As an introductory set of remarks for the theory session, this short paper sets up some issues facing both the field of ethnography applied in industry and those who undertake theoretical work in the field. The author proposes some simple dimensions for discussion: how we might consider work in industry a definite and distinct location for theory work; the nature of relationships with key interlocutors that are fundamental to working in industry; and finally, the role, opportunity, and responsibility that theory work might have going forward.

Every conversation has a beginning. A first voice that says, “I’m here.” In saying “I’m here”, that voice invites, recognizes or imagines its interlocutor. And in saying, “I’m here,´ “here” becomes a place. A theory paper is one of those first voices. Situating itself. Taking a position. Beginning a conversation.

It is one thing to walk into a crowded space, full of friends or family, and strike up a conversation. You are sure of getting a hearing, you know which gambits of the insider to play, and if you leave, you know that your ability to return is assumed. It is another thing entirely to walk—through a doorway showing few signs of previous use—into a featureless dark and speak with clarity and confidence. To say “I’m here,” without an idea of who or what might be listening, nor what those listeners might say or do in response. Starting a conversation that way requires some faith, some fortitude, and some vision.

The conversations we’ll start here this morning are especially important because where “here” is is, to be generous, less than well defined. I doubt that I’ve ever been in a room with as many other people whose mothers don’t really know what they do. Despite the amount of theory-based work that gets presented at the AAAs, SfAA, or 4S on the one hand and CSCW, SIGCHI, UbiComp or PDC on the other, I don’t think that there has ever been a dedicated theory session on ethnographic work in industry before. These are, I think, new conversations to have.

At the risk of overextending it, I’d like to take just a few minutes to abuse this metaphor a bit further. If these papers represent some of the first voices to say, “I’m here,” which I think they do, and do well, a few critical questions come to mind:

- Where’s “here”?

- Who else is in this conversation?

- And what makes theory such an important thing to converse about anyway?

So first,

WHERE IS “HERE”?

I think it is unlikely that anyone here would have trouble saying in what discipline he or she were trained. Or even in what ‘tradition’ that training might have more particularly defined itself. That said, it is also almost a given that most of us work not squarely in those original disciplines or traditions, but rather in interdisciplinary gaps and in practical spaces that reflect something of a mismatch between disciplines and organizational definitions: anthropology and technology, or culture theory and computer science, or any of those and design or marketing or strategy.

This would not be so bad if we were—as both individuals and organizations—knowingly engaged in the development and definition of a new hybrid field, something along the lines of one of the ‘ur models’ in the sociology of science: the emergence of molecular biology from the collision of biology and chemistry described by R K Merton in the “Cold Springs Harbor” paper. A kind of consensual domain formation, through the integration and re-grounding of disparate practices engaged with common problems.

But that doesn’t seem to apply here. Terms like “applied anthropology” or worse, “user research” don’t seem at all to have the gravitas of “culture studies” or “developmental psychology” or even “comparative vertebrate anatomy,” yet alone speak to something more richly formulated than the application of an approach to a setting. A bit like saying that Howard Becker is a “cultural institution interviewer.”

There is a space here. But we have yet to populate it with theory that has been developed here. It is hard to be either heterodox or orthodox when all your doxa is elsewhere. We use theory, but we tend to borrow it from other domains, and too often, it is barely changed in the borrowing. Work in industry is often, at least implicitly, treated like a field site. Industry is a place where theory might be tried out, tested, but it is not what theory is about. For some reason, the very well known movie image of the hero of Mission Impossible, suspended above the floor of the top-secret vault, but touching nothing, came to mind. Dropped in from above, getting very close without ever putting a foot down.

Application of methodology to an arena doesn’t make a domain, or a discipline. Theory debate does. Theory must engage the conversations here, work in this set of gaps and spaces. And we need to articulate the characteristics of the space itself which peculiarly affect the development of theory. To play a central role, and to have continuity, theory can’t simply be a frame around the execution of research while remaining grounded in some other domain’s core questions, core lines of argument and central conceptual definitions.

The continual evolution of questions at the heart of theoretical dialogue cannot happen without language and a body of work against which to frame them. We may be looking at women’s deodorants for the fifteenth time, but does the fact that we are doing it for a client mean that we need to pretend that we are doing so for the first time? Topics like this will only get more interesting if there are constructs to be interrogated, if there is theory to be extended in and through the examination of them.

I recognize that there is not a particular definition or description of what “counts” as theory here. We bring differences even in that from our different disciplinary roots. Building a definition of what theory is and does for us must be a long arc of conversation and in some senses, it will be a yardstick of disciplinary maturity.

