GSuite is changing the nature of Knowledge Work across 5 million businesses through AI-powered assistance. To ensure that this evolution reflects the aspirations and priorities of workers, Google and Stripe Partners conducted a multi-national ethnography of Knowledge Workers covering a range of industries. We identified that workers distinguish between ‘Core’ and ‘Peripheral’ work: the work they are paid to do and identify with, and the work that does not contribute to their success or happiness. Workers want assistance to enhance Core work and remove Peripheral work, nuanced across a spectrum of support. This framework and taxonomy has been adopted by teams at Google to inform strategic decisions on how AI is integrated by GSuite. New features are being implemented within Gmail, Slides, Docs and Sheets that bring these principles to life in the user experience.

INTRODUCTION

AI and automation are often spoken of as threats to human agency due to their potential to take over activities that humans are currently doing at work. In mainstream media narratives (e.g. Forbes, 2018) AI-based technologies are presented as something that is either present (and takes over) or absent (leaving humans in charge). This creates a false dichotomy and unhelpful distinction between the two states.

This paper is based on joint research conducted by Google and Stripe Partners in 2018. The objective of the research was to investigate the role of assistance, as idea and practice, in professional knowledge work. Data for this paper is derived from ethnographic interviews and workplace participant observation in several European countries.

Our research revealed the relationship between AI and workers is more nuanced than is often portrayed. We found that knowledge workers do not fear AI in of itself, but have a fine-tuned sense of how they want to perceive and experience its role in their work. These distinctions can vary between workers, driven by personal ideas of status, identity and professional responsibility.

The recommendations and insights informed both Google’s short term product strategy for G-Suite, as well as providing a number of foundational frameworks and common taxonomies that have been adopted across the organisation from leadership to different product teams.

OVERVIEW OF PROJECT

Research context

Recent reports (e.g. Davis et al., 2018) illustrate how the world of work is changing because of AI. Some jobs are being automated, while others are evolving. There are many technologies and services that are driving this shift. GSuite has been adopted by over 5 million businesses around the world, and the AI-driven features it integrates make it an important actor in this context.

Strategically, GSuite is focused on supporting the evolution of human knowledge work rather than automating it. GSuite’s stated mission is to elevate human accomplishment through machine learning augmented tools in the workplace. The objective is to help people to focus on their most important tasks, and, in doing so, enable companies to thrive.

GSuite is poised for the next wave of change in collaborative work. Individual contribution is almost always just one piece of a puzzle within complex knowledge workflows. The Google research team were looking to enable this collaboration not just within GSuite’s products, but across the products they use everyday.

Google believes that people should be able to collaborate in context, with Machine Learning and AI features built-in. Consequently, these capabilities should augment how people at work collaborate. This must be done responsibly and to the benefit of workers and businesses. Hence a focus on such tools is an opportunity of investment in Google’s customer’s employees and their company’s culture. Google also is aware that great care need to be taken when designing with AI Principles (https://ai.google/principles/) and Responsible AI Practices (https://ai.google/responsibilities/responsible-ai-practices/)

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

As researchers we realised we needed to dig deeper than these strategic principles to translate this vision of AI-powered work from the perspective of workers.

So we embarked on a program to understand the world of knowledge workers, exploring questions such as:

- what tasks in their everyday work do they value, which ones do they loath?

- which activities in their roles do they believe they give most value to their employers?

- what are the opportunities for G-Suite to provide Creative Assistance during the process of content creation: what types of work would people most appreciate having replaced or helped by AI?

Importantly, by taking a ‘bottom-up’ perspective the project sought to provide the team with an understanding of what assistance workers need today. This focus meant that resultant outcomes are designed to support existing working practices rather than replace them. Our research focus was therefore on incremental improvements to existing working practices, rather than analysing workers systematically to identify opportunities to fundamentally change or remove roles.

KEY OUTCOMES

The main contribution of the project within Google has been twofold (see more detail in ‘Implications and Impact’ section below)

- Embedding a new set of taxonomies and frameworks that inform AI-related decision making throughout the GSuite organization

- The frameworks outlined in this case study have been socialised across both the executive and product layers of the organisation, helping teams prioritise and develop strategies for integrating AI into their products

- Driving product innovation within specific GSuite teams

- Many product teams at GSuite (Gmail, Calender, Sheets, Docs) have now adopted these frameworks to inspire and guide how they integrate AI into their products, with many examples of new features already live

METHODOLOGY

Challenges to address

With a research brief to ‘explore attitudes to AI-assistance in professional knowledge work’ there was a significant methodological challenge for the research team in how to cover this topic that moved beyond existing tropes (both positive and negative) driven by the public discourse on AI and its potential role for work in the future. Researching technology that is not yet in (widespread) use is always a challenge as there is often no obvious existing behaviour to look at or existing preferences to discuss and explore. How is this possible to explore ethnographically? The problem is exacerbated because research participants could struggle to distinguish between prominent media-driven perceptions and the reality of their own behaviour.

Furthermore, knowledge work is a nebulous concept with ambiguous boundaries (Cross, Taylor & Zehner, 2018). Attempting to cover it in one research project is exceedingly difficult. It is broad in the range of people who do it (from secretaries to lawyers to nuclear scientists), in the range of activities it describes, in the range of (types of) organizations it takes place in and in the range of meanings attached to it. Academic research into knowledge work is typically either very abstract, looking to draw out general principles of knowledge work (Davenport & Prusak. 1998) or more narrow and not even attempting to say anything about the topic of knowledge work as a whole, but rather say something relevant about a specific type of work, workers or places. The challenge for this research was in doing ethnographically grounded research that would lead to insights with implications across the entire spectrum of knowledge work.

OUR RESEARCH APPROACH

Terms of reference

‘Knowledge Work’ was a term coined by Peter Drucker (Drucker, 1969). As commonly understood, it describes the growing cohort of workers who “think for a living”. Knowledge Work is therefore a broad category! Our study encompassed a range of knowledge workers: from designers to accountants to administrators to engineers to brand strategists. Nearly all our participants worked for large organizations and were primarily based in corporate HQs rather than remote working (although some remote working practices were observed). Within this, there was a mix of levels. We spoke to everyone from senior leaders to support staff. Everyone we spoke to existed within a wider team with whom they produced work collaboratively, although the frequency and intensity of collaboration with co-workers did vary across our sample.

