difficult time.

Taking a trauma-informed research approach means researchers design their research approach and conduct interviews with research participants in a way that assumes a history of trauma. The need for trauma-informed methodologies was immediately clear given the individual trauma COVID-19 frontline workers were experiencing through their work and the mass trauma people across the world were experiencing as the pandemic disrupted their lives. Some researchers on the team had previously received training in trauma-informed care (“TIC”) from institutions like the San Francisco Department of Public Health. Other researchers on the team hadn’t been trained, but they needed to quickly learn and adopt some of the principles and methodologies to be able to conduct research for Frontline Stays.

They needed to adapt their approach while also working quickly to help meet the need for temporary housing. As the Frontline Stays teams tried to reach more frontline workers and onboard more people to provide temporary housing, they were seeking daily or weekly insights on what changes to make. The researchers needed to both take special care to protect their participants’ safety and ensure Product, Operations, and Design teams were receiving steady information about what changes they needed to make.

ADOPTING TRAUMA-INFORMED RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES TO CREATE A MORE HUMAN-CENTERED APPROACH

The researchers who had been trained in trauma-informed care worked with other Airbnb researchers, Design team, Product team, and Operations leaders to ensure all employees working on Frontline Stays were versed in the principles of trauma-informed care. They focused on socializing five of the trauma-informed principles from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). SAMHSA is a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and runs the National Center for Trauma-Informed Care. The principles are outlined below, and how they impacted research methodologies is discussed afterward.

Table 1. Trauma-Informed Principles

| Trauma-Informed Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Safety | Prioritize and protect the psychological well-being of people in your care |

| Trustworthiness & Transparency | Provide full and accurate information about what’s happening and what’s happening next |

| Empowerment, Choice, and Voice | Give people agency and help them feel in control of what and how much information to share |

| Collaboration & Mutuality | Create partnerships with collaboration or shared decision-making |

| Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues | Recognize that trauma disproportionately affects those who are already vulnerable |

Adapted from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [1]

ADAPTING METHODS TO ANTICIPATE AND ACCOMMODATE THE UNKNOWN

A trauma-informed research approach means both adjusting research methods and getting buy-in from stakeholders about the approach. The following sections discusses how the research approach differed compared to a non-trauma informed approach and the impact of convincing stakeholders on other teams that this approach was important.

The standard UX Research study

When conducting research in a business context, the team optimizes for business impact. The process unfolds as follows:

- Getting buy-in: Researchers align with stakeholders to ensure there is a research need and that stakeholders will be invested in acting on the research.

- Scoping: Researchers work with stakeholders to understand the team’s business goals and translate them into a rigorous research plan.

- Recruitment: Identify and recruit a robust and representative sample.

- Fieldwork: Conduct systematic fieldwork (e.g., interviews with a strict discussion guide to stay on track and minimize bias).

- Share-out and Impact: Work with stakeholders to translate learnings into action.

The end-to-end process is typically weeks or months long. For Frontline Stays, the process had to span a few days because of the urgency to house frontline workers and the ever-shifting pandemic conditions that were changing hosts’ and potential hosts’ attitudes and behaviors. The whole timeline of the research process was severely condensed and occurring simultaneously with product development. The researchers also needed to diverge from their standard practice within each phase.

1. Getting buy-in

Product teams were used to receiving direct feedback on designs and rigorous usability testing with a minimum number of participants. In order to protect the psychological wellbeing of participants under the Safety principle, the researchers were hesitant to recruit frontline workers and/or conduct prototype testing via video interviews. Requiring video and high-speed internet access for prototype testing would violate the principles of Choice, and Equity. The researchers knew their standard methods for remote interviews would need to be reconsidered. Although the need for adopting trauma-informed principles was abundantly clear to the researchers, some stakeholders had to get comfortable with the divergence from standard methods. Part of a trauma-informed approach is systems-level change, and the researchers needed to start that work.

Researchers and designers initially worked with stakeholders to get buy-in on the approach through an academic lens, sharing educational resources and literature to help them understand how trauma could be impacting the health of users (frontline responders as well as hosts). The researchers then supplemented the academic lens with a systems approach by working with Amelia Savage, Global Support Operations Manager for Open Homes (now Airbnb.org). Amelia’s team – a specialized customer service team – regularly interacts with users who may be experiencing trauma, and had developed a training program for trauma-informed communication. Researchers worked with leadership to ensure the entire team underwent the training and was well-versed in the impact of trauma.

To reinforce the point that they were more likely to be experiencing trauma than not, one researcher turned to a relational approach by sharing anonymized first-person accounts from first responders. She combed through qualitative entries from the Frontline Stays submission form to surface “Daily Responder Stories” to help stakeholders understand and empathize with responders’ experiences. Once stakeholders heard from the responders in their own words, they were able to understand the distress the responders were experiencing and the urgency of their booking requests. The need to change the team’s way of working sank in. The combination of academic resources, training, and first-person stories made them realize that the team needed to revise the scope, constraints, and methods to avoid burdening or re-traumatizing our users.

