During recovery and transition to the ‘new normal’, the loss of agency for patients and families of patients who go through a major health disruptor such as transplant, cancer, or cardio-vascular disease can be profound. Considering this, how can acute care hospitals help solve for caregivers’ loss of agency? And what does the physicality of such effort in the confines of a hospital building look like? The goal of this case study is to (1) demonstrate how ethnographic thinking and design research can help a medical center understand the needs, values, rituals, and agency of a patients and their families; (2) show socio-spatial solutions that can support the transition to the patient’s and family’s new normal.

The ethnographic study showed that the patients and families who go through a major health disruptor struggle with the loss of agency in various ways. While loss of agency can be obtuse, four themes emerged as contributing factors to the overall sense of loss: (1) loss of confidence; (2) loss of familiarity; (3) loss of play; (4) loss of passion. The degree of loss experienced was related to the severity of the health disruptor.

Socio-spatial design solutions resulting from the research included a significant allocation of family-centric space (e.g., experiential learning for family caregiver education, well-being for family support, and family connection rooms), programs, services, products, and partnerships (to relieve and provide permission) for family caregivers to regain elements of agency.

This case study is written before the redesigned protocol and physical space design is completed-and-in-practice. The research to-date, however, was sufficient to persuade the client to commit to redesigning the family/caregiver experience as manifested in the design of the physical space as well as its accompanying protocols.

INTRODUCTION

“It’s hard when you’re trying to see your daughter’s graduation … you’ve waited 17 years for this day, and you’re missing it because you’re 1000 miles from home.” Mia then pulled out her cellphone and showed the video of her 17-year-old daughter in the graduation dress walking down the hospital hallway. “She graduated. Her daddy missed it. We missed it. So she wanted to walk. You see her coming down the hallway? … And the nurses, they’re playing the pomp and circumstance … and I was praying that no one would die during that 30 second walk. There would be no emergencies.”

Mia’s husband, a transplant patient, missed their daughter’s graduation ceremony due to his condition. This was not the only thing that had changed for him and his family compared to their pre-transplant lifestyle. Yet, this major disruption had never stopped the family to strive for navigating a new lifestyle, a new “normal”. The graduation ceremony was not an exception either. Despite all the limitations, the family with the help of a group of nurses rebuilt this ritual for the father by recreating the graduation ceremony in the hospital hallway.

When it comes to settings in which people experience loss of agency, acute care medical facilities are perhaps at the top of the list. Losing control over conscious execution of freedom of choice and power (Bourdieu, 1977; Giddens, 1984; Berger and Luckmann, 1966) for patients and families of patients who go through a major health disruptor such as transplant, cancer, or cardio-vascular disease can be profound. Considering this, what can acute care hospitals do to help patients and caregivers regain their disrupted agency and rebuild a new normal? What is the physicality of this effort in the confines of a hospital building? And ultimately, how would such hospitals be different from conventional ones?

In recent years, the playing field for acute care hospitals has drastically changed. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), a major payor in the U.S. healthcare system, has mandated hospitals to publicly report patients’ satisfaction with hospital care as measured by the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). The HCAHPS survey is intended to standardize collection of patient satisfaction data for the purpose of making objective comparisons across hospitals nationwide, incentivize quality of care improvements, and enhance accountability. HCAHPS measures patient satisfaction using a series of questions categorized under 10 topics covering themes that range from staff communication and responsiveness to cleanliness and quietness of hospital.

However, the big data curated by HCAHPS and other patient satisfaction surveys do not consider or assess the family caregiver experience. Currently, family-centric, standardized metrics do not exist although many healthcare systems identify family-centered care as a highly valued guiding principle. This case study uses mixed-methods approach to demonstrate how ethnographic thinking and design research can (1) help an acute care medical center understand the changes in needs, values, rituals, and agency of family caregivers as they transition to a new normal; and, (2) identify what is needed from the institution to truly support the transition. Specifically, the case study explores the loss of agency within the ecosystem of care and potential design responses to assist in reclaiming agency among family caregivers.

