In this case study we use ethnographic outcomes from the study of the employee population of IBM, to inform new experiences for improving civic engagement in the resident population of Austin, Texas. In doing so, we experiment with a technique in speculative ethnography that uses research insights from a variant population with a variant challenge for in-depth explorations of a possible future. We demonstrate, first, that while in speculative thinking big ideas can be imagined, transposing ethnography enables a richer exploration of possible futures, and thus, further depth in ideas. And second, that by combining speculative thinking with existing ethnography, researchers and design teams can unearth bold experiments and jump start a design process that drives quicker learnings and impact in new contexts.

Keywords: Culture Change, Speculative Design, Civic Engagement, Design Research, Anticipatory Anthropology

INTRODUCTION

The largest scale problems in the world are often challenges of collective behavior. How do we change behaviors that affect climate change? That perpetuate gender inequality or racial bias? That hinder productive civic dialogue and participation? In this case study, we consider-culture change for the public good: improving participation in our democracy. More specifically, we tackle this challenge at the local level in our fair city of Austin, Texas, where, like in my other places in the United States, civic participation poorly reflects the diversity of the population.

The approach we use combines speculative design, ethnography and human-centered- design to propose radical solutions to Austin’s civic engagement challenges. In order to accomplish this, we draw from many years of research informing cultural change at IBM, in order to advance a cultural change mission in Austin, Texas. In juxtaposing these two change programs, we’re able to leverage both their similarities and differences to surface unexpected possibilities and interesting questions about what is given, what is ideal, what is likely, and what is possible. The result of this work is a very tangible set of outputs that help tackle the substantial challenge of how to change behaviors around civic engagement. In the process, we understand new ways to scale ethnographic insights about human behavior by re-applying them in new contexts, allowing us to address our world’s most wicked problems with deeper understanding.

PARALLEL PROJECTS IN CULTURE CHANGE AT IBM & IN AUSTIN

From 2014-2019 we worked as senior designers and researchers at IBM Design towards the explicit goal of creating a sustainable culture of design and design thinking, to help transform IBM into a more human and design-centered company, as a part of the Design Program Office (DPO).

To understand existing behaviors, how to best drive adoption of a new practice (Enterprise Design Thinking), and what conditions were needed to achieve both cultural and business impact, we worked through a multi-year longitudinal research study across the company. Methods applied include:

- Hundreds of hours of design studio ethnographic observations (14 studios studied globally)

- Multi-stage generative and evaluative interviews of product teams, consultants, sellers, executives and practitioners

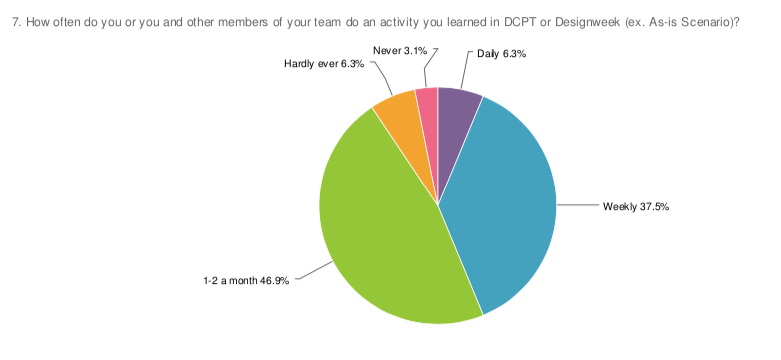

- Surveys of team members who had been trained 30/60/90 days out of training

- Participatory design workshops with experts within the business

Figure 1: Photos from various IBM Studios research trips

Figure 2: Example survey question and answers

IBM Key Insight #1 : Ecosystems of Adoption

At IBM, we learned that adoption of Enterprise Design Thinking1 was fueled by the presence of catalysts we internally dubbed “Magic People”—experts in the practice who could facilitate and encourage others, who were organically spread out around the business. But we saw they were drowning in the additional work of transforming the communities around them. They needed others, at various levels of expertise and authority to support their work.

These “Magic People” (and their needs) became the heart of the successful Enterprise Design Thinking ecosystem: EDT Coaches who could support and lead the Practitioners and Co-Creators around them, but be supported and protected in turn by Advocates and Leaders.

Figure 3: Enterprise Design Thinking badges system, designed in early 2017 (IBM.com/design/thinking)