2. Scoping

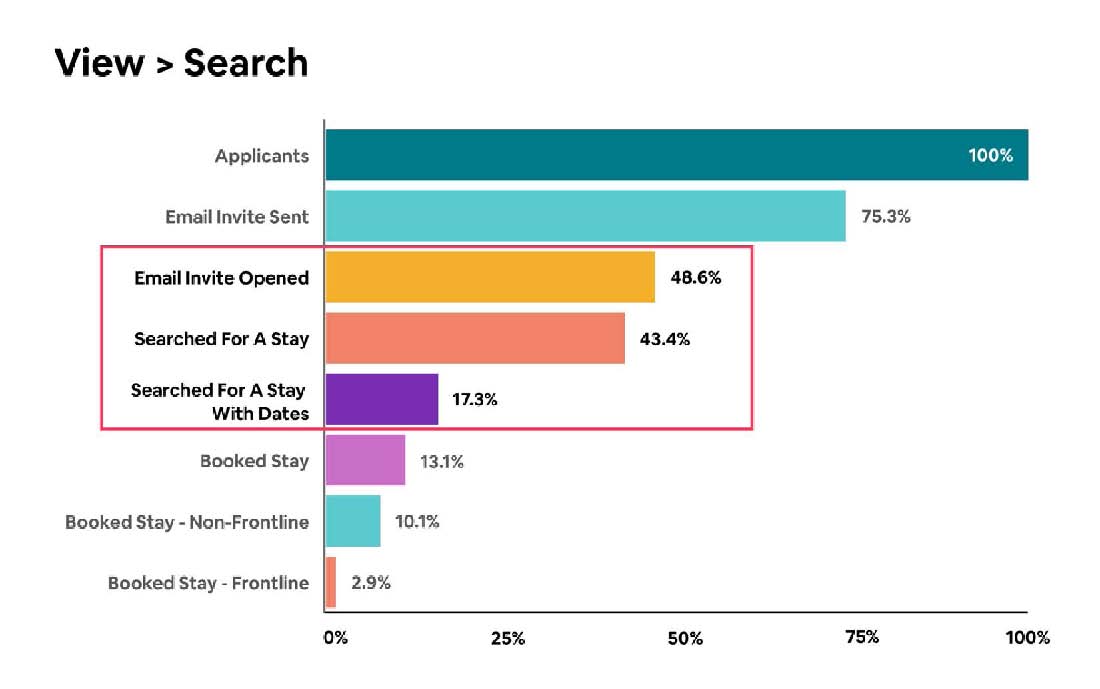

Normally, the researchers would have included in-depth interviews and usability testing as key parts of their research plan. One of the initial scoping constraints was finding data sources that didn’t involve direct communication with frontline workers, who were likely in the middle of an ongoing traumatic experience. These passive sources of data were mined to build a foundational base of knowledge and zero in to identify where direct feedback was needed. This way researchers could derive insight and guide the product and design teams, while minimizing responders’ time and energy. Although researchers are not typically responsible for detailed quantitative analysis of behavioral data, the team dove in and conducted a full anonymized analysis of the booking funnel, and identified areas where frontline responders were dropping off in the process of booking a home through Frontline Stays.

Figure 1. Funnel analysis chart for the Frontline Stays booking funnel. It shows that many responders searched for accommodations without adding dates.

