THE PROFIT-PURPOSE CONUNDRUM

Friction Ties the Knot

In recent years, the software development industry has portrayed itself as capable of harmonizing profit and social purpose (Corduneanu, 2022). Similarly, nonprofit organizations have started adopting characteristics from their for-profit counterparts, emphasizing profitability and sustainability (Maier, Meyer, and Steinbereithner, 2016). On the surface, it might appear that there is no inherent friction between these sectors, but a closer examination reveals a complex relationship.

The friction between profit and purpose for these institutions becomes evident when comparing their primary objectives. The software industry prioritizes efficiency to increase profit (Alptraum, 2017), while the nonprofit sector’s primary goal is social change (INCITE!, 2017).

SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT INDUSTRY VS. NONPROFIT SECTOR

Purpose, Ethos, Raison d’etre:

The divergent objectives between these sectors create significant differences in their organizational structures. Software companies favor hierarchical governance structures and functional capabilities to optimize product delivery (CodeRiders, 2022), while nonprofits, driven by collectivist beliefs, resist corporate-style hierarchy (Baines, 2010).

Operational processes and team compositions also vary. Software companies employ intricate production processes that rely on specialized teams for efficiency and profit maximization (Sypnopsys, 2023). Nonprofits, instead, operate within five functional areas: executive strategy, administration, fundraising, program delivery, and evaluation, which often focus on serving their communities.(Ensor, 2023).

At its core, the software industry’s ethos revolves around efficiency and profit, akin to the principles of the Ford production model (Gupta & Kohli, 2006). In contrast, nonprofits are dedicated to pursuing the ‘common good,’ employing efficiency, metrics, and sustainability to achieve meaningful societal change (Abramson, 2019). This case study delves into the inherent frictions that arise when a B2B for-profit software company provides services and solutions to the nonprofit sector. Moreover, it offers an in-depth exploration of my lived experience as a researcher of color, navigating these frictions and leveraging research to uncover points of resistance and collaboration between these seemingly disparate sectors.

SALESFORCE AND NONPROFIT FRICTIONS

Salesforce

Given that, I became a Lead Researcher at Salesforce. Salesforce primarily specializes in building Customer Relationship Management (CRM) solutions. These solutions assist organizations in managing interactions with existing and potential customers during sales (Mailchimp, 2023). Nevertheless, Salesforce has successfully extended the scope of CRM beyond the sales process, believing that customers can harness CRM to optimize any business process. Part of that scope expansion entailed developing targeted industry solutions, which led to the development of Salesforce Nonprofit Cloud, the team I eventually joined.

Nonprofit Cloud Team

Salesforce’s Nonprofit Cloud comprises a suite of products designed to assist nonprofit organizations in fundraising, marketing, measuring, and fulfilling their missions. The Nonprofit Cloud teams operate within Salesforce’s broader organizational structure, with dedicated scrum teams comprised of product managers, engineers, designers, researchers, and content writers responsible for delivering features tailored to the nonprofit industry’s needs.

As the lead researcher for the Cloud, my role involved coordinating research priorities between engineering, product management, and design scrum teams to help them improve software solutions.

Fundraising Solution and Assumptions

In the fall of 2022, the Nonprofit Cloud Fundraising team initiated work that sought to enhance fundraising efforts for Salesforce nonprofit customers. The team proposed two solutions:

The first proposed solution involved assisting nonprofit organizations in creating a donor dashboard, allowing them to showcase how individual contributions by their donors impacted the organization’s goals.

The second proposed solution sought to improve our customer’s internal organizational processes. While Salesforce’s Nonprofit Cloud suite offers a centralized platform for storing fundraising and program delivery data, numerous nonprofit organizations keep these data types separate due to their organizational structures. Fundraising teams typically have access to fundraising data, while program teams access program-related data.

Informed by client conversations, a Product Manager hypothesized that we could help our customers if we adjusted our Cloud’s data models to establish an automated pipeline connecting fundraising and program data. If this hypothesis were validated, fundraising employees would benefit from automated access to the program delivery information they need to craft convincing donation requests.

The product manager theorized that by keeping these data types separate nonprofit organizations were introducing inefficiencies that prevented fundraising departments from being as productive as possible. They speculated that these solutions would give our Cloud a competitive edge over similar products.

However, these proposed strategic solutions were based on institutional and industry knowledge rather than current actionable research. When the rest of the product team began exploring the solutions, it became clear we needed an even deeper understanding of the processes we were trying to improve for our customers. Confronted by these challenges, the team brought me on board to assess the validity of their solutions.