CONTEXT AND SETTING

As part of predesign work for two new bed towers, to be built in a large U.S. city, design researchers from two partnering architecture firms were charged with gathering data and original insights around patient and family experience to generate ‘innovative solutions and unique brand offerings’. An interdisciplinary experience design team was formed to investigate the client’s current patient experience landscape and generate insights to guide future architectural planning and design work.

At the beginning of the project, the institution identified a total of ten service lines. However, after conducting multiple focus groups and journey mapping sessions, these service lines were framed under three Centers of Excellence for the purpose of focusing research efforts. The three Centers of Excellence included the following:

- Heart and Vascular Institute (HVI)

- Oncology and Immunotherapy

- Transplant

JOURNEY FROM BIG DATA TO THICK DATA

To understand the patient experience, researchers started from studying traditional healthcare standard metrics and big data. However, the review of metrics from HCAHPS and CAHPS (Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) along with patient satisfaction scores did not reveal fresh insights or innovative opportunities as they were measuring standardized structure of healthcare delivery and quality of care – all high markings. Suggestions from this initial study included enhancing room size and natural lighting in inpatient rooms. Yet as best practices already established in the field, they were not offering new opportunity or fresh insights that would prompt innovative solutions.

The research team soon realized that to deliver innovative solutions, they must go beyond the industry structure and to gain deep insights into patient and family emotions, beliefs, values, and social systems pertaining to a traumatic health disruptor. Therefore, a mixed-methods approach to collect patient and family experience data was proposed. The research design included ethnographic interviews, participatory methods such as visual listening, and focus groups with patients and families as well as journey mapping workshops and focus groups with providers.

The client institution, however, asked to omit ethnographic interviews with patients and families from the approach and limit the research phase to journey mapping workshops with staff, patients, and families. Being aware of the value of ethnographic and participatory action research for uncovering insights pertaining to patient and family experience, the research team initially agreed to the new plan proposed by the client institution. However, they later used the results from the journey mapping exercise to justify the value of ethnographic field work. The research team did so by showing discrepancies between staff’s perception of care journey with that of patients and families.

The research team facilitated staff and provider workshops and guided a market-based research firm, that held a retainer with client institution, to facilitate an experiential journey map exercise. More than 300 staff members, including providers, clinicians, support professionals, and administrators participated in describing their perspective of the patient/family emotional journey mapping. In tandem, the same emotional journey mapping exercise was conducted with 91 patient and families of diverse health experiences, ages, ethnicities, genders, and geographic locations.

Consequently, the research team’s analysis of all research activities showed a significant discrepancy during patient and family recovery and discharge – staff and providers perceived a positive experience during these phases of patient journey while patient/family expressed emotions such as anxious, unsure, lack of confidence, overwhelmed during their/loved one treatment and recovery.

Identifying similar insights and moments with innovative potential reinforced a focus to step outside of traditional healthcare metrics and tools to understand opportunities that could support patient and family’s confidence, reassurance, and empowerment during treatment and recovery. An updated mixed-methods research design approach was proposed to incorporate ethnography, visual listening, and shadowing observation which lead to key findings in this report on patient and family agency. Finally, a framework comprised of guiding principles and strategies resulting from this effort framed the design and decision making during the subsequent phases of the project.

The following describes the methodology, results, and impact of the study.

METHODS

Emotional journey mapping was one of the methods used to identify key moments in patient/family’s current care journey. During this exercise, data was gathered during a workshop attended by 80 staff members including providers, PAs, RNs, and administrators. The intention was to assess the patient/family care journey as perceive by Subject Matter Experts. During the workshop, participants created five unique patient personas and described the patient/family’s perceived journey by highlighting actions, behaviors, and emotions as touchpoints throughout the continuum of care – which included five key phases of understanding, diagnosis, treatment, recovery, and discharge.

In addition to conducting this exercise with staff, a series of emotional journey mapping sessions were conducted with patient/families. These sessions included a total of seven focus groups each with 10 to 18 patients/families from a range of experiences and demographics who belonged to a particular service line. Each patient/family completed an individual emotional journey map which then was used to create a collective service line journey map. Results of staff perceptions of the patient journey were then compared to those of patients.