So perhaps it is not so much a question of locating “here” as it is of engaging with the place where we find ourselves already. Best said, I’d argue, in the immortal 70’s bumper-sticker phrase of Baba Ram Dass, “Be Here Now.”

WHO ELSE IS IN THIS CONVERSATION?

One of the opportunities slash challenges for theory in this space is that there are a lot of interested parties out there in the dark:

Practitioners: One of the great attractions of this space is that so many of the people working in it begin self-introductions with, “well, I used to do… but then I …” or, “I was trained as a …., but I’ve done a lot of work with …” Interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity is nearly an assumed condition of work in industry. In everyday practice we have conversations –whether explicitly theoretical or not– with one another and with the respective disciplines and theoretical traditions from which we have emerged. There is no single, dominant voice, which is a good thing, and there is the consequent opportunity to bridge and influence thinking with the work from a very wide range of disciplines—which is even a better thing.

Participants: The engagement with the various communities we study—whether conceived of as ‘users’ or ‘consumers’ or ‘patients’—is one I think we run the risk of taking for granted. The reality of working in this space is that many of the routines and questions for research and researchers, many of the expectations at work among our clients come not from humanist or interpretive disciplines in academia, but from the practices of marketing and market research. When someone is a “respondent” it is easy to end the dialogue as soon as you walk out the door, and to proceed under the fiction that we know them through their answers. If we are not cautious, we run the risk of substituting interrogation for conversation.

The other interested theorists: Recently, my colleague Hugh Dubberly—a student of both theory and of representations—introduced me to Stafford Beer’s Decision and Control: The meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics. Beer’s curiously dated work—“management cybernetics” should peg it pretty well for you—has a gem of a model in it that Hugh quite rightly thinks transcends the original context of Beer’s investigations.

