This paper proposes a course for ethnography in design that problematizes the implied authenticity of “people out there,” and rather favors a performative worldview where people, things and business opportunities are continuously and reciprocally in the making, and where anthropological analysis is only one competence among others relevant for understanding how this making unfolds. In contrast to perpetuating the “real people” discourse that often masks the analytic work of the anthropologist relegating the role of the ethnographer to that of data collector (Nafus and Anderson 2006), this paper advocates a performative ethnography that relocates the inescapable creative aspects of analysis from the anthropologist’s solitary working office into a collaborative project space. The authors have explored the use of video clips, descriptions and quotes detached from their “real” context, not to claim how it really is out there, but to subject them to a range of diverse competencies, each with different interests in making sense of them. Hereby the realness of the ethnographic fragments lie as much in their ability to prompt meaningful re-interpretations here-and-now as in how precisely they correspond to the imagined real world out there-and-then. We propose that it is precisely the investment of one self and one’s own desires and agendas that lifts an ethnographic field inquiry out of its everydayness and into something of value to further-reaching processes of change and development of attractive alternatives.

INTRODUCTION

In a recent paper, Nafus and Anderson (2006) explored the discourse of “the real people” as an important feature of the epistemic culture of ethnography in industry. They discuss the canonical use of ethnographic photographs and quotations from the field as powerful means of trumping even insightful argumentation, because they purportedly state the realness of the presented ethnographic argument in indisputable terms; in terms of the real: these people are really out there. Situated themselves among engineers, business strategists, and management experts, Nafus and Anderson acknowledge how important the “real people” discourse has been for strategically positioning ethnography as a relevant competence in industry (2006:3). It positions the professionally trained ethnographer as someone who can provide access to the hinterlands of the real people, where products are actually used in authentic everyday life, in ways the client would never have imagined. The problem with this discourse (besides that it does not correspond with the epistemological assumptions of many ethnographers, who are usually reluctant to refer to “the real” without the quotation marks, and who usually consider themselves and their clients as real as their informants) is that it leaves the analytical work of the ethnographer invisible, and thereby making ethnography look like mere data collection.

Already in 1994 Robert Anderson from the Rank Xerox Research Center in Cambridge responded to the ongoing discussions about the value of ethnography in systems design. He argued that many in the systems world have seen ethnography only as “information gathering and have missed the critical importance of representation” (Anderson 1994:160). While getting to know users and their knowledge and practices are important tasks for design, “you do not need ethnography to do that; just minimal competency in interactive skills and, a willingness to spend time, and a fair amount of patience” (Anderson 1994:155).

Both of these papers, written ten years apart, raise the question of whether the ‘real people’ refrain, and the representationalist knowledge practices it prefigures, will continue to characterize ethnography in industry. Like all three of these authors, we believe there is more value to be drawn from anthropology than data collection. In the present paper, we therefore take the invitation to chart an alternative path than that of exaggerating the real people refrain. We propose a course for ethnography in design that problematizes the implied authenticity of “people out there,” and rather favors a performative worldview where people, things and business opportunities are continuously and reciprocally in the making, and where anthropological analysis is only one competence among others relevant for understanding how this making unfolds.

Our experiences are drawn from research and design projects in collaboration with partners in industry and public institutions. They include ethnographic engagements with the fields of interaction design, system development, architecture, education, and public policy, and generally belong to design-oriented areas of industry. The projects have been carried out in the Scandinavian tradition of Participatory Design and accordingly our ethnographic engagement with users has aimed more at eliciting their active participation in the projects, than at generating knowledge about them, as objects of study.

Let us start out somewhat paradigmatic: we believe the world is in a continual process of becoming through our engagement with it, and the user is not authentically “out there” to be discovered independently of our interest in the discovery. The user emerges somewhere in the meeting between our ethnographic search for “real people,” the practice of the particular participants in our study, and the projected interest in them posed by project stakeholders as possible new areas of use.

When Nafus and Anderson claim that “…the stand-alone quote is in fact the truth that conceals that there is none. It points to a seemingly external context that is being constructed inside the corporate meeting room,” (2006:11) we could not agree more. However, this creative work of imagination and construction that goes on in the corporate meeting room when clients are confronted with fragments of the surprising and strange ways of the users need not be read as a regrettable delusion. The world-constructing practice that can be prompted by an ethnographic stand-alone quote, image or video clip that point outside the meeting room is precisely what we are after. It has not led us to reduce our use of these rhetoric devices that purportedly connect us to the “real world”. In fact, we work out of a research tradition that excels in stand-alone quotations and context-free video clips (e.g. Buur and Søndergaard 2000). Let us explain and demonstrate how techniques that are widely used to establish the ethnographer’s authority of knowing what is “really out there”, can be used in more playful performances of realities in the plural.