Aggregated data from the comparison compiled patient/family needs (from patient/family and staff/provider) that informed overall patient thematic design insights based on overarching project opportunities. However, distinct discrepancies revealed in the following two areas motivated the research team and the institution to broaden the scope of their investigation by including family members.

- For HVI and Transplant, family and patient time during patient recovery that supports lifestyle normalcy and preparing family/patient new normal at discharge.

- Oncology patients’ consultations, procedures, or other aspects of care during treatment and recovery to support lifestyle normalcy.

In framing the value of ethnographic research, it was determined that enhancing recovery and discharge through process improvement was not the solution. To deliver holistic patient and family-centered care, the client institution needed to first understand the overall lifestyle characteristics of patients and families. Only then would it be possible to create new innovative systems that would facilitate lifestyle normalcy during care and educate families on how to adapt to and adopt “a new normal”.

Ethnographic interviews, journey shadowing, visual listening, and observations were the primary research methods used during the targeted research. A total of eight patient/family groupings — two from each CoE (Heart and Vascular Institute, Oncology, Transplant) — were selected. Each ethnographic interview coupled with shadowing interviews of patients and families lasted between three to six hours and began with meeting patients/families at their home, or place of stay, to understand values, rituals, context ques, and lifestyle normalcy before and after the health disruption. Shadowing interviews were then conducted from the time they left their home to the time they either returned to home or left the hospital for a follow up visit.

The quantitative data and the information acquired from tracing patient/family movement during their visit was overlaid, in real-time, with the “thick data” of human behaviors, needs, values, and body language. Finally, visual listening was used, at the conclusion of the interview, to understand the range of places and experiences that could be incorporated to support patient/family normalcy during treatment and recovery as well as to prepare patients/families for their new normal after experiencing a health disruptor (e.g., cancer, transplant, heart, and vascular disease).

FINDINGS

Journey Map Comparison

Comparing staff perceptions of patient journey maps to actual patient journey maps revealed a significant disconnect resulting in an “ah-ha” moment for client leadership as they engaged in an exercise to build empathy for patients and their families. Instead of just showing ways to improve the process and workflow, the research team shifted the focused to the “emotions” and the “why”. Later, the results were themed around micro-interactions, hospitality in healthcare, family-centered care, and supporting a new normal during and after treatment. Not only did emotional journey mapping build rapport and empathy between staff, patients, and families, it served as a framework for staff/providers to understand misperceptions and the significant value of patient/family voice in a broader context than quality of care.

Normal to New Normal

An important finding of the targeted investigation was the need to think differently about patient/family-centric care within the client institution. Ethnographic study of families’ role in patients’ overall recovery and lifestyle transition following a major health disruptor revealed caregivers’ struggle with the loss of agency. While loss of agency can be obtuse, four themes emerged as contributing factors to the overall sense of loss: (1) loss of confidence; (2) loss of familiarity; (3) loss of play; (4) loss of passion. The degree of loss experienced was related to the severity of the health disruptor and each loss relates to a spectrum of normal and new normal.

