In the last ten years, an eclectic mix of electronic nicotine delivery products (‘e-cigarettes’) and practices have proliferated in the US with little restriction, producing a vast array of vaping mechanisms, flavors, and styles. At the same time, anti-tobacco movements have targeted e-cigarettes as a threat to public health and advocated for restricting e-cigarettes in much the same way as conventional cigarettes. While anti-vaping proponents associated with public health movements have typically regarded e-cigarettes as primarily harmful products that should be suppressed, vaping advocates regard e-cigarettes as harm reduction products that should be readily accessible to smokers. Distrust between these two warring “sides” animates the controversy over e-cigarettes. In our role as researchers conducting a qualitative study on e-cigarette use, we encountered suspicion and anger from members of an e-cigarette forum who felt that pro-vaping perspectives were often misrepresented by researchers. As a result, we dropped our initial plan to host a group discussion of questions directly related to our study on the forum. Nevertheless, the incident illuminated how vaping advocates have resisted dominant narratives regarding tobacco and nicotine use, destabilized nicotine product categories and challenged interpretations of nicotine use that dichotomize pleasure and health.

Keywords: E-cigarettes, Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, Ethnography, Qualitative research, Public health, Digital ethnography, Credibility

At the outset of a study aimed at understanding e-cigarette use among young people, we wanted to experiment with conducting a group discussion with participants on an online e-cigarette forum, but we also worried about how we would be perceived in our role as researchers linked to a public health organization. The wars over e-cigarettes – their health effects, how safe they are, how they should or should not be regulated – had grown ugly, and we had seen colleagues harassed online or professionally sidelined because they were perceived as either too anti-vaping or too pro-vaping.

Our own position researching vapers’ perspectives within a public health framework trapped us between the “vapers” side (relatively pro-vaping, construes e-cigarettes as primarily reducing harm-reducing) and the “public health” side (relatively anti-vaping, construes e-cigarettes as primarily harmful)1. Acceptance by one side, it seemed, led to rejection by the other side. Ultimately our e-cigarette forum experiment failed, in part because of how users perceived our position in the conflict between vapers and public health. Nevertheless, the experiment also highlighted aspects of “carnival spirit” animating the credibility contest between the two opposing sides, and the challenge that vaping advocates have posed to conventional narratives about tobacco and nicotine products. In particular, our encounter with e-cigarette forum members points to vaping advocates’ “transgressive resistance” to institutional messaging about e-cigarettes, and their refusal to subordinate the pleasures of the “sensual body” to the austerely “ascetic body” (Lachmann, Eshelman, and Davis 1988). In order to approach these points, we will first need to summarize some recent history that shapes the dominant sides in the e-cigarette wars.

THE E-CIGARETTE WARS

Over the last ten years, the use of nicotine vaporizers (a product category also referred to as “e-cigarettes” or “electronic nicotine delivery systems”2) in the US has proliferated within a highly contested environment. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) blocked entry of these devices into the US on the grounds that they were unapproved drug-device combination products. After e-cigarette makers were granted an injunction against the agency’s ban, the FDA proposed new regulations extending its authority over nicotine vaporizers and other nicotine products that were not initially contemplated under the Tobacco Control Act. Although the FDA announced its intent to regulate in April of 2011, the regulations were only finalized in May of 2016, following protracted public comment periods that yielded little agreement in the battles between the pro-vaping and anti-vaping camps. At present, the new regulations are the subject of several lawsuits (Center for Tobacco Products 2016; Deyton and Woodcock 2011; Kirshner 2011; Swanson 2016).

Conflict over the meanings and consequences of e-cigarette use is reflected in disparate approaches to e-cigarette access both nationally and internationally. For example, while the FDA’s new regulations seek to curb e-cigarette access, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) has moved toward promoting e-cigarettes for smoking cessation and harm reduction (Food and Drug Administration and Health and Human Services 2016; NHS Choices 2015). Meanwhile within the US, controversy over tobacco harm reduction and e-cigarette safety has led to the creation of groups such as the Consumer Advocates for Smoke-free Alternatives Association (CASAA), which promotes e-cigarette access in the face of public health campaigns aimed at curbing e-cigarette use. CASAA and other vaping advocates have criticized mainstream health organizations including the American Lung Association and the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network for portraying nicotine vaporizers as a health threat virtually indistinguishable from combustible cigarettes, but have also recognized pro-vaping stances from organizations such as the American Association of Public Health Physicians (Nitzkin 2009; Noll-Marsh 2013b)

In California, which has long been a breeding ground for influential tobacco control policies, the divide over e-cigarettes is especially stark. Several milestones in changing social norms related to tobacco use have origins in California’s tobacco control movement, including laws that restrict smoking in public spaces, the publication of incriminating tobacco industry documents that had been hidden from the public, and the subsequent crafting of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement negotiated between US tobacco companies and attorneys general nationwide. Rooted in 1970s activism targeting “Big Tobacco,” California’s anti-tobacco movement is embedded in a dramatic history of “tobacco wars” waged by activists against a powerful and unscrupulous industry (Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights 2016; Buckley 2012; Davis 1992; Francey and Chapman 2000; Glantz and Balbach 2000).

