Consumer finance markets are being transformed by the increasing mobility of people, products, technology, and information. This presents challenges for understanding changing consumer behaviour and building adaptable business models. Researchers are rising to meet these challenges by adapting their frameworks and methods to take account of mobility’s effects. I present three cases of method adaptation to consumer finance research (financial diaries, object-centred interviews, social network analysis) and discuss their contributions. The complexity and personalisation of consumer finance requires us to not only be more creative with how we approach research, but also more robust in questioning our assumptions, framing appropriate questions, and designing research that draws frameworks and methods from multiple disciplines.

One can only understand and apply all these new innovations by playing close to the ball and understanding customers’ needs and expectations. It is no longer possible to say what the world is going to look like five years from now. In the past, bankers were ‘scenario thinkers,’ who ran the bank by making strategic choices far in advance. Today, we have to grant more space to short-cycle thinking and optionality. (Alexander Zwart, Senior Product Manager at Rabobank, quoted in Ifrim, Mual and Innopay 2017)

INTRODUCTION

Gone are the days when consumers did their banking in their local village or “high street”: instead, products and providers can (within regulatory and practical limits) reach consumers anywhere around the globe. People access financial services and information as they move around their cities or travel internationally. A person can pay their credit card debt while riding in a train, do their grocery shopping online as they sit in a café, bet on a football match while perched on a public toilet, or buy illicit drugs using Bitcoins as they head out for the night. Along with people and products, information is also far more mobile. People can find extensive product information online, and they can share their personal information far more easily. Business models are also changing, because the “unbundling” of banking, new technologies, and regulatory reform make it is easier for start-ups with highly specialised products to enter the market.

These changes make both the supply side and demand sides of the market more difficult to understand, presenting challenges for understanding changing consumer behaviour and building robust business models (CGI 2014, Muller et al. 2011, Xiao 2008). It is impossible to predict the future: we cannot foresee how consumers will respond, which service providers will come to dominate the market, or what new technologies will threaten data protection methods we currently view as fool-proof.

Zwart (quoted above) and others have argued that, given this uncertainty, our best bet is to focus on what consumers are doing and how their practices are changing. This approach makes sound business sense, since it is consumers, after all, who make purchasing decisions. However, it makes one critical mistake: it assumes that “consumers” are somehow separate from “the market.” But they are not. (Nor are consumers necessarily individual people, but that is a matter for another paper.) To understand what consumers are doing, we need to know as much about market characteristics and trends as we do about consumer themselves. A consumer-centric approach should not end at the front door of the household. It should consider consumer behaviour within market contexts, however messy.

Prediction per se may be out of reach, but we can anticipate likely futures if we adapt our conceptual frameworks and methods to the current state of the market. This will help us plan for risk mitigation while creating products and platforms that benefit society. To do so, it is useful to understand how the market is changing and why. I argue that the root cause of changes in the market for consumer finance is the increasing mobility of technology, products and services, information, and people. I present a framework that takes mobility into account in consumer finance research. First I discuss why mobility is a central feature of money, and explain how it is transforming consumer finance practices today. Second I asses some adaptations of methods to consumer finance research. Finally, I argue that since mobility is generating more market diversity, a greater number of research problems are located in the long tails. This means we are unlikely to find answers through research that takes a normative, business-as-usual approach. Instead, we should look more broadly across methods, disciplines, and professions for clues that can help us shape robust research.

CONSUMER FINANCE ON THE MOVE

Consumer finance globally is undergoing a transformation resulting from the increasing mobility of people, products, and information. These changes make both the supply side and demand sides of the market far more difficult to understand, presenting challenges for understanding changing consumer behaviour and building robust business models. The digitization of financial services and the near-universal penetration of the Internet has transformed the market for financial services for both consumers and financial service providers alike. Digital financial services are integral to the transformation of consumer finance from something that happens within domestic market, defined by national borders, to a practice that integrates (or implicates people, providers, and regulatory bodies around the globe.

For consumers, the proliferation and specialization of financial services means that they are no longer limited to using local providers: instead, they can choose between products and services from around the world. While many people still choose to use local products, the trend is towards the diversification on all fronts: products, providers, point of origin, and so on. For service providers, the ability to access both consumers and other businesses through the Internet has transformed business models. While traditional retail banks retain a strong position in consumer finance markets, they need to partnering with other providers in order to retain access to consumers, and innovate new products and services.

This increasing mobility and market transformation is partially a manifestation of globalization. However, financial products and services present a special case, because financial instruments have always depended on mobility in order to function. Money, whether in the form of coins, shells, banknotes, tally sticks, promissory notes, or digital currency, has to be transportable if it is to be used as a means of payment between geographically distant buyers and sellers. Shifting to electronic money increases money’s functionality and transaction speed, but it does not introduce a new feature to money.

Mobility also drives the spread of financial technologies around the world. When people migrate beyond their locales, they take their monetary technologies with them. From as early as the 16th century, global trade propelled the development of financial tools, including promissory notes and the stock exchange. By the mid-1800s, telecommunications systems, such as the trans-Atlantic telegraph, were used to wire money internationally (Stearns 2011). For the first time, monetary values no longer needed to be moved in the form of tangible material things, such as paper or metal, but instead could be sent in the form of an electric current. Hence the basis for digitization was born. By the early 20th century, the coins and banknotes that we recognize today had come to dominate over alternative forms of money (such as shells, livestock, and precious metals).