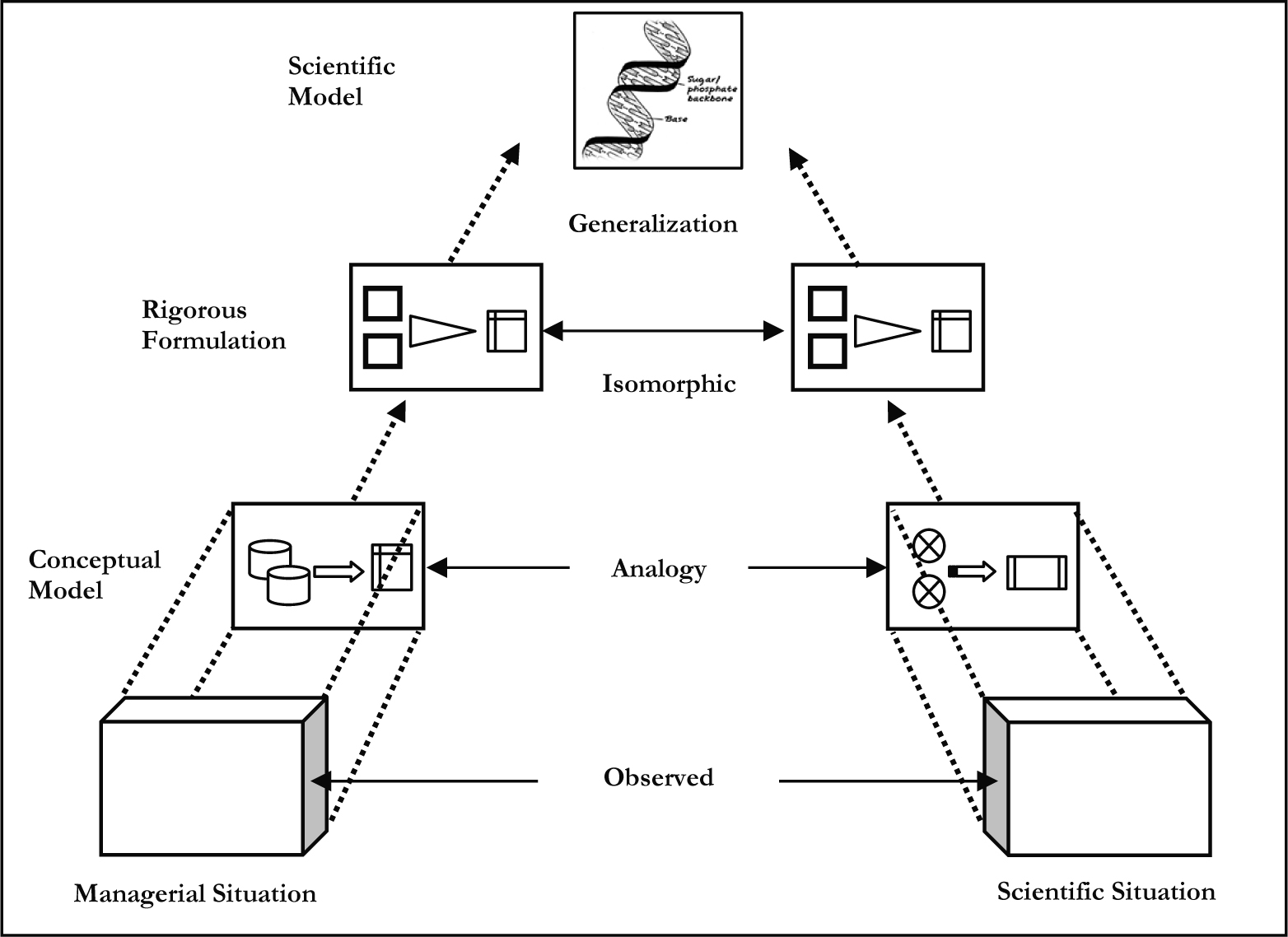

FIGURE 1 After Beer, Stafford: Decision and Control: The meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics.

Part of the work of theory is to move from cases to consensus, from particulars to generalizations. In the interpretive social sciences, this move isn’t a brick-by-brick testing of facts and observations, but rather a reconciliation and testing of explanatory frameworks and/or models against what we see in the world. Beer’s diagram does a remarkable job of bringing to our attention the fact that there is more than one model involved in that process. In applied work, in other words, we don’t just reconcile our conceptualizations to the ‘facts’ or the observations we’ve made, but we must reconcile the models that we build or employ with the models of the people or institutions on whose behalf we are doing this investigation.

It may be forty years old, but I think that a couple of the implications in this representation are very fresh. On the one hand, instead of “management science” he could just as easily have been talking about the idea of reconciling a medical model with a patient model, a user model with a software engineer’s model, or any of the other kinds of things we study on a regular basis. That in itself is a nice adjustment.

On the other hand is the notion that the second model of “the situation” belonged not to the managers on the floor of the factory (the ‘subjects’ of the studies) but to the management science and management theorists whose theoretical models of production and technology had guided the original design of the systems he studied. What Beer is pointing out here is that the same move we need to make to get from idiosyncratic cases to defensible explanatory reach is deeply tied to the move we make to insure that the model will be useful and effective for what is, for all intents and purposes in our world, “the client”. The relationship isn’t just between researcher and subject, but between researcher, subject and client, each of whom brings a formulation of the situation to any of the interactions we study.

Clients and clients’ frameworks. There is that other listener lurking in the dark. And one that many researchers seem to talk to only reluctantly. We study consumers or users or experts or sufferers without hesitation. That relationship is central, comfortable, and expected. But in this space the value of the work will always be in part determined by the degree to and the success with which it engages the end users of the research, the clients – whether they be designers, engineers, brand managers or policy makers. This process of matching the model we make of the situation with theirs, of engaging them in conversation so that what emerges from the process Beer calls “rigorous formulation” is useful as well as accurate is, I think, one of the defining characteristics of this domain with which theory (here) must engage.

To do theory in and of the space, you must accurately and realistically recognize the actors. In industry, that includes clients. In this space, clients are not foundations or public granting agencies; there are strings attached—our work must be effective in a very real sense of the word. If we approach our work in industry having made explicit the idea of engagement, of moving through analysis to this sort of reconciled formulation of models, it would seem to provide a more sustainable way of ‘being here now’ than an uncomfortable and distant accommodation with the vaguely threatening notion of ‘serving corporate interests.’ This means that we need to develop a deep understanding of what different client constituencies do with studies, to understand what constitutes effectiveness in the organizations we work with. They are as deeply part of our conversation as any of the people or places or interactions we study on their behalf.

WHY THEORY MATTERS, ESPECIALLY HERE

In the process that Beer’s model suggests, there is one other element that I like a great deal, and which brings me to my last bit of metaphor flogging. That is the idea that through the processes of analogizing and reformulation and testing, all the models change. Given that we are talking about pretty fundamental models here – basic conceptions of how things work, about what is involved or what matters in arenas of experience—the idea that we are looking to change how our interlocutors think is loaded with both opportunity and responsibility.

There is a final, simple framework I’d like to use to extend that point a bit further.