In particular, support for anti-vaping perspectives in the California anti-tobacco movement (Davis 1992) may be shaped by the legacy of public health support for “light” or low yield cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) labeling of cigarette tar levels, begun in 1966 with support from public health officials, did not cease until 2008, as it became increasingly clear that light cigarettes did not substantially reduce tobacco-related harm. Meanwhile, internal industry documents revealed that tobacco companies had knowingly misled the public about light cigarettes for decades (L. T. Kozlowski and Abrams 2016; L. Kozlowski and Pillitteri 2001; Shiffman et al. 2001). Among some present day tobacco control activists, commitment to a tobacco “endgame” abolishing recreational tobacco products and an aversion to tobacco harm reduction measures may be an inheritance of this recent past. From this point of view, tobacco harm reduction is a disingenuous label for industry attempts to keep people using deadly products (Brownell and Warner 2009; Glantz and Balbach 2000; Hurt and Robertson 1998; Rabin 1992).

Nevertheless, California’s reputation as a center for technological and cultural innovation has also made it a fertile setting for the ongoing development of e-cigarette technologies and practices, with the support of California’s ubiquitous start-up and DIY/hacker ethos. Orange County, for example, is known for manufacturing e-liquid flavors and has been heralded as the “Silicon Valley of vaping, “ while the Bay Area is home to a series C vaporizer start-up known for its innovative e-cigarette designs, as well as DIY vaping and e-liquid enthusiasts (Vaknine 2015; Williams 2015). In an unrestricted, pre-regulation e-cigarette marketplace, the West Coast has emerged as a hotbed for the vaping industry (Groskopf 2016).

DAVID OR GOLIATH

As the regulatory environment evolves, it is unclear whether the challenge to public health officialdom posed by e-cigarettes will persist, or emerge as a fleeting Mardi Gras – one soon constrained by Lenten restrictions on a “vice” that had previously escaped bureaucratic control. Regardless, e-cigarette use has flourished during a period of suspended constraints, outside the reach of regulators and public health advocates who seek to restrict e-cigarettes in much the same way as conventional cigarettes. During this period in which e-cigarettes have broken away from the “usual rut” of the tobacco marketplace (Bakhtin and Emerson 1993), pro-vaping advocacy has also inverted conventional narratives about the health hazards of nicotine use, the dangers of smokeless tobacco, and who is the righteous underdog of the tobacco wars4. While the anti-tobacco movement sees itself as an array of nonprofits doing battle with Big Tobacco, the pro-vaping side sees itself as a collection of ordinary citizens and small businesses battling a public health funding apparatus that they believe protects the pharmaceutical industry’s investment in Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) products such as nicotine patches, nicotine gum and nicotine inhalers, as well as Big Tobacco’s monopoly on recreational tobacco products. Each side, therefore, sees itself as David to its adversary’s Goliath.

It was no surprise then when members of the online e-cigarette forum we approached did not greet us, the representatives of Goliath, with open arms. After negotiating approval and guidelines between both our Institutional Review Board (IRB) and a forum moderator, we introduced ourselves as researchers on the site’s welcome channel as requested of all new user accounts. The response we received to our introductory post was so overwhelmingly negative that we decided not to post our proposed thread with group discussion questions directly related to our study at all. Our experiment failed. And yet, as we listened to participants’ concerns and answered their questions about our motives, we became engaged in extended dialogue with several forum members and one moderator, both on our initial thread and through the site’s private messaging system. (Although nearly all of the forum members initially regarded us with suspicion, those we spoke to via backchannel seemed more open to dialogue, perhaps attributable to the intimacy of one-on-one conversation or an element of social pressure on the thread.)

Forum members inverted our typical practices through their vociferous opposition to our proposed research. In a reversal of the dynamic we often participate in as qualitative researchers, the thread’s participants essentially interviewed us, on their own turf. First and foremost, they sought to establish whose side we were on. E-cigarette research, they noted, typically has a “political stance.” On one side, they suggested, were those who believed that vaporizers can be useful as a less harmful alternative to combustible cigarettes and/or as a cessation tool. On this side, a forum member noted, researchers were “trying to prove what vapers already know.” On the other side, forum participants observed, were those who believed that e-cigarettes should not or cannot be used to reduce harm or for smoking cessation. On that side, forum members suggested, researchers exaggerated and misrepresented the potential harms of e-cigarette use. Much like Becker, forum participants’ comments suggested that “the question is not whether we should take sides, since we inevitably will, but rather whose side we are on” (Becker 1967)