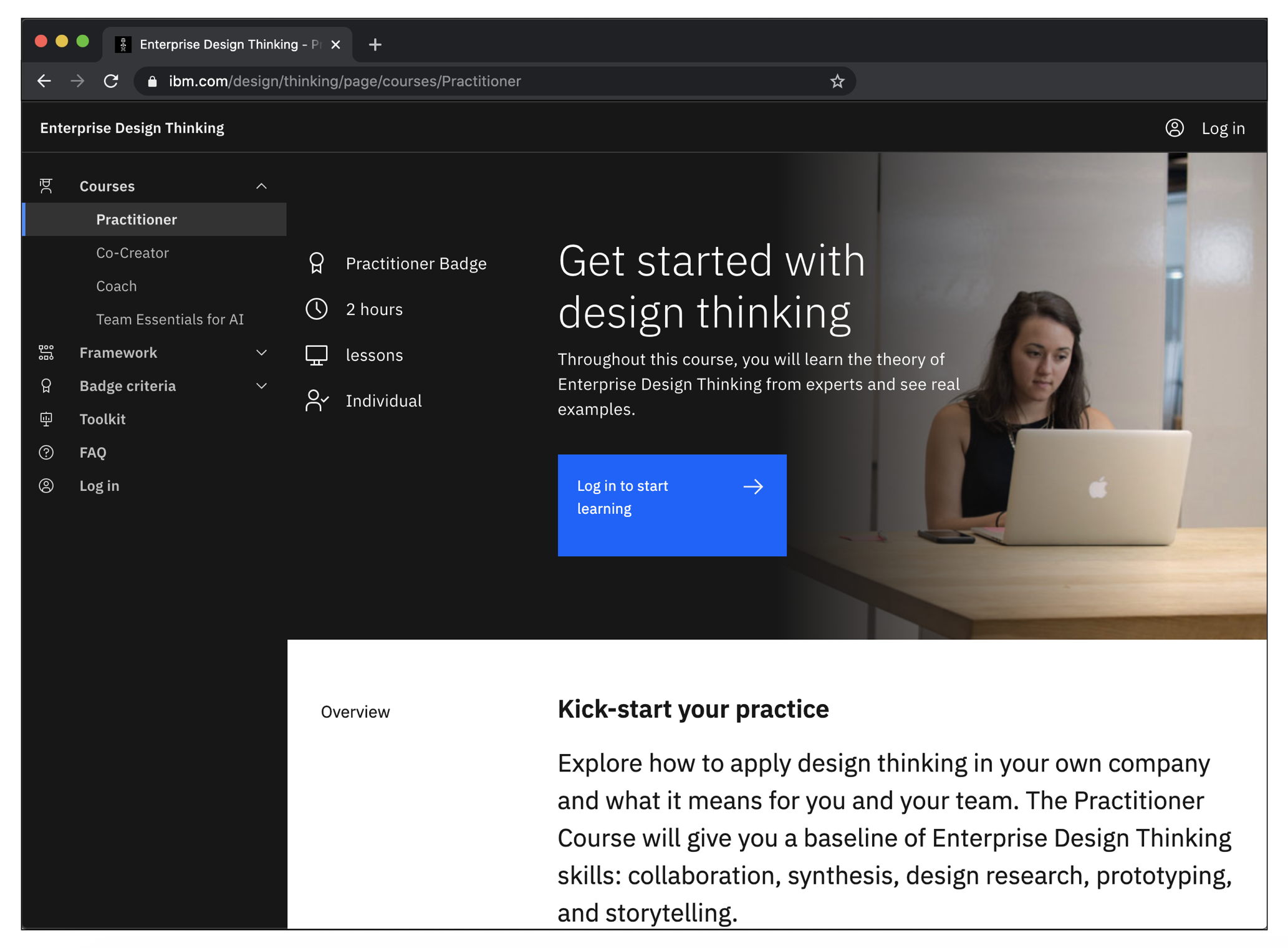

However, we also uncovered that we couldn’t just “train the trainer” and mass produce these “Magic People,” or even entry level practitioners. There was no time to educate every IBMer to the appropriate level with in-person learning—we needed to provide a journey and path for employees to move themselves from “level 0” to their appropriate place. Without such a path, it was too easy for motivated individuals and teams to stall and eventually become disillusioned at the total lack of change in their sub-communities. For the ecosystem to work, some would need to grow into advanced leadership levels, while many would become solid day-to-day practitioners, but they all needed to see the way forward and get education at each stop along the way.

This journey became the connective tissue between the digital badges, the surrounding context that informed desired ratios between the badge levels, and what enablement and resources were needed as IBMers progressed through their personal journeys.

Figure 4: Enterprise Design Thinking online learning modules (IBM.com/design/thinking)