During the second half of the 20th century, consumer finance in wealthy countries underwent a process of centralization as people came to rely on banks to supply all their financial needs, including savings, cheques, personal loans, mortgages, and life insurance. Thus retail banks took up a prominent role in the development of formal financial products and services globally. For decades, in many countries everyday banking primarily involved visiting a bank branch in one’s local town. Other financial services providers existed, including international money transfer services, insurance companies, pawnbrokers, and loan offices, but they rarely threatened the monopoly of banks.

The dominance of retail banks was shaken by the spread of mobile devices and Internet access (Maurer, 2015). Retail banks continue to dominate consumer finance, with annual revenues amounting to around $3.4 trillion globally (McKinsey 2012). However, transactions are increasingly digital and international, and this creates a basis for the proliferation of services beyond banks. The World Payments Report 2013 states that in 2012 there were around 333 billion non-cash payment transactions, and that m-payment transactions are expected to reach 28.9 billion in 2014 (CapGemini 2013). In 2012, global remittances reached $401 billion (World Bank 2015). At least as important as revenue and transaction figures, are the numbers of people served. There are around five billion adults around the world using financial services, of which approximately two billion adults worldwide are without a formal bank account (World Bank 2015; Demirjuc-Kunt 2012). Nearly all adults in the world—and many minors—consume financial products and services. Even my fourteen-year-old niece bought travel insurance on her iPhone before heading away on a school trip.

In the more traditional retail sector, consumers are still provided for by retail banks, credit unions, mortgage brokers, and payday loans companies, among others. At a national level, the digitization of finance has resulted in an increase of domestic products and providers, such as transport cards, online payment systems, and digitized parking meters and applications. At a global level, consumers can access a wide range of monetary and finance tools, including Google Wallet, Paypal, Bitcoin, money transfer services, insurance products, and investment advice. Newer, non-bank industries include payments services, mobile banking, mobile money, e-wallets, and microcredit.

In countries with large “unbanked” populations, the technologization of finance is helping people to skip the transition from retail banks to other service providers altogether. Extending banking networks to cover larger geographical areas requires a great deal of infrastructure and investment. Instead of investing so heavily in banks, basic financial services are being offered through microfinance agencies and mobile phone-based systems. Mobile money is an example of banks partnering with mobile money operators (MMOs), often telecommunications companies, to provide basic banking services via ordinary mobile phones. Mobile money gives people access to a range of services under the one platform, including domestic and international transfers, merchant payments, savings accounts, insurance, and credit. These services replace or complement a wide array of informal services, speeding up transactions and reducing costs.

Consumer finance service providers have become dependent upon business-to-business collaboration. Just as the apparel industry has long outsourced production throughout a widely distributed value chain, so is consumer finance moving from a situation in which retail banks offer a full-service model to the radical specialization of production and distribution. Rather than building all their products and services in-house, banks increasingly partner with third party providers, either to reduce costs or avoid being left behind. In the past, strict regulations and the need for substantial start-up capital limited financial service providers to a mere handful for each jurisdiction. Today, however, it is far easier for new players to enter the market in most countries. This is partly due to the relaxation of regulations, and partly due to the fact that technology makes it far easier to bring products to market and reach consumers. Non-bank providers have a several advantages over traditional banks, including low overheads, limited capital requirements, no legacy systems, and often a more flexible corporate culture. In response, banks have had to alter their business models. Banks will probably continue to play an important role in this market, but the interfaces (APIs) behind the software customers use to access services will increasingly be branded with non-bank names.

The development of this post-Fordist production chain is still very much incomplete, and there is a great deal of uncertainty in the market. First, the instability of regulations means that it is risky for companies to plan for the future, since they do not know what products and services they will be permitted to provide, how to provide them, or to whom they can market them. Second, despite intense speculation by fintech analysts, it is far from clear which companies will emerge as the dominant financial service providers. Business must speculate on where their main competition lies, and which companies they would best collaborate with. Third, while data analysis can identify current trends, the market is simply too complex (and extensive) to make robust predictions.

Consumer behaviour is particularly difficult to predict, since it is necessary to both quantify trends and understand how people make choices with respect to their current and future needs. Yet we have little idea which directions these transformations will take, or what issues consumers will encounter in the near future. Technologists have a tendency to be optimistic when it comes to imagining the future of financial consumption, especially when it comes to imagining the potential of innovative technologies such as blockchain and product APIs. Yes, it is true that there are some exciting financial technologies and products appearing on the market, and promises of further innovation. Yes, it is true that many consumers are experimenting with new kinds of products and services, and that their choices expand substantially when they can access a global marketplace. But in their optimism, some technologists idealize what is possible without sufficiently taking into account actual human behaviour, which often follows a different set of norms and rules that don’t fit into either old or new business models.

Promises of beneficial change need to be considered alongside consumers’ risk profiles, limitations, and preferences. Risks to consumers will arise from technological innovation and new ways of consuming products. For example, some experts are concerned that innovation in financial product APIs present risks to security and privacy. Informed consent is a big issue with respect to data, especially for consumers who are less technologically literate. As Gijs Boudewijn (2017) of the Dutch Payment Association notes:

It is likely that it would be very difficult for consumers to understand the multiplicity of ways in which they could access their account information, depending on the providers and/or the interfaces used by those providers, and therefore to understand the implications of giving consent.