Since our study received public health funding, we were perceived as having arrived at predetermined conclusions. No matter what forum members said to us, they feared, we would “twist [their] words.” As one forum participant explained:

After being burned several times by researchers…most of the user base is likely going to be extremely hostile toward anyone claiming to be researching vaping, so you probably won’t get a lot of volunteers.3

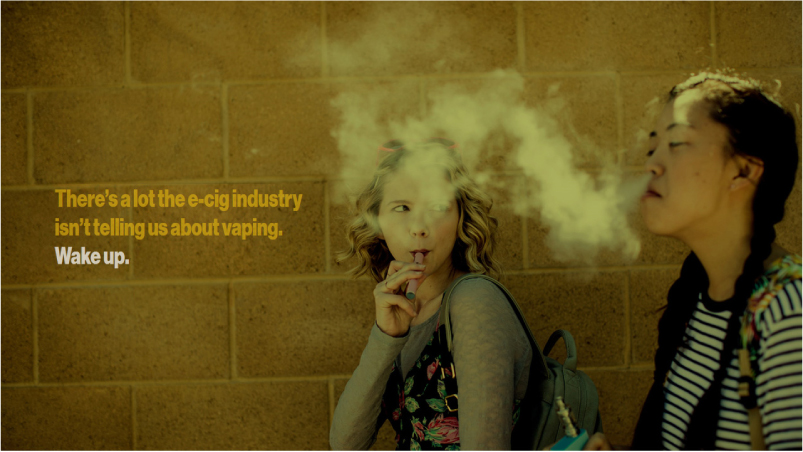

In addition, forum members regarded us as complicit in what they considered to be bad acts on the part of public health institutions. Among these bad acts was the California Department of Public Health’s mass media campaign “Still Blowing Smoke,” which forum members pointed to as a vehicle for misleading messages about e-cigarettes. Still Blowing Smoke is presented as a campaign against “the e-cig industry,” as shown in the campaign image below (Figure 1), reinforcing a hierarchy of credibility in which less credible information about vaping is attributed to industry.

Figure 1. “There’s a lot the e-cig industry isn’t telling us about vaping” (“Still Blowing Smoke” 2016)

Figure 1. “There’s a lot the e-cig industry isn’t telling us about vaping” (“Still Blowing Smoke” 2016)

In this campaign, the health department is looking out for the general public by protecting “us” from e-cigarette companies. Other messaging from Still Blowing Smoke suggests that, for example, e-cigarettes may pose equivalent or even greater risks than combustible cigarettes (“E-cig vapor can contain even more particles than tobacco smoke” (“Health” 2016). In addition, the campaign equates the e-cigarette industry with Big Tobacco, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. “It’s no surprise that Big Tobacco would be all over e-cigarettes” (“Still Blowing Smoke” 2016)

Figure 2. “It’s no surprise that Big Tobacco would be all over e-cigarettes” (“Still Blowing Smoke” 2016)

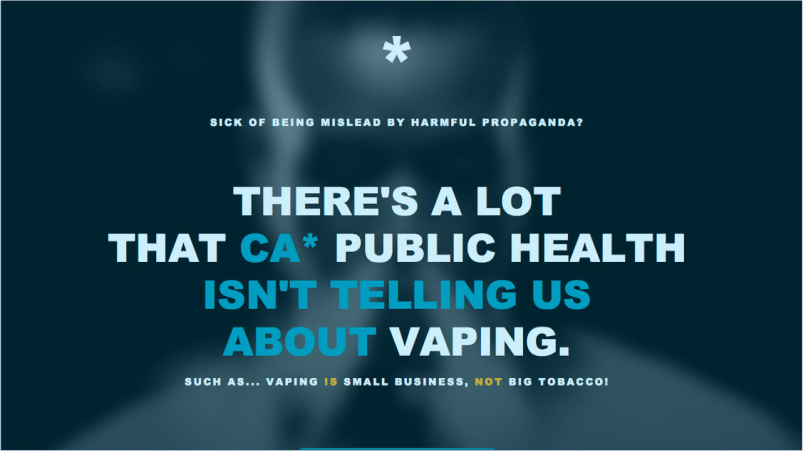

However, the forum members we spoke to saw their support for vaping as opposition to Big Tobacco. Vaping advocates have suggested that some of the restrictions forwarded by anti-vaping advocates will benefit Big Tobacco and disadvantage the smaller companies that initially dominated the e-cigarette market in the US. Thus messaging like that found in Still Blowing Smoke can read as support for Big Tobacco masquerading as opposition, whether wittingly or unwittingly. As a result, public health campaigns that take this approach are often parodied online. Still Blowing Smoke, for example, has a counter-campaign devoted to it called “Not Blowing Smoke” that challenges the original campaign’s credibility, as shown in the image below (Figure 3) from the counter-campaign’s website (“Not Blowing Smoke” 2016).

