During the postpartum period, significant clinical and social supports exist for the care and wellness of a newborn baby. Yet over the same six weeks, new moms report feeling abandoned and alone. In this case study, we share the research methods we used to evaluate an early prototype of a digital tool designed to offer support and healing guidance to postpartum moms. We discuss our strategies for onboarding participants during this period of significant transition, and for engaging them for six weeks through a novel study design. This work highlights the deep friction new moms often face navigating their own physical healing while so much attention and care—theirs and others’—is focused on the baby. It also offers an approach to reducing an ongoing friction in new product development: what people say they want may differ significantly from what they actually want or need in real-life contexts.

Key words: maternal mortality, postpartum support, femtech, experience prototype, research design

INTRODUCTION

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the U.S. maternal mortality rate places us last among high-income countries. Our overall rate of 24 deaths per 100,000 women is nearly twice as high as the next country on the list, and three times higher than the mortality rate of most other high-income countries (Gunja, Gumas, and Williams 2022). In the U.S., 40% of all maternal deaths occur in the early postpartum period (from one day to six weeks after delivery) (Tikkanen et al. 2020), and Black and Native women are two to four times as likely to die as white women (CDC 2023).

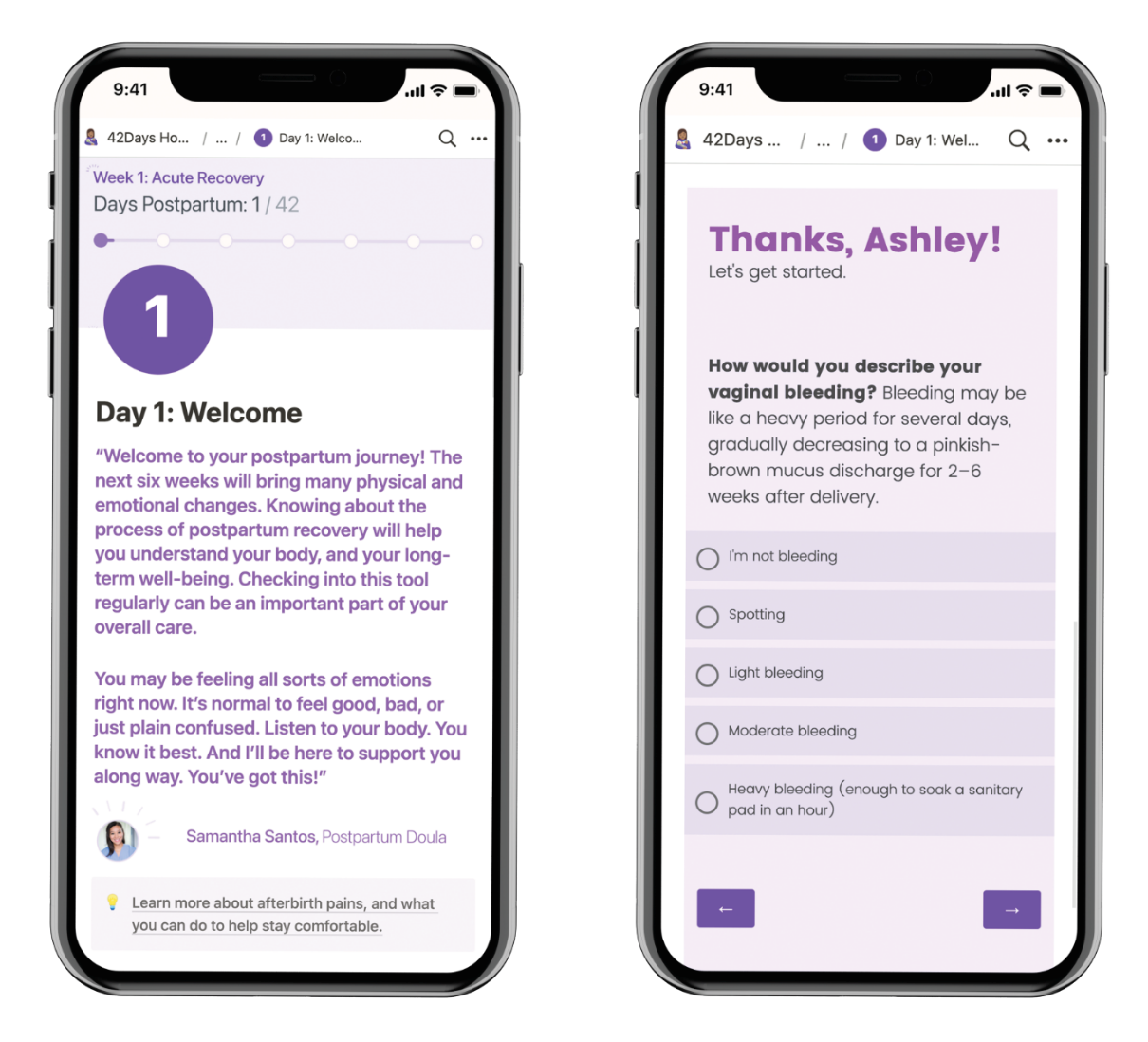

A clinical research team at the University of Pittsburgh saw the potential for a digital tool to help address the maternal mortality crisis in the U.S. Through a person-centered and stakeholder-engaged process, they conceived of a mobile application that would help new moms carefully monitor their healing and recovery. This app would provide clinical information about a normal healing trajectory and when to seek medical care. They developed an early Figma prototype to articulate key features of the tool, but were left with many questions about how it might actually fit into the lives of new moms during the postpartum period. In 2021, the clinical research team (led by one of the authors) launched a collaboration with Dezudio, a small design consultancy (led by the other authors), to evaluate the prototype and to determine what updates might be necessary to help it better fit into the lives of postpartum moms—before building a functional version of the app.

This case study describes our interdisciplinary design research collaboration and the frictions that were identified in the process. First, we provide some context about the maternal mortality crisis in the U.S. and the gaps this tool is intended to fill. Second, we share the methodology we used to gather formative design input from moms who had recently given birth, and to evaluate an early “experience prototype”—a lightweight version of the tool built using off-the-shelf technologies—that we sent home with new moms as they left the hospital.