Another limitation long noted by experts and financial institutions is that financial products are known to be “dissatisfiers,” products that people aren’t really interested in, but which they must use to achieve other ends (e.g., paying for insurance online). If people are uninterested in financial products, will they embrace the choices that open banking and financial service diversification offer? Or will they keep using the same old products in the same ways as before? Which kinds of consumers will diversify their choices, and which will not? Who will benefit and who will be exposed to greater risk? Consumer finance researchers are faced with the task of tracking these diverse and complex changes and predicting their effects.

Figure 1. In Haiti, people send money and make payments using an ordinary mobile phone. Photograph © Erin B. Taylor.

MOBILITY AS A CENTREPIECE IN FRAMEWORKS AND METHODS

Understanding consumers in a complex and volatile market requires us to broaden our framework. Asking a research question at the micro level, such as “Do customers prefer the orange or red logo?” makes perfect sense when making specific design decisions, but it does not ultimately help us to understand why people do the things they do in a complex and fast-changing market. We must be open to choosing methods that work, rather than sticking with methods we are used to. Many, if not all, of the changes occurring in consumer finance have some kind of mobility consideration at their core. We can classify these mobility questions into four different kinds:

Table 1. Mobility framework for consumer finance research

| Effects | Benefits for consumers | Business challenges | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technological mobility | The universalisation of mobile devices and Internet access impacts business models and consumer practices | – Improved platforms for service provision – Services have more functionality – Services are mobile |

– Designing products for now – Designing products for an unknown future – Understanding how users adapt to changing technologies – Security & fraud |

| Informational mobility | Consumers can access information about a diverse range of financial services originating from around the globe | – Increased ability to make informed choices – Increased peer-to-peer communication about products, services, providers |

– Getting product & service information to consumers – Competing in a crowded informational market – Information quality – Understanding who consumers trust and why |

| Product / service mobility | Consumers can purchase financial products and services from around the globe | – Increased choice of providers – Greater range of products / services – More specialised products / services |

– Global market segmentation – Identifying competitors in unfamiliar markets – Getting services to distant consumers |

| Human mobility | Greater number of transaction locations / people influence financial practices as they migrate and travel | – Lowered transaction costs – Increased convenience – Increased peer-to-peer influence |

– Meeting needs of consumers who travel across borders – Serving shift to mobile financial management |

Innovative methods in consumer financial research can better illuminate consumers’ thought processes and practices as they adapt to a shifting market, and also help businesses to adapt their product development and business models. Researchers from both industry and academia are innovating new ways to record and analyse the financial behaviours of individuals and households. Quantitative approaches that make use of massive amounts of personal data have received a great deal of attention for their ability to illuminate behaviour and identify market trends. Rather than repeat the many discussions on the value of “big data,” in this paper I focus on innovations in qualitative methods (some of which include quantitative components. Methods such as ethnography, interview methods, financial diaries, online / offline studies, experiments, and social network analysis are being reconfigured to account for the increasing mobility of products and services through accessible digital spaces and technologies.

Qualitative methods are particularly adaptable to researching in fast-changing environments because they are open-ended, which enables them to be adapted to changing circumstances in the field. They are also specifically designed to look at the larger context in which human behaviour occurs. For example, in our research on mobile money use in Haiti, my colleagues and I watched how people made transactions on their phones, talked with them about why they made certain choices, and followed them as they went about their daily life to witness what circumstances prompted certain behaviours. We also tested the mobile money infrastructure ourselves in dozens of locations, talked with regulators and telecommunications providers, and analysed mobile network maps. Ultimately all this information fed into a report, Mobile Money in Haiti: Potentials and Challenges (Taylor, Baptiste and Horst 2011), in which we mapped out the possibilities for the future of mobile money, given the current state of the market, infrastructure, regulations, and consumer needs.

Below I describe recent adaptations of qualitative methods to explore mobility issues in consumer finance, presenting three methods and case studies that were originally described in the Consumer Finance Research Methods Toolkit (CFRM Toolkit) (Taylor and Lynch 2016), a collaboration between Canela Consulting and the Institute for Money, Technology, and Financial Inclusion (IMTFI). All of these methods and case studies are “ethnographic” in that they pay attention to context and incorporate a range of methods or sub-methods within a single research project. I briefly summarize the methods, present the case studies, and discuss their implications for understanding the effects of mobility on consumers’ financial behaviour.

Financial Diaries

Many assumptions about how people manage their finances are incorrect or misguided. Financial diary studies are an excellent tool to investigate how a household manages its entire financial portfolio, and tend to excel at overturning our assumptions. This was well demonstrated by the Portfolios of the Poor financial diary study (Collins et al. 2009). First, this study demonstrated that poor people’s financial problems do not generally stem from financial mismanagement. Rather, they stem from a lack of resources. Second, it showed that people are highly adept at combining a diverse range of formal and informal tools to manage scarce resources. Third, it demonstrated that people use financial tools in combination, not in isolation. If we focus on how people use a single tool, rather than how they manage their entire “portfolios” and toolkits, then we run the risk of misunderstanding how and why they choose certain tools.

Briefly, financial diaries are a method of collecting data on financial behaviours by using a “diary” to record transactions. The financial diary method was pioneered in the late 1990s by a group of researchers with expertise in economics, finance, anthropology, development, and architecture (see description in Taylor and Lynch 2016; see also Collins et al. 2009). The method has since been applied by numerous social scientists working in different parts of the world.

