A local division of a multinational manufacturer was experiencing declining enagagement and perceptions of leadership (measured in employee satisfaction surveys). In anticipation of coming waves of organizational change, they asked the research team to explore how “nostalgia” may be contributing to these issues and how they might define the unique culture of the division.

Combining ethnographic observations with other qualitative methods, across all levels and departments of the plant, the team uncovered other, more critical issues. Having built a trusting relationship with senior management of the plant, the team used extensive work sessions to help them to understand issues from employee perspectives. This new empathy was conveyed during validation session that spurred initiatives to address a variety of isssues that had been contributing to the problems that initially spurred the project.

AN INITIAL REQUEST THAT LEFT RESEARCHERS THIRSTY FOR MORE

The president and the VP of human resources of a global organization faced challenges at the local plant, notably with productivity and gradual but constant declines in engagement and leadership levels over the past 4 years, as measured by bi-annual employee satisfaction surveys. Increasing pressure for performance was identified as one factor, but management also felt that nostalgia was an issue, and brought the focus to specific cultural characteristics of the organization that needed to be better understood and shaped.

The VP of human resources had experience with ethnography while working in Europe and understood its ability to provide a better understanding of identity, culture and their relationship to the product being manufactured. She felt that understanding local history and culture at this plant, located in Quebec, was important, particularly given that this unit was also under scrutiny by the North American regional group to which it belonged regarding its performance. To be considered representative by the various stakeholders, the project would need to be of fairly wide scope, taking into account a broad range of perspectives from constituencies, including 13 departments, 4 shifts, differences in seniority, union representation, and managerial perspectives at various levels.

The research team was excited to receive a request from a potential client already familiar with an ethnographic approach, but nonetheless felt a need to clarify research expectations and fully understand how the results would be used. As O’Connor and Dornfeld (2014) illustrates so well, “when we listen to people talk about the problems they are having with “culture”, we know what they really mean: Our organization is stuck. We’re not quite sure how or why. Or what to do about it.”. During this initial project definition period, the researchers were already taking note of a variety of factors, including interpersonal behavior, communications, spatial organization and the omnipresence of corporate messaging about promoted values. These revealed a tension between the insistence on humanistic values, the constant reference to ambitious goals, the apparent clear separation between plant employees and head office employees sharing the same building, and the lack of investment in a common space, such as a cafeteria. The research team wondered whether the company management was too committed to a top down management style to embrace the adoption of new perspectives. Intellectually, these questions transported the team back to their university years, when they bathed in concepts associated with the dynamics of power, class fractions and symbolic forms of violence as developed by Gramsci, Bourdieu and Foucault. They were witnessing expressions of a structural power but also the expression of its more diffused forms as embodied in discourse.

Another concern was that management aimed at pinpointing specific elements of Quebec culture as responsible for performance challenges. In discussions of the client’s current hypotheses, there was a recurrent statement that it generally took more time to implement changes at the Quebec plant compared to everywhere else in the regional group, and that this was due to cultural traits where both consensus and resistance to change were valued. This pointing to culture could potentially translate into a mechanical and reductive vision aiming at a change without a real effort to consider the role of interactions. Agreeing with Ron Leeman’s advice (2016) about organizational culture changes, the research team recommended caution when it came to the temptation to use the local context and culture to explain organizational challenges. Citing Leeman, the team explained, ‘Culture’ is merely a notion. Cultures can’t interact… People interact!”, and that it was important to start from an exploration of interactions. The members of the client team had varied and polarized views and opinions on the influence of the Quebec culture on productivity, but everyone agreed to start from interactions.

There were many meetings before everyone agreed on a final research design. In between, the research team, exploring the literature on topical issues mentioned by the client, proposed new angles from which to explore the situation on the ground. At the same time, both the client and the research team each had concerns and stakes that needed to be mutually understood as part of building a relationship of confidence and trust.

This process enabled the refining of the main objectives and the definition of enough elements, including the deliverables, for everyone to believe they were understood (Table 1).

Table 1. Respective concerns and stakes

| Management Team | Research Team |

|---|---|

|

|

Collectively we built a level of trust that made us all sufficiently comfortable working with so many remaining levels of uncertainty.