IBM Key Insight #2 : Emergent Communities & Ownership

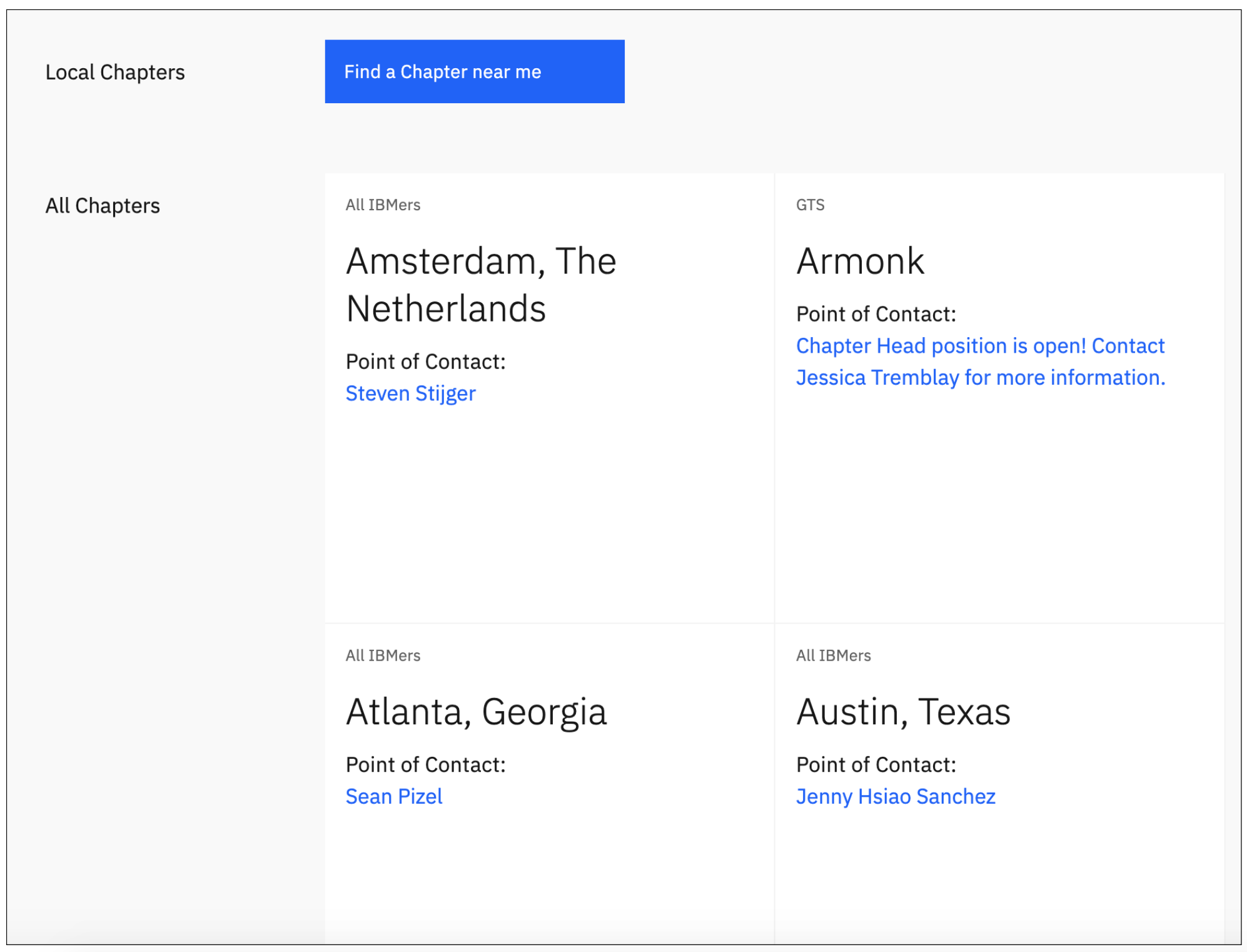

As we continued to observe the “Magic People” or EDT Coaches, we saw they needed to be connected together through a support system tied to a central community of practice where they could share experiences and bond. We also needed to help broadcast them to their local communities via what became a published set of EDT Chapters: decentralized hubs providing support and guidance leveling up, that were based on emergent communities spun up around known experts in various studios and geographies.

Often as existing experts, who were deft at nuanced customization of the practice within their specific business contexts, the EDT Coaches were both highly dependent on the centralized DPO for support, as well as resistant to its control and perceived oversimplification of technique. We found quickly that mandates don’t work very well even (especially?) in corporate environments. Something the Coaches knew inherently was that people need to see the value in their reskilling for their everyday activities, and then they will voluntarily reskill. For this reason, we didn’t use mandates very often to teach design thinking at IBM, but instead relied heavily on these sub-communities where personal relationships and local recognition pulled people into a transformational effort in a very intimate and human way.

Figure 5: In 2020, there are 105 decentralized Chapters in the network directory.

IBM Key Insight #3 : Studios & the Impact of Scaled Assets

Another component of our change program is “IBM Studios”—a global network of 50+ spaces designed to house designers and design thinking processes. Studios were designed for collaboration and thus feature open-office style seating and large spaces to host internal and external co-creation activities. We found that Studios served a dual purpose, not only as a functional change mechanism but also as an important symbol of change to both internal and external audiences. This symbol was instrumental for internal morale as well as for clients who couldn’t always see the day-to-day workings of IBM, but could visit a studio for a 1-hour briefing. For this reason, we took special care to recognize Studios as a symbol of the transformation, and so supported Studios in branding, creating visitor experiences and telling the unique story of each individual space.

The Studios became hubs for the use and distribution of assets produced by the DPO: educational materials, workshop decks, client references, books and toolkits, as well as the home for many of the EDT Chapters. We found repeatedly that these communities were hungry for reusable assets and so as a design team a key part of our work was identifying patterns of success, designing subsequent assets, and making them available to the global network. It was common for these branded assets to have a meme-like effect where they were used without meaningful knowledge of the underlying intention. We began to anticipate this outcome and considered this fact in how we designed and distributed assets.

IBM: IMPACT AND RESULTS

We’ve seen massive success in this cultural transformation. IBM tops the list of educated design thinkers at a single company with over 125,000 employees skilled up in Enterprise Design Thinking, and 20,000 formally trained designers. We’ve seen an 11+ increase in IBM’s NPS scores in 2019. Forrester reported faster, more efficient and higher quality outputs, documenting the impact of these new cultural processes2: product deployment on average 2x faster to market, a 300% return on investment and a 75% increase in efficiency.

What’s more, years in, we see the practice grow organically on its own, through human connections, an adoption that takes on a life of its own, and no longer depends on a centralized initiative. For example, the Enterprise Design Thinking Slack channel is the single largest at the company, boasting over 15,000 active members, and daily discussions on a wide variety of topics between IBMers who don’t typically know each other, or work together, but are deeply engaged in growing their individual, team and company practice.

The City of Austin: Creating a Culture of Civic Engagement

While big business is our day job, after the election, beginning in 2016, we had started a passion project: a mission based organization called A Functional Democracy, with our partner Amy Stansbury. Realizing the limited way that Austinites were engaged at the critical local levels of government, where we can actually make more impact on policy, regulations, and budget, we originally looked at re-designing resources provided by the city—resources that struggled to communicate immediate ways to participate, or the system of local government—without using insider language and ancient interaction paradigms.

Over time we evolved towards the mission of creating a culture of local civic engagement and activism. Through this work we empower local residents to take actions to make their city more directly reflect their needs and values.

Figure 6: A resource from the City of Austin website’s City Council Information Center (https://www.austintexas.gov/department/city-council/council/council_meeting_info_center.htm)

As we perused these two cultural transformation projects, the two worlds of IBM and Austin started to intermingle for us as researchers seeking to understand populations and their participation in new practices.

Despite the obvious differences between these two populations, there was one glaring similarity: they both had cultural transformations under way. They both needed to undergo change to redefine their ways of working to be successful in the future. Towards this end, in both cases we were educating and empowering people to change the cultures around them for their own benefit. And thus, as researchers, we were looking for insight into how these populations learn, how new behaviors are adopted in groups, how new memes spread, and most importantly—how to create these behavioral changes at scale.