‘Creative Assistance’ is a term used within Google to describe forms of AI that support knowledge workers within the GSuite product experience. This includes technologies that have been launched in the last 24 months such as Smart Compose in GMail (https://support.google.com/mail/answer/9116836?co=GENIE.Platform%3DDesktop&hl=en) and Suggested Layouts in Slides (https://support.google.com/docs/answer/7130307?visit_id=637038105256693940-2801069891&p=suggest_layouts&hl=en&rd=1)

Researching knowledge work

Highly skilled knowledge work is a complex process constituted by small tasks executed by individuals. These add up to larger tasks and workflows executed by multiple individuals, which lead toward desired outcomes. Researching such work requires mixed approaches in order to explore its complexity. For this research it entailed a combination of research with individuals and organizations.

Individual in-depth interviews

The researchers conducted a dozen in-depth ethnographic interviews with knowledge workers in the United Kingdom and Switzerland working across industries such as financial services, marketing, design and manufacturing among others. The individual perspective pursued in the interviews allowed the researchers to explore personal narratives around worklife, past, present and future. It also allowed for deep dives into actual work-flows with each respondent, which were essential in developing our framework for assistance, which will be discussed later in this paper.

Organizational ethnographies

To complement the individual perspective from the in-depth interviews the research also consisted of participant observation in three companies in Switzerland, an apparel manufacturer and a manufacturing services company, and in France, a gas company. By attending meetings, speaking to employees and colleagues working together, the organizational part of the research complemented the individual interviews in providing the organizational perspective of work. The organizational perspective lays both in the collective and collaborative work process that most knowledge work happens within and is constituted by, but also shows the role of tools and formal structures in how work is conducted. Seeing the formal structures of work within an organization also avoided over-emphasising the role of individual agency in doing work. The tensions that individual vs collaborative working modes surface in relation to personal assistance are discussed below.

Focusing on ‘assistance’ as a way into exploring AI

As discussed above, AI is a topic regularly discussed in mass media, often communicating strong claims about its potential role in changing the future of work. Against the background of such claims, having a conversation with a respondent about their own job and the potential role of AI in it risks becoming about public narratives of AI rather than the respondent’s own working reality.

To avoid this trap the research was framed around the concept of ‘assistance’ in the workplace. Assistance was consciously framed as tech-neutral and machine-human-neutral, i.e. assistance could be provided by a person or some form of technology, AI-enabled or not.

In essence, we explored instances of when people received some form help and support, and what kind of help and support they wanted or didn’t want in the future. This enabled the researchers to discuss work with respondents and draw out nuances around work the respondent does themselves, work where they get assistance from other individuals and work where they get assistance from technology. Importantly, it also allowed for discussing when and where respondents would like more assistance, from either another person or technology.

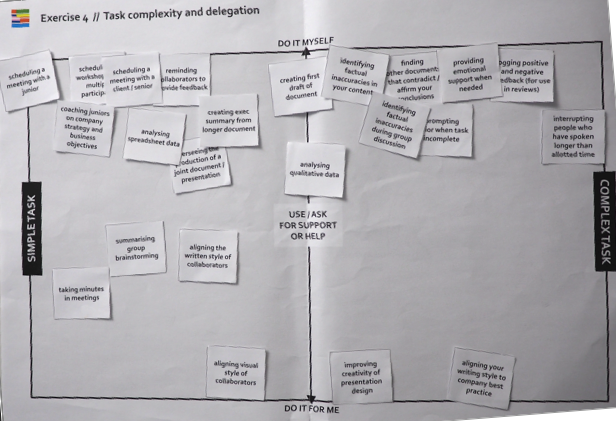

Figure 1. participant places tasks on a spectrum of support preference and perceived complexity (© Google, used with permission.)

However, from an ethical perspective we did not want to obscure the nature of our enquiry. So at the end of each interview we made the idea of machine assistance more explicit and encouraged a full and frank discussion about it. These discussions were informed by the previous exploration of assistance, meaning they were rooted in the reality of the individual’s work rather than existing media narratives.

Mapping workflows to reveal the reality of everyday work

Beside avoiding existing narratives overly influencing the research, there was also the difficulty of capturing the complexity of knowledge work with the limited time and methods at the disposal of the research team.

Most knowledge workers spend 40+ hours every week doing work. How is it possible capture anything tangible from such a mass of data? And how is it possible capture something beyond a superficial view of an individual’s work? The solution was to dig into specific projects, processes and workflow with each respondent. By taking a significant, ongoing task the respondent was currently involved in, the researcher could explore the various workflows involved and furthermore the smaller constituent tasks making up the workflow. The result at the end of the research was that the research team could map a number of very detailed workflows across time and tools used.