Research: Contextual Inquiry and Service Blueprinting as a Practice of Friction

The role of a researcher is to determine if ‘research validation’ is needed when a product team requests research to validate their hypothesis. A significant aspect of the researcher’s role is introducing friction into the team’s well-established processes by challenging assumptions and advocating for the customer’s experience.

Considering the proposed solutions, I wondered whether ‘validation’ research was necessary for our team. Was simply proving the validity or accuracy of the proposed ideas enough? Or would the team benefit from gathering a more profound understanding of our customer’s problems?

I suggested transitioning from a research validation exercise to a research discovery approach. I aimed to conduct research that could offer insights into our customers’ identities, the evolution of their governance and operational structures, their main objectives and tasks, and the tools they employ to achieve them. By gaining a deep understanding of our nonprofit customers’ internal operations, we could ensure the relevance of the proposed solutions.

Research Methods

I employed a series of ethnographic methodologies divided into three stages to answer these questions.

First, I initiated my research by extensively exploring organizational development and maturity concepts within nonprofit organizations. This involved a comprehensive review of over 20 secondary research sources. The literature review aimed to establish a common vocabulary and identify conceptual commonalities related to organizational maturity, structure, and governance, providing the team with a robust conceptual foundation.

Next, I coordinated and conducted eleven sixty-minute semi-structured interviews with Chief Executive Officers from different nonprofit organizations. The selection criteria for these eleven represented organizations were based on several factors, including employee size, projected revenue, and organizational mission. These criteria represented some variables I aimed to explore to understand our customers. This approach allowed me to assess whether those variables influenced the organizational structure, functional distribution, governance practices, and inter-departmental collaboration methods used to achieve their missions and goals.

Finally, I completed four service blueprint exercises involving department managers and day-to-day employees in the functional areas I had identified through the semi-structured interviews. Although I had identified five functional areas, I focused on the four most relevant to improving the team’s solutions: Fundraising, Programs, Volunteers, and Monitoring & Evaluation. These service blueprint exercises provided invaluable insights into how goal setting, functional structures, governance, and interdepartmental collaboration worked from the perspective of those engaged in the day-to-day tactical work of nonprofit organizations.

Insights

The research uncovered some powerful insights. Through the research process, I learned that the two strategy solutions proposed by the team couldn’t be implemented as we initially thought.

Insight 1

The team’s initial idea of helping Salesforce nonprofit customers create a donor dashboard that allowed them to showcase individual contributions by their donors couldn’t be implemented as originally envisioned. While speaking to nonprofit fundraising and program management professionals, I learned that the regulatory complexity of nonprofit accounting and funds distributions makes it challenging to keep track of individual giving and connect it to organizational impact. Donation intake and funds designation legislation forces nonprofit organizations to keep multiple complex accounting systems in place to comply with government regulations. Additionally, measuring and evaluating program participation impact is often time-consuming and complex. Both systems are operated by different departments or areas within an organization and tying them together cannot be solved by incorporating new features displayed on a donor portal; it would require organizational or legislative changes.

Insight 2

The team’s second idea, which considered adapting our Cloud’s data models to provide an automated data pipeline between fundraising and program data for our clients, presented equally significant problems. Through research, I discovered that implementing an internal data-sharing solution would raise considerable ethical concerns from our nonprofit customers’ perspectives. After consulting with nonprofit program managers, I found that employees in program delivery departments are hesitant to easily share information with fundraising employees because they are committed to protecting their constituents. They frequently expressed ethical concerns about the potential misuse and mischaracterization of their constituent’s impact data. Exploitation could occur if fundraisers recklessly used constituent data narratives to artificially generate sympathies to increase charitable donations. They believe fundraising departments could easily exploit the data, even if their intentions were well-meaning. As a result, they prefer to remain in control of how and when the program data is shared; an internally automated data pipeline would strip them of that control.

I was aware the implications of these findings would impact my team’s proposed solutions and, in general, our product development processes. I understood that the product team proposals’ core intent was to help our nonprofit customers be more efficient and transparent when requesting donations. They had theorized that eliminating those inefficiencies could improve our client’s processes. However, the research revealed that pursuing these product solution paths could compromise our customer’s success.

As a researcher, I understood my responsibility to convey these insights and encourage my team to adopt some research-based recommendations.