What was the relationship between these two change missions and how could we leverage our 5 years of ethnography at IBM for the cultural transformation of the city of Austin?

“WHAT IF … ” SCENARIOS

As part of our design process for creating educational tools for Austin, we started giving ourselves the freedom to directly apply what we’d learned about culture change at IBM to explore ideas for cultural change in the city. Doing so cracked open opportunities, and helped us to think more expansively about how large populations learn and how we could empower people to adopt new ideas.

We began brainstorming ideas for Austin starting with a few simple what-ifs inspired by our work at IBM:

- What if, in the same way that IBM hired 2000 designers to kick-start its transformation, we hired 2000 full time “Civic Catalysts” in Austin that would funnel citizen voices into the system?

- What if, like how IBM built studios to foster collaboration, we built civic studios in Austin, that activists could use to work together and connect the dots between their different missions?

- What if, like how IBM built a pathway for Enterprise Design Thinking, we built a framework for civic engagement levels in the city that was so widely adopted that we could use it to measure and track learning?

The ideas that arose from this process were interesting to us because they hit a unique sweet spot between possible and absurd—a perfect combination for futurist thinking. We decided to treat these resultant scenarios as opportunities for Speculative Design. Speculative Design is a term coined by professors Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, and popularized in their 2013 book, “Speculative Everything: Design, Dreaming and Social Dreaming.” They describe Speculative Design as the following:

“[Speculative design] thrives on imagination and aims to open up new perspectives on what are sometimes called wicked problems, to create spaces for discussion and debate about alternative ways of being, and to inspire and encourage people’s imaginations to flow freely. Design speculations can act as a catalyst for collectively redefining our relationship to reality.” (Dunne and Raby, 2013)

Rather than simply treat these “What-if” ideas as metaphors, as in a “Big Idea” brainstorm3 where analogies are used as inspiration, we considered these “What-ifs” as real examples of how Austin might be in 10 years. These were possible futures that we wanted to explore in more depth.

Figure 7: In “What if” scenario 2 we questioned, “What if there were a framework for civic engagement levels for the city of Austin? And what if almost everyone in the city of Austin had a badge so that we could use this badging framework to recognize and track civic engagement?” (Source: “SXSW on 6th Street” by Ian Aberle via creativecommons.org and mediashift.org)

APPLYING SPECULATIVE ETHNOGRAPHY

In order to examine these what-ifs more closely, and actually move towards prototyping in the real world, we apply a method we call Speculative Ethnography, wherein we hypothetically “observe” human behavior in a speculative future for one organization (City of Austin) based on what we know about human behavior in the past from a second organization (IBM). We define Speculative Ethnography in the following way:

Speculative Ethnography is the informed study of how people could behave in future scenarios, based on what we know about human behavior in the present.

This approach of Speculative Ethnography is related to existing approaches that combine futures thinking and anthropological techniques including Ethnographic Futures Research (EFR), anticipatory anthropology and ethnofutures.4 5 These related disciplines or concepts use evidence from today to think systematically about possible futures.(English-Lueck and Avery, 2020)

This approach also has similarities to the practice of Ethnographic Analogy, commonly used in anthropological study, in which observed anthropological data from comparative populations is used to create hypotheses about past human societies. (Currie, 2016) While in Ethnographic Analogy parallels are drawn to reconstruct past human societies, in the process described in this case study, a parallel is used to construct future possibilities.

Figure 8: Two artifacts from ethnographic design futures work. On the left, a participant creates a rapid prototype of ‘personal experiential futures’. (Project design & photo: Maggie Greyson) On the right, Kelly Kornet creates an artifact based on research into the preferred future of an environmental activist. (Design & Photo: Kelly Kornet) (Source: Candy and Kornet, 2019)

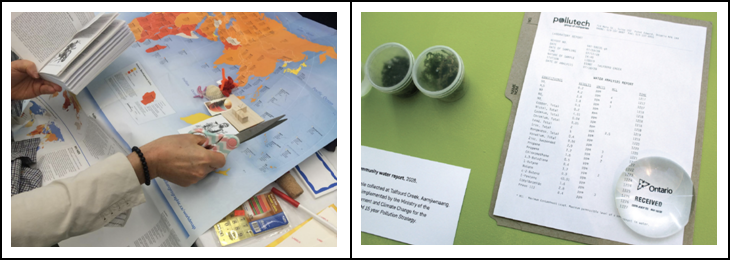

To explore this Speculative Ethnography approach we look to an analogy from Star Trek, the television show set in the 23rd century. One of the key features aboard the Starship Enterprise is the Holodeck. Through this device, participants ask a computer to craft virtual reality scenarios based on previous knowledge so that participants can experience these scenarios in an immersive environment. While this device is mostly used for entertainment, the show uses it to explore philosophical questions, and even solve problems in the real world.

In this Speculative Ethnography exercise, it’s helpful to imagine the what-if scenarios proposed as akin to the Holodeck. Using past ethnography as input, new scenarios can be created that rely on previous learnings. Via this method, ethnography is used twice in a recursive loop. First, to gather insights from a primary population, and then once a new “what-if” scenario is imagined, ethnography can be used to “observe” the secondary population. This method requires as input the in depth study of an existing population, and an analogous population.

Figure 9: The holodeck is a device from the television show Star Trek. With this device, participants may design and experience specific virtual reality environments. (Source: Screenshot via mediashift.org and screenshot via space.com and memory-alpha.fandom.com)

An Example of Speculative Ethnography

We’ve used this technique to inspire several projects in A Functional Democracy. Here we walk through one end-to-end example of how we have used this method in our process from speculated future to prototype.