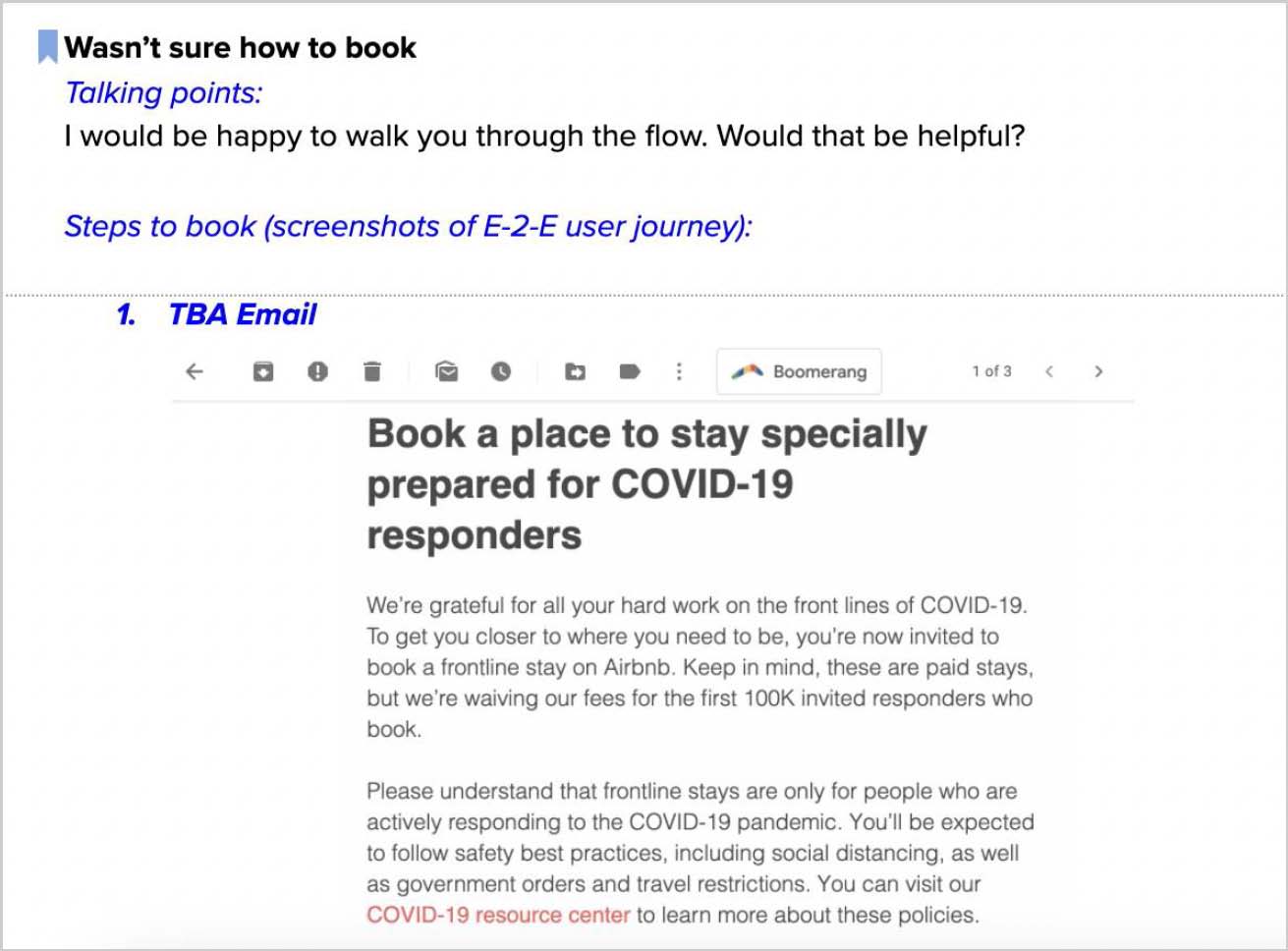

The funnel analysis showed that many responders were searching for accommodations without adding dates, which meant many of the search results were not available during their desired dates. These responders never returned to the search process. Under normal circumstances, the researcher would have recruited participants from this segment for interviews to understand their reason for drop-off. However, in order to adhere to the principle of safety, the researcher was forced to exhaust all other methods prior to engaging frontline workers directly. She dug deeper into the behavioral data. Further anonymized analysis showed that many of these responders were new to Airbnb and potentially unfamiliar with the booking process.