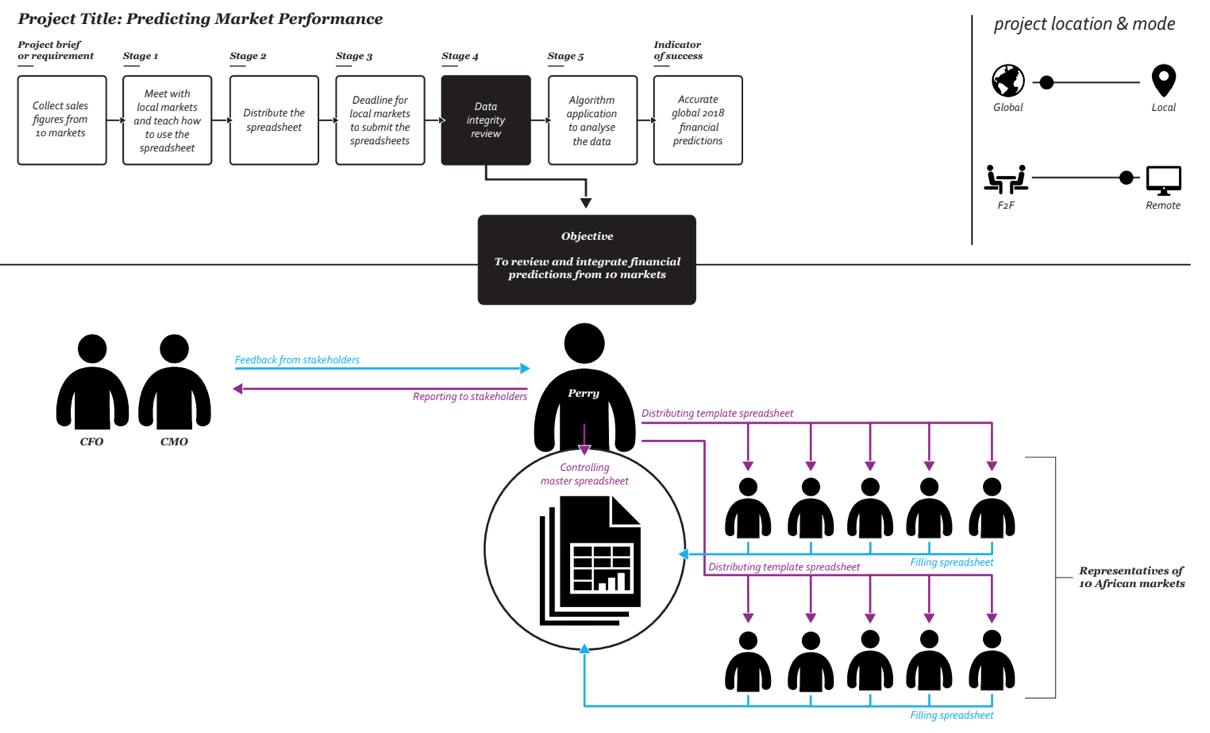

For example Perry, a financial analyst based in Zurich, was responsible for a routine but multi-layered piece of work every week: updating a financial forecast for the C-Suite in his organisation. To do this he required sales data from multiple co-workers spread across Africa to be delivered on time and in the right format. Every week Perry needed to manage and fix the same inconsistencies before he could generate the forecast. To him this was a waste of time. In the framework we subsequently developed, this is ‘Peripheral’ work.

Figure 2. Workflow mapping of Perry a financial analyst. (© Google, used with permission.).

CORE AND PERIPHERAL WORK

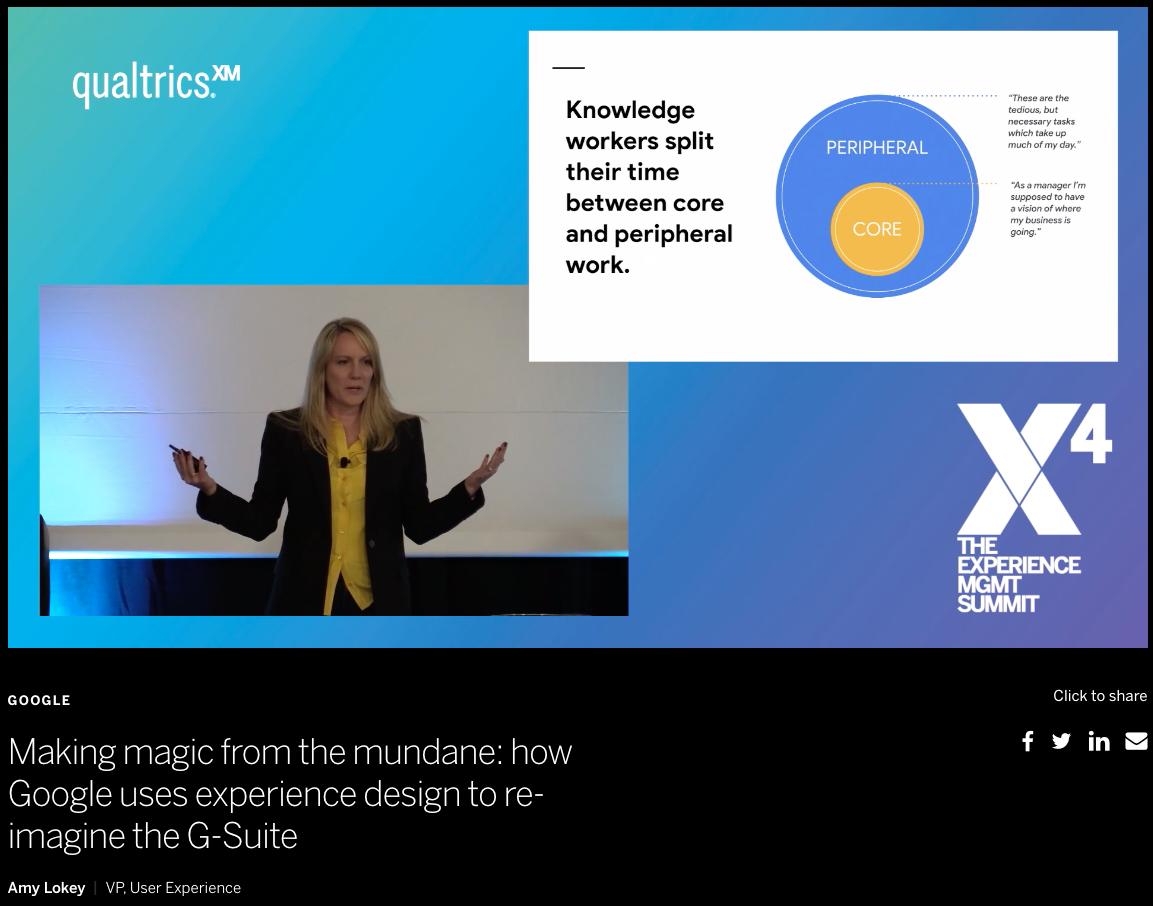

When observing and exploring everyday work a clear pattern emerged across all industries and roles. Workers days were split between a variety of activities, some of which they talked to as being core to their job, but the majority of which they talked about as peripheral.