Tracking what instruments people use in the course of a week, month, or year provides valuable information about how people choose between financial instruments depending upon the time of day, location, and the activity they are undertaking. When tracked for long enough, it can also show how, when, and why people add or discard financial instruments from their toolkits. Are customers dissuaded because a new service has features they don’t like? Or do they feel they already have something in their financial toolkit that performs a similar service? Examining people’s entire financial toolkits over time gives us a chance to answer these questions.

Because financial diaries examine entire portfolios, they are an excellent method to investigate the effects of digitisation on consumer behaviour. As consumer finance goes digital, it is becoming more difficult to pinpoint what people do and why they do it. We know that people use a far wider range of services than just banks. We know that consumers are likely to benefit from greater choice. But digitization also presents new (or enhanced) challenges and risks. Will literacies (financial, technological, informational) become a greater challenge, as people have access to more information and services via devices? Where does fraud risk stem from, and who will be most affected? How will people expand their financial toolboxes, and why? Will they continue to use non-digital services, even if digital options are available? How will they combine tools from online and offline, formal and informal sources?

Case Study: Financial Diaries and Household Management – Alexandra Mack, a Research Fellow at Pitney Bowes, conducted a financial diary study as part of research into financial communications management in the United States. Mack was interested in how “financial communications” impacted financial management within a household. She had already used other methods, including interviews and scrapbooking, to collect data on financial behaviour. The financial diaries were an opportunity to dig deeper into some of the issues she had discovered, such as how financial management varies by life stage, and factors that impact attitudes toward new technologies for managing finances.

Mack’s financial diary was conducted entirely online, using software called Revelation. Participants were able to record their diaries in their own time over the course of a week. They were required to log in to the site each day and complete a variety of activities. These included answering questions, keeping logs of some financial interactions, and having group discussions with other participants. They would also take pictures using their digital camera or camera phone and post them to the project site.

Figure 2. The online financial diary study asked people to upload photos of their financial management systems. This household used envelopes to store receipts for tax purposes. Photograph © Alexandra Mack.

Participants were asked to report every day on communications they received from banks and billers, as well as on financial interactions other than shopping. Other questions asked participants to discuss their use of mobile applications, practices around bill payments, and their experiences with fraud. In group discussions, participants were asked questions such as, “What annoys or bothers you most about your financial communications?”

Mack found the method suitable to draw a broad picture of people’s financial behaviours, the products they use, and their financial communications. While not longitudinal, she was able to ask questions about changing practices and what prompted shifts in individuals’ behaviours. Because the interactions lasted over several days, Mack could query the subjects on different topics that might have felt disconnected if asked back to back in an interview. What began as a study of financial communications evolved into a larger project around financial management.

What can companies learn from Mack’s experience? Like Portfolios of the Poor, Mack’s findings show that people’s financial behaviours are complex and dynamic. Her study provides insights into mobility by demonstrating that people’s financial communications incorporate a wide variety of online and offline sources and media: shopping receipts, mobile apps, computers, letters in the mail, and so on. Some of these are not financial services per se, but are part of the supporting cast that makes transactions work. Her results show that understanding the impacts of digital finance require also looking at practices in the “analogue” world.

Object-Centred Interview Methods

In object-centred interviews, props are incorporated into a verbal interview with the goal of prompting conversation on particular topics. The interviewer may introduce objects, such as a product prototype or flash cards, or objects may belong to the interviewee, such as the contents of the interviewee’s wallet or the devices they use for banking. These interviews may take place in people’s homes or in public places (e.g., to learn how people manage money while on the move).

Object-centred interview methods are particularly useful in consumer finance research because personal and household finances can be complicate and messy, and focusing on concrete material objects can help people to recall their financial management procedures. People often have multiple income streams, combine incomes, or help manage the financial situations of family members. Business records may or may not be kept separate from personal finances. People rarely keep all their financial information in one place, and find it difficult to explain their financial management processes to others. When you ask people to show you their spreadsheets, credit cards, bills, mobile apps, and other financial instruments, it prompts them to remember how their own finances work. If we want to generate insight into what kinds of financial products people might need, then we need to know what they currently use, and we can only know this if we ask the right questions, in the right way.

Like financial diaries, object-centred interviews are useful to map out entire financial portfolios. But whereas financial diaries rely on verbal reporting, object-centred interviews allow the researcher to discuss the physical properties of objects. Benefits include eliciting conversation about how objects are used and why, prompting people to remember what products/services they use and how they use them, and assisting the participant and researcher to discuss visual, audio, tactile, and haptic aspects of objects. Consumers can show researchers what they do or don’t like about a particular product or service, and can explain why they feel the way they do. Much has been written about “financial literacy” as a barrier to money management and technology adoption, but often people’s reluctance has more to do with user experience, trust in the provider, a fear of facing their money head-on, or many other factors. Questioning interviewees about products they do like can elicit insights into what products features encourage usage. Conversely, questioning interviewees about products they don’t like can shed light on whether there are design issues or other factors at play.