RESEARCHER TOOLS

Challenging Strongly Held Beliefs

Challenging the status quo in a large corporate organization can be daunting. I had to assess when and how to disclose the research findings, considering how the issues found with their proposed ideas might impact the team’s product development processes. A company’s maturity, research culture, and team’s internal dynamics will influence how introducing friction to those institutional processes is perceived.

Salesforce has always encouraged its employees to be bold truth-tellers. Nevertheless, “bold truth-telling” is not done in a contextual vacuum. Hence, as a researcher, I used a series of frameworks to ensure I delivered truthful insights while staying true to my identity and ethics.

Empowering Frameworks

Like any research project, I initiated the socialization process of my insights by conducting a preliminary consequence scan. I utilized Doteveryone’s (2019) and Salesforce’s Rob Katz’s (2020) consequence scanning frameworks, which consist of three key questions:

- Whatwerethesefeaturesintendedandunintendedconsequences?

- What are the positive consequences we want to focus on?

- What are the consequences we want to mitigate?

The research findings showed that the proposed solutions carried potential implementation challenges and ethical implications that could pose risks for our customers’ constituents. Consequence scanning allowed me to evaluate those research findings vis-à-vis my team’s proposed solutions, which, in turn, allowed me to build a case for my recommendations.

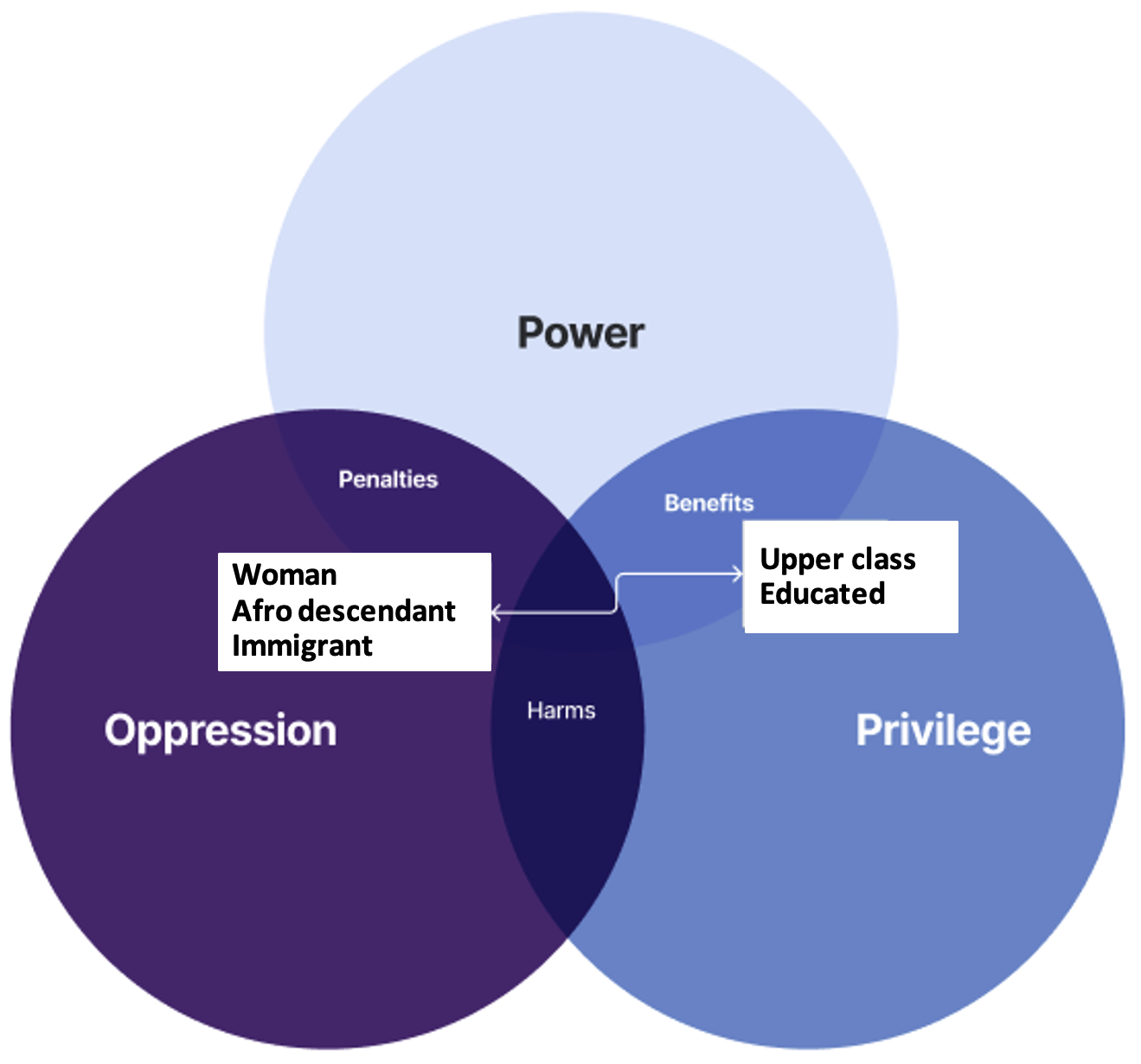

After I evaluated my findings for potential impact, I performed a power positionality assessment. I embarked on these positionality assessment efforts because scientific studies have shown that interpersonal, cultural, and institutional power dynamics affect how change and friction are received, perceived, and adopted (Boonstra & Bennebroek, 1998). These power dynamics matter even more if you are a woman with a racialized body. When it comes to delivering bad news, women of color experience the burden of being perceived as “angry,” which in the workplace often leads to worse performance evaluations and assessments of leadership capability (Motro, Evans, Ellis, Benson, 2022).

Given that a big part of research work is entangled with perception, women of color often have to contend with the possibility of bias seeping through. Being relatively new to my team, I always felt like straddling a fine line between delivering insights and risking alienation.

While Salesforce has made great strides in developing a more inclusive and multicultural workplace, like many other software development companies, it is still primarily a white male-dominated space. As a woman of color, understanding my positionality within this type of space is helpful, especially when I’m about to have a difficult conversation. To better understand my positionality, I built a positionality assessment diagram using Patricia Collins’s Matrix of Domination framework (Collins, 1990) and Kimberle Crenshaw’s work on Intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1993).