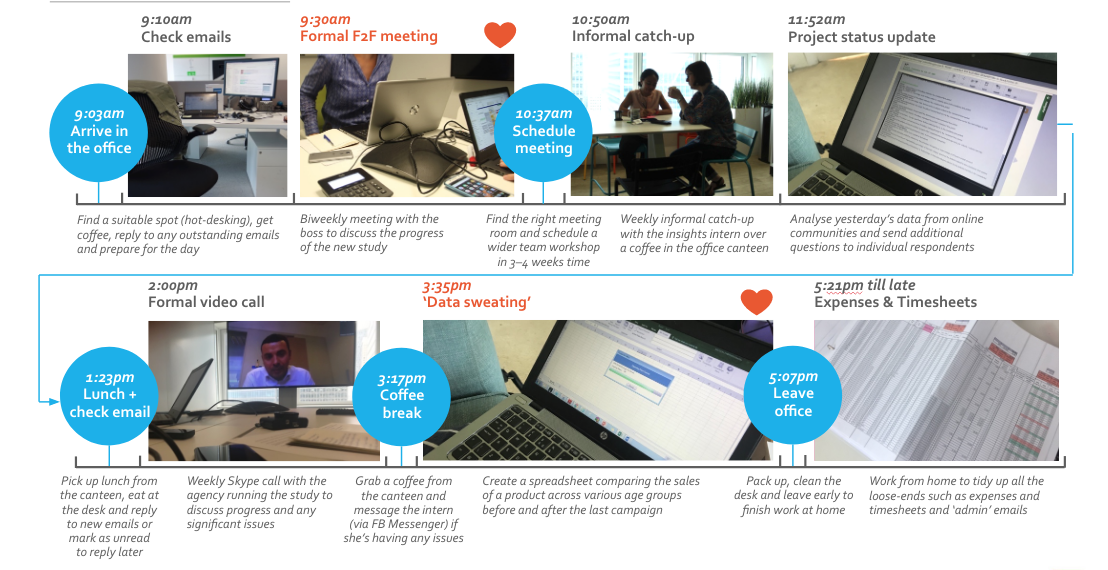

Tina, a researcher and analyst for a finance firm, represents a typical story from the study. A typical day consisted of three hours spent on ‘real work’ and five hours on tasks she regarded as peripheral.

Figure 3. Tina spends more time on Peripheral work than Core work. (© Google, used with permission.)

Defining Core Work

“As a category manager I’m supposed to have a vision of where the category is going and what the trends are”

Louise, Category Manager, global CPG firm

‘Real work’ is the work that is core to one’s job role, aspects of which are also core to one’s professional identity. Core work was described as the tasks and activities that directly contribute to achieving the aims of one’s job role. It is those activities that feel meaningful, that are part of your job description and that you get rewarded for. In other words, they are recognized by the employer as core to your role: it is what you are ostensibly employed to do.

Core work is often also core to your personal skill set and your professional identity, at least to the extent that you are in a job that matches your skills and experience. Thus, core work is not only core to the employer and job role, but it is also core to the individual worker as those tasks and activities that use your particular skills, where you get to use your skills and experience and where you can develop further within your professional field. As such core work is also central to the worker’s professional identity and career trajectory. During interviews it was often the tasks that individual workers wanted to focus more on and do more of.

Defining Peripheral Work

“My role is about dealing with people… but every time I travel I have to waste 2 hours filling in my expenses”

Alan, Project Manager, Gas Company

A large proportion of work that is only indirectly contributing to achieving the goals of one’s job. When asked respondents estimated the size of this more peripheral work to between 30% and 60% of their workday. While these tasks and activities only peripherally contribute to work goals, they are nevertheless important tasks that need to be done correctly. The risk of avoiding or delegating peripheral work can be high.

One recurring example of peripheral work was recording and reporting travel expenses. It does not contribute to the job goals of the person travelling, but is necessary for the accounting within the organization as a whole.

It also highlights a common characteristic of peripheral work, namely that what is peripheral to one person’s job is central to someone else’s job. In the case of travel expenses they are likely a core part of the job of someone in the accounting department of the organization.

Peripheral work, as tasks that do not directly contribute to your job goals, is also work you do not get rewarded for and rarely use your particular professional skills to do.

Davenport’s model of knowledge work

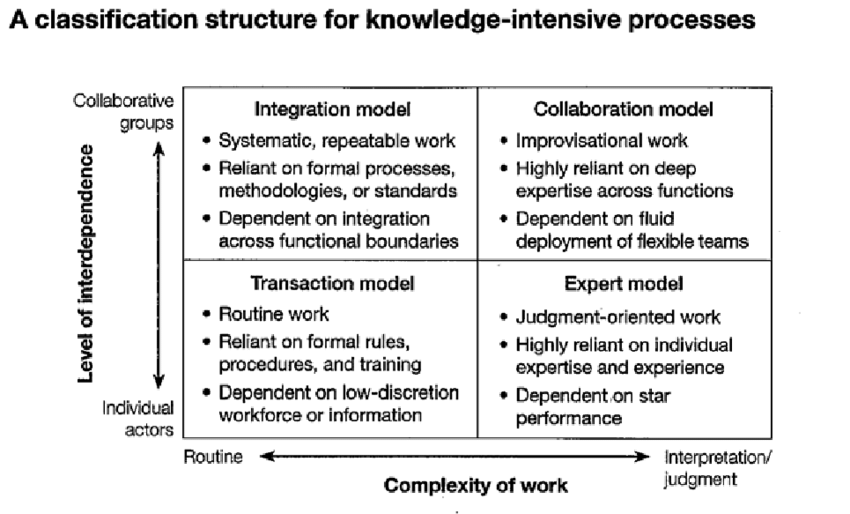

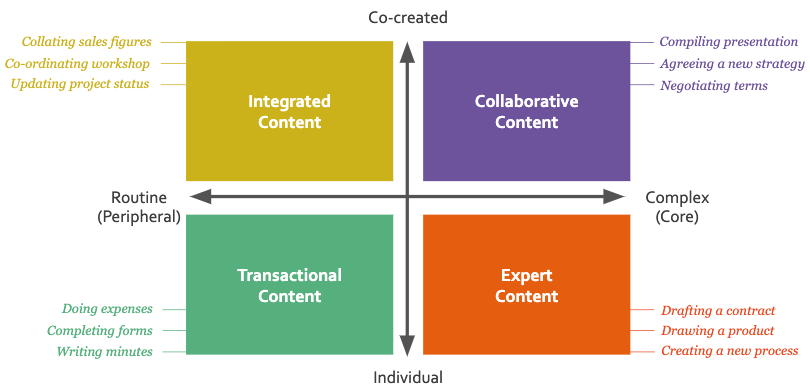

Business professor Thomas Davenport is one of the leading theorists of Knowledge Work and his “classification structure for knowledge-intensive processes” (Davenport, 2005) maps broadly to our conception of core and peripheral work.