Object-centred studies also have many benefits for researching mobility in consumer finance. These days, there are few financial transactions that individuals cannot complete while away from home, using a combination of their mobile phone, bank cards, cash, store cards, and discount cards. When away from home, people use their phone to check their bank balances, transfer money, pay their friends, check in and out of public transport, and use an array of apps to make investments, shop, and so on. Some people still prefer to make purchases and do online banking using their computer rather than their phone, but my current “portable kit” research in the Netherlands (in its early stages) indicates that even when people are at home, they would rather use their phone to complete transactions than have to get off the couch and go to the computer. This example is somewhat ironic, because the mobile phone allows people to be less mobile rather than more (they can stay on the couch!). Yet it is the very mobility of the mobile phone that permits users to stay immobile. Material objects play a critical role in shaping new financial practices.

Case Study: Using and Studying Objects to Track Finances – Jofish Kaye from Yahoo Labs and his team in the San Francisco Bay area conducted a preliminary study with fourteen interviewees, aged 26-29, with incomes ranging from US$18,000 – US$150,000 per year. As described in their paper, “Money Talks: Tracking Personal Finances,” the team incorporated multiple object-centred exercises to try to piece together a picture of participants’ financial management.

Kaye and his team wanted to explore the range of ways in which people keep track of their finances. They devised an interview structure that incorporated a range of static and interactive objects,

including financial maps drawn by interviewees, financial calendars filled out by interviewees, index cards with text for interviewees to choose and discuss, the contents of interviewees’ wallets, guided tours of interviewees’ homes, and computers and mobile devices used for financial management.

Few of the interviewees had a comprehensive idea of their own financial situation. In fact, many reported keeping their financial information in their head—a location that is certainly not suitable for object-based interviews. As Kaye and his co-authors recount, “the most common tool that people used to keep track of the overall state of their finances was nothing at all. Even in cases where interviewees used computer programs, mobile device applications, excel spreadsheets, and paper-based accounts to track financial flows, they rarely tracked every aspect of their finances. For example, one photographer tracked her business expenses but not her personal ones, and a mother tracked her college-aged children’s credit card use but did not track details of her own expenditures.

Figure 3. People typically carry an assortment of cash, cards and receipts. Photograph © Jofish Kaye.

Contrary to traditional economic schools of thought, the researchers point out that interviewees engaged in behaviours that seem “irrational” if considered from a purely financial perspective, but which make sense when other social norms and values are taken into account. They explain:

People make financial decisions based on their emotional, historical, familial and personal backgrounds in addition to financial considerations. (cited in Taylor and Lynch 2016)

Overall, this study indicates that people’s methods of financial management are dictated by what is important to them, and may have little or nothing to do with optimal financial decision-making. When trying to understand people’s financial behaviours, then, it is important to explore their motivations. For example, these days there are many tools for consumers to track their finances (such as Mint or Bill Guard), but few people use them. Why not? Kaye et al’s research suggests that people’s reluctance to use these tools is not necessarily irrational, even if it would bring them more transparency and visibility over their finances. But choosing new financial management tools, and learning to use them, entails transaction costs. It takes time to work out which tools are suitable and which providers can be trusted with one’s data. It then takes longer to test out a tool, figure out if it fits with the household’s financial flows and needs, and incorporate its use into everyday life. Why would a consumer take on new, specialized products if it just means one more thing to think about?

No matter how good financial management programs and apps are, consumers won’t necessarily adopt them if they perceive other barriers to exist (e.g., transaction costs, trust, workflow). Object-centred interviews give consumers a chance not only to talk about the issues they face using their current financial tools, but also to explain why they might not use other tools, and show the researcher what kinds of stumbling blocks they encounter. This is critical because it helps us identify scenarios in which a “failure” to stay “up-to-date” is not a failure at all, but an expression of a preference or a practical choice. Seen in this light, the terms “early adopter” and “laggard” are misnomers. Rather, the laggards are the practitioners who refuse to understand the user’s point of view and adapt our frameworks and methods accordingly.