Rather than lament that the anthropological analysis is bracketed off in the excitement over quotes and images, we propose a performative ethnography in design that relocates the inescapable creative aspects of analysis from the anthropologist’s solitary working office into a collaborative project space. We have used video clips, descriptions and quotes detached from their “real” context, not to claim how it really is out there, but to subject them to a range of diverse competencies, each with different interests in making sense of them. Hereby the realness of the ethnographic fragments lie as much in their ability to prompt meaningful re-interpretations here-and-now as in how precisely they correspond to the imagined real world out there-and-then.

The motivation for this paper and the work that lies behind it is a reaction against overly realist ideas of what ethnography may do in industry. To explore how performativity may provide us an alternative path from the “real people” refrain, we will begin with clarifying what kinds of performativity we are concerned with, and then proceed to present two particular examples of performative ethnographic practices in design.

TWO STRANDS OF PERFORMATIVITY

In distancing our ethnographic practice from providing the facts, or acting as truth witnesses for example in design negotiations whether or not a specific product feature is relevant for the real user, we will follow two strands of performativity: first, a broad performative ontology to conceptualize the practice we as ethnographers inquire into as an ever-evolving and unsettled becoming that resists reification in, for example, personas or segments; and second, performance theory from the performing arts to better understand the social interactions that are involved in playful explorations of how the world could be thought of when ethnographic material is presented to industrial audiences with diverse interests.

Ontological Performativity

Looking at performativity in the broadest sense of the word implies that everything continually comes into being through its social and material performance. Such a perspective is employed to capture the process whereby phenomena are produced or reproduced through their particular performance. In How To Do Things with Words (1962) John Austin presented the concept of the performative utterance. It was a reaction to the logical positivist focus on the truthfulness and verifiability of statements. As a category of utterances without truth-value, the performative does not describe but acts on the world, hence the title of the book. In other words, by the utterance of the word, the act is performed. Austin also launched the more encompassing idea that all utterances are in fact performative: they dosomething.

Since Austin’s pioneering work with performative utterances, post-structuralism has given rise to fundamental questions to the distinction of categories, beyond linguistics. Movements in science and technology studies, actor-network theory, feminist theory, cultural studies, social and cultural anthropology have developed a general analytical understanding that distinctions are not given in the order of things, but rather seen as outcomes or effects. With the notion of relational ontologies, the fundamentally semiotic insight that entities take their form and acquire their attributes as a result of their relations with other entities is applied to anything. In light of the notion of performativity, the discussion of what is really out there is abandoned in favor of a discussion of how things continually become what they are in and through their performed relations with other things. Since entities have no inherent qualities, the question is how, then, do things become what they are?

Performative ontology, i.e., that things become what they are through their performance, has been developed especially within Science and Technology Studies. Pickering, for example, suggested a “performative idiom” for the study of scientific practice (1995) and thereby articulated a new attention to the production of scientific facts. Similarly to what the performative idiom has done to understand the production of scientific facts, we suggest can be done to understand the production of designerly facts such as “the users and their practice” or “the client and their resources.” These are entities that appear very real, yet they come into being through meticulous processes of performance. From within feminist theory, Butler has shown how gender works as a performative—constituting the act that it purportedly describes (1997). While Butler focused on the repetitive nature of gender performances, here we are more concerned with the possibility of actively inducing change as an emergence among actors.

The post-structuralist preoccupation with how things continually become what they are suggests the transformative power of performance. An important consequence of performativity is “that everything is uncertain and reversible, at least in principle” (Law 1999:4). While it has been demonstrated many times that it matters how things become as they are performed, it is still an open question how this insight may be brought to bear on our understanding and practice of ethnography in design. Could we improve the efficacy of the design process by conceiving of it as a performance? What resources do we as ethnographers have available to perform the social and technological interactions of the future? With these questions we take ontological performativity to be valuable not only as a means to analytically understand ethnographically experienced practice, but just as importantly as a relevant contribution to a reflexive design anthropological practice. To pro-actively embrace the idea that everything in principle is uncertain and reversible implies, in terms of ethnography in design, encouragement to consider the design process as a conscious effort to enact particular modes of reality and people’s concerns about them.

The relational ontologies of use and design imply that the one does not come before the other; rather, they necessarily constitute each other. There is nothing paradoxical in exploring the possibilities of use through the practice of design. It is impossible to think about design without already implying some sort of use, and vice versa. This prompts us as design oriented anthropologists to create opportunities where use practices can be performed differently; where they can be explored in terms of design possibilities, and vice versa.