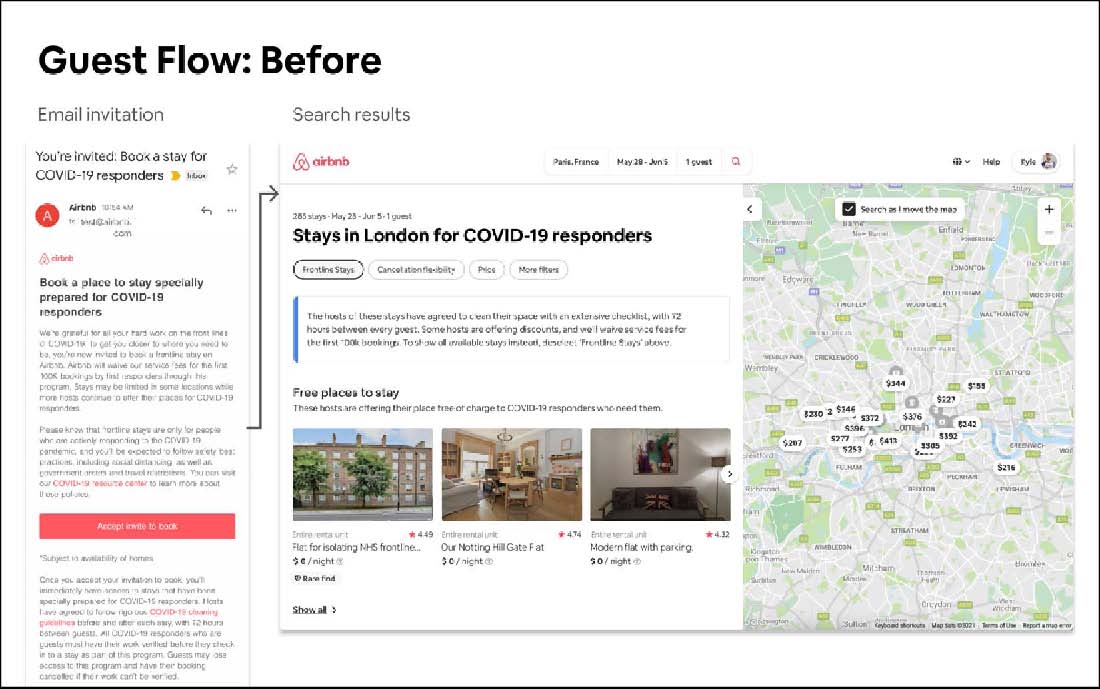

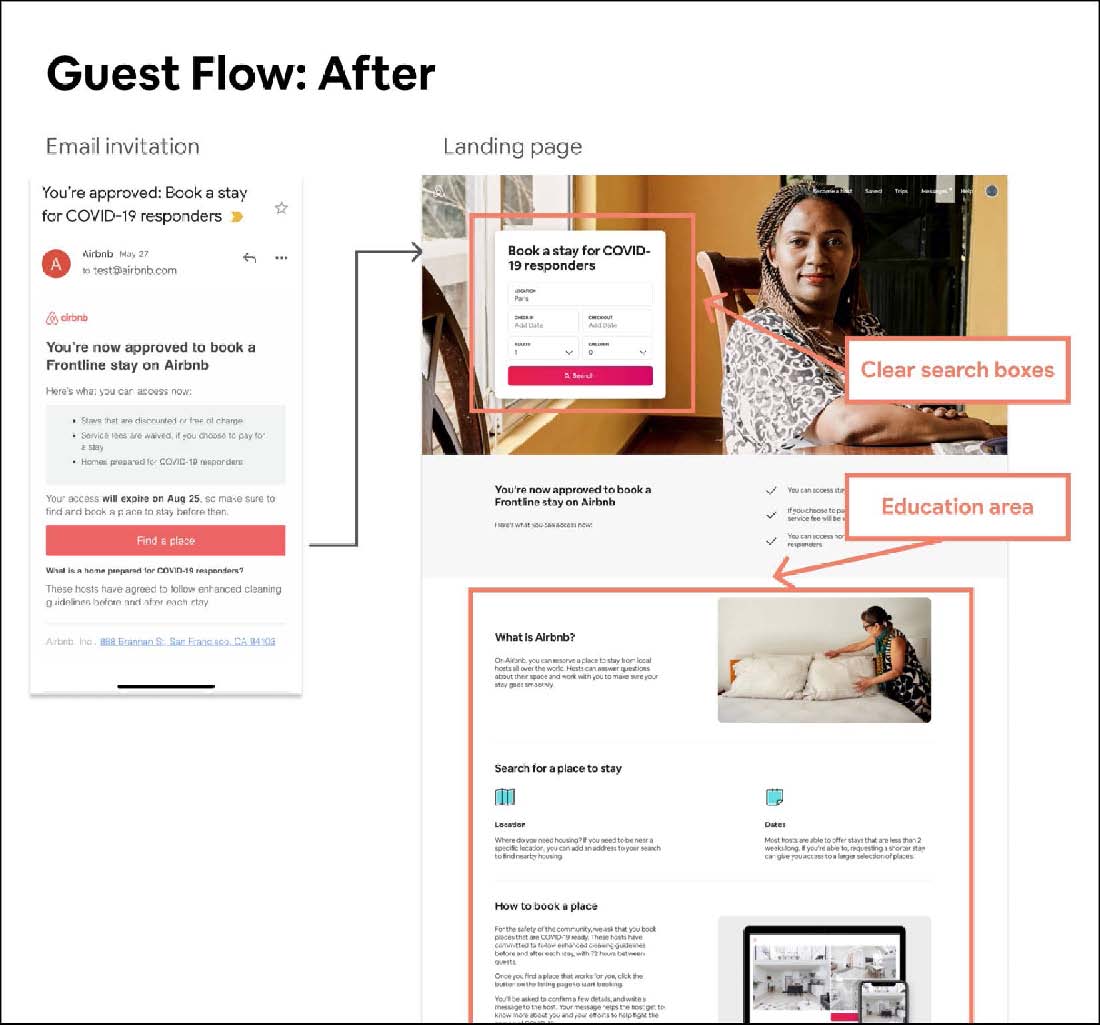

The booking flow at the time was designed to minimize steps between applying to the program and access to accommodations. However, in an effort to make the flow as quick as possible, the Design team had missed a crucial step: onboarding for new users. Additional interviews were not needed to determine the next steps: design an onboarding flow with education on how to use Airbnb. Looking at this from a trauma-informed lens meant the research team could discuss the potential magnitude of the issue: trauma impacts how easy it is to make decisions, which increased the importance of updating the user experience related to decision-making. Based on this analysis, the Design and Product teams revamped the flow to reduce cognitive load and make it more obvious that entering dates was part of the search process:

Figure 2. The original email invitation and search results page frontline workers saw through Frontline Stays. In this booking flow, many frontline workers missed adding dates to their search.

Figure 3. The updated email invitation and search results page. The revised booking flow included new user education and made it more clear how to enter dates when searching.

Adjusting the balance of research methods because of the trauma-informed lens forced the researcher to expand her methodological toolkit, and resulted in quicker and less resource-intensive insights.

3. Recruitment

The research team was used to having a large pool of hosts and guests to recruit from, with a robust recruitment process. However, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the research operations team paused all recruitment to avoid bombarding people with email during a time when they might be undergoing trauma.