Understanding myself and my team within the Matrix of Domination allows me to explore my vulnerabilities and recognize my privileges in a corporate space. This knowledge clarifies power dynamics and empowers me to advocate for myself & Salesforce nonprofit customers. (Costanza-Chock, 2018). In a perfect world, I would not have to do these types of analyses, but– in reality– living in my body means these are some of the issues I consider when performing my day-to-day job.

Lastly, after assessing for consequence and power positionality, I performed an inquiry-advocacy assessment.

Shelbi Gomez developed the inquiry-advocacy matrix at Adobe (https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/inquiry-advocacy-matrix) to help leaders be effective communicators. The matrix teaches leaders to adapt their communication styles strategically depending on their goals. I used Adobe’s inquiry-advocacy matrix to define my objectives and select the most effective communication approach to achieve them. In this case, I wanted to assert myself and influence my team to improve on their proposed solutions. To do so, I called a meeting with key decision-makers and stakeholders. During the meeting I used a process map to outline and discuss the ethical implications of creating a connective data pipeline for enhancing fundraiser donations, as well as the technical and legal implications of assisting customers in developing a donor dashboard solution.

Figure 2. Nonprofits fundraising to programs department data sharing processes.

Recommendations

As part of the presentation, I provided general recommendations, allowing them to review their proposed solutions.

Recommendation 1

I recommended the team explore other avenues to address fundraising transactions for the proposed donor dashboard solution with other cross-functional teams. The research revealed that individual transactions might not be trackable. Still, we could link fundraising efforts to organizational impact for our customers if we took the time to think of potential solutions from other perspectives.

Recommendation 2

For the proposed data pipeline solution that would allow organizations to link fundraising and program data, I suggested that the team include a security and permission structure on the program and delivery database that would allow program managers to control data sharing. The data pipeline would still make the data-sharing processes more “efficient” while protecting constituent data.

ORGANIZATIONAL IMPACT

Product, Feature, and Team Impact

Introducing research as friction allowed the team to understand the complexity and consequences of their proposals. After my presentation, they took some time to consider the findings. Then, the product team decided to forgo their proposed ideas, opting instead to dedicate more time to understanding our customer’s problems via a dedicated working group focused on uncovering our nonprofit clients’ data sharing, interoperability, and integration issues. This team would now be in charge of exploring that fundraising to programs pipeline to develop better solutions. They also decided to segment and deprioritize the proposed features from the product roadmap so that they could dedicate more time to testing future solutions.