Finally, we will provide our key takeaways, focusing on frictions we encountered in this work. A clear picture emerged of a deep friction new moms often face in navigating their own physical healing while so much attention and care—theirs and others’—is focused on the baby. This friction is experienced at personal, social, and clinical levels; the moms we spoke with recognized their tendencies to forget about themselves and their own needs, the behavior of friends and family members who only ask after the baby, and the sharp contrast between the medical attention they received before delivery and after. Understanding the forces that contribute to this situation has proven essential in shaping the design of the tool and the tone of the information it provides.

The other friction we observed is common in new product development: what people say they want may differ significantly from what they actually want or need in “real life” contexts. But how can we create opportunities for meaningful evaluation of something that does not yet exist? Our approach to this research enabled us to conduct interviews that were grounded in lived experience—not based on speculation or conjecture about likely preferences based on a brief introduction to the concept in isolation from its true context.

We hope this case study sheds light on the frictions postpartum moms face and brings their experience to the forefront as our society continues to work to combat the maternal mortality crisis. We also hope to reduce an ongoing friction in new product development by sharing three principles that can help bring new innovations to life that are better aligned with the true needs and goals of the audiences they are intended to serve.

CONTEXT

In response to the overwhelming maternal mortality crisis in the U.S., researchers at the University of Pittsburgh developed a concept for a mobile app that would provide new moms with timely information relevant to their own healing in the first six weeks of the postpartum period. A key feature was a symptom tracker that would help new moms self-triage their symptoms, including those which may be routinely misidentified as non-critical (e.g., severe headaches). Customized results from each day’s tracker would emphasize the importance of taking action on symptoms or situations that are cause for concern, and offer reassurance when self-reports indicated a “normal” healing trajectory.

To develop this concept, the research team took a person-centered approach, grounded in frameworks of health equity. The process involved engaging with stakeholders, including those who had experienced the postpartum period, throughout the conceptualization and early design process. The team also incorporated evidence-based best practices to address identified gaps in knowledge, preferences, and practice related to postpartum care and healing (Krishnamurti et al. 2022, Krishnamurti, Simhan, Borrero 2020).