The exception was for limited Frontline Stays research. For safety reasons, all interviews with potential Frontline Stays Hosts were conducted virtually. Normally, the research team’s screener ensured remote interview participants had a long list of criteria: internet access that could support a 60-90 minute video call, willingness and ability to take the interview from a desktop or laptop computer (no tablets or phones), attestation that they could take the interview from a quiet and non-distracting space, and so on.

Limiting the pool of participants in this way already introduces bias: it is a privilege to have access to all of the criteria listed above. Potential research participants who meet all of these criteria and have time during the workday to participate in research are a nonrepresentative group. This was especially true at the beginning of the pandemic. People were newly working from home, trying to manage childcare and work at the same time, experiencing job losses, moving out of apartments, and more.

Recognizing this, the team adjusted their recruiting criteria to make sure they would reach potential Frontline Stays Hosts who represented a diverse array of attitudes, backgrounds, and current context. This decision aligned with the equity principle in a trauma-informed research approach, which requires trying to recognize historical trauma, move past biases, and create culturally responsive research and design. From a recruiting perspective, this means not inadvertently excluding groups of people from research just because they are more difficult to recruit. Groups who are more difficult to recruit are frequently part of groups already disproportionately affected by trauma. Leaving them out of research studies at technology companies means teams run the risk of inadvertently retraumatizing them or othering them when they use the product. But making the additional effort to recruit difficult-to-reach groups and get a diverse set of perspectives also makes for better research.

Updating the screener was one part of this effort for Frontline Stays. Another key component was offering a wide set of potential interview times to include participants who weren’t available from 9am–5pm. The standard practice at technology companies is to conduct interviews between 8am and 6pm, unless the research primarily focuses on a group who is not available during that time. The researchers offered interview times outside of the typical window to ensure they could recruit participants who were unavailable during the day – people juggling at-home work and childcare, employees at fast food restaurants who only get 15-minute breaks, etc. To protect their mental health, the researchers temporarily shifted their working hours or ended future work days early after studies that included interviews conducted before or after normal working hours. The team combined this with their standard practice of using optional questions about gender, age, and race in the screener to recruit a diverse set of perspectives.

The researcher interviewed potential hosts who didn’t own personal computers and did the video interview via smartphone, who had to pause the interviews to help their children with school, and who had to join via phone because their home’s bandwidth could consistently only support one video call at a time. The varied interview settings drove home the extent to which many potential hosts were trying to make a big decision – whether to offer free or discounted temporary housing to people who might have been exposed to COVID-19 – while already dealing with a higher level of stress and uncertainty. Choosing to recruit participants who were more difficult to schedule and adjusting the recruiting criteria helped the researchers to paint a more accurate picture of the various potential host experiences, hesitations, attitudes. Being able to talk about how varied the hosts’ contexts were also helped the researchers remind the Product and Design teams that hosts were not going through the sign-up flow in a vacuum. The Operations team continuously updated the Help Center to craft and rewrite the content they knew hosts needed based on the research, such as information about the program policies designed to help keep Hosts safe. The Design and Product teams updated the host sign-up flows to improve the clarity of the in-product education in the sign-up flow and tools such as calendar management.

Using trauma-informed principles for recruiting meant balancing equity with rigor. The need for trauma-informed recruiting was clear, but the key tenet of trauma-informed research is that researchers should act assuming it’s more likely than not a participant has a history of trauma: it’s impossible to know every participant’s full history. All research should be trauma-informed research, and all recruiting should consider equity.

4. Fieldwork

A. Trauma-informed interviews

For interviews, the researchers adopted practices from the FRAMES model of motivational interviewing. Work in the past decade has shown the applicability of motivational interviewing skills in a trauma-informed framework.[2]

Table 2. Trauma-Informed Interview Framework

| “FRAMES” | Description |

|---|---|

| Feedback | Provide feedback about the context and reason you are requesting information |

| Responsibility | Encourage the person to take charge of their participation |

| Advice | Provide direction in a gentle, non-directive manner |

| Menu of options | Provide a range of options when possible |

| Empathy | Express empathy both verbally and non-verbally to make it clear that you care about the person’s well-being |

| Self-efficacy | Provide positive reinforcement by highlighting their courage and willingness to participate in interviews and share information |

Adapted from Hester and Miller, 1995.[3]

B. Breaking habits

The researchers also had to break habits. This included no longer using common questions and responses that come naturally when other people are sharing difficult stories or when one wants to express empathy. What seemed innocuous could potentially re-traumatize. The Research and Operations teammates who had received trauma-informed training put together a list of questions to avoid, as well as things to say instead. To name a few:

Table 3. Common Phrases to Avoid, And Suggested Replacements

| Phrases To Avoid | Phrases To Use Instead |

|---|---|

| “How are you?” This common phrase to build rapport at the beginning of interviews has the potential to trigger people going through active trauma. For example, asking a doctor who’s just lost a patient to COVID-19 how they’re doing may remind them that they’re not doing well, remind them how difficult it was to lose the patient. More generally, it might be the anniversary of a traumatic event. |