Figure 3. “There’s a lot that California public health isn’t telling us about vaping” (“Not Blowing Smoke” 2016)

Figure 3. “There’s a lot that California public health isn’t telling us about vaping” (“Not Blowing Smoke” 2016)

Since vapers associated us, as California public health researchers, with the “California public health” institutions referred to in the Not Blowing Smoke campaign as shown in Figure 3, they did not find us credible. From this perspective, California public health is a superordinate group of “of?cial and professional authorities in charge of some important institution” (Becker 1967) atop a hierarchy of credibility that relegates “us” – a general public seeking information about vaping – to a subordinate position. The Not Blowing Smoke campaign inverts this hierarchy by suggesting that public health institutions are not credible on the subject of vaping, and that vaping is qualitatively different from combustible cigarettes, i.e., vaping is “not blowing smoke.” As shown in Figure 4, Now Blowing Smoke frames “public health funding” as generating misinformation about vaping because researchers fear “losing their revenue from the harmful effects of… combustible tobacco products” (“Not Blowing Smoke” 2016).

Figure 4. “Vaping is only a hazard to public health funding” (“NOT Blowing Smoke” 2016)

Figure 4. “Vaping is only a hazard to public health funding” (“NOT Blowing Smoke” 2016)

The positioning of pro-vaping advocacy as David facing Goliath is further reflected in Not Blowing Smoke’s portrayal of its promotional strategies: Still Blowing Smoke is familiar to Californians as a mass media campaign that is disseminated through professional radio and television advertising and billboards in major traffic centers. Not Blowing Smoke, by contrast, presents itself primarily as a parodic website that started with “a $0 budget and small out-of-pocket expense,” and that is currently supported by a fundraising drive hosted on the crowdfunding site GoFundMe (Didak 2016, “Donate” 2016). Within this framing, Still Blowing Smoke represents mass messaging bearing the imprimatur of government institutions and promoted through conventional means, while Not Blowing Smoke presents itself as a carnivalesque expression of “nonlegitimated voice” (Quantz and O’Connor 1988), without institutional branding and circulated through personal social networks. Furthermore, by refusing the presumptive credibility of “public health,” this pro-vaping narrative expresses “disrespect for the entire established order” (Becker 1967).

Still, the different hierarchical models endorsed by Still Blowing Smoke and Not Blowing Smoke are mirror images of each other, with each side construing its opposite as a disproportionately powerful purveyor of discredited information. As Becker observed, in a setting of covertly political conflict, i.e., one in which one side’s superordinate status is undisputed, researchers are more likely to be accused of bias when they grant the presumption of credibility to the subordinate group’s narrative. (For example, Becker argues that researchers who grant prison inmates the presumption of credibility typically afforded to prison officials are likely to be accused of bias against prison officials, while researchers who grant this presumption to prison officials but not inmates are unlikely to be accused of bias.) However in the e-cigarette case, in which pro-vaping narratives openly challenge the authority of public health institutions, researchers are “in double jeopardy” of being charged with bias on both sides. The notion that “There’s a lot [they’re] not telling us” (See Figure 1 and Figure 2) highlights this potential jeopardy by implying that those who grant credibility to the opposing side are necessarily biased, or “seeing things from the perspective of only one party to the conflict” (Becker 1967).

MONOLOGUE OR DIALOGUE

In our own experience, it seemed that a corollary to “There’s a lot they’re not telling us” was “There’s a lot we’re not hearing.” In the polarized battle over e-cigarettes, the hierarchies of credibility in question were not only about whose narrative was perceived as more credible, but also about which narratives each side was even aware of and/or had access to. On one memorable occasion we attended a public health event where we heard multiple presentations emphasizing the dangers of e-cigarettes and the need to restrict access to vaping devices. As we listened to the event’s speakers, we were deluged with urgent messages from a number of email lists for vapers about the need to take action against an imminent development in e-cigarette regulation. As we were presented with these opposing perspectives on vaping simultaneously, we were struck by how disengaged each side seemed to be from the other. We were aware of no acknowledgment during the public health event of the upheaval happening among vaping advocates that day, nor did the presentations we attended address the pro-vaping arguments we heard most commonly from vapers online.

As a result, we wondered how much consideration or awareness some anti-vaping advocates were of divergent perspectives. Like our online forum participants, anti-tobacco movement activists too have been “burned several times,” not by researchers outside industry, but by sophisticated misinformation campaigns orchestrated by industry to misrepresent research and public opinion (Buckley 2012; Hurt and Robertson 1998). In some cases, for Perhaps due to reflexive avoidance of perspectives from the other “side”, the narrative of campaigns like Still Blowing Smoke is more “monologic” than “dialogic” (Bakhtin 1982; Bakhtin and Emerson 1993), bearing little relation to or comment upon the perspectives of those who argue against its messaging.