By the end of this negotiation, the VP of human resources responsible for commissioning the study had spawned a broader, company-wide initiative aimed at developing a common mission statement that could be shared by everyone in a context of continuous and ambitious growth objectives.

Having commissioned the making of documentary videos exploring the company’s history, the sponsor narrowed the research team’s focus to gaining a clear understanding of ‘who we are and how we behave.’ Methodologically, the team put ethnographic observation at the core, supplemented by in-depth interviews and focus groups, while drawing upon a variety of analytical tools and concepts both from the social and business sciences or literature.

APPROACH

The research was conducted with 50 plant employees across all departments, all levels of the corporate hierarchy and all shifts, both unionized and non-unionized. An ethnographic approach including multiple methods was employed across five months of fieldwork, combined with intensive work sessions with top management and follow-up validation/brainstorming sessions bringing together all participants and management.

Although the team initially anticipated shadowing employees throughout their entire shift, plant management felt that 3-hour increments with multiple employees would be more fruitful. This was indeed the case, and it allowed the team to get an up-close look at the work environments, demands and challenges faced at more positions and across more departments. At the same time, it gave the researchers more visibility within the plant, which helped to encourage increased research participation.

The research team insisted that a validation phase be included in the research, wherein they would circle back with participants to ensure that the team’s interpretations did in fact capture their perspectives. It was not stipulated up front what form this validation process would take, but was left to be negotiated with upper management in the plant.

FIELDWORK INITIATION

Fieldwork began following the presentation of the research team at a large quarterly assembly. Initially the team was given factory tours and interviewed all levels of management along with some of the factory-floor employees. It should be noted that participation was voluntary, but was scheduled during normal shift hours. This necessitated significant coordination efforts by the human resources as the company’s production lines operated with only a limited contingent of substitute workers.

During the initial weeks of fieldwork, the researchers identified a number of competing orientations and frames of reference that were contributing to the central issues. Nonetheless, this early data was proving to be so complex and multifaceted that the researchers felt unsure about defining the issues to tackle. They regularly presented fieldwork reports and preliminary findings to the management team to obtain their reactions and feedback, which allowed them to make decisions on aspects to further document. Initial findings were all about pressure, miscommunications and misunderstandings of respective aspirations.

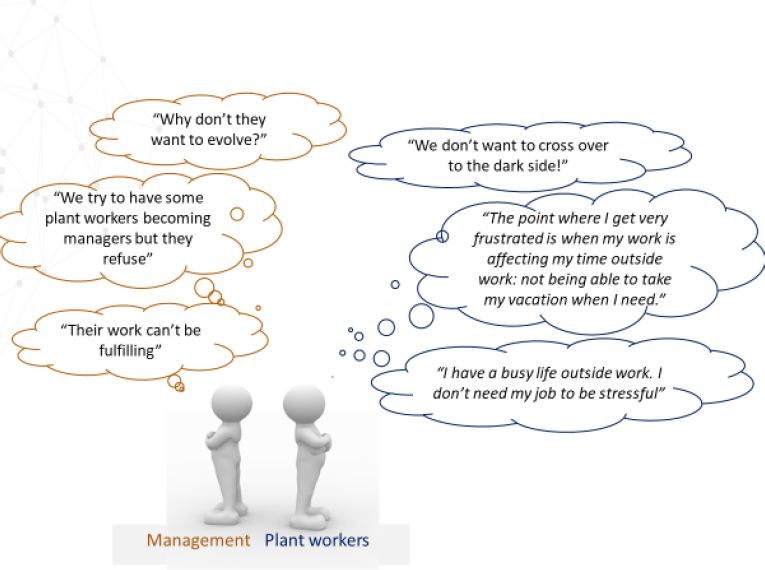

Figure 1. Different views on the place of work in life.