At IBM, one of the most powerful change management techniques we created based off of ethnographic research was a learning pathway and badging system. By studying teams we observed that there was a natural ecosystem of design thinking skills and roles, that when at play, accelerated the successful adoption of a user-centered approach.

Transposing this idea onto the City of Austin, we posited: What if there were a framework for civic engagement levels in the city of Austin? And what if almost everyone in the city of Austin had a badge so that we could use this badging framework to recognize and track civic engagement? We put ourselves into the Holodeck and pulled out hypothetical learnings about this scenario, as illustrated below.

Hypothetical Observation #1

People are showing off their badges. They are proud of their status and make things like bumper stickers to represent their achievements. A counter-culture emerges that is anti-authority and vocally pushes back against the movement.

Figure 10: Illustration of opposing bumper stickers (Source: “Mur’s bumper stickers and plates, Raleigh airport, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA.JPG” by gruntzooki and “Twins” by dave_stone via Flickr)

Hypothetical Observation #2

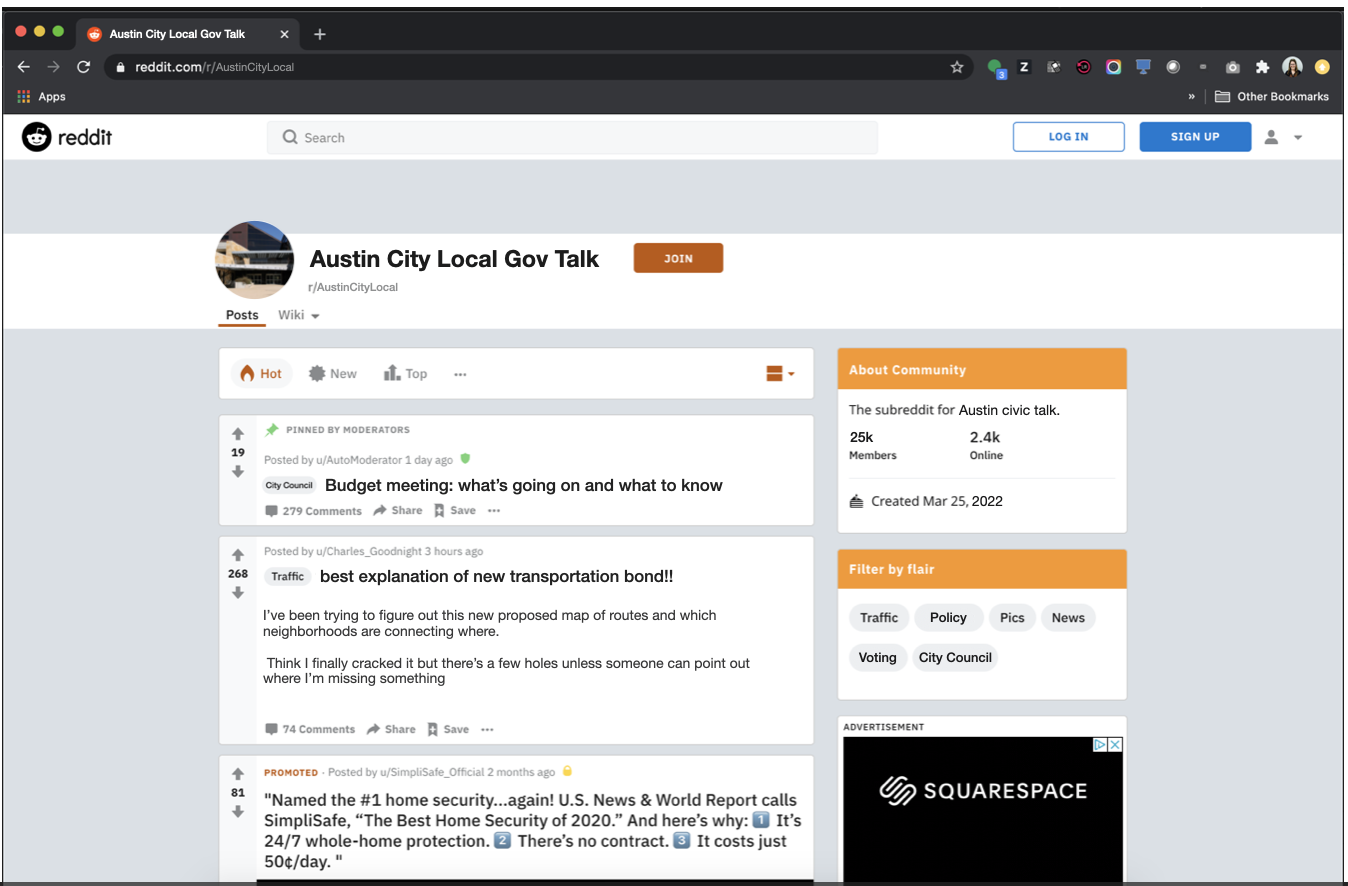

The official badging system leads to the organic rise of online communities in sub-reddits, informal Slack communities, and on Nextdoor. Residents discuss politics in a new way using their new shared language, all focused on building community around local civic engagement, decentralizing civics education as a result.

Figure 11: Illustration of local government subreddit

Hypothetical Observation #3

Residents eat up scalable assets. People share the assets freely and use them often, both for their own education and for evangelism. But the assets are also fetishized. They have a meme-like effect; the symbols are more wide-spread than actual change.