Confined Dramaturgical Performativity

The anthropology of performance has to a large extent evolved from the study of rituals and symbols. Let us begin with ritual as it has been anthropologically conceived. As early as 1909, Van Gennep published his classic study of Rites of Passage (Gennep 1960), i.e. ritualized changes of social or cultural state, as for example becoming human, becoming adult or becoming married. Van Gennep described the general structure of initiation rites as following three ritual stages: that of separation (the person to be initiated is detached from society), that of transition or liminality (the state of the person is ambiguous while approaching the new state and having left the old) and that of reincorporation (the person is re-introduced to society in the new state). Victor Turner later expanded these ideas, focusing especially on the liminal period, which he also identified in other types of rituals than rites of passage. He was concerned with the transition as a process, as a becoming and transformation. One of Turner’s central points was that the ritual suspension of normal order is a necessary step for achieving the desired changes of state. Turner described the temporary liminal state of the indefinable transitional being as “betwixt and between,” in the sense that it is at once no longer classified (for example as a boy) and not yet classified (as a man) (Turner 1996).

The borderline between the anthropology of ritual and performance theory has since been famously traveled and conceptualized by Richard Schechner in part fueled by Turner. Schechner used insights from the analysis of ritual to experiment with actual dramaturgical performances and thereby challenged and developed the established notions of stage, actor, script and audience. Of particular interest here, are Schechners observations of how the act of performing can transform both the actor and the audience. The act does not simply represent another mode of reality; it plays with modes of reality. Through various techniques for setting the scene, prompting improvisation, and for inviting audience participation, Schechner has been a major influence on both the theory and practice of the performing arts.

Employing The Two Strands Of Performativity In Design

The two ways of employing “the performative” outlined above stem from different strands of discursive practices. One of the differences between the confined dramaturgical sense (e.g. Schechner 1988) and the all-encompassing ontological sense (e.g. Barad 2003) lies in whether or not transformation and creation through performance necessarily happens all the time or mostly in special occasions arranged for social display. One of the virtues of the ontological performativity is that it forces us to extend the analysis from the explicitly declared design activities to include also the broader relations implied by constructing for example an image of “the creative user”. In design workshops, the designed artifact is not the only thing being performed. The people who have accepted to engage in the project as “themselves,” as possible end-users, constantly become what they are through their personal and professional activities, decisions and relationships. In this vein, the engagement in a research and design project is yet another opportunity for the participants to re-invent themselves and their professional or personal practice. Furthermore, technologies cannot in any simple way be defined by their mere functional properties; technologies become what they are through the particular ways they are contextualized in various changing patterns of use and abuse. In general the ontological performativity has proven productive for the challenging and questioning of apparent identities, claims to authenticity and acts of essentialization. However, the general metaphysical assumption or conviction that all things become through and only through performance entails a risk of trivializing the conscious act of playing with possibilities through performance.

If everything is performative, then it is nothing special to state that particular collaborative design events work by performing that which they want to create. Our understanding of collaborative design is in line with Binder’s conception of the dynamics of participatory design: that it works by performing that which it wants to create (1995). But in light of ontological performativity, this conception may seem trivial, because everything by definition is created through its performance. If everything is enacted, then facilitating a particular user’s enactment of a future scenario merely states the obvious.

Consider a design-oriented ethnographer who has carried out field visits, prepared design materials, and staged a design workshop with relevant partners. She may intensely want the small future scenarios to become something more steadily materialized: a working technology that people will actually use. When she is sometimes unable to move other entities and make things happen, despite the presence of all the ingredients that make up a usual actor-network chain of translations: a special room, furniture arranged for action, people with resourceful development organizations behind them, practice made partly controllable through inscriptions in text and image, etc. it almost amounts to an insult to her efforts to ask the prototypical analytical question of ontological performativity “how are things performed into being?” because the empirical problem is precisely the opposite: “why was this thing not performed into being?”

To approach the intricacies of exploring ethnographic field material while at the same time looking for possibilities for it to become something else, we turn to performance theory in the more confined sense, where performances constitute a special class of events consciously arranged to achieve specific ends. A central characteristic of theatrical performance theory as opposed to the post-structuralist understanding of performance as an ontological condition is its concern with the subjunctive: the famous what if.

THE DESIGN EVENT AS A RITUAL PERFORMANCE

Let us suggest an understanding of collaborative design events as a kind of dramaturgical performance. To qualify this suggestion we shall first point to a classic connection between theatre and the everyday.

Everyday Dramas

Anthropology, in particular, has treated the actual lived practices of people through a performative perspective, showing how humans are always involved in constructing and staging our identities. This, of course, has not been to suggest that practices are in any way fake, but rather that we all enact our personal and social realities on a day-to-day basis. From within anthropology, Turner eminently showed how these performances of the everyday took the form of rituals and social dramas.

