Design ethnography—the term rings with power and potential. Now widely promoted on design studio and agency websites as a core capability, it suggests the melding of design-thinking and interpretive analytical approaches to understanding how people create and make sense of their worlds. But behind the pitch, what are designers doing when they do ethnography? How do they understand the research work they do, their field, their data?

When I ask designers about how they conduct ethnography, I hear things like, “It’s just watching them, but it’s billable.” Or, “Oh the Jane Goodall thing! We kind of do that.” And even, “Is that even a thing anymore? Isn’t that from, like, with islanders?” I’ve finally perfected a neutral, non-judgmental facial expression to present to designers who tell me in interviews that they really don’t have a clue what ethnography is—and these are creatives with ‘design ethnographer’ in their bio, designers who are tasked with conducting ethnographic research for international clients, designers who use the term ‘fieldwork’ in their award submissions and client presentations.

I’ve been struggling with the ways that ethnography as method has been both appropriated and simultaneously rejected by practicing designers throughout the course of my fieldwork in a large international design studio over the past two years. When this study started, my focus was on exploring the relationship between the use of ethnographic methods in the design studio and the resulting practice forms engaged and embodied by designers. But, like all projects that start with a creative brief (and I am a designer by nature through and through—there was a creative brief), further conversations quickly redefined the ‘deliverable’. After facing the resistance designers expressed to defining their ethnographically informed participant observation and interview fieldwork as ‘ethnography’ even when their firm was billing it that way, I refocused attention on the intersections of the institutional logics, rules and tools, and structures of practices at play within the design studio which shape what designers do, how they do it, and who counts as a designer. The findings are pointing the way to how ‘ethnography’ has come to stand in for all manner of sins in the design studio: for the designers I’m hearing from, its most useful quality may be that it defines, makes visible and validates the invisible labour of creative work in a new and useful way. After all, you can’t bill what you can’t see.

What is emerging from the research is that for the community of practice of designers, the methods of qualitative research that I recognize and value come to life only in the client pitch or the creative brief. At first, I found this to be a startling disconnect. But it does not mean that designers are not researchers: instead, the designers I am hearing from are generating insights and analysis in their research work in new ways, developing (as they are wont to do) a new way of solving what can be seen as an old problem.

By refuting the label of ‘ethnography’ within their own practice, designers are telling us clearly that they are doing something new—something essentially ‘designer’ led. I believe that if we listen closely to what they have to say about what they are doing ‘in there’, we can see that by rejecting the limitations of participation and of the field, and of the parameters of our interventions into both culture and practice—designers might be introducing us to an expanded idea of what ethnography can, and even should, include.

As we all know, labels pose limits. But my fieldwork is teaching me that it is not only the labels that the designers adopt for their own work that matter. My own insistence on applying the label ‘ethnographer’ on practicing designers reflects a need to categorize their practice in ways that they themselves are refuting. What they are really doing in there is still becoming clear, but as one creative director described it, “It isn’t all that stuff you keep going on about.”

Designers in this study consistently reject the boundaries with which we as ethnographers have circumscribed the focus, the field and the data that constitute ethnography. But that is not to say that they are not applying methods that we consider to be the rightful territory of ethnography: they just see it (as they see most things) differently. By referring to a hybrid designer-led research approach as ‘testing’, they have created a shorthand for the intersecting of both design thinking and ethnographically informed methods of problem solving.

Sometimes, there is a brilliance to using ‘testing’ as an umbrella term for this intersecting of approaches. It serves to validate and make visible the creative generation process, it acts as a call to action for the designer to pay attention to the lived and embodied experiences of those fellow humans for whom they are designing. But ‘testing’ is also a scapegoat for problems with design process. Your design solution isn’t working for the majority of your uses? Blame ‘testing’: the users we talked to told us that they loved it. Design team can’t fit all the client requirements into the final solution? ‘Testing’ shows that it won’t work, so why are you still complaining?

For the designers who have welcomed me into their studio and their practice, ‘testing’ acts as a veil behind which lie a series of fascinating and unique designer-led research methods. When you ask designers to unpack what research means to them, designers describe something that mixes abductive thinking practices and ethnographic methods. They talk about the way in which they learn to ‘perform’ or embody the role of the user in their work to meet budget limitations. They complain about how they have to learn to recreate what they saw and felt during fieldwork in the studio for repeated analysis by team members. And when asked to describe their own approach, they share how they prioritize fieldwork as a collaborative and interventionist form of ‘making’ over observation and interpretation.