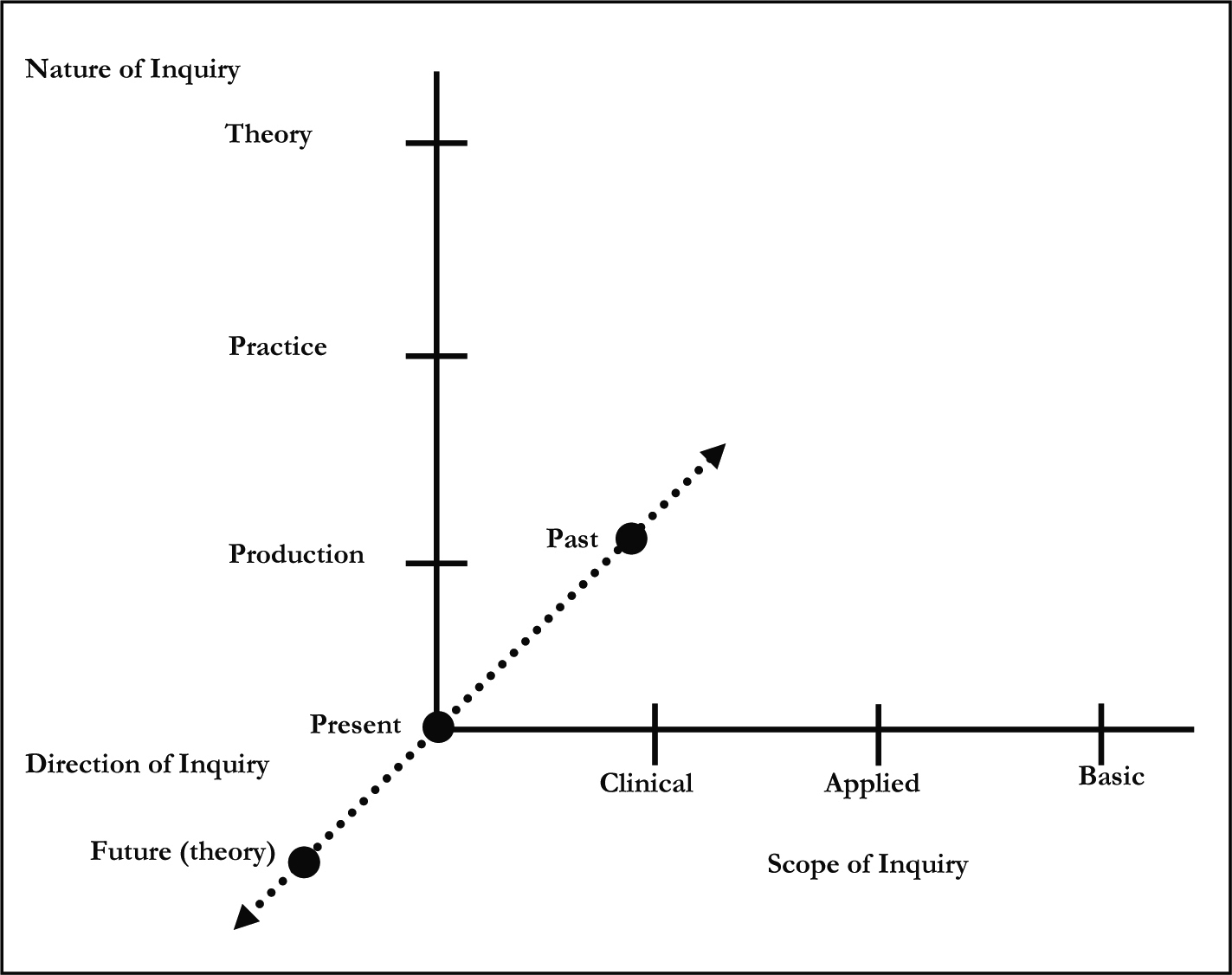

FIGURE 2. After Buchanan, Richard: Design As Inquiry: The Common, Future and Current Ground of Design.

This is the most recent iteration of a way of talking about design research that Dick Buchanan (until recently the chair of one of the best design departments in the country, and who “used to do” Rhetoric in the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought) has been working on for quite a while. Buchanan’s diagram means to sketch out a conceptual space, and to indicate that in each of its intersections, the nature and requirements of design research are different. Pulling the diagram out of the paper is massively unfair to the argument, making a careful articulation seem much too simplistic. But the points I need it to make this morning are in fact, rather simple ones.

The vertical axis is a pretty clear one, asking what drives a particular inquiry – from the immediate needs of production, through questions of (design) practice out to questions generated by theory. Were we to lay out all the papers about “ethnography in industry” along this axis, the result wouldn’t be very top-heavy. That, at least, is one of the things I think we all know, and one of the explicit reasons for this session, this conference.