Figure 12: Illustration of the oversharing of the superficial symbols of the program (Source: “TouchID on Apple iPhone” by wuestenigel via Flickr)

Holodeck Insights and New Questions

As we play out this scenario, we are able to “observe” and examine the ideas in play based on what we know from these ideas existing at IBM, and develop hypotheses for how ideas would or wouldn’t work. We expect for example that some community figureheads (especially those who are experts in tangential disciplines such as advocacy, community organizing and activism) will view this new system with skepticism and want to align it to known frameworks. We expect novices who have been seeking guidance in this area, but feel stunted in their own practice, will gravitate to this framework immediately. We expect that they will share it widely and start to experiment with its activities to fit their own needs. We also believe that the accompanying educational materials and experiences, while communicating a serious, impactful message, must have a certain entertaining, fun, and human quality. (This might be obvious, but upon reflection of the current state of educational materials6 published by the city it has yet to be considered).

Through these observations we are presented with non-obvious new key questions such as what is the ideal ratio amongst levels of practitioners for the city to demonstrate a meaningful level of organizational change? How many novices to every expert is appropriate, etc.? And perhaps more interestingly: Will people adopt this without being mandated to do so?

These types of questions and synthesis in turn surface new hypothesis-driven ideas. For example, at IBM, the main incentive to “badging up” besides the implied better work output was largely social capital. As the goal is in both cases to grow skills outside of a centralized function of experts, beyond the recommendation of the CEO or trusted public figures, any mandates would have to come from smaller communities within the whole, and be a matter of personal pride.

APPLYING SPECULATIVE FINDINGS TO A SET OF PROTOTYPES

We followed this process to re-apply insights, ideate, observe, and draw out new insights over a wide spread of original IBM research, strategies and tactics. One of the persistent challenges of speculative work is how to turn this kind of thinking into real tangible actions; for our work at A Functional Democracy, the trick is weaving this speculative thinking into a traditional human-centered-design process. For all of the scenarios and subsequent evaluations proposed through this analog, the natural next step in a design process would be to prototype small versions of each idea or repeat the cycle as needed until a compelling enough set of insights is achieved.

In the case of the badges framework, we used our Holodeck insights as a hypothesis for the future, and went about creating a prototype to test out a version of this speculative idea today.

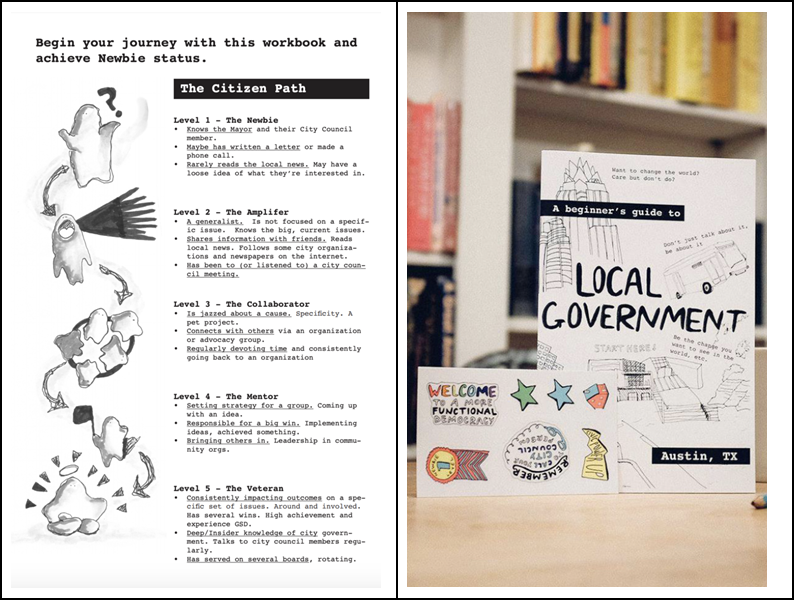

Civic Path and Shareable Assets

What we created first was a five level “Local Civics Path.” With this framework those at a “level 0,” desperate to become “level 1 Newbies” can immediately start to understand what they can do today to grow their practice as newly civically engaged, and also imagine a future for themselves at a more advanced level. We housed the framework within a ‘zine targeted at that exact first step.

Figure 13: On the left, an excerpt from the book showing the “Civics Path” from Newbie to Mentor. On the right an image of the ‘zine, “A Beginner’s Guide to Local Government”.

In order to create this framework, we started by sketching out draft levels based on expert interviews, and used them to source actual humans to flesh out critical behaviors and goals, further defining each level. Through this research we quickly understood that a baseline set of information (who the mayor and city manager are, how Austin’s city government is structured, who your city council person is) could quickly propel people into a personal civics journey, and that that baseline was nearly invisible to most. The ‘zine culminates in the “certified” levelling up for people to share socially as a marker of progress in order to empower those who self-educate and establish themselves as Level 1 Newbies.