Social Network Analysis

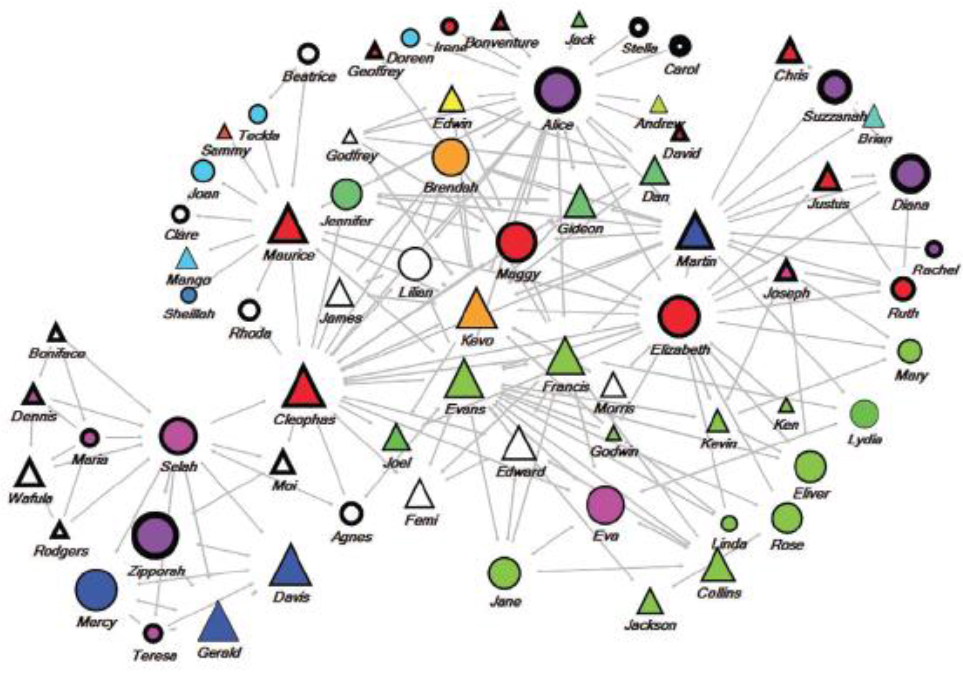

An interesting application of interview techniques is in the analysis of social networks. In social network analysis (SNA), interviews and surveys are used to collect data on networks, which can be analysed either qualitatively or quantitatively. Quantitative interview data can be used to map nodes and connections in social networks. The resulting visualisations are an excellent way to see clearly who is connected to whom, and whether a social network is open (loose connections) or closed (close ties among group members). Qualitative interview data can be used to explain what drives social networks. For example, interviewees can be asked to explain why particular connections exist, how they are maintained, and how they have changed over time. In other words, whereas the quantitative data tells the “what,” qualitative data tells the “how.” As anthropologist Sibel Kusimba explains:

Social network analysis is good because it reveals different kinds of social relationships. It also provides quantitative assessments in terms of size and number of ties. These can also become apparent through ethnographic interviews but SNA makes it clearer. We need both because the ethnographic interviews give context. It’s also good to follow up SNA and do another study in a few years (or other appropriate time frame) because then you can see the social network change. (cited in Taylor and Lynch 2016)

Social network analysis is particularly useful for studying patterns of circulation, such as remittances, conditional cash transfers, gifts, and other forms of payments. It is handy for analysing mobile money transactions, in which users are often individuals who send and receive money for social purposes as much as for economic ones. It shows not only who is connected to whom, but also demonstrates how and why money moves across large geographic areas.

Case Study: Social Network Analysis of Money Circulation in Kenya – Sibel Kusimba and her colleagues conducted a study of mobile money in Kenya, where at least 60% of adults are unbanked. Mobile money was launched in Kenya in 2007 and is widely recognized as the world’s most successful mobile money service. Kusimba and her team were interested in discovering how rural Kenyans were networked through mobile money and the reasons why they sent money. They wanted to find out whether common assumptions about mobile money—that it empowers individuals, stimulates entrepreneurship, and reflects rural-urban migration patterns—reflect Kenyans’ experiences of using mobile money services.

The team undertook research in rural Kenya in 2012. They conducted participant observation, research interviews, and survey questionnaires with more than 300 Kenyans, 80% of whom were farmers. They also conducted interviews with a smaller sample of Kenyans living in Chicago. The researchers carried out different kinds of interviews to elicit qualitative and quantitative data.

In-depth interviews provided background and contextual information about people’s experiences, feelings, social lives, and economic practices. During interviews, the researchers drew up kinship charts. They asked interviewees to tell them to whom they had sent money in the last year and who had sent them money. For the quantitative part of the study, the team interviewed between 3-10 individuals from 14 families. Each interviewee was asked to name all of the relatives that they had sent money to, or received money from, in the previous year. Most interviewees had sent money to 5-9 people. Where possible, the researchers then contacted the individuals that had been mentioned, and approached them for an interview as well. They entered the resulting matrices into R, statistical computing software that can be used to draw social networks diagrams. They could then map out the directions and frequencies of money flow, and to understand the relationships that remittances mediated.

Kusimba and her team chose to ask people to list the names of people they had transacted with rather than the amounts of money they had sent. There were two reasons for this. First, people tended to be inaccurate in recalling quantities of money. Second, many people did not like to talk about money directly. This was especially the case with men who would organize large ritual ceremonies that could cost up to 26,000 Kenyan shillings. Whereas women would admit that they asked family and friends for financial assistance, men preferred to say that they had collected debts owed to them.

Figure 4. A visualisation of a remittance network in Kenya, generated by social network analysis. Photograph © Sibel Kusimba, Yang Yang, and Nitesh Chawla 2015.

- Visualisations help them to clearly see and analyse the connections in a way that is difficult or impossible with interviews

- They could tell which networks were “open” or “closed”

- They obtained a sense of who was “brokering” the gaps in networks

- As SNA is a statistical technique, the networks could be examined in terms of size, number of ties, and other parameters

Social network analysis has limitations as well as benefits. Like any model, it simplifies reality, collapsing a lot of information about family ties and obligations. People send money for a variety of reasons, including deep kinship ties, social obligation, or as a debt, but these differences are not generally visible in social network models (unless survey data are well-complimented by interview data). Whereas social network modelling shows what people do, in-depth interviews demonstrate why they do it.

Methodologically, networks drawn from interview data need to be treated as samples. People forget or intentionally omit their connections for various reasons. Like any other kind of ethnographic information, information needs to be verified wherever possible by talking to the people who an interviewee says they have sent money to or received money from. This sometimes yields contradictory information, but can also improve certainty as to the accuracy of data if different interviewees’ accounts agree.

The team’s combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis of social networks resulted in a wide array of discoveries. Many of the findings contradict common assumptions about how mobile money operates as a social and economic tool:

- The assumption that primarily “individuals” use mobile money to conduct person-to-person transfers or for their own particular purposes, such as saving money. In contrast, the study argues that it is better to conceptualize mobile money as created by collectives and groups.