These three approaches, while not entirely antithetical to a contemporary understanding of ethnographic practice, present a challenge to those of us who hold the core tenets of observation, culture and interpretive analysis close to our hearts. If researchers are willing to abandon the spatial boundaries of the field, the temporal boundaries of data collection, and the physical boundaries of participation, then what the hell are they doing in there? Should we still call it ethnography, or does the cloak of ‘testing’ best cover what goes on behind closed doors?

It is easy to say that designer-ethnographers ‘aren’t doing it right’. And it is easy to reduce designer-led research to disaster checks and client appeasement. But I believe that the role of the designer also is to show us the adjacent possible—to connect diverse and disparate ideas and practices together in order to advance our understandings of what could be. If designers, as many have suggested, have stopped building what we think world requires, and have started forecasting those requirements instead, then I believe they are doing the same thing with the boundaries of ethnography itself. And that shift has the potential to inform and expand the boundaries of our methods as well.

When we talk about designers using design ethnography as a form of abductive thinking within their practice, we are talking about a form of problem solving, of logic, of forging connections between unlikely companion thoughts. But the designer too is abductive in this process—a kidnapper of images and ideas stolen from the field and transported back to the studio. Perhaps this is the true role of design ethnography: not just observation, interpretation and analysis but gathering, reconnecting and combining participant’s points of view as active agents in the design process.

Is the designer really an ethnographer? Can one wear a pith helmet and a beret at the same time? Or, with the adapted and hybrid approach to ‘the research’ that designers are nurturing and developing in their studios and agencies, are design-ethnographers in fact something else—something new? I believe that there is much to be shared between my two worlds, and that if we as ethnographers and designers are willing to look critically and closely at what creative workers are really doing in there, we might find that ‘testing’ can be adapted to our practice too.

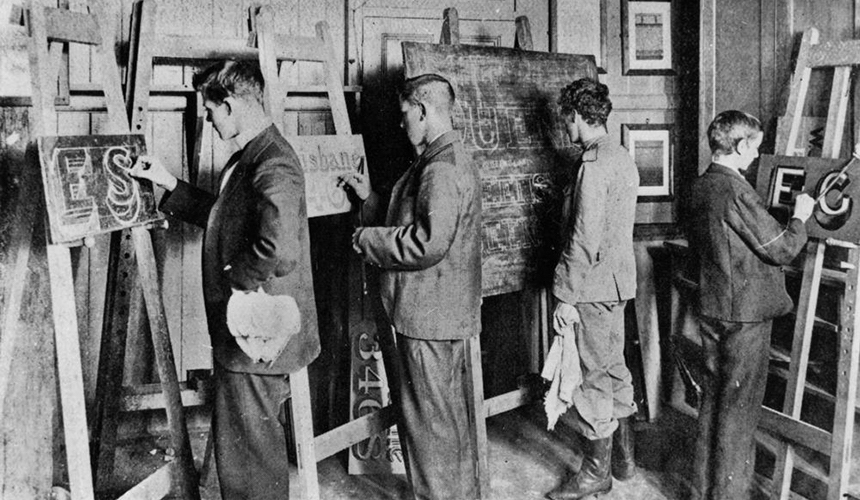

Image: Brisbane Technical College, 1900. Students practicing lettering on blackboards and signboards, via Wikimedia

AnneMarie Dorland is a PhD Candidate at the University of Calgary, where she brings together her background as a designer, brand strategist and ethnographer to explore the intersections of innovation in the creative industries and the work practices of cultural producers. adorland@ucalgary.ca

AnneMarie Dorland is a PhD Candidate at the University of Calgary, where she brings together her background as a designer, brand strategist and ethnographer to explore the intersections of innovation in the creative industries and the work practices of cultural producers. adorland@ucalgary.ca

Related

The QAME of Trans-disciplinary Ethnography: Making Visible Disciplinary Theories of Ethnographic Praxis as Boundary Object, Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall

Valuable Connections: Design Anthropology and Co-creation in Digital Innovation, Mette Gislev Kjaersgaard & Rachel Charlotte Smith

Moments of Disjuncture: The Value of Corporate Ethnography in the Research Industrial Complex, Shaheen Amirebrahimi

Strangers or Kin? Exploring Marketing’s Relationship to Design Ethnography and New Product Development, Sara JS Wilner

0 Comments