“Is this a good time?” This started the conversation, and also gave participants choice in whether they still wanted to participate. |

| “I understand how you feel.” First, the research team didn’t. Second, it potentially minimized the research participant’s experience. And finally, it could potentially close off an avenue of conversation. Participants who might have more to say might not share their next thought after being told, “I know how you feel.” If the listener says they already understand, why explain further? In the same way researchers are trained to ask open-ended questions and indicate with body language that they are listening, the trauma-informed approach adds an extra layer of ways to avoid accidentally closing off the conversation. |

“Thank you for sharing that.” The phrase affirmed that the researcher was listening and acknowledged that the information might have been difficult to share. It also reinforces that their sharing the story was a choice. This aligns with the trauma-informed principle of “Empowerment, Choice, and Voice,” ensuring participants know they have control over how much and what they share. |

| “I’ve heard a lot of people are experiencing…”: In a time of commiseration and global fear of the unknown, it was particularly tempting for the researchers to use phrases that alluded to the larger world. This phrase and others had the potential to minimize the research participant’s experience by suggesting it was universal or unremarkable. The same is true for all research interviews. Again, trauma-informed research principles are applicable for all research precisely because the researcher cannot anticipate what trauma a given person might have experienced. | “I’m sorry that happened.”“That sounds really difficult.” Both phrases are relevant when the participant has shared something that was upsetting to them or emotional. Again, they avoid accidentally closing off part of the interview.They affirm that the researcher is listening and empathetic while also centering the response on the participant and their experience. |

A list of frequently-used questions and phrases to avoid as part of a trauma-informed research approach. The researchers had anyone who would be speaking to frontline workers or Hosts practice using the replacement phrases.

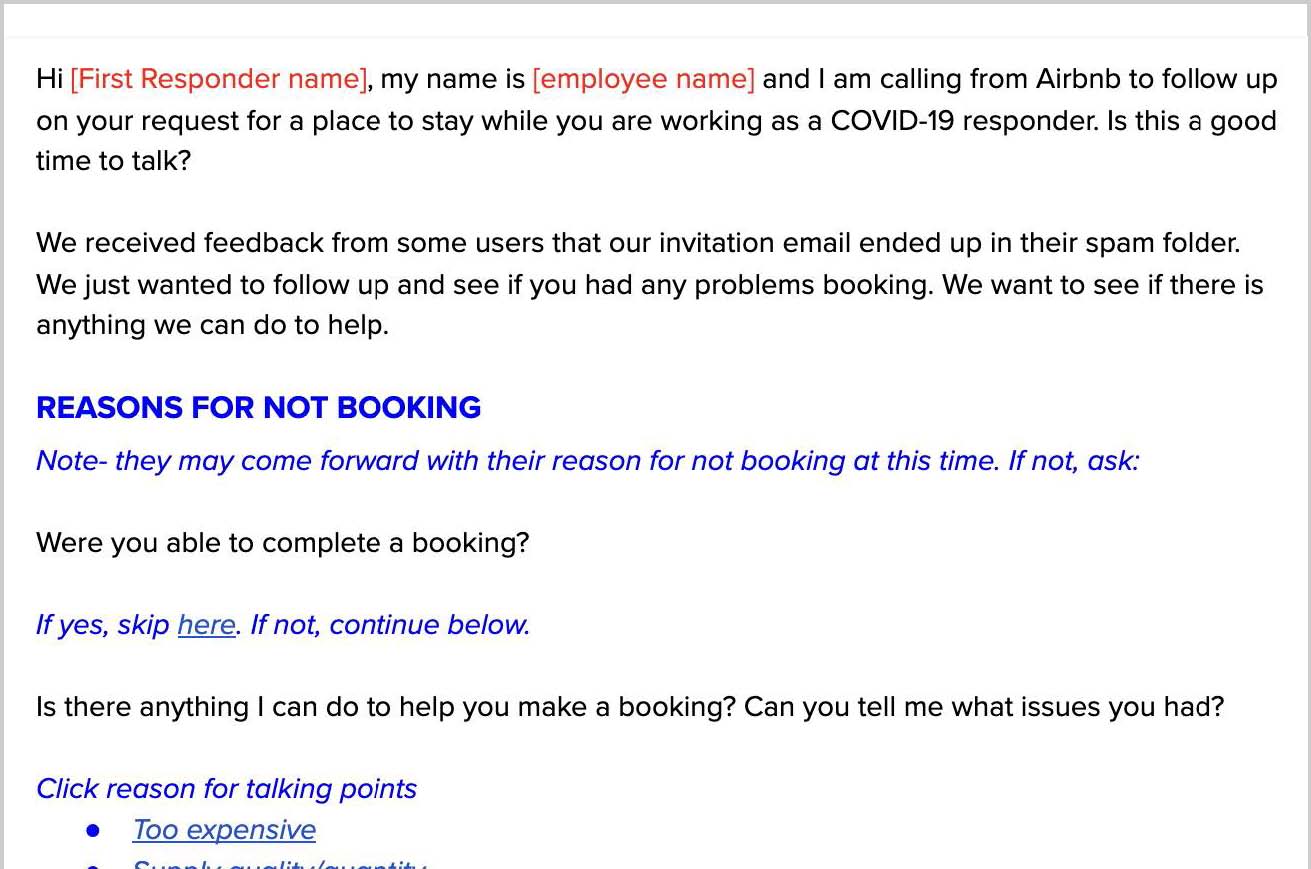

Researchers are already trained to avoid asking “Why?” since it can sound accusatory or like the participant has to justify their answer. Replacing these phrases is the next layer in more human-centered research because it also prevents accidentally closing the conversation or minimizing participants’ experiences. To break their habits using these phrases, the teams used and practiced a line-by-line script for interviews with frontline workers.