Conversely, the Not Blowing Smoke website reads as a response to Still Blowing Smoke; a satirical invitation to dialogue. Nevertheless, as was evidenced in our own e-cigarette forum experience, some vapers may reflexively discount the possibility of dialogue with individuals connected to public health institutions. Furthermore, grassroots players on the pro-vaping side, such as ordinary vapers and small vaping businesses, may have asymmetrical information access that can complicate perceptions of public health research and their engagement (or disengagement) with researchers. Access to paywall-protected research is perhaps the most obvious asymmetry between researchers and non-researchers. In the e-cigarette case, this asymmetry constrains assessment of competing claims regarding the potential health effects of vaping.

Paradoxically, asymmetrical attention resources, as opposed to information access (Goldhaber 1997), can also constrain engagement between researchers and non-researchers. In our encounter with the e-cigarette forum, for example, participants located abstracts describing our study on public health research-oriented websites. The public health research conventions employed in these abstracts took on a very different meaning when read outside of their original context, resulting in forum participants believing that we were biased against tobacco and nicotine users. Although much of our current research portfolio critically examines tobacco stigma, to participants it appeared that we uncritically accepted the stigmatization of smokers as beneficial to public health.

In particular, our use of the phrase “tobacco denormalization” came under fire, with one forum member observing that the phrase “comes off about as well as telling a more liberal-minded group you’re against the normalization of interracial marriage.” To tobacco researchers however, “tobacco denormalization” is a term that can encompass, for example, attempts to counter industry promotions that essentially amount to “Hey kids, smoking is cool!” – a message that nearly everyone we spoke to online felt should be countered. “Tobacco denormalization” can also refer to more stigmatizing anti-tobacco messaging like forum members objected to, but our use of the phrase was not intended as support for the stigmatization of smokers. Instead, we were describing the questions we would be addressing as framed by the literature in our field.

MEDICINE OR PLEASURE

In addition to challenging the hierarchy of credibility that frames anti-vaping narratives as more credible than pro-vaping narratives, vaping advocacy has destabilized conventional tobacco and nicotine product categories. Vapers’ objections to the language used in our abstract highlighted this destabilization, as some forum members took issue with the fact that our abstract appeared in conjunction with groups that classed e-cigarettes with tobacco products. To these vapers and other vaping proponents online, e-cigarettes are not tobacco. As illustrated by their contention, the meaning of “tobacco” is contested in e-cigarette discourse. Although this disagreement is sometimes presented as a clear divide between the two sides in the tobacco wars, in which one side interprets e-cigarettes as tobacco and the other side does not, the reality is more complicated.

Like medically-approved Nicotine Replacement Therapies (NRT) such as nicotine gum, nicotine patches, and nicotine inhalers, e-cigarettes are not used to combust tobacco, but instead provide nicotine in an alternative form. Thus, they are “not tobacco”, and vaping advocacy may also be considered anti-tobacco (Cahn and Siegel 2011). On the other hand, some vaping proponents have framed nicotine vaporizers as tobacco products based on regulatory distinctions (Noll-Marsh 2013a). These regulatory distinctions underline how tobacco and nicotine products are conventionally categorized. Although the FDA initially sought to regulate e-cigarettes as unapproved NRT products, the e-cigarette maker Sottera successfully argued that its products were marketed as recreational tobacco products rather than medical devices (“Tobacco Control Act Cases: Sottera Inc. v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration” 2010). As a result, the FDA’s new regulations deem e-cigarettes to be tobacco products.

Thus vaping advocates have suggested that e-cigarettes are not pharmaceutical products, but also that they are not medical products, destabilizing existing product categories. Furthermore, in challenging these categories, pro-vaping narratives have also questioned the dichotomizing of pleasure and health implicit in conventional models of medical and recreational nicotine use. Although NRT labeling requirements have recently changed in accordance with research suggesting that nicotine use in itself may not be particularly unsafe compared to smoking, nicotine use has long been constructed as the singular “health problem” of smoking. Following this framing, NRT is nearly equivalent to recreational tobacco use with a notable exception: smoking is more fun than NRT – and therefore more dangerous (“recreational” rather than “medical”). Pro-vaping narratives, by contrast, treat sensory pleasure and health-affirmation as mutually reinforcing rather than mutually exclusive. While anti-vaping advocates call for restrictions on e-liquid flavors just as there are restrictions on conventional cigarette flavors due to their appeal to children, the vapers we spoke to pointed out that “adults like flavors too,” noting that flavors helped them transition to less harmful e-cigarettes, or away from nicotine use altogether.