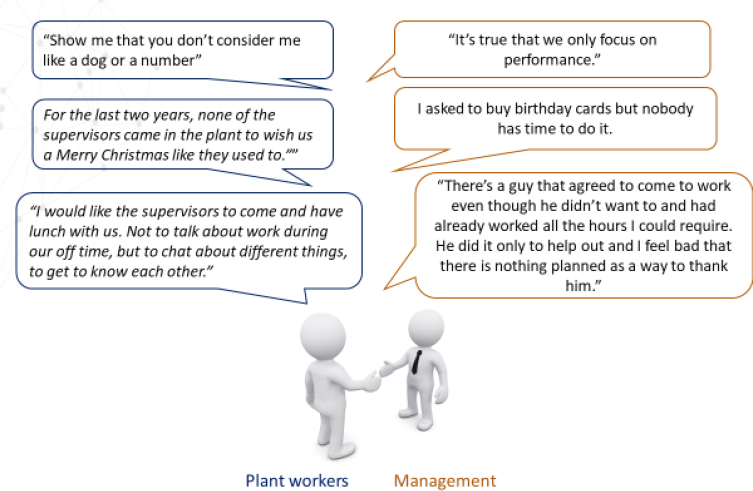

The plant leadership was trying to evolve a more responsible and autonomous workforce, but was relying on a “command and control” leadership style to push through change and motivate the workers. While management was studying innovative approaches to reward employees based on performance, plant workers were asking for something else–they wanted to feel acknowledged and appreciated as individuals by their managers. They wanted personal interactions and a reduction of the distance between managers and workers. In other words, they were looking for existential recognition as a basis for meaningfulness at work.

As fieldwork progressed, discussions between management and the research team revealed that several competing orientations and frames of reference were contributing to the central issues. The researchers found a rich culture of collaboration and a pride in the company’s products that was being eroded due to a perceived imbalance between increased pressure and a sense that the valuing of human inter-relations in the work environment was deteriorating. Multiple psychodynamic factors were also contributing to a negative discourse.

Figure 2. Lack of recognition and acknowledgement.

A number of gaps were observed between how people in management positions and plant employees evaluated work and its place in their lives. This generated misunderstandings, sometimes leading to judgmental opinions and frustration. It is important to note that the salary gap between plant workers and many of the managers was not significant and that some of the plant workers putting in overtime hours would earn more than some of their managers.

The erosion of engagement and the willingness to be attentive to each other was not only occurring among unionized workers, but also among managers who felt trapped between the increasing demands from top management and the employees. This notably translated into an attitude whereby managers usually tried to comply with any requests from their superiors even when they disagreed.

Independently of all these tensions, one of the most striking initial findings was the strong identification with the company, its products and its ongoing success, that was shared at all levels of the company.

Bringing Attention to Difficult Business Questions

Moving from interviews to factory observations proved particularly revealing, enabling the research team to better understand the contexts to which employees and managers referred during interviews. It provided the researchers with a concrete understanding of the collaborative culture within the plant, as well as differences in ambiance between shifts. It also helped the team identify and request additional observations at key times, such as work cell meetings and shift changes. These observations were crucial to identifying some of the more difficult business issues and the contributing dynamics.

“Forced” Overtime

Finding workers who agreed to do overtime was sometimes a challenge that management had tried to address in the past without much success. Management felt that the current union contract limited the options for a rotation that would include a mix of unionized full time and temporary workers. This resulted in having to pressure temporary workers to come to work for supplemental shifts.

This pressure and the regular effort needed to find employees who would agree to come to work when there was extended production, resulted in everyone talking about “forced overtime”. The pressure exerted on some of the temporary workers, the methods used and the impact this had on the personal life of these workers was a dominant theme in all interviews, with older unionized employees who were not affected by overtime requests feeling that this was unfair as well. Management, workers, and union leaders felt there wasn’t much that could be done in a context where workforce needs could be highly variable.

The person responsible for scheduling overtime developed various strategies to apply pressure on temporary workers. When being interviewed, he indicated often feeling trapped and not being sure about what to do next. He also felt he didn’t have a means of showing gratitude to workers who would try to help, particularly in situations when they could have refused the added work. For example, he wished he could offer them a free meal during the overtime.

The research team’s interventions first aimed at communicating that this problem required attention. A few points in the ongoing discussions contributed to a change in perspective. One of them was to question the methods used, the second aspect was to tell stories about some of the impacts of the current strategies: “The way my kids appreciate me as a father changed since I work here. I’m not there for them and I repeatedly announce at the last minute that I’m cancelling or not attending family activities.” Although, the team later learned that the negative impacts were affecting only a small number of employees, a substantial proportion of the other employees felt this was unfair.

Assimilating this information, management went from thinking the pressure being used was legitimate, to realizing it was a problem. A dialogue between upper management and the research team regarding what had been tried before and what else could be envisioned in the future ensued. This highlighted some key information gaps. The management team didn’t know how many workers faced pressure to come to work when they would have preferred not to. They were not documenting when shortages of employees willing to perform overtime occur and how frequently this happens. They were unaware of the processes used and didn’t realize that some temporary workers were able to negotiate a planned overtime or no overtime, while others felt there was no room for discussion. All of this new information led to the identification of innovative ways of potentially managing overtime scheduling, as well as the implementation of a tracking system to avoid excessive reliance on the same employees.

Perceived Lack of Ambition: Us and Them

One of the project sponsor’s initial areas of interest was how to motivate plant workers. During the interviews with managers, this was described as a challenge due to the resistance to change they were facing. The managers felt that employees did not have an ambition to grow in the company, and provided examples of employees who opted to change position for a less remunerated job or one that management deemed less interesting.

Plant workers, for their part, indicated almost the opposite. They were proud of working for the company and aspired to contribute to its progress and success. However, they did not feel that they were listened to or valued. Some of the plant workers felt that many of the young engineers who were supervisors have neither the experience, knowledge nor interest in getting a deeper understanding of plant laborers’ work, or of the workers themselves, as people. Plant workers were asking for time, often in less formal settings than meetings, to share views with other workers and managers.

Managers did not realize how some shortcomings in their own behaviors and processes where negatively impacting worker morale and performance. They also didn’t recognize some of the efforts and initiatives that employees were independently making to ensure productivity. For example,

- There was insufficient recognition of talent and worker contribution beyond apparent performance, which also led to questions about how performance was assessed.

- Communication of information pertinent to production runs was spotty, and the use of a new electronic communication tool had not been optimized, leading to important information gaps.

- Work organization and prioritisation included both formal and informal aspects, the latter of which was often organized between workers from different shifts.

- Relationships and communication were crucial in a context where trouble shooting is a continuous dimension of work and productivity. On-the-ground knowledge of specific machines and of the many potential issues that may cause a production line to stop was key in accurate trouble shooting.

It took time and plenty of storytelling for management to start understanding that plant workers, particularly operators, didn’t “feel” or “see” work the same way they did.

It also took time and open-hearted conversations for the research team to understand that although plant workers didn’t share the same hierarchal status as managers, they had advantages that were not shared by their managers, and that this situation also contributed to misunderstandings:

- They were protected by a union.

- Due to overtime, they were often earning as much money as managers for similar hours.

- They had a shift organization that facilitated an investment in family life, other projects, education or overtime.

- They often had stability.

- They had the freedom to stop thinking about work when their shift finished.

Managers, who felt trapped between the increasing demands from the top management and employees, sometimes acted as if they needed to release tension. This situation explained various dimensions that were identified as exacerbating mutual incomprehension and frustrations, and that were ultimately leading to slippages in human relations, such as:

- Inappropriate and humiliating language used by some of the managers when referring to plant workers

- An improvised evaluation process

- A systematic one-way communication pattern

As fieldwork continued to reveal unanticipated contributing factors and issues, repeated and regular exchanges with the plant’s top management became key in supporting a process of recalibrating hypothesis and assumptions, and in helping them fully take in the competing frames of reference that were presented. Following analysis, multiple extended work sessions helped management digest the more difficult insights and develop strategies that the workforce was likely to embrace.

RESULTS

From the outset, this project did not include a final workshop or coaching component and was limited to exposing existing issues and proposing potential avenues for improving them. Nonetheless, the extended time frame between project conception and the completion of fieldwork allowed for a certain amount of de facto coaching, particularly with the factory’s upper management. The numerous meetings with both the head of human resources and the Vice President of the plant enabled the research team to progressively share their developing findings, along with some thought starters regarding potential solutions. The researchers typically provided them with articles from management journals that helped to define and break down the concepts, along with potential ways of addressing the issues they were bringing forward. This approach and the frequent touch points gradually encouraged management to re-frame how they saw situations so as to better understand employees’ perspectives on emotionally charged issues.

A good case in point occurred at a meeting relatively early in the fieldwork process. The researchers highlighted the fact that employees were feeling under-appreciated and were therefore in need of some form of recognition from management. Employees were not necessarily looking to be called out in front of their peers for outstanding performance, something that felt at odds with their collaborative spirit. What was emerging was a desire for existential recognition–an acknowledgement and appreciation of them as people. To support this discussion, the team provided an article on employee recognition by J.P. Brun (2008) , a thought starter infographic on the gamification of performance management (Messaoud 2015), and a promise to further refine their understanding of what would be meaningful to employees during the remainder of the fieldwork.

This helped to kick-start some preliminary initiatives undertaken by management, notably the formation of a recognition committee composed of both workers and managers. This began while fieldwork was still being conducted and was reflected in subsequent interviews and focus groups with employees who cited this committee as an indicator that things were starting to improve.

Interestingly, the extended presence of the researchers in the factory over several months was also a contributor to the change in attitude that they found between early reactions to their project and later ones. The first participants, as well as employees who refused to participate, made it clear that this project was a nice initiative, but that nothing would come of it, as was the case with past initiatives. The researchers acknowledged employees’ skepticism and emphasized that this project had support from the highest levels of the company, and that they were fairly certain that the results would be taken seriously. Moreover, they assured participants that they would convey the collective points of view that were being shared. Such assurances were supported by management’s continued reference to the “Sapiens” project, as the research came to be called.

Developing Empathy

As the team moved from fieldwork into analysis and ultimately the presentation of the research findings, it became more and more clear that for this project to be a success, it would be important for management to deeply embrace the findings. This did not mean that the client had to agree with the employees’ points of view conveyed by the research team, but they would need to suspend their own perspective to get into the mind space of their employees if they were to create a truly open dialogue with employees that would make them feel heard. Management needed to try to understand how their employees felt.

It quickly became apparent that this would be a process requiring multiple work sessions with top management of the factory. The initial presentation of the findings was met with some resistance, particularly when management indicated that what employees were saying was factually incorrect. The research team emphasized that even if employees were mistaken about events, this was their interpretation. For management to have a constructive dialogue with their employees, they would need to accept that this, along with all the associated emotions, was the perspective of the employees. Furthermore, some of the findings were presented in a way intended to shock, precisely because behavior across all levels of management had undergone slippage, with disrespectful comments and interactions becoming commonplace. A second work session made significant headway as management had had time to re-read and digest the content of the report, making them more open to trying to empathize with the stories the researchers were sharing. The client was intellectually assimilating the employees’ perspectives that the team was conveying.

Matrix Creation

Following the initial work sessions, the client requested that the researchers condense the findings into a matrix including major themes, sub-themes, potential actions to be taken, why this mattered (the findings) and a brief example or quote. Although this exercise felt like it was inverting the storytelling while alienating key issues from the situational contexts in which they are embedded, it also forced the researchers to transform findings into action statements and to look at the complexity of their findings from additional angles. More specifically, it forced them to frame the findings in a way that readily fit with their client’s decision-making process and facilitated thinking about potential solutions and the feasibility of their implementation.

Figure 3. Matrix of findings

This matrix, covering 4 main themes and 14 sub-themes, became the basis for a third work session wherein the researchers and top management evaluated the relative importance of each issue and the feasibility of executing on them in a relatively short timeframe. The decisions coming out of this session were used to select the key findings which would be potentially actionable and would be presented to employees during the validation sessions.

Validation Sessions

From the project’s outset, the research team insisted that there be a validation mechanism whereby the researchers could verify with workers whether they had accurately captured the issues that had been shared. As client and researchers had left the exact format of this validation to be determined, management ultimately decided to present the research findings themselves, with the researchers present, as part of open dialogue sessions. Management felt it prudent to select sub-themes for which they could propose near-term potential solutions as a way of offering thought starters for discussion. While the researchers were initially skeptical about this approach, the presence of a research team member at each of the validation sessions enabled them to offer clarification where needed, while also providing reassurance to the employees that management was accurately presenting the research findings. Management was able to communicate a real openness and willingness to listen, and the employees took them up on it, often recounting some of the same comments and stories that the research team had already shared with management. This forum proved invaluable in helping management take a final step in empathizing with how their employees felt, not just intellectually, but emotionally. Participants not only validated the findings, but also insisted on telling more, which proved to be very compelling. The research team was amazed to witness how much surprise and excitement was expressed by the management team as they reached a new level of revelation and a fuller realization of the opportunities. Management also asked what would be needed to avoid having to hire an outside team to help management and employees better communicate when there is tension in the future, with employees responding that there should be more open discussions like these. By the end of the sessions, multiple employees insisted on thanking the researchers for helping them be heard. The validation sessions were also a rewarding moment for the research team who felt like they were witnessing the first impacts of the research unfold before their eyes.

The plant’s upper management presented a fuller version of the findings to all the mid- and lower level managers, which included direct critiques of some of the behaviors the research team had observed among them. The researchers were told that the audience readily accepted the findings, with individual managers admitting that they could see themselves in some of what was reported and that they clearly had areas to improve.

Post-Project Changes

Although the research team were not involved with the implementation of solutions beyond the validation phase, subsequent conversations with the client revealed a considerable number of changes that were put in place as a result of the research.

Prior to the research, the company had embarked on an effort to put in place a structure allowing for proximity management. But while this structure existed, ongoing behaviors and processes were not allowing it to achieve its desired effect–to provide accessible support as employees were progressively encouraged to be more responsible, self-directed and accountable. This has apparently changed because of this research. Each work cell manager was given the mandate to develop their own plan for improving communication flows, understanding, empathy and coaching, in consultation with their employee team. Taking to heart the theme of advocating on behalf of your team, one manager even requested a delay in complying with a human resource request because doing so immediately would “disrupt my Sapiens.” This has become the de facto term of reference for managers’ new mindset and approach to creating an environment of collaboration, trust and empathetic understanding.

The manager of the shipping and receiving department extended this new-found empathy to relations between his team and the team at their just-in-time logistics partner. The teams of the two companies went on cross-site visits to show each other some of the issues they face, particularly because of the way the other team performed their job. This has led to a greater understanding between the two teams, such that they now avoid practices known to make the job harder for their alter-ego at the other company. For them, developing empathy helped to increase efficiency.

Recognizing that they had to address the occasional need to compel employee overtime work, management has instituted a system wherein they provide a four-week advance view of anticipated scheduling. Management emphasized that the schedule was not a guarantee, and that hours may change depending on actual demand. Having this advance notice, even if subject to change, has allowed employees to better plan their lives. The renewed attention to employee’s well-being also had an impact on a new effort to arrange a fast-track reporting system with unemployment during a temporary layoff. This enabled employees to easily file a claim and receive benefits during weeks when some or all of their hours were cut. According to management, employees have commented that this demonstrates that management cares about their employees.

Finally, management has implemented measures to address the recognition deficit. Employees now receive birthday cards with personalized messages from the Vice President of the Plant. Although this might be considered a token gesture, it has had a significant impact on morale, particularly when coworkers see that a colleague has received a card and pass the word around that it is their coworkers’ birthday. Even employees who were described as among the most negative have gone out of their way to make positive comments about this practice.

Although the research team has not been able to assess firsthand the actions implemented and has not heard employees’ perspectives on what has changed, it would seem that when organizations embrace empathy, even very simple solutions are able to defuse emotionally charged issues.

DISCUSSION

When initially planning, negotiating the scope and setting expectations of a research project within a complex organization several factors should be taken into consideration, as they can impact the quality of the findings and their perceived credibility.

It is important to aim at best-informed consent from participants, including the management team, in order to build trust among participants. This includes protecting confidentiality even if it means not fully providing insights or not supplying enough information to support their credibility. At the same time, the research team should maintain a clear and transparent position on their role, who is commissioning the research and why.

Extended field time, although not necessarily ideal for the research team’s time management, can itself be a factor in creating conditions for success. This necessitates flexibility on the part of the research team which may need to adjust their anticipated approach for the ethnographic observations.

Researchers should be prepared to navigate between powerful adversarial stakeholders (e.g. management, union reps). Gaining an understanding of these perspectives can shed light on broader workplace dynamics and may help to clarify issues raised by other stakeholders.

You don’t know what you don’t know during the project design phase and at the outset of research. Researchers rely on the client to inform them about the relevant parameters to take into consideration (e.g. the number of departments, the company’s organizational structure). If the project sponsor in not sufficiently familiar with some of the pertinent on-the-ground parameters that could affect the research, request an early meeting with a key informant who can provide you with this information as it may alter the research design.

Context and Success Factors

By the end of the research, anthropologists may have an appreciation of the complexity of the situation and what they have uncovered and may believe that storytelling is the best way to convey findings. Clients, however, want a much more simplified and structured problem-solution approach that radically distills complex findings. As cultural translators, researchers must also learn to speak the client’s language, while not losing the empathy-building quality conveyed through storytelling. The research team believes that the multi-meeting process by which the client team assimilated the findings was essential to the building of empathy and that providing the matrix of insights and recommended actions earlier in the process would have short-circuited this valuable process.

Client organizations exist in an environment that is impacted by their relationships–contractual, structural or otherwise–that limit their choices. In this case, the organization was part of a multinational. As such, local management was sometimes forced to implement policies and changes that went against the prevailing ethos at their site. The research team must also take these constraints into account. Similarly, union contracts can constrain the latitude that management has to alter labor practices such as the allocation of overtime work. Researchers may need to familiarize themselves with these contracts to identify windows for reconciling inconsistent on-the-ground practices that nonetheless conform with contract stipulations.

This project was able to achieve positive outcomes despite the fact that the consulting researchers did not have an extended coaching role and were not involved in developing a change plan for the client. The researchers believe that this was due in large part to the strength and positive orientations of the underlying company culture, despite their current problems. The company’s highly collaborative spirit and the generally congenial workplace were able to support the corrective actions due to an overarching goodwill towards the company and a fondness for what the workplace environment had traditionally been like.

The management team’s significant personal investment in the project was a major factor in the success of the approach; they maintained the ownership of the project from beginning to end. They believed in the approach and supported the research team. They accepted to be challenged, and were very attentive to what was communicated. They adopted new perspectives and maintained a transparent and humble attitude when discussing results and changes with their employees.

Perspectives on Organizational Research

While the research for this project was being conducted, management at the plant faced repeated questioning and criticism from their regional superiors about the decision to hire outside consultants, and specifically ethnographers to understand what was the cause of declining engagement and perceptions of leadership. Given this context, the research team felt added pressure to not only provide insights and actionable recommendations, but to demonstrate the value-added that their training and positioning brought to the inquiry. The following factors were all determinant in making the project a success:

Ethnographers Take a Specific “Stance” – As they engage in fieldwork, they aim at suspending judgment in order to better understand and empathize with their research subjects. Although the researchers may have their own concerns and value judgments, including ethical concerns about how the findings may ultimately be used, these must not be allowed to cloud their ability to see alternate perspectives. At the same time, not being members or stakeholders of the organization, ethnographers are able to observe situations and interactions with a fresh, external perspective. This allows them to notice things that organization members, well versed in the unwritten rules of behavior and acceptability, take for granted. They compare not only differences between various stakeholders’ views and perspectives, but also discrepancies between what is being said and what is being done. Moreover, they are prepared to observe and look not only for what is happening, but what else could have been expected. But a key success factor also includes serving as ‘translators of perspectives’, gently guiding and supporting the client’s opening to other stakeholders’ perspectives.

Anthropologists Are More Than Ethnographers – Anthropologists provide more than just a journalistic report of what has been observed. They organize findings into insights and conduct literature reviews to identify theoretical models that other researchers have used to explain similar issues, both from social science and business journals. This recourse to theoretical thinking tools can broaden the researchers’ own perspective on their emerging findings and help feed into their own theory building. When suitable business journal articles are found, offering them to clients as interesting references can help to underscore the importance of their own research findings.

Social Scientists Are Trained to Work with Complexity – Social sciences, and particularly cultural anthropology, are based on a practice that requires specific skills but also an approach to support validity. It involves a continual back and forth process between fieldwork and analysis allowing for theory building and testing. This not only helps in managing complex streams of information, but also demands that the researchers confront their own assumptions and biases, both explicit and tacit. But researchers’ comfort in working with the complex web of factors that impact human interactions and interpretations must also yield to clients’ demands for more distilled outputs.

The hard sciences are focused on data with properties (hard, objective facts like weight and distance), while the human sciences collect data that allows us to see aspects, or the ways people experience such properties. (Madsbjerg et al. 2014)

Consultants Help Translate Insights into Opportunities – Beyond conducting research to uncover the underlying issues and the sources of both negative and positive dynamics in the workplace, the team also served as consultants, collaborating with the client to help them fully grasp the findings, insights and opportunity areas. Being able to provide actionable recommendations, or at least to structure insights in a way that facilitates brainstorming with the client, improves both their relevance and credibility.

Crucial Holistic Involvement – As Blache and Hofman (2007) elaborated, it is important to adopt a holistic approach that includes frequent interactions between client and research teams, as well as a client who is empowered to make iterative changes in the project’s direction and has the latitude and openness to explore alternative possibilities. This is essential as ethnographic work often uncovers significant unexpected findings that can at times be challenging to the client’s accepted wisdom. For this reason, it is advisable to have the client team participate in the research discovery process to ensure full assimilation and transmission of insights. In an organizational research context, however, direct client observation is not possible when addressing questions that involve inter-hierarchical tensions within the organization. In the absence of this kind of involvement, it is essential for there to be frequent touch points with the client to both verify the course of the research and to encourage their receptivity to alternative ways of viewing the issues that arise.

Cultivating Empathy – Ultimately, one of the most important outcomes of this project was the cultivation of empathy, particularly among management. It is only in the period following the completion of the project that the team realized the critical role that the process of helping clients to develop empathy with stakeholders that may view situations from a very different perspective than their own. Throughout the process management displayed attitudes of openness, but also rejection, a return to openness, and intellectual understanding. This culminated in validation sessions where upper management was ultimately able to emotionally embrace and empathize with the perspectives of both floor employees and lower levels of management. But following the project, the client’s ability to use empathy not only to address issues that had been creating tension, but to extend this mindset from intra-team communication to understandings of the perspectives of their external stakeholders. This demonstrates that empathy has a real contribution to make, not only in improving the workplace environment, but in uncovering hidden opportunities to increase productivity. These multiple impacts of empathy as a process and not just a sentiment, merit further research in the organizational context.

Carole Charland has a M.Sc. in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Montréal. She conducted research for more than 20 years, in program evaluation in Public Health before her career in market and organizational research. She conducts research at Sapiens Strategies Inc., she founded. carole.charland@sapiensstrategies.com

Karen Hofman has a M.Sc. in Cultural Anthropology and an graduate diploma in management and sustainability. She has been conducting ethnographic market research in the US, Canada and internationally for past 20 years. karen.hofman@sapiensstrategies.com

NOTES

Acknowledgements – Thank you to the reviewers and curators of EPIC, particularly Ryoko Imai for her careful reading, help, support and contagious enthusiasm.

REFERENCES CITED

Bourdieu, Pierre

1980 The Logic of Practice. Stanford, Stanford University Press

Brun, Jean-Pierre and Ninon Dugas

2008 An analysis of employee recognition: Perspectives on human resources practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(4), pp.716-730.

Defert, Daniel et François Ewald.

2000 The Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984. Vol. III: Power. New York: The New Press

Blache, Christine and Karen Hofman

2007 The Holistic Approach: Emphasizing the Importance of the Whole and the Interdependence of Its Parts. Market research best practice: 30 visions for the future; a compilation of discussion papers, case studied and methodologies from ESOMAR, ESOMAR World Research Publication, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Leeman, Ron

2016 Organizational Culture Change: What Is It Exactly and Why Is It So Difficult?, Organization, Change, & HR, March 2016 https://flevy.com/blog/organizational-culture-change-what-is-it-exactly-and-why-is-it-so-difficult/

Madsbjerg, Christian et al.

2014 The moment of Clarity: Using the human science to solve your toughest business problems. Harvard Business Review Press

Ben Messaoud, Nizar

2015 Performance Management 2.0: introducing the Behavioral Change Through Gamification-Framework. Master’s thesis. Strategy & Organization Program, Faculty of Economic Sciences and Business Administration, VU University, Amsterdam.

O’Connor, Malachi and Barry Dornfeld

2014 The Moment You Can’t Ignore; When big trouble leads to a great future. How Culture Drives Strategic Change. PublicAffairs, New York.