While performativity in the post-structuralist sense constitutes an entire ontology, or more precisely ontologies, Erving Goffman used drama and performance as a metaphor for social life. Since Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1958) the performances inherent in everyday life have been a common focus for the social sciences in general. Goffman was concerned with the dramatization of the individual, and demonstrated how people in everyday interactions maintain or establish a given definition of the situation. The achievement of the collective definition of a given situation is dependent upon the participants investing their image of themselves—their face—in the performed situation. This collaborative act of maintaining images of self, e.g. to not lose face, Goffman referred to as facework. In the present context of ethnography and collaborative design, the investment of the image of self should be taken in its broad sense including professional skill, technological competence and preferences, organizational resources, personal values, concerns, and career goals; in other words, it is not restricted to personal identities. In Goffman’s view, this kind of interaction takes place in a wide variety of situations; everything is more or less improvisationally staged in response to a social script and with a sense of an audience providing feedback in one form or another.

There is a transformative potential in the encounter between script and action, insofar that situations can actively be established where alternative definitions of situations are collaboratively produced. There is, at least in principle, the possibility of achieving a durability that extends alternative definitions of a situation beyond its immediate performance.

Design Rituals

Collaborative design workshops often work by playfully performing things into being that are still beyond the point where they can be fully articulated. Let us consider this in dramaturgical terms. Through rehearsals, improvizations and the inscription of imaginary meanings onto props the design event, like theater, institutionalizes the liminal space. Here the dominant mode is the subjunctive, the what-if. The process of producing a future scenario is guided by a similar logic to that of a theatrical rehearsal: trying out different kinds of user interactions with technology to see if they appear to be attractive performances of the world. Referring to theatre Schechner stated similarly: “It is during workshop-rehearsals that the “if” is used as a way of researching the physical environment, the affects, the relationships—everything that will sooner or later be fixed in the performance text.” (Schechner 1985: 102)

The design workshop as a whole is enacted in ways similar to the rite of passage: as a momentary suspension of the everyday order, as betwixt and between, in order to prepare the subject for transformation. In the design workshop it is not a social individual that is to undergo transformation—it is practice as it meets technological artifacts. Practice and technology are thus separated from their normal surroundings, drawn into a liminal space and time where they can be symbolically “broken down” as Turner expressed it, in order to facilitate their transition to a new state.

A central challenge for performative ethnography in collaborative design processes is to avoid contributing to reifications of the presented ethnographic material. We have sought to maintain an openness towards mutations of the ethnographic material and let it become part of the continuous unfoldings of practice, rather than testimonies of the past. The goal we set for our efforts in between ethnography and design is thus to create a design space that is at once open for exploring the everyday practice of a given setting or group of people, and at the same time to bring about a lively sense of what it might become in light of the given resources.

Let us consider the design workshop a performative event. While we are quite sure the participants in our actual design projects do not see themselves as performers in any theatrical or ritual way, we would like to push the comparison. The anthropological gaze upon the practice of collaborative design renders visible the magico-ritual character in the production of the New. There is a fit between what the design workshop and the enactment of future scenarios encode, to what theories of performance and ritual are attempting to analyze.

While we look at design events as performances and apply Schechner’s concept thereof, this is not to say that they are about entertainment. On the contrary, they are explicitly about driving design processes forward by generating new ideas and producing useful concepts for new artifacts. As performances, the design events seek to change people and things, technology and practice through the witnessed enactments of what may be.

Performance theory and practice have moved steadily from a concern with classic theatre towards employing performance as a method of cultural reflection and change. This movement is for example seen within the branch of performance ethnography where performance is framed as “a critical reflective and refractive lens to view the human condition and a form of reflexive agency that initiates action” (Alexander 2005:412). What we are after here is the intent of allowing the participants in, and audience of, a particular performance the opportunity to come to know culture differently, and seek the openings for change that sometimes emerge from this. Although performance ethnography is more often associated with social movements than with design explorations, Alexander’s description of its virtues is relevant for the design anthropological practice outlined here: “The power and potential of performance ethnography resides in the empathic and embodied engagement of other ways of knowing that heightens the possibility of acting upon the humanistic impulse to transform the world” (Alexander 2005:412).

In light of performance theory the problem of how design workshops seem to encapsulate a small part of the future now seem less paradoxical or controversial. In some rituals the actualization is the making present of a past time or event. The ritual makes the myth present by showing it as happening, here and now. Design workshops in their varieties depend upon performative transformations of time and space. However incomplete or temporary the transformations may be, they enact a specific “there and then” in this particular “here and now”. This, of course, is not to say that some future reality is here, but it playfully suggests that if it appears attractive and possible to the present audience, the future might be characterized by this mode of reality.

TWO CASES OF PERFORMANCE

As an introduction to the two cases of performance presented below, let us broaden the focus on design from a singular event secluded in its intention to generate design concepts, to a variety of project related activities whether more representative of analysis, brainstorming, or building. Design takes place not only in formal events such as a collaborative workshop, or in formal surroundings such as a design studio, but in the interstices of everyday life, whenever we realize our practical and imaginative capacity to transform the circumstances of our lives into scenarios partly of our own choosing. The design event does, however, as we will turn to below, present a unique opportunity to mobilize at once resources and concerns that would otherwise remain more distantly related.