As regulation of combustible cigarettes moves toward increasingly utilitarian design and flavoring restrictions, e-cigarettes have exploded into a vast array of mechanisms, flavors and styles. While NRT offers little in the way of pleasure, vaping products cater to users’ desires, resulting in both risks (such as exploding batteries) and rewards (such as safety improvements and more satisfying devices) (Barbeau, Burda, and Siegel 2013; Dawkins et al. 2013; McQueen, Tower, and Sumner 2011). In particular, they cater to the desire for sensory satisfaction, including the “throat hit” that smokers may miss when using NRT. Amid a carnival of e-liquid flavors and personal vaporizer styles from minimalist to “blinged out,” as one forum participant put it, vaping has become a “performance of pleasure” (Presdee 2000), challenging perspectives that erase pleasure in the pursuit of medicalized treatment and/or optimal physical health (Bunton and Coveney 2011; Hunt and Evans 2008). By suggesting that nicotine products do not need to resist users’ sensual appetites in order to be beneficial or “anti-tobacco,” pro vaping narratives challenge the binary divide between cigarettes for pleasure and NRT for abstention.

WHOSE SIDE ARE WE ON?

As other scholars have noted, the environments in which researchers are working have changed since Becker asked “Whose side are we on?” (Becker 1967) Many of us do not work in ivory towers anymore, and many more who are in academia are no longer protected from the consequences of controversial stances by tenure (Warren and Garthwaite 2015). Outside academia, we compete for piecemeal grants, for industry or institutional jobs, and for contract work. Another recent change in research settings is broadening access to researchers’ processes and context collapse between professional and non-professional identities, as research practices become increasingly transparent and multiple facets of our lives are shared online, both by ourselves and by others (Marwick and boyd 2011; Wesch 2010). The increased transparency of research processes and the people who carry them out can facilitate questioning of the authority of research, giving people without official research credentials more direct access to research products for their own analysis and appropriation. While this increased transparency is ethically and pragmatically valuable, it may also require us to rethink who we write for in some settings. Working outside the ivory tower, working in an information-rich setting enlivened by social media, writing for multiple audiences, dealing with a highly polarizing topic – all of these factors can complicate researchers’ attempts to manage credibility, access, and the impact of their work. However, these factors can also afford us with enhanced opportunities to accommodate polyphony and dialogue. Given these factors, avoiding “the dungeon of a single context” may not only be preferable, but increasingly impossible (Bakhtin and Emerson 1993).

As qualitative researchers studying vapers’ perspectives and professionally connected with public health institutions, we have a pragmatic interest in negotiating credibility on both sides—but also a broader interest that may be central to our identities as ethnographers. The “with us or against us” stance that rendered outside perspectives suspicious makes it unusually difficult to maintain communication with both sides, but also highlights the value of the “in between” position of researchers who write about culture. Qualitative methods are particularly suited to this position due to their capacity to unearth conflicting points of view, multiplicity, and ambiguity (Antin, Constantine, and Hunt 2013). As our study has proceeded to another phase that includes in-person qualitative interviews with e-cigarette users from a wide range of backgrounds, we note also that while two sides have been highly visible in e-cigarette discourse, there are other sides. The pro-vaping and anti-vaping narratives we describe here appear to originate from relatively privileged groups on both sides. Online pro-vaping narratives seem to be forwarded primarily by white men, for example, while anti-vaping narratives have been disseminated by representatives of major institutions. Notably, third parties can be rendered less visible within contested narratives, as members of two dominating sides in opposition may be “unlikely to be placed in the position of being that third party” (Rodmell 1981). Given that “research is in all circumstances a political activity” (Warren and Garthwaite 2015), our “side” in this case does not aim to reinforce any particular hierarchy or polarized viewpoint, but rather to facilitate exchange across multiple voices and social positions.

Rachelle Annechino is an associate research scientist at the Prevention Research Center and a digital media specialist with the Critical Public Health Research Group.

Tamar Antin is a research scientist at the Prevention Research Center and director of the Critical Public Health Research Group.

NOTES

Research for and preparation of this manuscript was supported by funds from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP), grant number 24RT-0019. The content provided here is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of TRDRP. The authors thank Geoffrey Hunt, Sharon Lipperman-Kreda, Catherine Hess, Malisa Young, Emily Kaner, Emile Sanders, and Camille Dollinger for their comments on this draft and invaluable work on this project. We also thank Andrea Annechino, Jennifer Divers, Ella Ben-Hagai, Zoey Kroll, and the EPIC community for their thoughtful feedback.

1. “Vapers” and “public health” are labels often applied to the pro-vaping and anti-vaping sides, respectively. However, there are both vapers and public health professionals with stances that do not fit neatly into this divide. In addition, we note that the pro-vaping side often refers to anti-vaping side as “the e-cigarette industry” or “Big Tobacco,” but we have avoided this since the conflation of pro-vaping perspectives with industry is a point of contention.