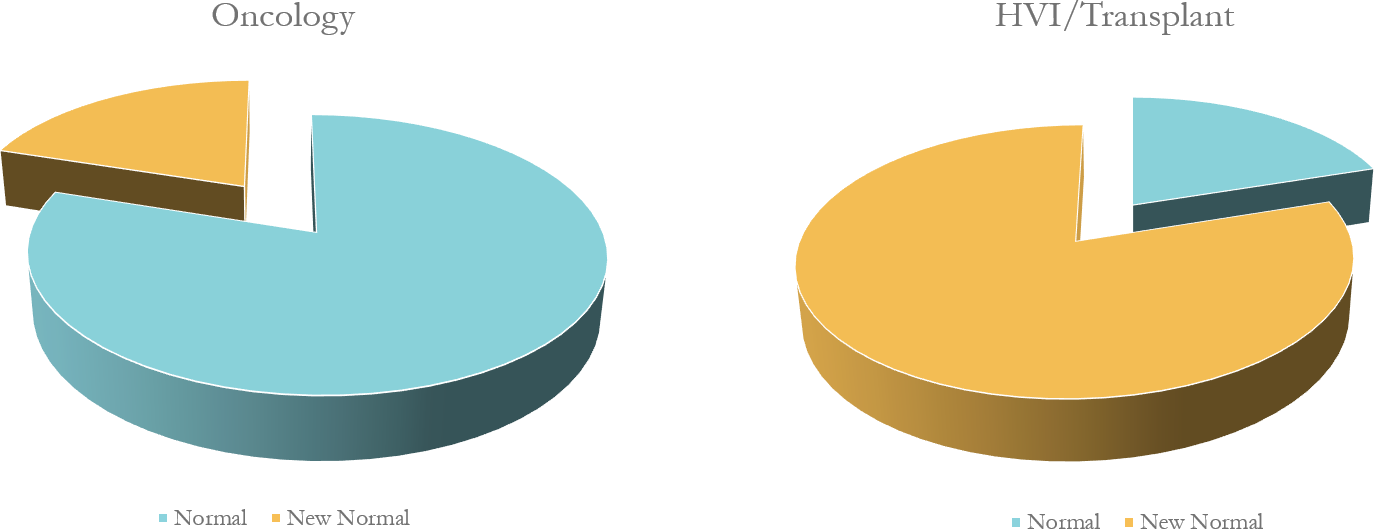

Further analysis indicated a wide spectrum in patient and family needs based on normalcy and new normal across service lines (i.e., Transplant, HVI and Oncology). For example, the need for confidence and new normal were much higher in transplant patients and families than those of oncology patients and families. Oncology patients typically undergo long courses of treatment requiring frequent visits to campus. As a result, they expressed interest in activities and spaces that served to bring normalcy to their time in the hospital. At the other end of the spectrum, transplant patients experienced an intense disruption to their normal lives creating the need to define a “new normal” and associated activities and spaces. Family experiences and needs were especially important for HVI and transplant patients (Graph 1).

Graph 1. Unlike in oncology, transplant patients and families experienced an intense disruption to their normal lives creating the need to define a “new normal” and associated activities and spaces.

Confidence, Familiarity, Passion, and Play

Through collaborative-coding of 100+ page ethnographic transcripts per each interview, four clear themes emerged among all eight patient/family participants. There was a shared experience of loss of their sense of purpose, characterized by the loss of one, or a combination of the following:

- Loss of Confidence: Navigation of a complex healthcare structure, during a traumatic disruption, created a large loss of trust and firm belief in oneself. This applied to patient and equally in family care-giver due increase responsibility for their loved one’s care.

- Loss of Passion: Limited physical and bodily functions often diminish patients’ ability to engage in their profession or hobbies of passion. Patients expressed that losing their job was equivalent to losing their passion.

- Loss of the Familiarity: Patients and families dealing with health issue(s) may experience disruptions in familiar individual / family dynamics, routines, and roles.

- Loss of Play: Due to changes in priorities, play (e.g., hunting, baseball, cooking, playing games together) is often among the first activities that patients and families sacrifice. However, still value time to connect, together, to celebrate, learn, and laugh.

DESIGN SOLUTIONS

Designing through the lens of confidence, familiarity, passion, and play provided a new approach in healthcare design framed by themed values through patient/family agency, not healthcare structure and systems, e.g., waiting, in-patient room, check-in, and others.

Consequently, rebuilding patients’ and families’ agency will be the result of:

- Rebuilding Confidence by providing opportunities to stretch patient/family education to preparing for new normal.

- Example: Partnerships with museums and humanities to incorporate experiential learning & gamification, hands-on immersive learning through home/kitchen simulation for caregiver to practice at-home care, creating at home monitoring and real-time telecare, when needed,

- Rebuilding Passion by providing opportunities for patients to practice a modified version of the original passion.

- Example: Spaces and programs where patients or former patients can provide coaching and share experiences

- Rebuilding the Familiar by providing experiences that maintain a sense of continuity with past experiences of normal and supporting the new normal

- Example: Potential for hosting family celebrations such as birthdays, sitting by a fire to read a book, going out to eat.

- Example: Immersive/simulation education experiences for patients/families such as demonstration kitchens, nutrition education, and grocery shopping, LVAD care simulation, prescription systems.