C. Providing in-session support

While conducting UX research in a standard business context, one way that researchers strive to reduce bias is by systematizing fieldwork (e.g., hour-long interviews, using a strict discussion guide, prototypes, etc.). The guide ensures that each participant receives the same set of questions, and the researcher’s choice of language or order of questions does not impact the responses. Most importantly, research sessions are strictly to gather information. Under no circumstances should the researcher solve user issues in-session, because that would bias the data collection. This ensures that the differences observed during the sessions are primarily due to participants’ attitudes, and not due to the researcher’s behavior. The guide also ensures that the researcher is able to stay on track to answer the most crucial business questions, and avoid topics that don’t pertain to business objectives.

Two of the key principles in the framework the team adopted to be more human-centered were Mutuality and Safety, meaning communication with frontline responders could not be pure information-gathering for the team, it should first and foremost address responder needs and issues. This meant breaking methodological rules about staying neutral in interviews: the researchers provided in-session support rather than just conducting in-depth interviews. In some interviews, the researchers onboarded first responders who were new to the Frontline Says platform over the phone, walking them through the booking process, and often live-searching for accommodations with them. One of the key manifestations of trauma is cognitive: The ability to process thoughts and make decisions.[4] It was clear that trying to learn a new system, narrow down accommodation options, and submit a request to a host—already a potentially difficult process—was an order of magnitude more difficult while experiencing trauma. Trying to solve responders’ issues while on the phone with them helped the researchers understand the urgency of the task at hand and empathize at a deeper level with how taxing the booking process was. As a result, the 15-minute interview format was formalized into a proactive outreach program to provide first responders live human support when booking accommodations.

Figure 4. The beginning of the script for 15-minute interviews. Everyone calling frontline workers practiced avoiding questions such as, “How are you?”

Figure 5. Outreach script. The 15-minute interviews evolved into a proactive outreach program for frontline workers, and callers sometimes helped frontline workers book accommodations while on the phone with them.

4. Share-out and Impact

As discussed earlier, one researcher offered “Daily Responder Stories” to help create systems-level buy-in for using trauma-informed methodologies. Under normal circumstances, the researcher would have waited until conducting multiple interviews and synthesizing results before conducting a formal share-out meeting with the core team. The team would have taken a few weeks to internalize the findings and take action. Instead, she gave Design, Product, and Operations leaders anonymized quotes from the submission form on a daily basis. The researcher had to balance engaging the teams and potentially having the group get anchored on early stories that might not be the most representative after deeper analysis. To try to mitigate this, she framed the daily updates as “stories” and thoroughly analyzed research as “insights” and “research findings.” She also avoided sharing stories that seemed like potential outliers – if something new or unusual came up in a responder story, she waited to see if it was part of an emerging theme before deciding whether to share it.

The researcher’s approach helped build buy-in for both trauma-informed methodologies such as leaning on funnel analysis for the exploratory research and later recommendations. Hearing directly from frontline workers allowed the team to feel more connected to the mission of the program and the people they were helping. It created an urgency and motivated the team to move much quicker and escalate upon hitting any blockers.

LESSONS

After two months, the researchers walked away with four key learnings about the importance of immediately adopting trauma-informed methodologies:

Don’t let the research brief become the enemy of finding answers. The phrase, “Plans are useless, planning is everything,” resonated strongly at the end of the research projects. Government regulations, knowledge about COVID-19, and the global economy were shifting on a daily basis. It was impossible to anticipate what the researchers, their team, or the world might know the next day or week. In a context that defied prediction, the focus became anticipation: having a framework to be ready for all the ways that research participants might show up to sessions, being ready to jump in if a frontline responder urgently needed help finding temporary housing, and making an extra effort to recruit a diverse pool of participants to build products that are better for everyone. Adopting trauma-informed methodologies was a key way to approach the fluidity that the moment required. It is specifically designed for scenarios researchers can’t predict: what any given research participant has gone through, what they’re going through, and what they’re bringing to a particular research session. This inability to predict is true of every research study – so all studies should have a trauma-informed lens.

Don’t let methodological purism get in the way of making sure research helps identify needs and potential ways to solve them. In interviews, frontline workers were often joining the call in the middle of back-to-back tasks. The pacing was frenetic. Frequently, a way to build trust in interviews is to spend time building rapport with participants, such as asking warm-up questions to show interest. For frontline responders, the way of building rapport in interviews was to demonstrate an understanding that their time was valuable and short. The researchers built this rapport by jumping more quickly to the meat of the conversation or providing in-session support. If the researchers had stuck to the usual playbook, they would have potentially re-traumatized research participants and gotten less information from the sessions.