2. We use “e-cigarettes” here because it is an umbrella term widely used for a range of products including cigalikes, vape pens, e-hookah, tanks and mods. However, some vapers use “e-cigarettes” to refer to cigalikes only, or object to the term “e-cigarettes” altogether. A common public health term for this category is “Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems” or “ENDS”, but we have largely avoided it here because it is not in popular use, and the acronym is not search-friendly.

3. Direct quotes used with participants’ permission.

REFERENCES CITED

Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights

2016 “A History of Advocacy: Defending Your Right to Breathe Smokefree Air since 1976.” Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights. Accessed July 23. http://no-smoke.org/pdf/historyadvocacy.pdf.

Antin, T., N. Constantine, and Geoffrey Hunt

2013 “Conflicting Discourses in Qualitative Research: The Search for Divergent Data within Cases.” Field Methods 27 (3).

Bakhtin, Mikhail

1982 The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist. Translated by Caryl Emerson. Revised ed. edition. University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail, and Caryl Emerson

1993 Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. U of Minnesota Press.

Barbeau, Amanda M., Jennifer Burda, and Michael Siegel

2013 “Perceived Efficacy of E-Cigarettes versus Nicotine Replacement Therapy among Successful E-Cigarette Users: A Qualitative Approach.” Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 8 (1): 1.

Becker, Howard S.

1967 “Whose Side Are We On?” Social Problems 14 (3): 239–47. doi:10.2307/799147.

Brownell, Kelly D., and Kenneth E. Warner

2009 “The Perils of Ignoring History: Big Tobacco Played Dirty and Millions Died. How Similar Is Big Food?” Milbank Quarterly 87 (1): 259–294.

Buckley, Christopher

2012 Thank You for Smoking. Hachette UK.

Bunton, Robin, and John Coveney

2011 “Drugs’ Pleasures.” Critical Public Health 21 (1): 9.

Center for Tobacco Products

2016 “Extending Authorities to All Tobacco Products, Including E-Cigarettes, Cigars, and Hookah.” WebContent. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. June 29. http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/RulesRegulationsGuidance/ucm388395.htm.

Davis, R. M.

1992 “The Slow Growth of a Movement.” Tobacco Control 1 (1): 1–2.

Dawkins, Lynne, John Turner, Amanda Roberts, and Kirstie Soar

2013 “‘Vaping’ Profiles and Preferences: An Online Survey of Electronic Cigarette Users.” Addiction (Abingdon, England) 108 (6): 1115–25. doi:10.1111/add.12150.

Didak, Stefan

2016 “GoFundMe: #NOTBlowingSmoke.” GoFundMe.com. Accessed August 8. https://www.gofundme.com/notblowingsmoke.

Deyton, Lawrence R., and Janet Woodcock

2011 “Stakeholder Letter: Regulation of E-Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products.” WebContent. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. April 25. http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/publichealthfocus/ucm252360.htm.

2016 “Donate.” Not Blowing Smoke. Accessed August 8. http://notblowingsmoke.org/donate/.

Food and Drug Administration, and Health and Human Services

2016 “Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. Final Rule.” Federal Register 81 (90): 28973.

Francey, Neil, and Simon Chapman

2000 “‘Operation Berkshire’: The International Tobacco Companies’ Conspiracy.” BMJ : British Medical Journal 321 (7257): 371–74.

Glantz, Stanton A., and Edith D. Balbach

2000 Tobacco War: Inside the California Battles. Univ of California Press.

Goldhaber, Michael H

1997 “The Attention Economy and the Net.” First Monday 2 (4). http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/519.

Groskopf, Christopher

2016 “What Yelp Data Reveal about the Sudden Rise of Vape Shops in America.” Quartz. February 10. http://qz.com/608469/what-yelp-data-tells-us-about-vaping/.

“Health.”

2016 Still Blowing Smoke. Accessed July 18. http://stillblowingsmoke.com.

Hunt, Geoffrey P., and Evans, Kristin

2008 “‘The Great Unmentionable’: Exploring the Pleasures and Benefits of Ecstasy from the Perspectives of Drug Users.” Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy 15 (4): 329–49. doi:10.1080/09687630701726841.

Hurt, Richard D., and Channing R. Robertson

1998 “Prying Open the Door to the Tobacco Industry’s Secrets about Nicotine: The Minnesota Tobacco Trial.” JAMA 280 (13): 1173–81. doi:10.1001/jama.280.13.1173.

Kirshner, Laura

2011 “Recent Case Developments: DC Circuit Rules FDA Cannot Block E-Cigarette Imports–Sottera, Inc. v. FDA.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 37 (March): 194–652.