In broad terms core work maps to Davenport’s concept of “interpretation / judgement” work, while peripheral work reflects “routine” work. However, Davenport’s model is a more accurate mapping of knowledge workers aspirations than the reality of their core work. Often key responsibilities were routine and, in a technical sense, were therefore core. However, most workers we spoke to intended to increase the proportion of “interpretation / judgement” work that was core to their job. This became an important factor in defining how workers wanted to experience assistance at work.

Figure 4. Davenport’s model of Knowledge Work (Davenport, 2005)

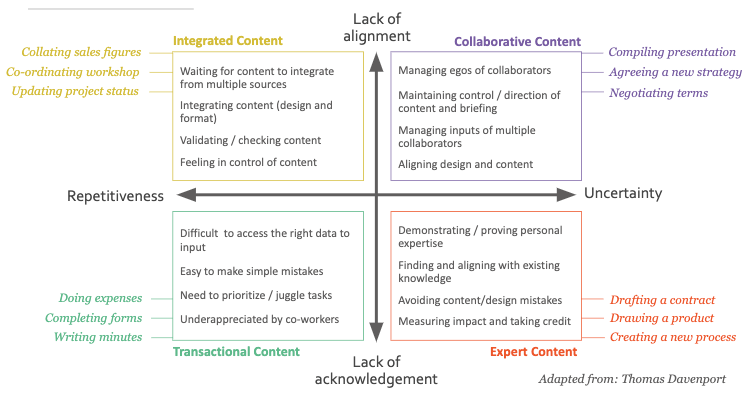

Using Davenport’s model we developed a framework which helped us to categorise the different forms of work we were observing and how it is experienced by workers. This, in turn, mapped to our core-peripheral model, with routine work generally mapping to routine work and complex work mapping to core – with some important exceptions which related to job role.

Figure 5. Adaptation of Davenport’s framework based on primary research. (© Google, used with permission.)

We then identified common pain-points using this model which helped Google teams to apply the model of assistance detailed in the next section.

Figure 6. Barriers to content creation across content types. (© Google, used with permission.)

WHAT (EXPERIENCE OF) ASSISTANCE DO WORKERS WANT

Mapping the core-peripheral distinction to assistance

The core-peripheral distinction and Davenport’s model of knowledge work allowed the research team to start making sense of the experience of knowledge work. However, by itself it didn’t explain the support people wanted from AI or human assistance.

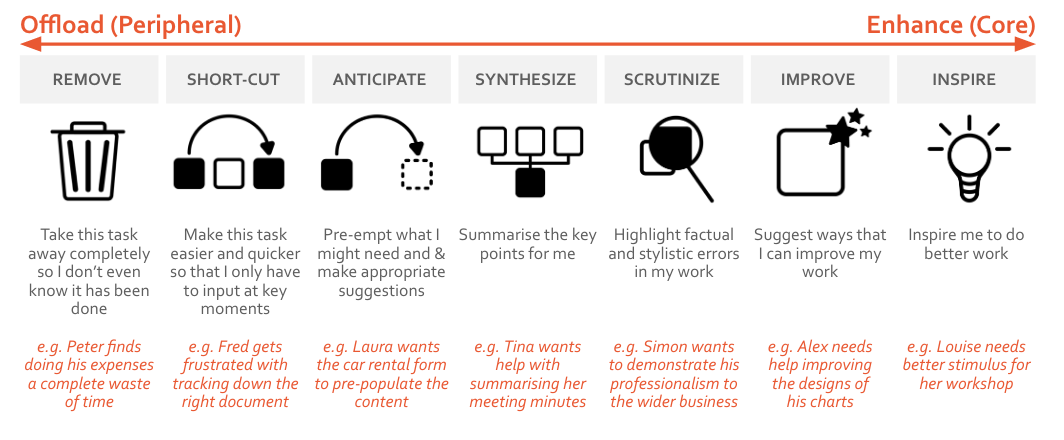

When discussing assistance, respondents expressed clear preferences for receiving different kinds of assistance depending on the type of task they received assistance with. The more peripheral a task was to them, the more they wanted to completely offload it from their responsibility. With core tasks, on the other hand, respondents preferred assistance that enhanced their execution of the task, without removing it from their oversight.

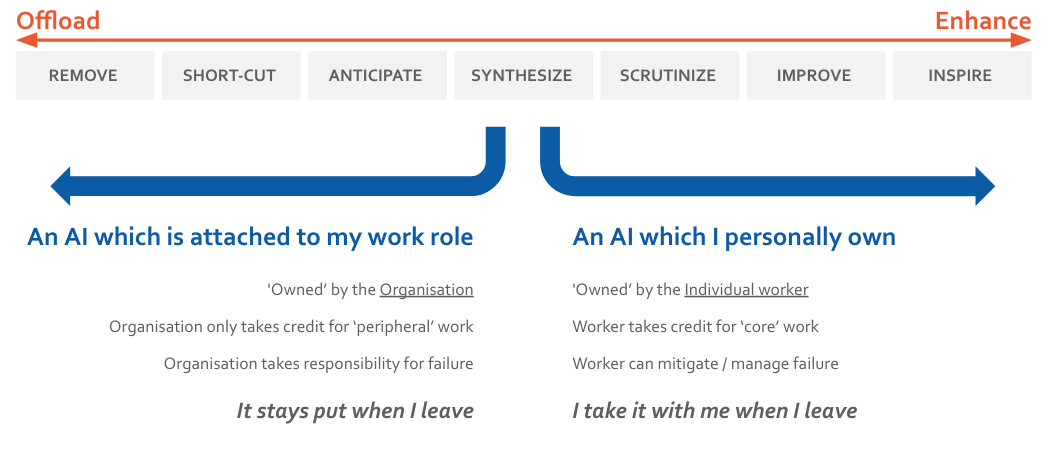

Seven specific types of assistance emerged from our research: remove, short-cut, anticipate, synthesize, scrutinize, improve and inspire. They can each be placed on the spectrum of assistance between offloading assistance and enhancing assistance. The following chart illustrates this with specific examples.

Figure 7. Spectrum of Assistance. (© Google, used with permission.)