The horizontal or “scope of inquiry” dimension presses a slightly different question upon us. By “clinical” Buchanan refers to work primarily based on case studies. Again, were we to plot relevant work in the field, “skew” would be a barely adequate description of the result. A single case study is often a powerful thing. But theory cannot be built on cases alone, especially when one case is rarely connected to the next. It is, as Buchanan’s diagram implies, a limited ‘scope of inquiry’. If case studies are the only fodder for the conversation, there is no extension, little reach beyond the immediate, and no larger patterns or emergent issues for theory to make sense of. This is almost certainly related to a lack of citation and acknowledgement of one another’s work. Without that, there is no central corpus upon which to build meta analyses.

But I think the single most important thing to draw from this model is found on his z axis: past, present, and future as the ‘direction’ of inquiry. Future has this little parenthesis after it: “(theory)”. What does that mean? Obviously, it could be prediction, in the sense of extending our understanding of the current situation into likely sequelae in the future. But there is also a much more potent way to understand it: that in this space—the “here” we are trying to articulate at this conference—theory of the future also develops the future, conditions the future.

In the gap between what is (now) and what might be, articulating and developing theory is action. This is especially true of the representations of theory we develop and deploy. Because we are in this conversation with the people and organizations who will populate the future with artifacts, affordances, tools, and ways of thinking, we are actively engaged in shaping the future. We are not simply observers, describers, or contemplators of it.

Where there is active engagement, there is both power and responsibility. When was the last time someone asked any of our practices to develop a research project that would do no more than summarize the history of a particular product’s use? Or to describe the current composition and behavior of a particular group without the implicit agenda of somehow changing it? We act at this intersection, and we act in a way that inflects the directions of the companies and institutions who make the everyday world, who shape power and politics, whose values are literally ‘materialized’ in a thousand ways each day. We cannot ignore the fact that we have both considerable influence on the future nor the consequent responsibility for using it.

If we only think of theory as what we learned in graduate school before we started to do the work we do here, we do not grasp an important opportunity. When we work in this space atheoretically, or when we think that “real theory” happens in the academic mother ships of our disciplines, we abdicate both the power and the responsibility inherent in it. We shouldn’t.

As I’ve thought about this talk and this topic over the past few months, a line from one of the formative texts of my youth kept popping back into my head.

Something about the blend of conversational directness, an edge of anger, and an optimistic commitment to action makes it a perfectly epigrammatic conclusion: “I don’t fuck much with the past, but I fuck plenty with the future.” (Patti Smith, Easter/Babelogue, 1978).

So, welcome to the theory section of EPIC. Jeanette Blomberg is responsible for the ‘P’ in EPIC being “praxis” rather than ‘practice,’ and I think we all owe her a debt of gratitude for insisting on that small change. Practice is a good thing, in all the connotations and implications of the term. But the simplest translation of praxis is “meaningful action” and that’s what the conversations we start here today can be.

We were blessed with a wealth of excellent submissions in this area, and the decision to limit the number of talks so that we could give each paper the time to push thought and argument beyond the usual 15 or 20 minute slot was a difficult one, but the we thought it was the right commitment to make. After seeing them, we hope you’ll agree.

Acknowledgments. Thanks to Kris Cohen for his usual blend of appreciation with precise critical perception of an argument’s weak spots and omissions. Thanks to Hugh Dubberly and Ari Shapiro for (very enjoyable) conversations and discussions which contributed substantially to my thinking on this topic.

Rick E. Robinson is Global Director for GfK NOP’s Observational and Ethnographic practice. Rick holds a Ph.D. in Human Development from the University of Chicago. He has been a leader in developing and applying observational research as a basis for new product, service and strategy solutions. He was a co-founder of E-Lab, a research consultancy, which pioneered new research approaches for understanding the interactions between people and products. In 1999, E-Lab was acquired by Sapient, where Rick became Chief Experience Officer and developed the Experience Modeling (XMod) practice. Among his clients have been BP/Amoco, BMW, Ford, General Mills, General Motors, Hallmark, Intel, McDonald’s, Nabisco, Novartis, Pfizer, Samsung, Sony, and Unilever. He is the co-author of The Art of Seeing with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He is currently working on a book on the principles of ethnographic practice for design and product development.

Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2005,pp. 1–8. © American Anthropological Association, some rights reserved.

REFERENCES CITED

Beer, Stafford

1966 Decision and Control: The meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics. New York: John Wiley.

Buchanan, Richard

2005 Design As Inquiry: The Common, Future and Current Ground of Design. Presidential Address to Design Research Society, Annual Meeting 2005.