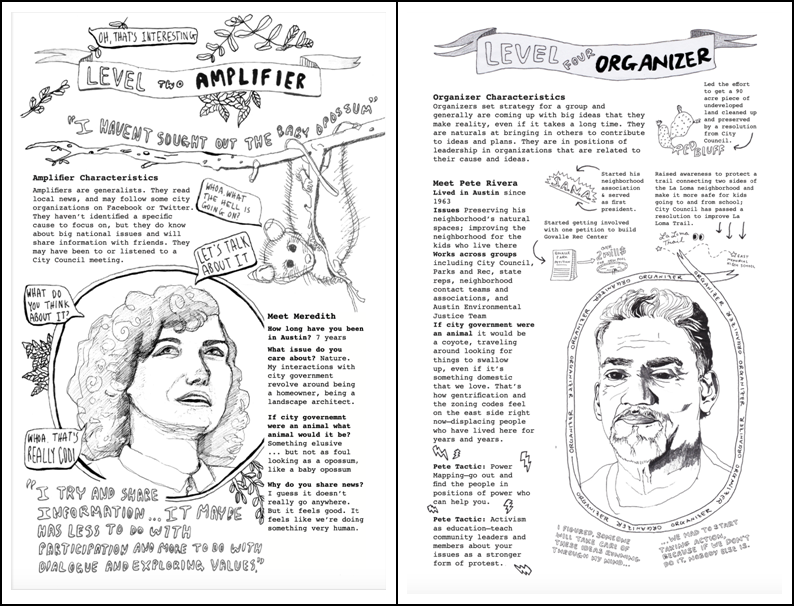

We also drew from our insights at IBM in creating the framework and ‘zine: we know new practitioners especially need to see the path ahead when growing a skill, with critical levels between where they are (essentially point 0) and what they see modeled by visible experts (usually levels 3+ on a 5 level scale). Importantly, they need to see this path marked by real humans with the details of personal stories to make it tangible and believable. So we included portraits of individuals at each step along the way to illustrate what it can look like to progress.

Figure 14: On the left, an excerpt from the book showing the “Level Two Amplifier” profile: Meredith. On the right an excerpt from the book showing the “Level Four Organizer” profile: Pete Rivera.

We made the book easy to produce and included stickers because we expected this scalable tool to generate excitement, and be widely shared. We made “call your Mayor” shirts but we only sell them with the book because there is a tendency to fetishize participation with an issue such as civic engagement. Both of these insights are pulled directly from the work at IBM. The speculative “observations” based on insights from IBM, gave us the fodder we needed to make a prototype and get started. We were able to do so with a confidence we would not otherwise have had, in a context where we had fundamentally less time, resources, and influence.

Early Impact and Results

Our prototype is in its early phases, but in two years we’ve gone from a first batch of 50 ‘zines to over 1,500 copies distributed and sold, with 3,000 more already funded. We’ve used the book to make in-roads with City Hall, received multiple grants, raised thousands of dollars, and partnered with huge organizations like Google, Facebook, AIGA, Austin Park Foundation and many others, to bring “Level 1 Newbie” education to new populations. We partner with other civics engagement organizations and initiatives such as the League of Women Voters and the Workers Defense Project as channels to distribute the ‘zine and its foundational education.

Here is a sample of user feedback on A Beginner’s Guide to Local Government:

- “I’m buying this book because I’m a small biz owner and a mom and want to make a difference.”—Austin Resident

- “I am buying this book because I feel pretty lost these days with regards to government and my role in it, and feel overwhelmed about the prospect of getting involved, but also no longer feel comfortable pretending I don’t need to be involved.”—Austin Resident

- “I bought this book because I don’t want to be passive and uneducated about this city that I deeply love and call home.”—Austin Resident

- “Ladies. Thank you so much. Your Beginners Guide to Local Government is seriously perfect. You don’t know how much you just inspired me and gave me hope and direction.”—Austin Resident

The material has spurred a relationship with City Council, and as the leaders of the city, we know from the analog that their buy-in and promotion of this education is key to its success in terms of driving a shared narrative around the value of civic engagement and how to engage. At IBM, we see business units with strong design thinking cultures stem from both the ground up as well as executive levels—individuals who are often closely related to the DPO and help contextualize its message into their own business case. In Austin, several members of council have promoted our content, and even spoken and participated at events that surround the book and serve as next level enablement. In 2019, for example, A Functional Democracy hosted an event at City Hall for Newbies to testify in front of City Council in a special session for the first time. Over 50 people participated directly with 5 members of council including the mayor.

Figure 16: Level 1 Newbies testify at City Hall for City Council for the first time

Other prototype materials are being tested including a series of next level (Amplifier) content to help the nascent population of civically engaged continue to grow, including in-person lectures, scalable video content, and stand-alone how-to guides. A round of Civic Catalyst prototype-roles were also tested in late 2019 where 10 individuals voluntarily worked with A Functional Democracy to promote the event at City Hall and drive awareness and skills growth in their personal networks.

The work in Austin by A Functional Democracy has drawn interest from local governments and civics groups in other cities. We now have a working model for enablement and growth that can be applied (with some local expert help) elsewhere. We have learned about how to scale a localized set of practice activities to other nodes in a system from our time at IBM that can inform a fresh set of “what-ifs.” The success of the prototypes to-date inspires us to continue to push the scale of the analogy, method, IBM insights, and potential growth of civic engagement outside of Austin.

LESSONS LEARNED: EMBRACING THE VALUE OF DIFFERENCE

When we started conceptualizing IBM outcomes as ideas that could be applied to Austin, we were skeptical about the value of the comparison. What could really be similar about two groups of people that seemed so distinct? The differences between these two organizations led to our deepest insights about human behavior and our most interesting ideas for change. Below are lessons learned from this case study.

Organizational differences exposed insights about common human tendencies in learning and adoption of new skills. For example, one might eagerly propose the idea of mandating the US population upskill their civics knowledge, but through reflection on IBM, we hypothesized that even if we could apply such a mandate it was unlikely to work. As a result, we were forced to jettison this easy fix idea and push ourselves to think of ways to drive adoption that involved incentivizing learning through the application to everyday life and existing social structures.

Ideas for the future that seemed “absurd” forced us to question axiomatic beliefs about Austin’s population. As a result new potential solutions were illuminated. For example, at a corporation, a natural solution to a culture problem is to re-skill the workforce or to hire people with a new set of skills. We wondered: Could we re-skill Austin’s population? Could we recruit people with civic skills to move to Austin? These were odd questions to ask about a city. What was it about a city population that made these proposals seem odd? Is it because it’s unnatural to “engineer” a population of citizens? Perhaps, but cities such as Austin frequently try to attract certain populations to drive their economies. Is it because wide-scale adult education is not perceived as a suitable role for the government? Perhaps, but cities frequently try to disseminate information to inform the residency. We found through this line of questioning that the original question was not actually the most interesting; instead, it is the line of thought that results in the question, “Why is this question strange?”