Offloading peripheral work

“I feel more busy than I should be… I get 100’s of emails a day and most of them are bulls*!t”

Ingrid, Analyst, International Bank

As Ingrid illustrates, offloading peripheral work is often less clear-cut than outsourcing expense claims. The spectrum reveals that the experience of assistance that workers require is nuanced and can vary task-to-task within a workflow. Offloading does not necessarily mean total removal of the task; it can also be about speeding up the task (short-cut), pre-empting what is required (anticipating) or simplifying complexity (synthesise).

As discussed earlier, just because workers are not always rewarded by (or find meaning in) peripheral work this doesn’t mean it’s not significant and high risk. Ingrid’s ‘bullsh*t’ emails still require a thoughtful response. But if how she arrives at that thoughtful response can be expedited then that would be of immense value to her.

Importantly for peripheral work, it’s not critical for Ingrid to feel a sense of personal agency over the task. She doesn’t need to know or understand how the assistance works, and she doesn’t need to take credit for it, she only cares that it’s correct and produces a satisfactory outcome. Ironically this means that trust is a more important factor for peripheral work even if it is regarded as lower value work. This is because if the worker is willing to relinquish oversight they must place more trust in the agent that is working on their behalf.

Enhancing core work

“They employed me for my personality and for my thinking. You can’t teach strategic thinking — you either have that type of brain or you don’t”

Peter, Strategist, global CPG firm

Unlike peripheral work, core work is directly linked to how worker performance is measured, and often to their sense of value, identity and self-esteem. Because of this workers want to feel like they are in total control of all work they define as core.

In Peter’s case, he feels like he is employed because he has the ‘type of brain’ which is uniquely suited to his role. It is clear he derives a significant amount of self-worth from his belief about his skills, so any task which truly utilises them – such as developing a recommendation a new direction for a brand – must be responded to entirely by ‘himself’. Any form of assistance received during the execution of these types of tasks must be experienced as an augmentation or extension of his own capabilities. If he felt these tasks were being done ‘for’ him this would not only, in his view, dilute the quality of the work, but pose an existential threat to his personal sense of value. Peter is open to his work being ‘scrutinized’, ‘improved’ and even ‘inspired’. But it ultimately must remain his work, and by asking for assistance this must never be called into question.

There is a tension inherent in the concept of Core Work. As work becomes more collaborative it becomes more difficult for individuals to define and account for their specific contribution, reducing feelings of agency and ownership. For example, we noted a desire from several participants for an ‘audit’ trail for content they have personally contributed. Often as content is shared throughout an organisation individual contributions become adapted and merged into larger documents. It therefore becomes very difficult for an individual to know the impact their contribution is making and, by extension, take credit for that impact. Potential design implications of this for AI are discussed below.

Interestingly, even though core work is of higher value to the worker there is less need for them to trust the assistance they receive. Because workers want to remain deeply involved in their core work they have more capacity to evaluate, accept or dismiss any assistance that they solicit or receive.

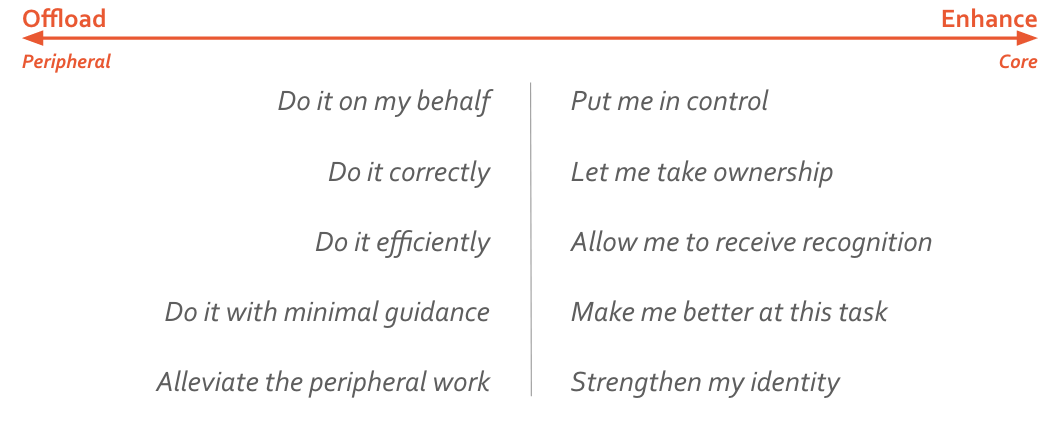

Design principles for assistance

The above can be summarised in a simple set of design principles to inform how AI-driven assistance is ideally experienced by knowledge workers. As is outlined in the impact section below, this is one of the frameworks which is guiding product teams across GSuite. These fundamental distinctions in how assistance should be experienced has important implications for who ‘owns’ different forms of AI and how it should be implemented within organisations.

Figure 8. Assistance design principles. (© Google, used with permission.)

Two types of AI

The paradox of peripheral work is that while it is perceived to be of lower value, trust in the assistance is more critical because workers are delegating work that is still regarded as their responsibility. For example, you may want to delegate filing your expenses, but if a false claim is made on your behalf then that puts your reputation at risk. Therefore trust in AI acting on your behalf must be exceptionally high. Trust is established when an assistant completes a task satisfactorily on a repeat basis. In these circumstances oversight is gradually withdrawn.

Therefore workers liked the idea of offloading both agency and ownership for peripheral work. On the other hand, they wanted to experience any assistance with core work as integrated and indistinguishable from their own efforts. They wanted to maintain and sometimes deepen agency and ownership of these tasks.

In practical terms this meant they liked the idea of their employer organisation as being the agent of peripheral work, while they personally retain control of their core work.

Figure 9. Preference for ownership differs based on type of assistance. (© Google, used with permission.)

Peripheral work = ‘Company AI’

Workers liked the idea of delegating peripheral work to a company-owned tool, meaning the company is responsible for positive and negative outputs rather than the worker. By extension, workers were open to the organisational AI being represented anthropomorphically as an external agent (like Google Assistant, Siri, Alexa etc).

This would be a resource that would be part of organisational infrastructure, and therefore remain in place if a worker were to leave the organisation.

Core work = ‘My AI’

In contrast because workers viewed core work as integral to their value and identity, they preferred the idea of a personal AI that would move with them between organisations. As they invested time training the AI it would become increasingly personalised and indistinguishable from their own capabilities.

In this sense ‘My AI’ should not be experienced as an external anthropomorphic agent but as largely embedded in their workflows and practices, to the point where it is not recognised to be AI as such and indistinguishable from their own capabilities.

The idea of ‘My AI’ can be seen to run counter to the trend of work becoming more collaborative – in this sense a ‘Our AI’ may seem like a better reflection of the way that work is developing. But this runs counter to the aspirations of ownership, autonomy and agency that emerged strongly from the research. As work becomes more complex AI may actually become a tool for maintaining personal agency and autonomy as it helps individuals automatically define and track their specific contributions within the context of the whole.

IMPLICATIONS AND IMPACT

For Google

The two concrete contributions the work has had for Google can be summarized as:

- Embedding a new set of taxonomies and frameworks that inform AI-related decision making throughout the GSuite organizationThe frameworks outlined in this case study have been socialised across both the executive and product layers of the organisation, helping teams prioritise and develop strategies. Previous to this work GSuite had many successful products that provided AI-driven assistance for knowledge workers, but lacked a foundational framework with which to categorise and evaluate existing products from a user perspective, nor a clear means for understanding where to innovate in the future. Our work has provided GSuite management with a set of adaptable tools to organise and manage innovation across product teams.

Figure 10. Amy Lokey, VP, User Experience, GSuite, introduces our foundational Core / Peripheral work framework at Qualtrics conference. (Lokey, 2018a)

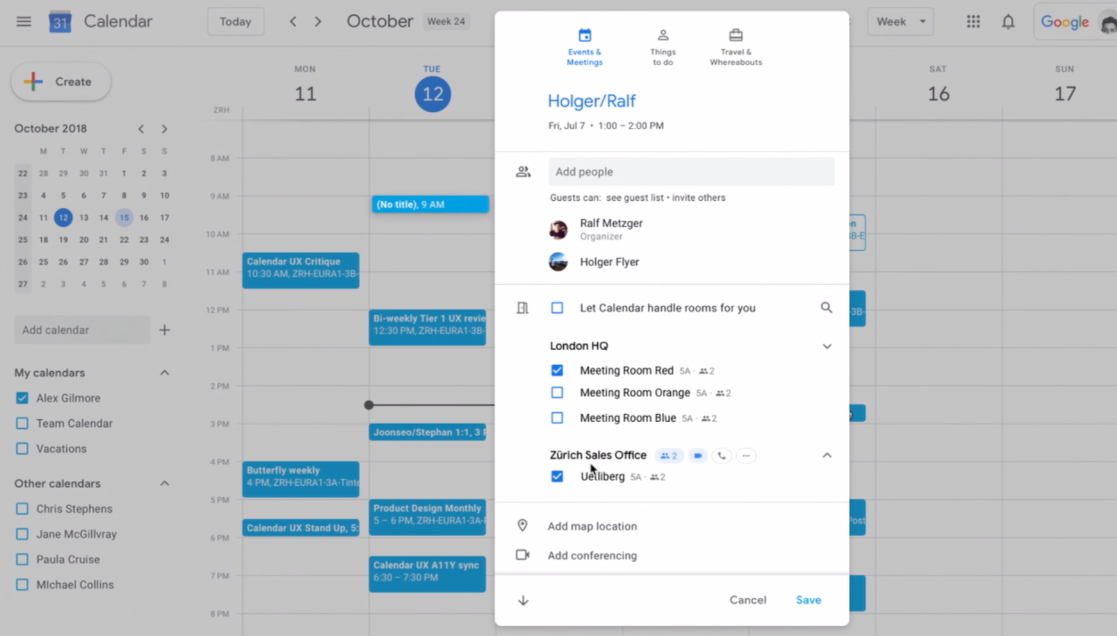

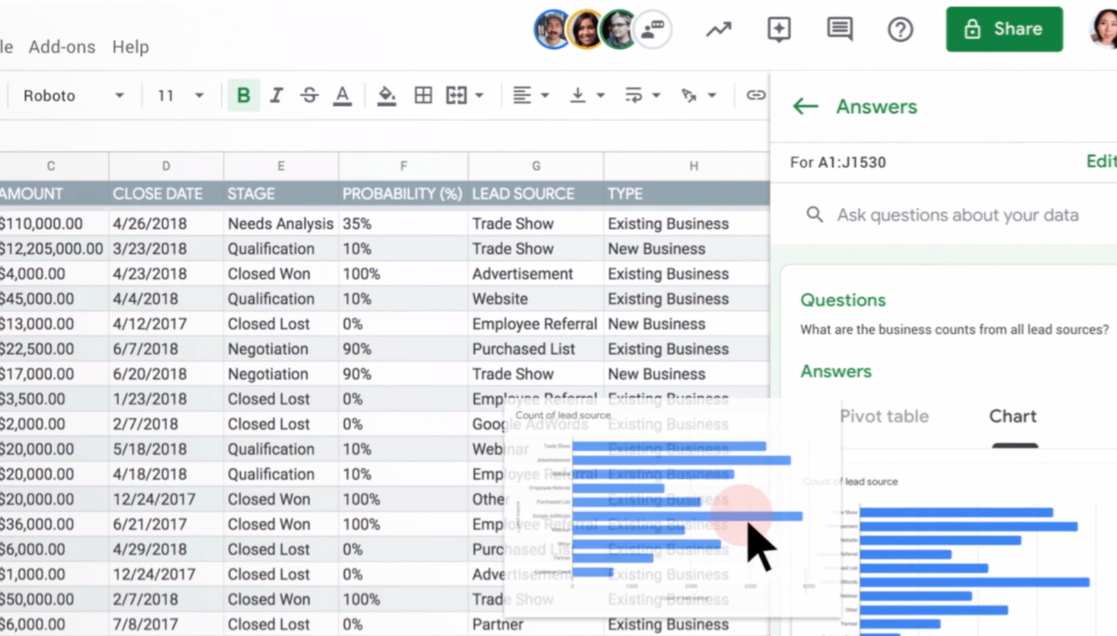

- Driving product innovation within specific GSuite teamsEach product team at GSuite (Gmail, Calendar, Sheets, Docs) is now using these frameworks to inspire and guide how they integrate AI into their products, with many examples already live

Figure 11. Calendar’s new auto Meeting Room allocator is driven from the idea of reducing Peripheral Work. (© Google, used with permission.)