- Promoters of mobile money for development often represent the service as a tool that empowers people both socially and economically. Sending money via a mobile phone can present a significant reduction in economic and transaction costs compared to other kinds of financial services. However, most people use mobile money to reach out to their traditional networks, not to create new ones or invent entirely new practices. Moreover, its functions and uses are sufficiently different from those of mainstream banking that it does not act as a close supplement.

- Mobile money is often seen to benefit women because it provides a way to make transactions privately, and this can help women gain some autonomy from their husbands and other men. But while women tend to receive a large share of remittances, they often view mobile money as something that helps them cope rather than empowering them. This is because productive wealth is tied up in land and stock, which are predominantly controlled by men.

SNA has many potential applications in consumer finance, as it can be used to track all kinds of mobility, and through any conceivable actors. As well as showing how money circulates (product / service mobility), it could easily be used to show how information moves through a network, which would be highly useful for demonstrating how word-of-mouth contributes to service uptake (e.g., friends and family recommending services to each other).

On the supply side, SNA could be used to map out business relationships and show how they change over time, helping us to understand how business collaborations are changing, and how different sized businesses work together (e.g., start-ups, medium-sized enterprises and large enterprises). It may also be used to track how talent flows around the market, which may help solve the chronic labour shortage problems that plague technology in particular.

In short, when implemented robustly, SNA can be used to show how just about anything moves around and why. SNA is perhaps our most useful predictive tool due to the way it combines qualitative and quantitative information.

PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER

Mobility is at the heart of money itself and many of the practices that drive consumer behaviours, business models, technological development, and the dissemination of information. Most importantly, mobility is changing the structure of consumer finance markets. More diversity among providers and products means a greater range of problems to solve. By definition, this entails a flattening of the bell curve, such that fewer problems are falling within a normal distribution, and instead are tending more towards the long tails. This means that we can no longer rely on our standard ways of thinking and research methods to work.

For many years now, people have been urging us to “think outside the box,” but what people mean by this is rather unclear and unhelpful. We generally associate out-of-the-box thinking with being creative, coming up with new ideas, and innovating. But we actually need a far more robust approach than this haphazard means of generating ideas and solutions. We should not rely on chance to guide our research, but instead on a solid, comprehensive knowledge of different frameworks and research methods. Otherwise we will continue to look hopefully, yet hopelessly, towards normative sources of information—the media, self-styled thought leaders, and large research consultancies—which cannot provide us with the information we need. Research reports by the likes of Deloitte, Capgemini, and PWC provide useful analysis, but they depend upon in-house surveys and normalised data sets to make their claims. Their reports largely address problems that fall within the bell curve, not in the long tails. This means they miss critical information for businesses facing highly specific problems.

Take, for example, a widespread issue in the insurance industry. Insurance professionals complain that they struggle to sell insurance products because people don’t want to think about their own death. Yet historical and contemporary evidence from social science research indicates that this assumption is wrong. Geographically and historically, life insurance has been one of the most popular insurance products. Could it be that there is no ‘natural’ fear of either insurance products or death that is deterring people? Perhaps people’s aversion to life insurance is due to something else; for example, distrust of insurance companies, a dislike of the way product information is presented, or perceptions of choice.

The only way that an incorrect assumption such as this can be overturned is by adopting a rigorous approach to asking questions, and being prepared to look to a wide array of knowledge sources for clues. Many academic disciplines have critical things to say about human behaviour and our changing world, and a wide range of methods with which to generate, ask, and answer questions. For example, there are many disciplines that already produce research that can quickly challenge our insurance salesman’s assumptions, including sociology, anthropology, political science, computer science, psychology, and behavioural economics. But we cannot blame the salesman—finding this research is not his job. Businesses working in consumer finance do not usually have in-house expertise in methods and frameworks, and even if they do, trawling through this research and learning about methods accrues far too many transaction costs to make it a viable proposition.

In contrast, research professionals armed with a broad and robust knowledge of contemporary consumer research and a wide variety of methods are in a strong position to ask pertinent questions regarding how consumer finance markets and consumers are behaving, why, and what likely directions markets are headed. There are many ways this can be achieved. The mobility framework I have presented in this paper is one tool to generate questions relevant to understanding chances in consumer finance.

As the case studies show, most methods geared towards understanding mobility produce data that covers different kinds of mobility: technological, informational, human, and product / service mobility. Social network analysis can be used to track the movement of virtually anything, and is especially valuable because it can show what flows (whether tangible or intangible), where it flows to, its direction, frequency, and quantities, and the relationships between people sending things to each other. Its potential value for consumer finance research is immense, since so many business problems are affected by mobility issues.

Like social network analysis, financial diaries can collect both qualitative and quantitative data and link them together. Their main value stems from the fact that they are used to collect data about people’s entire financial portfolios and toolkits, and can track how these change over time (and why). They could also be adapted to investigate informational mobility, if questions are included that ask people what they know about different products, services, companies, trends, and so on. Compared with SNA they are less adept at examining human mobility, but they could easily be coupled with SNA to produce similar network data. Similarly, when used alone they do not generally do not produce much information about user experience, but they can be adapted to include more in-depth and object-centred interview methods.