The freedom we allowed ourselves in this process expanded the role of our ethnography from primarily tool for understanding, to tool for exploring possibilities. When we started this project, we naturally thought to study each population independently. But through our comparison and the exciting ideas that resulted from our “what-if” scenarios, we were forced to re-imagine our ethnographic approach. What if the goal with this exercise of translating ethnographic insights wasn’t to be right, but instead to investigate possibilities? This mindset shift helped us transition from exploring the world the way it is, to projecting how the world could change.

CONCLUSION: SCALE AND THE ETHNOGRAPHY COMMUNITY

In this story ethnographic insights drive exploration into big, bold ideas about how to change our collective civic culture, starting in Austin but with potential impact for many other cities. Here the scale of impact is both about the scale of the problem, our national cultures around civic engagement, as well as the scale of the changes proposed—speculative ideas so different they seem slightly absurd. In this story, the tools of the ethnographer are scaled to a new population, to a bigger challenge and to bigger potential change.

In a world where problems are always wickeder and wickeder, analogous ethnography as a device for speculative design is just the toolset we need: it works to reveal the limitations of our imagination and the hidden structures that drive human behavior. Put in the hands of ethnographers, this approach is a way for us to explore the viability of alternative realities, gain insights into the nature of social structures, and to use those learnings to inspire systematic change in humanity’s largest populations.

Hal Wuertz is a co-founder at A Functional Democracy and leads design teams for IBM’s Artificial Intelligence Applications. Her previous paper, “Design Thinking for Change Management,” outlines a sample set of ethnographic techniques used in IBM’s cultural transformation. She holds a Masters of Architecture degree from Harvard University. hlwuertz@gmail.com

Jordan Shade is a co-founder of A Functional Democracy and leads design and human-centered strategy within IBM’s services organization. She has a master of design degree from the University of the Arts, sprouting from an interest in applied design thinking and research from her work with the Reggio-Emilia pedagogy. jordan.e.shade@gmail.com

NOTES

Immense gratitude to our EPIC editor, Scott Matter, for his insightful guidance in the construction of this paper. We would also like to thank our team at the IBM Design Program Office, especially our design research collaborators and design leaders including: Seth Johnson, Kathryn Millington, Nigel Prentice, Karel Vrdenburg, Erin Hauber, Mirko Azis, and Doug Powell. A special thanks to Phil Gilbert, General Manager of the IBM Design Program Office, for his mentorship, unparalleled leadership and sponsorship of design. And of course, thanks to our co-founder and collaborator, Amy Stansbury, for her endless knowledge and passion for local government.

This paper does not represent the official position of International Business Machines Corporation.

1. For additional information on Enterprise Design Thinking, visit: ibm.com/design/thinking

2. The Forrester Total Economic Impact™ Study (2018) can be found online at: https://www.ibm.com/design/thinking/static/Enterprise-Design-Thinking-Report-8ab1e9e1622899654844a5fe1d760ed5.pdf

3. In the activity, “Big Idea Vignettes,” participants use analogies to come up with unexpected ideas. (www.ibm.com/design) A similar technique is described by Ideo as “Analogous Inspiration” (https://www.designkit.org). In both cases, unexpected parallels are then used as inspiration for tangible, near-term ideas. As Ideo describes, for example, you may visit an Apple store when designing for people in difficult circumstances in order to get inspiration about how to create memorable customer experiences.

4. “Anticipatory anthropology can be variously seen as a mode of inquiry that occupies the space between the disciplines of applied anthropology and future studies. Philosophically, the anticipatory approach has deep roots in applied anthropology since the purpose of studying human experience is to improve the quality of human life in the future…. Academic or practicing anthropologists who actively consider future actions and consequences anticipate alternatives for various possible futures. These anthropologists map the implications of that flow logically or emotionally from observable practices.” (English-Lueck and Avery, 2020)

5. For examples of design futures projects that leverage ethnographic techniques, see Candy and Kornet’s 2019 paper, “Turning Foresight Inside Out: An Introduction to Ethnographic Experiential Futures.”

6. See for example, this material published on the city’s website explaining Boards and Commissions. (http://www.austintexas.gov/department/more-about-boards-and-commissions)

REFERENCES CITED

“Analogous Inspiration.” Ideo Designkit website. Accessed [September 26 2020] https://www.designkit.org/methods/analogous-inspiration

“Big Idea Vignettes.” IBM Design website. Accessed [September 26 2020] https://www.ibm.com/design/thinking/page/toolkit/activity/big-idea-vignettes

Candy, Stewart and Kornet, Kelly. 2019. “Turning Foresight Inside Out: An Introduction to Ethnographic Experiential Futures.” Journal of Futures Studies website. Accessed [September 26, 2020]. https://jfsdigital.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/02-Candy-Turning-Foresight-Inside-Out.pdf

Currie, Adrien. 2016. “Ethnographic analogy, the comparative method, and archaeological special pleading” Science Direct website. Accessed [September 26 2020] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S003936811500103X

Dunne, Anthony and Raby, Fiona. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Dreaming and Social Dreaming. MIT Press.

English-Lueck, J.A. and Avery, Miriam. 2020. “Futures Research in Anticipatory Anthropology.” Oxford Research Encyclopedias website. Accessed [September 26, 2020]

“Enterprise Design Thinking.” IBM Design website. Accessed [September 26, 2020] ibm.com/design/thinking

The Forrester Total Economic Impact™ Study (2018) can be found online at: https://www.ibm.com/design/thinking/static/Enterprise-Design-Thinking-Report-8ab1e9e1622899654844a5fe1d760ed5.pdf