Kozlowski, L., and J. Pillitteri

2001 “Beliefs about ‘Light’ and ‘Ultra Light’ cigarettes and Efforts to Change Those Beliefs: An Overview of Early Efforts and Published Research.” Tobacco Control 10 (Suppl 1): i12–16. doi:10.1136/tc.10.suppl_1.i12.

Kozlowski, Lynn T., and David B. Abrams

2016 “Obsolete Tobacco Control Themes Can Be Hazardous to Public Health: The Need for Updating Views on Absolute Product Risks and Harm Reduction.” BMC Public Health 16: 432. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3079-9.

Lachmann, Renate, Raoul Eshelman, and Marc Davis

1988 “Bakhtin and Carnival: Culture as Counter-Culture.” Cultural Critique, no. 11: 115–52. doi:10.2307/1354246.

Marwick, Alice E., and danah boyd

2011 “I Tweet Honestly, I Tweet Passionately: Twitter Users, Context Collapse, and the Imagined Audience.” New Media & Society 13 (1): 114–33. doi:10.1177/1461444810365313.

McQueen, Amy, Stephanie Tower, and Walton Sumner

2011 “Interviews With ‘Vapers’: Implications for Future Research With Electronic Cigarettes.” Nicotine & Tobacco Research 13 (9): 860–67. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr088.

NHS Choices

2015 “Some Types of E-Cigarettes to Be Regulated as Medicines – Health News – NHS Choices.” NHS Choices. August 27. http://www.nhs.uk/news/2013/06June/Pages/e-cigarettes-and-vaping.aspx.

Nitzkin, Joel L.

2009 “Joel L. Nitzkin Letter to FDA.” CASAA – The Consumer Advocates for Smoke-Free Alternatives Association. August 29. http://casaa.org/Other_Documents.html.

Noll-Marsh, Kristin

2013a “Are Nicotine E-Cigarettes a Tobacco Product?” Glimpses Through The Mist. July 25. http://wivapers.blogspot.com/2013/07/are-nicotine-e-cigarettes-tobacco.html.

Noll-Marsh, Kristin

2013b “E-Cigarettes: Rush To Regulate Could Destroy Effective Alternative.” CASAA. September 24. http://blog.casaa.org/2013/09/e-cigarettes-rush-to-regulate-could.html.

“Not Blowing Smoke.”

2016 Not Blowing Smoke. Accessed July 6. http://notblowingsmoke.org.

Presdee, Mike

2000 Cultural Criminology and the Carnival of Crime. London: Routledge.

Quantz, Richard A., and Terence W. O’Connor

1988 “Writing Critical Ethnography: Dialogue, Multivoicedness, and Carnival in Cultural Texts.” Educational Theory 38 (1): 95–109.

Rabin, Robert L.

1992 “A Sociolegal History of the Tobacco Tort Litigation.” Stanford Law Review, 853–878.

Rodmell, Sue

1981 “Men, Women and Sexuality: A Feminist Critique of the Sociology of Deviance.” Women’s Studies International Quarterly 4 (2): 145–55. doi:10.1016/S0148-0685(81)92918-3.

Shiffman, Saul, Janine L. Pillitteri, Steven L. Burton, Jeffrey M. Rohay, and Joe G. Gitchell

2001 “Smokers’ Beliefs about ‘Light’ and ‘Ultra Light’ Cigarettes.” Tobacco Control 10 (suppl 1): i17–i23.

Sottera, Inc. v. Food & Drug Admin.

2010 627 F. 3d 891. Court of Appeals, Dist. of Columbia Circuit.

“Still Blowing Smoke.”

2016 Accessed July 6. http://stillblowingsmoke.com.

Swanson, Ian

2016 “Lawsuits mount against FDA regs on e-cigarettes.” Text. The Hill. July 10. http://thehill.com/regulation/court-battles/287056-lawsuits-mount-against-fda-regs-on-e-cigarettes.

“Tobacco Control Act Cases: Sottera Inc. v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration.”

2016 Public Health Law Center at Mitchell Hamline School of Law. Accessed July 22. http://publichealthlawcenter.org/content/sottera-inc-v-us-food-and-drug-administration.

Vaknine, Lenny

2015 JUUL by PAX Review. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKhgncyDwnM.

Warren, Jon, and Kayleigh Garthwaite

2015 “Whose Side Are We on and for Whom Do We Write? Notes on Issues and Challenges Facing Those Researching and Evaluating Public Policy.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 11 (2): 225–37. doi:10.1332/174426415X14314311257040.

Wesch, Michael

2010 “YouTube and You: Experiences of Self-Awareness in the Context Collapse of the Recording Webcam.” Explorations in Media Ecology 8 (2): 19–34.

Williams, Lauren A

2015 “The Vape Debate: Is It Good or Bad for Orange County to Be the ‘Silicon Valley’ of Vaping?” The Orange County Register. September 15. http://www.ocregister.com/articles/vaping-682490-industry-liquid.html.