- Rebuilding Play by allowing for family members’ creative engagement in playful activities.

- Example: Spaces that accommodate playing musical instruments, engaging in art-making, observing or participating in festivals/community outdoor programming.

Characteristics of Desired Amenities/Service/Spaces

Images that resonated with participants included spaces that:

- Provide respite from the isolation of inpatient rooms

- “I wanted to be close but needed a change of scenery. Time for me without feeling guilty”

- Reflect normal life activities (e.g., coffee shop, hair salon)

- “If I can’t feel normal, I want to try and look normal!”

- Integrate with the community

- “Just being around people “living” is refreshing. And [I] want to learn about the city and people.”

- Offer a range of affordable food choices (i.e., healthy and not so healthy)

- “At times, I just want a burger!”

- Engage with opportunities for creativity, learning, socializing, and play

- “We would bring in a guitar to the room and sing. I also bought a bunch of paints to distract us in the room.”

Participants were not interested in:

- Franchised spaces but instead wanted to see the unique characteristics of Pittsburgh reflected in the environment

- Public respite spaces (e.g., massage chairs in open areas)

- Large-scale gyms shared by staff and patients (preferred boutique gym concept)

- Large, extensive shopping areas (preferred smaller, easy to access shopping spaces offering “essentials” (e.g., warm clothing) and special gifts

IMPACTS OF RESEARCH

The major impact of the research resulted in a shift of perspective for the healthcare institution when thinking about patient and family/caregiver needs; life happens when there is a healthcare disruptor vs. a healthcare disruptor happening to life. This can be observed through three actions of the client.

- Design solutions resulting from the research included a significant allocation of square footage to support normalcy and new normal through family-centric needs in solving for loss of confidence, play, familiarity, and passion

- Design space to include experiential learning for family caregiver education, well-being & exercise for family support, and family connection rooms. In addition, connection to community on first floor and opportunity for placemaking in/around campus to intersect community, family, patient (if approved), and staff/provider can connect through “life”.

- Creation of a new patient /family experience committee for oncology and redesign of HVI / Transplant Patient/ Family patient advisory committees (PAC’s) of input and discussion topics. Instead of what do you need while you’re waiting, or checking-in, there is discussion around “confidence”, “empowerment”, “play”, “familiarity”.

- Analysis of experience within the institution’s metrics and incorporation within patient satisfaction scores. In addition, the potential for a family-only survey to understand and create new systems, places, services, and products to support family-centric care, holistically.

Because the physical space is not yet fully constructed and in-use, it is not possible to show impacts on the motivating problem. Thus, specific impact on each action, currently, is unmeasurable. However, impact from the research and process has changed the institution’s thinking about patient and family/caregiver needs and experience through newly formed empathic lens.

CONCLUSION

This study’s conclusions can be defined as two main types of normative and intermediate. The normative conclusions highlight the benefits of iterating through quantitative to qualitative data and methods and leading the client through constructive cycles of experimentation. As mentioned earlier in the paper, ethnographic tools and methods in this study evolved as a result of a negotiation with the client institution. During the research design phase, the research team detailed the ethnographic interviews to be conducted at the patient/family’s home or place of stay. The client institution, however, did not support the research proposal, due to adherence to standard practices to maintain control and safety of sensitive patient/family subjects. Acknowledging the value of ethnographic and participatory action research for assessing patient/family agency, the research team first worked with the client institution to establish the merit of ethnographic fieldwork and then agreed to meet the client “where they were at”. They did so by strategically using the results from the journey mapping exercise as a justification for conducting and lens for framing the in-depth ethnographic fieldwork. As a result, ethnographic interviews were conducted at the patient/family’s place of stay while patient/family focus groups were conducted at the hospital.

Intermediate conclusions included the discovery and definition of lack of agency in a way that was sufficient to persuade the client to commit to redesigning the family/caregiver experience as manifested in the design of the physical space as well as its accompanying protocols. Design decisions were made for patients and families to regain their agency by rebuilding their diminished confidence, often lost passion, familiar rituals in different ways, and creative ways of incorporating play in their lives.

REFERENCES

Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann, 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Doubleday.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice, translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society. Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.