During the initial design phase, the research team enlisted support to prototype a digital tool in Figma that would illustrate key screens and features. While the features and content for the app emerged from extensive stakeholder engagement and evidence-based best practices, the clinical team was left with unanswered questions about the tone, delivery, and timing of the content. More generally, they remained unsure about how this new tool might fit into the cadence of the lives of new moms during a time of potentially overwhelming adjustments and significant healing.

Before investing to build a fully functioning version of the app, the team sought to develop a more robust picture of the lived experience during this crucial period to help the tool fit as seamlessly as possible, and to maximize its utility and uptake. They also wanted to evaluate the content delivery and planned cadence to see how well it matched the need for information in this time period, and to determine what adjustments might be necessary. Finally, the team needed to achieve these research goals without adding extra burden or intruding on a time in a new mom’s life that can be overwhelming, joyful, and frightening all at once. The data collection described below was approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board (#s 21070134; 22020017).

With the aforementioned objectives in mind, the clinical team partnered with Dezudio to develop a plan for conducting additional research. In early brainstorming sessions, we articulated a long list of driving questions. Would new moms find value in receiving a daily “drip” of information, or would they be overwhelmed by it? Was the right content being offered at a time when it would be useful? Would they appreciate the sole focus on mom’s healing, or would they want information about the baby in order to gain real value or to remain committed to using the tool? How often would new moms want to—or be able to—find the time to use the app? How and why would they engage with the symptom tracker, and would they find that feature useful for understanding what was “normal” or cause for concern?

The clinical team originally imagined that information in the tool would be served in small topics day by day, but they didn’t feel fully confident that this mode of delivery would be preferable to a fully accessible resource library or set of reference articles. They were also uncertain about the kinds of topics that would be most useful to new moms at each stage of the postpartum journey, and were curious whether the tool should include content about babies (feeding, sleep, development, etc.) or if that information would detract from the focus on moms’ healing. Answers to these and other questions would inform the next iteration of the app, allowing the team to make necessary adjustments before investing more heavily in the development and dissemination phases.

METHODOLOGY

Our research initiative included two phases. First, we conducted interviews with new moms, and invited them to complete a card sort activity. Then, we recruited moms who had just given birth to participate in a six-week “experience prototype” evaluation, combined with an at-home video diary study. We describe each phase in detail below.

Interviews and Card Sort: Getting Immersed and Gathering Early Input

The initial phase of research helped the Dezudio team get immersed in the postpartum space, and allowed us to investigate a few key questions to inform how we built the experience prototype that would be used in the subsequent phase. We conducted eight interviews and topic card sorts with new moms who were just past the acute postpartum period, ranging from six to eight weeks postpartum. In these interviews, we asked participants what information they were searching for and when, and which digital tools they were already using to seek it out. In the card sort exercise, new moms reviewed a broad collection of possible informational topics relevant to the postpartum period. Then they sorted and prioritized these topics—and suggested new ones—based on what was most important to them. Finally, we brainstormed together about possibilities for how a digital tool might have supported them through their postpartum experience. We introduced the existing concept prototype to discuss what they liked and what might be improved.

Outcomes from these interviews directly informed the prototype we created for the subsequent phase of research, where we aimed to provide participants with the experience of having access to the information and key features from the tool. (For example, rather than choosing between a single topic each day or a comprehensive library of information, we built the prototype to accommodate both modes.) We also used the context and insights we gained from the interviews to plan the details of the next phase—where new moms would have access to an experience prototype from the first day of their postpartum period.

Experience Prototype and Diary Study: Evaluating the Approach

For the second phase of research, we wanted participants to experience having access to the tool’s content and symptom tracker in real-time, as they navigated their physical recovery in those early weeks at home with a new baby. Nine new moms who enrolled in the study accessed the prototype for six weeks. They participated in interviews at the midpoint and at the end of the study period. At each interview, we discussed participants’ perceptions of the tool’s utility, as well as any motivations for using it. We also sought to better understand how this app did and did not integrate with their lived realities in the postpartum experience. We evaluated the tool’s content and structure, and whether the scenarios of use in which we hypothesized it might provide value were correct—or if we needed to adjust features and functionality to help it better meet real-world needs.