The problem of establishing a space that is out-of-the-ordinary, in order to view the well known in a new light is ubiquitous for design. As we have seen from Clark’s work on participatory design, a liminal space has to be established across a wide spectrum of stakeholders throughout the project space: in the informal talk in the corridors as well as in the more consciously staged design activities (Clark 2007). To get started thinking and talking about the new, a liminal space must be established. Here we focus on examples of social arrangements for how they are arranged to appreciate and induce a liminal state for the various participants. That is, how are the participants not only found to be betwixt and between various roles, on the one hand, and how are the participants encouraged through a staging of performance, to playfully explore what could be possible.

Re-Enacting maintenance work

The following situation took place at the Danish company Thy:Data which develops software solutions in partnership with Microsoft Dynamics.

Carsten (senior software developer acting as machine operator Jeanette): “I arrive at work, take my tablet PC here by the black-box machine and log in as Jeanette… I press “arriving”, and it is then registered that I have arrived at work. I press “start task” here on my task and start up my machine and take care of the belt with black machines… no, (corrects himself) black boxes… And it works well… (pause) A box tips over!”

(From video of workshop, November 2005)

Figure 1. Software developer acting as a machine operator in a design workshop.

As can be seen from the image, the software developer is not actually operating a machine and a conveyor belt on the shop floor of a snack manufacturing facility. He is in a meeting room and with the machine and the belt represented by a line of black cardboard boxes on a regular table he pretends to be in the situation of a machine operator. While he carries out the bodily gestures of operating such a machine, he also handles a piece of white foam that he pretends is a tablet PC running an imaginary new software application. In the course of acting out the specific interactions with the new application the software developer sometimes hesitates, because he realizes that the paper interface on the white foam does not provide the relevant options for the situation. During the performance of this scenario the software developer is confronted in very practical terms with his own design. The audience, or in this case the video camera and the expected audience, raise the demand on the performer to act competently. And while the developer can be excused for not knowing exactly how to operate production machinery, the expectations are higher that he can make sense of the interface that he has previously conceived for the IT system. The senior developer and the lead program manager who are the primary forces in this performance work hard to make the mocked-up system interface match the specific situation—or do facework as Goffman would term it—to achieve a collective definition of this meeting room situation as if it were a desirable situation at a factory shop floor.

Obviously, we have not just walked up to any senior software developer and asked him to dress up and begin to push imaginary buttons on a piece of foam. A lot of work preceded and enabled this performance. The situation played out is actually a re-enactment of a situation that took place during our initial ethnographic fieldwork on a particular factory shop floor, that of KiMs, a Danish snack manufacturer. Our first presentation of this field material to the client audience had been a deliberately incomplete account abundant with fragmentary quotes, images and videos. When we think of these ethnographic fragments as design materials in light of performativity, video clips from the field are performative utterances, rather than representations as such. Alongside the technological components and foam shapes in the design workshop they do not represent anything as much as they point to related entities, and their main quality lies in this direction of other’s attention. The statements about other entities implied by the use of design materials are thus to be considered not as speech acts, but as object acts. In the specific case of video clips, we may usefully employ the term image acts introduced by Blackwell (1998) as a paraphrase of Austin’s speech acts.

As Nafus and Anderson observe, the ethnographic fragments point to “a seemingly external context that is being constructed inside the corporate meeting room” (2006:11). – Not entirely inside the meeting room we would have to add. Rather, the ethnographic reality is continuously being constructed in the complex relationship between observed and observer. Let us consider this relational construction as a double movement, where the seemingly external context (that of maintenance work at KiMs) is not granted a higher degree of reality than the corporate meeting room. By staging a re-enactment of the presented ethnographic fragments it is in fact possible to involve highly competent non-anthropological stakeholders in testing out how this foreign situation could be understood. This amounts to inviting a plurality of competences into the construction of analytical hypotheses, instead of insisting on the anthropologist’s privileged position for defining what the world really is.

Figure 2. Maintenance work enacted in situ by service technicians and subsequently re-enacted by software professionals in a meeting room. It is clearly not the same situation, yet not entirely different situations either.

Performing collaborative analysis

In our second example, designers and researchers are enrolled into a collaborative analysis session featuring ethnographic material during a design workshop. The session involves a first attempt to make sense of a complex field. In the project, Design for Cultural Pluralism (CUPL), the university’s industrial design department, in collaboration with the local Swedish municipality, sought to explore how design could support cultural integration among middle school-aged children from non-Swedish descent during their school and afterschool activities.