This case study demonstrates how friction can drive positive product development and enhance product processes. It also serves as a valuable reminder that what we perceive as ‘inefficiency’ may not always be so and that we should be mindful of what makes our customers different. Employing ethnographic research methods and humanistic frameworks helped me rediscover our customer’s uniqueness while, at the same time, fostering trust and collaboration within my team, which, in turn, ensured our product integrity.

Using frameworks as reflective tools for self-assessment helped me better understand the research findings, the proposed solutions, my team, and my institutional goals from a holistic perspective. The consequence scanning assessment helped me build my argument concerning product proposal impact; the power positionality assessment helped me understand my vulnerabilities and the power dynamics within my team; it also empowered me to leverage my privilege to advocate for nonprofit customers. The inquiry-advocacy matrix helped me assess my comfort with becoming an advocate for our Cloud’s users. It gave me the tools to drive an intelligent and influential conversation with my team. Ultimately, leveraging ethnographic research helped me produce influential and timely research insights, navigate friction, and provide my team with the knowledge that resulted in ethically built solutions that meet our customers’ needs.

REFERENCES CITED

Abramson, Alan. “History of the Nonprofit Sector Part 2: A (Very) Brief History of the U.S. Nonprofit Sector.” Independet Sector, 2019. https://independentsector.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/IS-class-summary-par t2-final.pdf.

Alptraum, Lux. “Silicon Valley’s Obsession with Efficiency Is Fundamentally Rooted in Sexism.” Quartz, February 10, 2017. https://qz.com/906115/silicon-valleys-obsession-with-efficiency-is-fundamentally-rooted-in-sexism.

Baines, Donna. “Neoliberal Restructuring, Activism/Participation, and Social Unionism in the Nonprofit Social Services.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 39, no. 1 (February 1, 2010): 10–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008326681.

CodeRiders. “Top 5 Organizational Structures of Software Firms | Pros & Cons,” 2022. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/top-5-organizational-structures-software-fir ms-pros-cons-coderiders.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. 1st edition. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Corduneanu, Roxana. “Purpose vs. Profit: Making the Case for Both,” 2022. https://action.deloitte.com/insight/2989/purpose-vs-profit-making-the-case-for-bot h. \

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. “Design Justice, A.I., and Escape from the Matrix of Domination.” Journal of Design and Science, July 16, 2018. https://doi.org/10.21428/96c8d426.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (1991): 1241–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

Doteveryone. “Consequence Scanning – an Agile Practice for Responsible Innovators – Doteveryone.” Accessed September 24, 2023. https://doteveryone.org.uk/project/consequence-scanning/.

Ensor, Kristine. “Nonprofit Organizational Charts: What Are They and Why Are They Vital?” Nonprofit Blog (blog), September 8, 2021. https://donorbox.org/nonprofit-blog/nonprofit-org-chart.

Gomez, Shelbi. “The Inquiry-Advocacy Matrix: The Secret to More Effective Communication at Work.” Accessed September 19, 2023. https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/inquiry-advocacy-matrix.

Gupta, Mahesh, and Amarpreet Kohli. “Enterprise Resource Planning Systems and Its Implications for Operations Function.” Technovation 26, no. 5 (May 1, 2006): 687–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.10.005.

J. Boonstra, Jaap, and Kilian M. Bennebroek Gravenhorst. “Power Dynamics and Organizational Change: A Comparison of Perspectives.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 7, no. 2 (June 1998): 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943298398826.

Katz, Rob. “How To Run a Consequence Scanning Workshop.” Salesforce Designer (blog), October 6, 2021. https://medium.com/salesforce-ux/how-to-run-a-consequence-scanning-workshop- 4b14792ea987.

Maier, Florentine, Michael Meyer, and Martin Steinbereithner. “Nonprofit Organizations Becoming Business-Like: A Systematic Review.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45, no. 1 (February 1, 2016): 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014561796.

Mailchimp. “What Is CRM? A Marketer’s Guide.” Accessed August 11, 2023. https://mailchimp.com/crm/what-is-crm/.

Motro, Daphna, Jonathan B. Evans, Aleksander P. J. Ellis, and Lehman Benson. “Race and Reactions to Women’s Expressions of Anger at Work: Examining the Effects of the ‘Angry Black Woman’ Stereotype.” Journal of Applied Psychology 107, no. 1 (January 2022): 142–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000884.

Synopsys. “What Is the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) and How Does It Work? | Synopsys,” 2023. https://www.synopsys.com/glossary/what-is-sdlc.html. Violence, INCITE! Women of Color Against. The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.