Bring the whole team into the trauma-informed framework. The researchers and designers spent time not just incorporating trauma-informed principles into their work but also making sure the team understood why they were approaching their work that way. It also included explaining how a trauma-informed approach can produce rich insights and improve product outcomes while also protecting participants.

Researchers need to care for themselves so they can show up the next day. The researchers frequently referenced the list of people who were potentially going through trauma, with the reminder it included themselves. This had two sources: emotional duress from interviews with frontline workers and Hosts and living through the COVID-19 pandemic. An important part of showing up to do research the next day was finding ways to find a sense of calm, decompress, and look inward to recognize and respond to cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social signs of trauma. (As discussed in Osofsky, Putnam & Lederman, 2008 and Adams, Boscarino & Figley, 1995.)[5][6]

CONCLUSION: ALL RESEARCH SHOULD BE TRAUMA-INFORMED RESEARCH

The pandemic was a source of trauma around the world, and sparked wider conversations and media coverage about the impact of trauma. It made the issue more visible. But obviously, it is far from the only source of trauma. Researchers cannot know what trauma or traumas participants have faced. There are certain types of research where a researcher could predict a higher likelihood that participants have experienced recent trauma. But the point of trauma-informed research is precisely that prediction is imperfect. What is better is anticipation: assuming that an individual is more likely than not to have a history of trauma, and conducting research accordingly. Research is inherently about uncovering the unknown. A trauma-informed research approach gives researchers a framework to uncover and tell a story about the unknown while keeping their participants safe.

Trauma-informed research requires training, practice, and buy-in from multiple teams within an organization. But adopting some of the methodologies, such as avoiding potentially triggering phrases, is something all researchers can do immediately. This is to protect participants’ psychological safety, but it also means conducting better research. Adding the additional layer allows researchers to come closer to the goal of conducting truly human-centered research.

Meredith Hitchcock leads User Experience Research in service to Airbnb.org. She co-founded RideAlong, where she built software to help first responders more safely interact with people experiencing mental illness and divert them away from jail. She was a Safety & Justice design fellow at Code for America.

Sadhika Johnson is a mixed methods researcher and strategist, with experience in UX research & design, consumer insights, and brand strategy. While at Airbnb, Sadhika led foundational primary research and strategic thinking to help define new problem spaces and verticals, serving as a trusted partner to product leadership in defining the team strategy, vision, and roadmap. Prior to that, she helped establish the Consumer Insights team at Airbnb, conducting first party quantitative and qualitative research to inform marketing and product strategy.

NOTES

Acknowledgments – The authors would like to thank Emily Anne McDonald, Ph.D. (Senior Manager, Strategic Research and Evaluation, in service to Airbnb.org), Aashna Chand (Associate Counsel, in service to Airbnb.org), and Mattie Zazueta (Senior Communications Manager, Corporate & Policy) for their guidance and feedback in writing this case study. They want to acknowledge the effort of the large group of Airbnb and Open Homes (now Airbnb.org) teammates who came together quickly to launch the Frontline Stays program in 2020. They also wish to thank the first responders, Airbnb Hosts, and subject matter experts who generously shared their time, thoughts, and ideas with the team during an exceptionally difficult time.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884, Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014), https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf.

2. “Guiding as Practice: Motivational Interviewing and Trauma-Informed Work with Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence Motivational Interviewing and Intimate Partner Violence Workgroup,” Partner Abuse 1, no. 1 (2010): 92–104, https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.1.1.92.

3. Reid K Hester and William R. Miller, eds., Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1995).

4. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services (Rockville, MD, 2014), Chapter 3, Understanding the Impact of Trauma, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201.

5. Joy D. Osofsky, Frank W. Putnam and Judge Cindy Lederman, “How to Maintain Emotional Health When Working with Trauma,” Juvenile and Family Court Journal 59, no. 4 (2008): 91–102, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-6988.2008.00023.x.

6. Richard E. Adams, Joseph A. Boscarino, and Charles R. Figley, “Compassion Fatigue and Psychological Distress among Social Workers: A Validation Study,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 76, no. 1 (2006): 103–8, https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103.

REFERENCES CITED

Adams, Richard E., Joseph A. Boscarino, and Charles R. Figley. “Compassion Fatigue and Psychological Distress among Social Workers: A Validation Study.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 76, no. 1 (2006): 103–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4816. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201.

“Guiding as Practice: Motivational Interviewing and Trauma-Informed Work with Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence Motivational Interviewing and Intimate Partner Violence Workgroup.” Partner Abuse 1, no. 1 (2010): 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.1.1.92.

Hester, Reid K., and William R. Miller, eds. Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1995.

Osofsky, Joy D., Frank W. Putnam, and Judge Cindy Lederman. “How to Maintain Emotional Health When Working with Trauma.” Juvenile and Family Court Journal 59, no. 4 (2008): 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-6988.2008.00023.x.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf.