(This article is also available in Chinese)

Instead of asking how we can further speed up research itself, the question becomes how we can better integrate research into the product development practice and speed up organizations’ ability to learn and iterate overall.

For many years, insights was seen as peripheral to product development because of the perception that user research had low validity. I spent the first part of my career advocating for why teams should systematically listen to the people using their products, why anyone should trust qualitative insight to guide their decisions, and why research is a field of practice that requires specialized skills.

Debates about validity have diminished as the research practice has gradually proven its ability to contribute value. Approaching product making from the perspective of data, evidence, and empathy is pretty much a given these days. In companies such as Spotify, the pendulum has swung the other way, where growth in demand for research has pushed us to scale the practice. New, more substantive questions have emerged about our ability to produce value with speed that is compatible with the financial and competitive advantages of getting products to market quickly. User research especially, but also insights work more broadly, suffers from the reputation of being painstakingly slow—and there is merit to this argument.

As a community, user researchers across industry have taken on the critique and introduced a myriad of ways that allow us to shave off days or even weeks from studies. Used thoughtfully, all of these strategies speed up research without compromising the integrity of it:

- With research processes ranging from Rapid Iterative Testing and Evaluation (RITE) in the 2000s to guerilla testing and Google Design Sprints in 2010s, it has become a norm to run simple evaluative studies in less than 2 weeks.

- In-house insights organizations have developed team structures that make running research faster. A common approach in bigger companies (e.g. Spotify, Microsoft, Google) is staffing a team of researchers that run recurring research sessions on a weekly or bi-weekly cadence, combining research questions with narrow scope from around the company into a single study—with the intent of both democratizing access to user research as well as reaping the scale benefits from shared logistics.

- A key area of speed-focused innovation is participant recruitment, where companies, including Spotify, are building participant communities or panels that provide accelerated access to thoughtfully selected participants. Research vendors, too, are making fast access to participants a key value-add service to research tools such as survey or remote testing platforms.

- Finally, tools and processes are emerging that automate parts of the research process. Survey and card sorting platforms, for example, come with pre-vetted question and scale libraries as well as analysis and reporting modules. Research teams constantly iterate on streamlining their workflow as much as possible from note taking and reporting templates to collaborative analysis and debriefing formats.

Routine research is an optimized practice. The thing is, though, that much of impactful research is not routine and does take time.

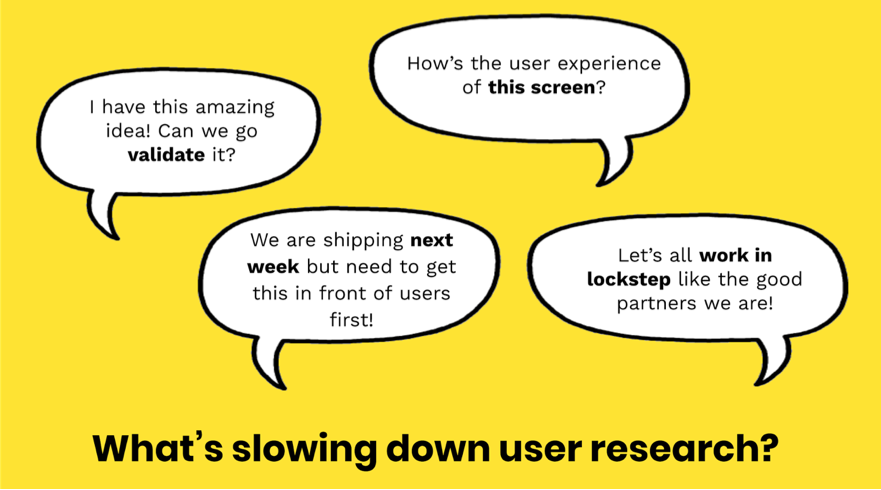

Joe Munko describes this fittingly: “When time constraints force us to drop the rigor and process that incorporates customer feedback, the user research you conduct loses its validity and ultimately its value.” Instead of asking how we can further speed up research itself, the question becomes how we can better integrate research into the product development practice and speed up organizations’ ability to learn and iterate overall. Ultimately, I see two root causes for slowness of user feedback loops: we treat user research as a gate to all decisions and we struggle when aligning research with agile product development cycles.

Stop Treating Research as a Gate

As user research has become a ubiquitous part of product making, we’ve begun to think of it as a deterministic prerequisite for all decisions. It is more productive to frame research as one of the inputs into decision-making, as well as a catalyst of culture focused on customers and people. Research does not have all the answers. I endorse the way Matt Gallivan encourages researchers to embrace the uncertainty inherent to their work. Within product teams, treating user research as a gate through which all products must pass creates a culture of unnecessary risk aversion. We end up running low validity research, researching the inevitable, and find ourselves myopically focused on user testing when other forms of evidence may be more appropriate or speedier.

Only run research that is valid. Researchers often feel it’s a betrayal of the practice or personal failing as a researcher to state that there are questions that can’t be answered in a robust way through qualitative research. This is the reason we end up running low validity research that slows down product development at best and leads teams astray at worst.

A premise for research that tends to trip up even experienced research teams is the attempt to validate strategic directions or specific concepts. I cringe at the idea of research as validation. Not only is this a strong indication that you are about to craft a research design that is prone to confirmation bias, you also ignore the fact that qualitative research is a very poor hypothesis testing tool and hence unable to confirm a product direction to be “the right one”. Instead, qualitative research excels in hypothesis generation and is helpful in identifying risks with a concept under evaluation.

Evaluate the risk of not running research. Over the years, a core part of any research role has been demand generation, and we often breathe a sigh of relief when appetite for research is strong. As a result, we end up running research to inform decisions that carry very low risk or, in some cases, are inevitable. This leads to a situation where feature teams are blocked from shipping as they wait for research to be run—often without having a clear conviction to make substantial changes even if the research indicates a need for it.

Organizations should create clear principles and alignment across disciplines in the product making team to consistently estimate the risk that is associated with each decision: e.g. Is this decision easily reversible if testing at scale uncovers issues? Do we have past research or other signals that reduce the risk associated with this decision? Do we have alignment on postponing the release to further iterate if we uncover risks? This helps you to evaluate the return on investment of each research initiative, allows you to spend more time on strategic research, and frees the teams to ship quickly when decisions carry low risk.

Consider the different types of evidence. Organizations with a track record of success using a specific insights methodology can easily fall into a pattern of applying a tried and true formula even when the research question is fundamentally different. This cognitive bias is known as Maslow’s Hammer—that is, when you have a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Organizations with strong user research practices have the tendency to see research problems everywhere even when another form of evidence—e.g. experimentation, competitive intelligence, or market research—would provide a better answer.

At Spotify, we’ve combined our user research and data science practices under the umbrella of product insights. You can read about how we’ve structured the practice here. I believe that mastery of diverse insights methods in a single team has yielded a more comprehensive understanding of our users. It has also made us more thoughtful about choosing methods most appropriate for the strategy or product decision at hand. This contributes to the speed of shipping in a couple of different ways. First, it helps with the two issues outlined above: we can avoid low validity research and mundane research when we add experimentation at scale and deep-dive investigation of product analytics to our toolbox. User research becomes the tool to identify appropriate hypothesis to test at scale, or a means of further investigating experimentation results we don’t understand. Second, it can help speed up research itself. Quantitatively identifying groups of users who interact with the product differently, for example, helps target the research to segments of interest.

Align Research with Agile

The cross-disciplinary operating models and rapid cycles of modern product development necessitate deliberate research timing—or insights will inevitably become a blocker. I wholeheartedly subscribe to both of the underlying beliefs of agile: diverse teams create better products and chunking problems down to their atomic components improves our ability to deliver predictably and quickly. However, these principles can be at odds with the natural scope and timeline of research.

Invest in off-the-shelf insights. Researchers who work on agile teams often find that the bulk of their portfolio is one-day studies just before or at the end of a design sprint. Not only is this a quite unsatisfying job for a researcher, but it also poses real risks to the research itself. Narrowly scoped research that sets a small product feature as the focal point creates an artificial setup for users, whose needs aren’t focused on a single screen or part of a flow. This increases the risk of skewed findings; consider, for example, studying popup notifications in isolation of a larger messaging system. Leisa Reichelt aptly describes this silo effect in her recent blog post. A narrow scope also reduces the lifespan of insights work as the findings end up being highly decontextualized from the larger user need or journey. I found Joe Munko’s characterization of wasteful, “disposable research” appropriate. Siloed research reduces organizations’ ability to accumulate knowledge. How is this related to speed? When an organization doesn’t have off-the-shelf knowledge it can tap to develop strategies or make reasonable hypotheses about its users, most initiatives big or small require new primary research.

Work ahead of the cross-disciplinary group. Becoming an instrumental member of a cross-disciplinary product development team is a big win for insights. I distinctly remember the time not so long ago of research as a service: work was taken on as requests from stakeholders or was initiated within a central research team but never really landed in the product-making process. It commonly suffered from the “not-invented-here problem” or was framed incorrectly due to researchers being too removed from the product team. That said, attempting to work in lockstep with a scrum team poses the challenge of research becoming a blocker as insights are often needed in scoping and planning stages of product initiatives.

Solutions we’re pursuing at Spotify to further our investment in both off-the-shelf insights and getting ahead with insights include changes to ways of working, planning structures, and team structures.

- Dual track insights process. I’ve asked my team to think about their work in any given quarter as consisting of two tracks: a foundational track that is motivated by the accumulation of lasting knowledge for the organization, and a shipping track that entails participating as required to provide inputs to decision making for their cross-disciplinary team.

- Learning OKRs. To ensure that the organization invests in lasting learning as well as plans ahead for the type of evidence, insights systems, or methods they need in a quarter or six months time, I’ve introduced the concept of learning objectives that are set as part of the quarterly OKR process. Through this mechanism, teams begin to reflect on learning as a deliberate investment similar to the investments that are made, for example, in tech platform. It also increases the buy-in to foundational research when the priority of learning OKRs are negotiated among cross-disciplinary leadership teams instead of pursued as insights passion projects.

- Combining embedded and centralized insights structures. We have introduced the concept of a strategic insights team that operates as a group of practitioners from both user research and data science backgrounds. We explore the organizational knowledge gaps outside of the short and mid-term product roadmaps. To avoid the classic central research team challenge of becoming disconnected from the rest of the organization, the centralized structure is experimenting with a timebank model where embedded researchers contribute time to the central team.

Conclusion

Improving the speed of research is a central challenge to insights organizations. There are several ways of optimizing routine research processes which don’t compromise the integrity but do shorten the cycle. Fundamentally, however, organizations should accept that research requires a level of rigor and time investment to be valuable. Instead of attempting to further speed up the research itself, organizations can increase the speed of learning by applying the following strategies:

- Stop treating research as a gate: stop treating research as validation, focus research resources to decisions that carry the highest risk for the organization, and consider forms of data that may be faster or more appropriate than qualitative research for the problem at hand.

- Align research with agile: shift investment from narrowly focused research to off-the-shelf insights, think of insights as a dual-track process consisting of shipping-oriented research and foundational research, integrate foundational research into the company-wide planning structures, and create flexible team structures which allow for foundational research that doesn’t suffer from being disconnected from product development.

References

Belt, Sara and Gilks, Peter. 2018. Cross-disciplinary Insights Teams: Integrating Data Scientists and User Researchers at Spotify. EPIC Perspectives.

DeCapua, Melissa. 2018. Life in the FAST Lane The successes, challenges, and influence of Microsoft’s quick-turnaround user research team. Medium, August 7.

Gallivan, Matt. Embracing Uncertainty in UX Research. Accessed Sept 29, 2019.

Munko, Joe. 2018. Skip User Research Unless You Are Doing it Right.

Reichelt, Leisa. 2019. Five Dysfunctions of ‘Democratised’ Research. Part 2 – Researching in Our Silos Leads to False Positives.

Toussaint, Heidi S. 2018. Rapid UX Research at Google.

Editor’s note: Spotify is an EPIC2019 Sponsor. Sponsor support enables our unique annual conference program that is curated by independent committees and invites diverse, critical perspectives.

Related

Breaking it Down: Integrating Agile Methods and Ethnographic Praxis, Carrie Yury

Scale, Nuance, and New Expectations in Ethnographic Observation and Sensemaking, Alexandra Zafiroglu & Yen-Ning Chang

Tutorial: Agile for Researchers, Carrie Yury & Chris Young

Panel: Ethnography in Agile Contexts: Offering Speed or Spark?, moderated by Martha Cotton

0 Comments