Whereas SNA and financial diaries focus more on flows of information and money, object-centred interviews focus on material things. As such, they are especially useful for investigating how people use certain financial products and services, or manage documents and information relating to those services (e.g, receipts, bills, etc.). They are also useful for examining how people use financial tools while on the move, such as using phones, cards, and cash in public places.

We still have little idea how the shift from computer to “portable kit” (usually phone, cards, and cash) is affecting financial management. What happens when people transact in public? Do they make different purchasing decisions when they can manage their finances while in a shop? Are they more or less aware of what they spend when they use contactless payment versus ordinary bank card or cash? Are people exposed to greater or lesser risk of fraud or theft when their payments are digital? There is unlikely to be one universal answer to any of these questions, since people’s preferences and personalities are diverse. But object-centred interviews can demonstrate the range of ways in which people respond, and help us think about what products to develop for whom, and how to build safety features into products and services.

Ignorance drives our creativity, argues neuroscientist Stuart Firestein, but it is our professional knowledge that helps us frame good questions. The very mobility that is reshaping consumer finance practices also makes it possible for us to access the information we need to expand our professional capacities as knowledge experts.

Erin B. Taylor is an economic anthropologist specializing in research on financial behaviour. She is the author of Materializing Poverty: How the Poor Transform Their Lives (2013, AltaMira). Erin holds the positions of Principal Consultant at Canela Consulting and Senior Researcher at Holland FinTech. Email: erin.taylor@canela-group.com

NOTES

Acknowledgments – This paper is based on a collaboration between Canela Consulting (with Gawain Lynch) and the Institute for Money, Technology, and Financial Inclusion, and partially sponsored by Holland FinTech. Sibel Kusimba, Jofish Kaye, and Alexandra Mack generously provided the case studies discussed in the toolkit and this article. Thanks to Simon Lelieveldt for giving me access to his papers, which influenced my use of the concept of the dissatisfier. Finally, many thanks to Gawain Lynch for his comments on this paper.

REFERENCES CITED

Boudewijn, Gijs

2017. Keep the Consumer in Control! In Open Banking & APIs Report 2017: A New Era of Innovation in Banking, edited by Oana Ifrim, Mélisande Mual and Innopay. Paypers, https://mail.google.com/mail/u/2/#search/paypers/15ddf57d07964571.

Capgemini

2013. Capgemini World Payments Report, http://www.capgemini.com/resource-file-access/resource/pdf/wpr_2013.pdf

CGI

2014. Understanding Financial Consumers in the Digital Era: A Survey and Perspective on Emerging Financial Consumer Trends.

Demirjuc-Kunt, Asli

2012. Measuring Financial Exclusion: How Many People Are Unbanked, CGAP, 12 April, http://www.cgap.org/blog/measuring-financial-exclusion-how-many-people-are-unbanked

Collins, Daryl, Jonathan Morduch, Stuart Rutherford, and Orlanda Ruthven

2009. Portfolios of the Poor: How the World’s Poor Live on $2 a Day. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Horst, Heather A. and Erin B. Taylor

2014. The Role of Mobile Phones in the Mediation of Border Crossings: A Study of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, TAJA 25(2): 155-170.

Kusimba, Sibel, Yang Yang, and Natesh V. Chawla

2015. Family Networks of Mobile Money in Kenya, Information Technology in International Development 11(3): 1-21.

Kusimba, Sibel, Harpieth Chaggar, Elizabeth Gross and Gabriel Kunyu

2013. Social Networks of Mobile Money in Kenya, IMTFI Working Paper 1.

Maurer, Bill

2015. How Would You Like to Pay? How Technology is Changing the Future of Money. Duke University Press.

McKinsey

2012. The Triple Transformation: Achieving a Sustainable Business Model, http://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_service/financial%20services/latest%20thinking/reports/the_triple_transformation-achieving_a_sustainable_business_model.ashx

Muller, Patrice, Mette Damgaard, Annabel Litchfield, Mark Lewis, and Julia Hörnle

2011. Consumer Behaviour in a Digital Environment. European Parliament Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy.

Stearns, David L.

2011. Electronic Value Transfer: Origins of the VISA Electronic Payment System. New York, NY: Springer.

Taylor, Erin B. and Heather A. Horst

Forthcoming 2017. Designing Financial Literacy in Haiti. In Design Anthropology: Object Cultures in Transition, edited by Alison J. Clarke. Springer.

Taylor, Erin B. and Heather A. Horst

2014. The Aesthetics of Mobile Money Platforms in Haiti. In Routledge Companion to Mobile Media, edited by G. Goggin and L. Hjorth, pp.462-471. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Taylor, Erin B., Espelencia Baptiste and Heather A. Horst

2011. Mobile Money in Haiti: Potentials and Challenges. IMTFI, University of California Irvine.

Taylor, Erin B. and Heather A. Horst

2013. From Street to Satellite: Mixing Methods to Understand Mobile Money Users. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, London, September 15-19, pp.63-77. https://www.epicpeople.org/from-street-to-satellite-mixing-methods-to-understand-mobile-money-users/

Taylor, Erin B. and Gawain Lynch

2016. Consumer Finance Research Methods Toolkit. IMTFI, University of California Irvine.

World Bank

2015. Massive Drop in Number of Unbanked, says New Report. 15 April, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2015/04/15/massive-drop-in-number-of-unbanked-says-new-report

Xiao, Jing Jian

2008. Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. New York: Springer.