In researching off-the-shelf tools we could use to simulate how the app was intended to work, we learned quickly that we would be best served by relying on an ecosystem of services carefully orchestrated to work together. We used Notion, a “wysiwyg” hyperlinked document builder, to create content pages in the app for each daily topic, and for more detailed articles. Building an information-heavy experience prototype required us to create all the content the tool would ultimately deliver, a task that is often left to later in the development process. We also needed to consider the tone and reading level. To be inclusive and accessible to all potential users of the tool, the articles and other informational pieces were written with the target of a sixth-grade reading level.

We built the daily symptom tracker using the survey tool Qualtrics, and were able to embed questions directly on each day’s topic page in Notion. We built out the logic so participants would receive realistic results and recommendations based on the responses they entered. We also embedded short surveys asking them to rate the usefulness of each day’s content, and prompting them for other additional topics they were curious about on any given day. To simulate notifications, we used SlickText, an SMS marketing service, to send each participant daily text messages that linked through to each day’s topic in the prototype. The link shared with each participant for each day was unique, and for the duration of the study, we used Linkly—a URL shortener and link tracking service—to monitor whether and how often participants clicked from their text messages to the prototype tool.

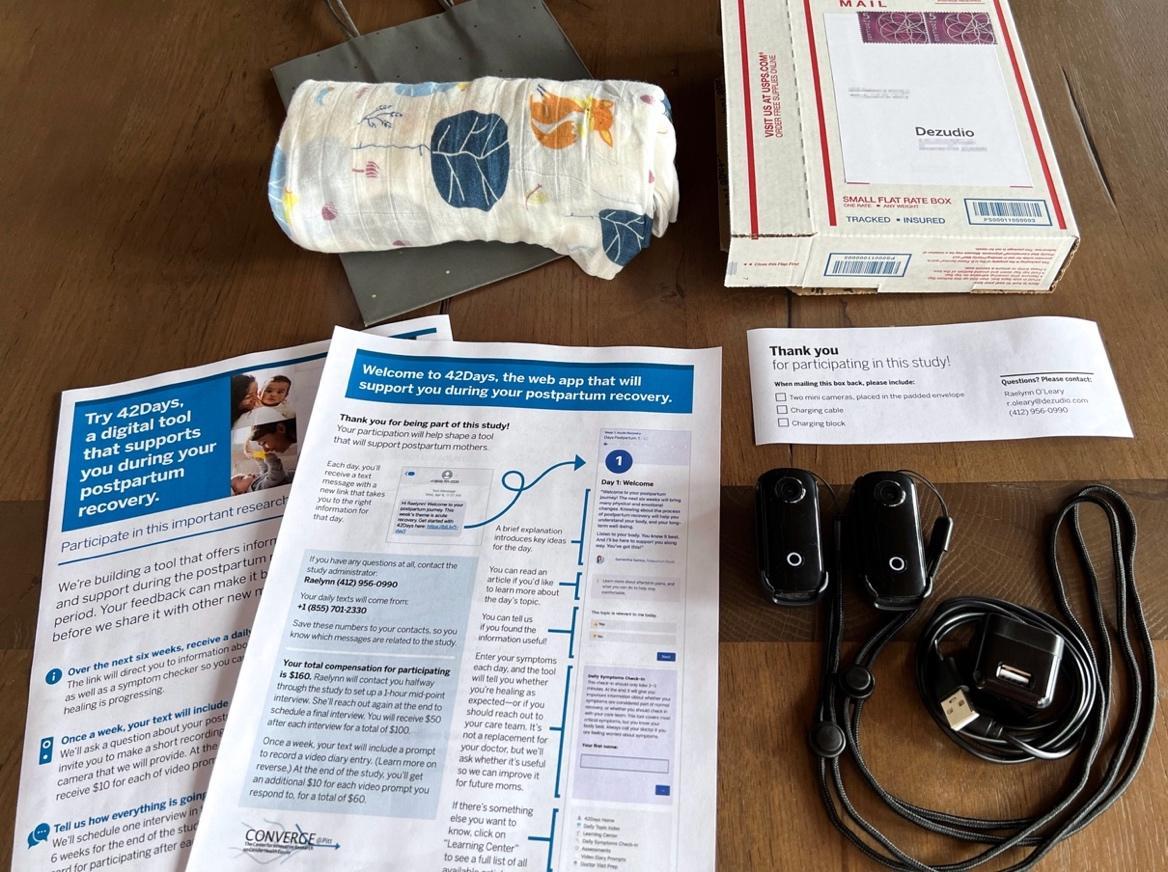

To give us a richer view of the time between interviews, we offered an optional video diary portion of the study. Once a week over the duration of the six weeks, the day’s text message was a diary prompt asking participants to reflect on a particular topic related to their experience and how they used the app during this time. We provided two lightweight, portable video cameras for recording responses to diary prompts. (The cameras had no internal playback or editing capability, which encouraged participants to record entries “off-the-cuff” by limiting opportunities for self-scrutiny or the need to review, edit, or re-record.) Participants received a small amount of additional compensation for weeks where they made diary study entries.

Over the course of four days, we recruited 15 new moms on the postpartum floor to participate in the experience prototype and diary study. Participants agreed to receive a daily text message and speak to us twice in interviews. They were compensated for each of their two Zoom interviews, but no incentive was tied to whether or not they actually interacted with the prototype. This approach allowed us to speak with them about how and when it was feasible and valuable for them to use the tool (or not), and why. Additional compensation was provided for each diary study prompt for which they recorded video.