At this stage of the project, the team began understanding how the broad issue of cultural integration became visible in the lives of middle school students—when and how culture was considered advantageous or problematic by children and the adults supervising their activities. After the initial fieldwork among the activities of young people (i.e. in a youth center, classroom, library and sports club), the team arranged a half-day design workshop with scholars from the university’s Informatics department and Department of Interactive Media and Learning. The purpose of the activity was three-fold: to introduce the design team to an analytic stance toward their field experiences, to expose the team to disparate perspectives on the material, and to begin exploring potential technological possibilities.

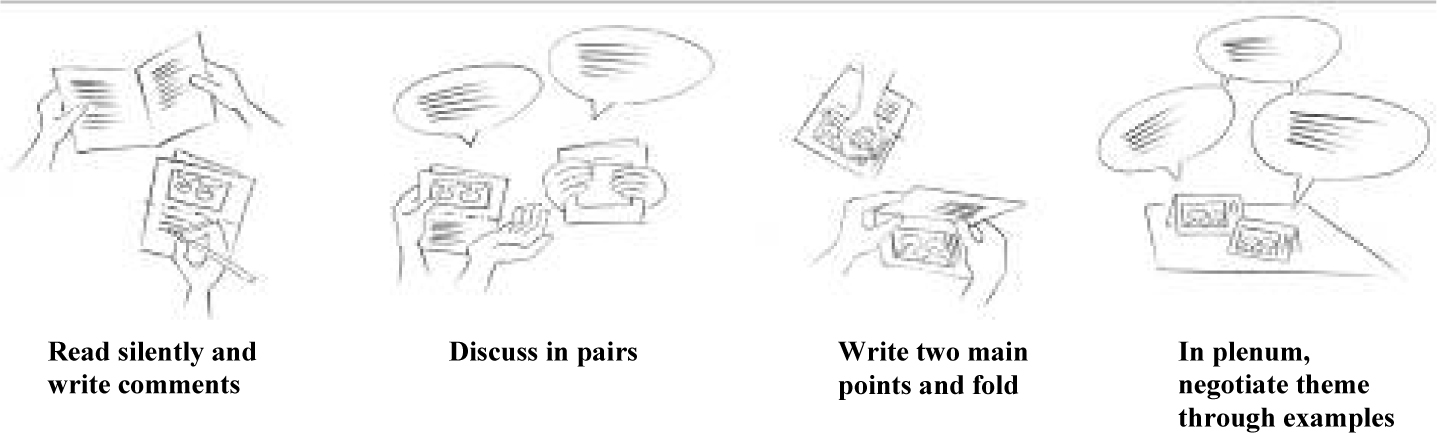

As can be seen in the text below, the field accounts described not only the research participants, but also the research encounter between the design team and the participants. During the workshop, the six participants were asked to engage in a variety of tasks in relation to the ethnographic accounts. The tasks were sequenced so that the participants would begin describing their individual perspectives, discuss in pairs, and ultimately introduce them to the group in plenum as a witnessed performance.

The three pairs of participants sat around a table with three large pieces of paper on the table between them like a three-part game board. Each pair had four or five text cards in their hands—each card started as a one-page description of field material and was folded into an a-frame card that could stand on its own (see diagram below). The facilitator asked each pair to introduce one of their cards to the group by simultaneously describing it and placing it on one of the game boards by either adding it to a pre-existing category, identified by a group before them, or to purpose a new category for the representation.

Figure 3. A sequencing of reading, writing, and discussing, supported by the folding of a sheet of paper turned into a freestanding text piece with multiple authors.

It is now Mia and Erika’s turn to introduce one of their cards. Mia places the music room incidentcard on the negotiating identitycategory. Mia gives an overview of the incident described in the text and the reasons she feels it relates to the category:

Mia I mean, I think this could go there in a way too, the Music Room Incident. It was Brendon and another guy who was in the music room trying to play an instrument. I think that guy was seventeen and all of a sudden this gang of kids, young kids, twelve to fourteen, rushed in and kinda tried to cover the drums and the microphone and tried to, just being annoying. And then finally they left and this guy Dan said “Damn immigrant kids” and kind of looked for Brendon for approval, “do you agree? Is this ok?” I thought this was really interesting too ’cause this ethnicity or belonging as a filter of understanding because if they weren’t from another origin, they would be just an annoying gang maybe. It would be something else. It’s just a group mentality where, kind of young and annoying, wanna destroy, want attention, but now this explanation was ethnicity. And this Dan is also, I mean, Brendon was not a Swede. In a way so its like they can take different roles because they were like us and them so it’s in a way about negotiation of, like, in this case I am very Swede, and in another way I’m maybe not and Brendon was all of a sudden a Swede kind of like Dan.

Erika Or higher up on immigrant scale. There’s a hierarchy.

Mia Yeah, that’s also negotiation. Like, “who is the one who has the right to be there? Who has the right to have that?”