Figure 12. Sheets new ‘Explorer’ feature enables users to generate charts using ‘conversational’ queries, augmenting ‘Core Work’. (© Google, used with permission.)

It’s also important to emphasise the ethical dimension here. By highlighting a worker-first perspective of what good ‘Assistance’ is at work, our project has guided Google towards sensitive solutions which help workers excel at their job, by both augmenting their skills and removing aspects of their work that were blocking them from excelling.

Our guidance would have looked different if we’d taken an IT-first perspective. As part of the project we conducted a number of management interviews with IT decision makers and it was clear their priorities were often quite different to individual workers. Their concerns primarily revolved around value for money, and seeing AI as a means to reduce costs – although there was evidence of the increasing role of worker preference in driving decision making (companies like Google and Slack have made influencing workers first central to their ‘bottom-up’ adoption strategies). This is not to underplay the importance of this perspective, but to emphasise the role of this project was to focus on the needs and priorities of the end user.

Public references to our work (see full reference in citations)

- Qualtrics conference keynote, 2018 (Lokey, 2018a)

- Keynote at Google NEXT conference (Lokey, 2018b)

- Interview with Teryn O’Brien for Silicon Angle (O’Brien, 2018)

For Knowledge Work

By the end of 2018 over 5 million businesses are paying to use GSuite worldwide (https://9to5google.com/2019/02/04/g-suite-5-million-businesses/). The influence GSuite has over the way people do work is enormous (especially if we include the consumer side of Gmail, then the number increases to 1.4 bn users.)

By helping workers to focus on Core Work and reduce Peripheral Work, GSuite will contribute to the streamlining and specialization of roles as they are optimised towards leveraging the specific skills and aspirations of the individual. From this perspective Knowledge Work should also become more rewarding and enjoyable as users focus on work that they find most interesting and valuable.

However, for this vision of knowledge work to be realised there are a couple of questions that warrant further exploration:

How do we enhance Core work in a collaborative environment?

Work is simultaneously becoming more complex and more collaborative. Given each worker has a personal incentive to focus on Core Work this may lead to tensions as work overlaps and workers compete to do the same high-value work. And more importantly, given that Knowledge Work requires increasingly complex forms of collaboration, it may become more difficult to define and quantify unique contributions and, by extension, the nature of “your core work” vs “my core work”.

One outcome may be that role definitions becoming increasingly collective and integrated, so that Core Work is not defined in such individualistic terms. Alternatively AI may actually help workers parse, define and measure their contributions in this more complex environment. This is an area that we would like to explore further.

How will the removal of Peripheral work affect Core work?

Just like other workers, it is easy for ethnographers to segregate the work we do between ‘Core’ and ‘Peripheral’. For example, we may want to minimise the logistical burden inherent in conducting global fieldwork. From organising transportation to syncing meetings across time zones there are many tasks that seem to detract from time spent on what we commonly think of as our core work (namely field research, pattern recognition, meeting with clients).

However, there is a danger in minimising work that is perceived to be Peripheral. Last year at EPIC we outlined the danger of ‘AirSpace’ – the idea that global platforms like Google, Uber and Airbnb are making ethnography ‘frictionless’ and thereby reducing its richly textured scope to an extended interview (Hoy, 2018). To put it simply, sometimes getting stuck on public transport may feel like Peripheral Work, but it can also lead to the most unanticipated, abductive insights. In this sense, the work we perceive to be Peripheral may be reframed as Core.

In this sense removing the rough edges of Knowledge Work may not always be a good thing if it restricts our idea of what our work is, or could be. And this may be a challenge that extends to other Knowledge Workers too. This is another area we would like to dig deeper into.

For Ethnographers

There are some important learnings from this project on how we study AI as ethnographers. In the context of work, we found framing ‘assistance’ in human rather than technological terms was an important way for us to begin our conversations with participants. This enabled us to put pre-existing ideas about AI (from media narratives about jobs being automated to consumer instantiations such as Siri or Google Assistant) to one side and focus on the everyday support they would appreciate at work. It was only once we established these ground rules that we introduced the idea of technology.

Secondly, performing ethnography with multiple workers in the same team enabled us to better understand the distinctions and tensions between individual autonomy and teamwork, and how one person’s Core work can be another person’s Peripheral work. Also, we could triangulate between the claims of different workers and observe team dynamics, enabling us to build up a truer picture of everyday work.

REFERENCES CITED

Cross, R, Taylor, S, and Zehner, D, July-Aug 2018, “Collaboration Without Burnout”, in Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Davenport, T.H. and Prusak, 1998, Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Davenport, T, 2005, Thinking for a Living: How to Get Better Performances And Results from Knowledge Workers, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Davis, J, et al., 2018, “The Future of Work” in Vanguard Megatrends, Accessed October 28th, 2019 https://pressroom.vanguard.com/nonindexed/Vanguard-Research-Megatrends-Series-Future-of-Work-October2018v2.pdf

Garimella, K, 2018, “Job Loss From AI? There’s More To Fear!”, in Forbes, Accessed October 28th, 2019 https://www.forbes.com/sites/cognitiveworld/2018/08/07/job-loss-from-ai-theres-more-to-fear/#359b388b23eb

Hoy, T, 2018. “Doing Ethnography in AirSpace: The Promise and Danger of ‘Frictionless’ Global Research.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings

Lokey, A, 2018a. “Making Magic from the Mundane.” Keynote Presentation at Qualtrics Conference Accessed October 28th, 2019 https://www.qualtrics.com/events/x4-px-breakthrough-sessions/making-magic-from-the-mundane/?

Lokey, A, 2018b. “Product Innovation Keynote.” Keynote Presentation at Google NEXT Conference Accessed October 28th, 2019 https://youtu.be/PZ1Lqxfs1yw?t=3796

O’Brien, T, 2018. “G Suite UX exec becomes ‘chief empathizer’ to fully engage users.” Interview with Silicon Angle, Accessed October 28th, 2019 https://youtu.be/PZ1Lqxfs1yw?t=3796