Here Mia used the encounter between the children and the ethnographer in the “music room incident” as part of the analysis. Yet, by looking back the comments she first wrote on the card before her conversations with partner Erika, it was Mia who had actually written the point about the immigrant scale. Yet when formulating the explanation for the group, Erika stated the point almost as a cue to Mia, spurring her on in her presentation of the point.

Preceding this move, when Mia first read the account in silence, she had written on the a-frame card two points she found most interesting:

- Interesting to question what the ethnicity question brings to the understanding of the situation. Would have been a different reaction to the same behavior if they were “Swedes.” Did they want to be seen or just destroy?

- Example of hierarchy between different groups

Figure 4. Workshop participants discuss, read and move pieces of tangible text.

Whereas only Mia had read the account initially, it was through this highly staged sequence of activist that Erika was able to support her assessment suggesting that there is a “hierarchy of immigrants,” a point that Mia had initially written in her comments of the account and later discussed with Erika. This suggests it is a point that Mia conveyed to Erika during their discussion/rehearsal, but Erika then raised supportively in performance to support Mia in front of the larger group. In this case, Mia described the interaction between the boy and the researcher highlighting his role in the incident merely as content to be explored. The researcher’s participation in the incident in relation to the Swedish boy and other “non-Swedish” children demonstrates to Mia the notion of a hierarchy of “different groups” and their elasticity.

The event provided a sequencing of actions for three strangers from different fields and three design researchers to quickly engage with material through experimenting playfully with ways of looking upon the material and describing with its contents. The description of the music room incident using the ethnographer’s biography demonstrates two levels of triggering performances others to perform. The incompleteness of the accounts or the seemingly raw state of the accounts, namely, void of explicit analysis, combined with the format of the paper and activities, shifts the focus from merely seeking the most accurate facts to share, to allowing the participants to loosely, yet seriously, speculate on ways of looking at the accounts.

The Suspension Of Disbelief

To induce liminality requires that participants are willing to explore the “what if” often requiring a symbolic “sanctioning off” of ordinary accountability of everyday activities. As one of the reviewers of this paper has noted, and thereby giving voice to numerous other skeptics over the years, from corporate clients to ethnographic colleagues: “I find it difficult to imagine just how this approach would work such that audiences wouldn’t find it somewhere between amusing and a waste of their time” (anonymous reviewer). Or critics will state that we could not make their customers dress up and start acting out, because they belong to a different class of executives. While to an outside observer the playfulness and peculiarity of liminal activities may not appear serious, we follow Schechner and Turner in maintaining that experimental rehearsals have serious and necessary implications for subsequent performances. A “play frame,” a “workshop frame,” or a “theatre frame,” often entail the non-threatening justification people may need to feel compelled to explore otherwise risky ideas and behavior.

Part and parcel to creating liminal spaces for design performances, is the need to indoctrinate skeptics through a range of rhetoric devices and continuously illuminating the value of their participation in such events. To this range count for example the realist impression that these ethnographic representations account for “real people”, as well as sheer group pressure to perform well in front of other participants. The transformation through the ritual often includes a surprise in the power of what initially seemed amusing or useless activities. It is therefore a provocative activity to engage skeptical participants and staging such awakenings.

Despite these obvious challenges for this kind of work, we would like to push the argument further and show how we have succeeded in establishing liminal spaces that are radically out-of-the-ordinary, and thereby enabling participants to reshuffle realities in ways that were otherwise not possible.

CONCLUSION

On the grounds laid out here, it makes little sense to uphold a clear working division of labor in producing appropriate technological interactions where the role of ethnographers is to map real and existing practices, and the role of designers is to conceive an attractive and artificial future practice. Further, the perception of design as bridging an imagined gap between “real existing practice” (the business of ethnographers) and “an imagined future” (the business of designers) is likewise rendered less fruitful. A conservative ethnographer may object that ethnography is about understanding that which is already there, and not about changing it or inventing new practices. This objection, however, predicated on a realist ontology, is assuming a priori a categorical distinction between the present and the future. Ontological performativity implies that everything is new, insofar that it is the latest unfolding of practice. The gap between the existing and the future is precisely what is being constructed through the process of design, not the other way around.

It is a frustrating fact that we as ethnographers often cannot recognize our foundational assumptions about ethnography in the way our services are conceived by clients who want “the real people” refrain. To make the most of the present challenges and opportunities for anthropology as it meets design and other interventionist fields in industry, we have consciously adopted an eclectic and experimental approach that liberally borrows and bends concepts across disciplinary boundaries. But it has enabled us to formulate guiding questions for our research in the borderland between anthropology and design: What if airy ideas about better practices and wishful thinking about more interesting technological experiences were given some sort of tangible form? How would they play out among the subjects of the study, if they were invited to partake in the experiment? What bodily resources could be drawn upon, if contingencies were explicitly staged and embodied as conditioning only possible realities among others? How could the creative potential residing within the subjects’ skill and practice be realized for purposes that reach beyond the individual? We have found performance theory powerful in understanding and engaging the transformative potential of specific performances such as enacted future scenarios. With the partly improvised future scenario as it was enacted by the senior software developer, we have shown how evoking the embodied habitus of skilled participants in the performance of a future scenario goes beyond the practice of describing and knowing the participant (whether that be a software developer as in this case or a service technicians as in the events that preceded the one recounted here). The participant’s embodied habitus was brought to bear in performances of the doing of the body, imitating an idea of the future through the real, and thus leading to glimpses of prior incidents, concerns and situations interspersed with alternative possibilities prompted by the particular present situation. The staging of partly improvised future scenarios creates a state of limbo with regard to the ontological status of the performance. It is not in any strict sense an occasion for observing how maintenance work is regularly carried out; neither for a controlled test of a new product candidate. Yet it is both a continuation of the ethnographic field study in that it yields new insights about the conditions of use practice and it is a continuation of the generative design work in that it evokes new ideas for the concept design. The act of performance fosters identification between the dissimilar ontologies of the here and now and the there and then without reducing them to sameness. The unsettled status of the activity works to create a space of grounded possibility, where the skilled practitioner is included in the effort to bring about design ideas that are rooted in his/her practice.

Although we are accustomed to representations that locate “the real” in terms of mimesis, the ethnographic material brought from a site of use into a design workshop in the form of fragments do not only play out modes of use, they play with modes, leaving actions hanging and unfinished; they do not reflect use practice as much as they present ideas about use practice. When use practices are made present to various designers in text or video fragments, these fragments in turn become the screen to which they project their interests, fantasies and desires. Hereby the ethnographic fragments become the occasion for articulating a more complex and unsettled image of use and design practice, than a singular and coherent account focusing entirely on a confined context of use would capture. The value thus resides in the participants’ willingness and ability to rehearse and perform their own interests into the respective fragments of an ethnographic reality.

Let us present, here towards the end, a perhaps slightly provocative idea. In order to move beyond the “real people refrain”, we may need to rather suspend the categorical openness of the ethnographic inquiry and the perpetuation of the ideal notion of longer-is-better ethnography. We propose that it is precisely the investment of one self and one’s own desires and agendas that lifts an ethnographic field inquiry out of its everydayness and into something of value to further-reaching processes of change and development of attractive alternatives. From fieldwork, the emergence of patterns, possibilities and the widespread acknowledgement that things could be different are dependent on motivated search. If we acknowledge that we want something from our ethnographic accounts, something that usually exceeds mere documentation, we need to qualify the open-endedness of our inquiries. It is only so open.

Joachim Halse is currently assistant professor at the Danish Design School in Copenhagen.

Brendon Clark is a Design Researcher, Mads Clausen Institute, University of Southern Denmark.

REFERENCES CITED

Alexander, B. K.

2005 Performance Ethnography: The reenacting and Inciting of Culture. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln. London, Sage Publications.

Anderson, R.

1994 “Representations and Requirements: The Value of Ethnography in System Design.” Human-Computer Interaction 9: 151-182.

Austin, J. L.

1962 How to Do Things with Words. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Barad, K.

2003 “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28(3): 801-831.

Binder, T.

1995 “Designing for work place learning.” AI & Society9(2-3): 218-243.

Blackwell, L.

1998 “Image Acts.” American Anthropologist100(1): 22-32.

Butler, J.

1997 Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. London, Routledge.

Buur, J. and A. Søndergaard

2000 Video Card Game: An augmented environment for User Centred Design discussions. DARE 2000 on Designing augmented reality environments.

Clark, B.

2007 Design as Sociopolitical Navigation: a performative Framework for Action-Oriented Design. Mads Clausen Institute. Sønderborg, University of Southern Denmark. PhD dissertation.

Gennep, A. v.

1960 The Rites of Passage. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Goffman, E.

1958 The presentation of self in everyday life. Edinburgh, University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre.

Law, J.

1999 After ANT: complexity, naming and topology. Actor network theory and after. J. Law and J. Hassard, eds. Oxford, Blackwell Publishers: 256 s.

Nafus, D. and K. Anderson

2006 The Real Problem: Rhetorics of Knowing in Corporate Ethnographic Research. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference, American Anthropological Association.

Pickering, A.

1995 The Mangle of Practice: Time, Agency, and Science. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Schechner, R.

1985 Between Theater and Anthropology. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Schechner, R.

1988 Performance Theory. New York, Routledge.

Turner, V.

1996 Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage. Sosialantropologiske Grunntekster. T. H. Eriksen. Oslo, Norway, Ad Notam Gyldendal: 509-523.