Due to their disproportionate risk in the postpartum period, we prioritized recruiting people of color and beneficiaries of Medicaid insurance. We also sought participation from those who had different delivery methods (vaginal, planned C-section, unplanned C-section) or had experienced complications such as gestational diabetes, hypertension, pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, and having a baby in the NICU. The participants we recruited were White non-Hispanic (n=8), Black non-Hispanic (n=2), Multiracial Hispanic (n=2), Black Hispanic (n=1), White MENA (n=1), Asian (n=1). Of those recruited, eleven ultimately interacted with the prototype and nine participated for the full six weeks. (The other two were unavailable for both midpoint and endpoint interviews, thereby not meeting the participation requirements for qualitative data sharing.) Our final breakdown was White non-Hispanic (n=6), Black non-Hispanic (n=1), White MENA (n=1), Asian (n=1).

KEY INSIGHTS

Through these two phases of research, we identified and prioritized tactical updates to improve the structure of the app and its content. For example, participants wanted topics that were more tailored to their specific situation (like whether they had a vaginal delivery or C-section, or had a baby in the NICU), and suggested additional topics based on their experience. Another example was related to symptom tracker usage. Participants used it heavily in the first two weeks, but then tapered as they built a solid understanding of key risk factors. This pattern led us to consider how the app might promote the symptom tracker early on, but let it fade into the background as healing progresses and information needs change.

We identified opportunities for many additional tactical updates, but the broader significance of this work lies in the two fundamental frictions we describe below. We hope that what we learned may help others to understand and center the lived experience of new moms in the development of technology and tools that are built for them. We also hope our approach to research and the principles we share will help other researchers find ways evaluate their ideas early and in the context of a lived experience—even when it seems challenging to access participants.

1. Understanding a key area of friction of the early postpartum experience can fundamentally shape how we design tools that support new moms.

After delivery, birthing parents experience a fundamental friction between a critical need for self care in a context where their attention (and the attention of people around them) has largely shifted to the new baby. Across interviews and video diary studies with our 17 participants, a clear and consistent narrative emerged about their experiences in the weeks preceding and shortly after delivery.

New moms reported experiencing a dramatic shift in attention and care—both internally and externally—between the weeks leading up to delivery and their early weeks at home once they leave the hospital. In the last weeks of pregnancy, birthing parents attend frequent medical appointments to monitor their health and the progress of the pregnancy. Special circumstances or concerns are monitored carefully, and patients receive specific instructions about what might be cause for concern. Friends, partners, and relatives check-in frequently on how expectant moms are feeling. Once the baby comes, moms’ attention veers radically from their own pregnant bodies to this new and seemingly fragile life that exists outside of them. Friends’ inquiries also shift from concerns about the mom’s wellbeing to how the baby is settling in.

The switch from pregnancy to delivery to the first few days and weeks home is a sharp and jarring contrast for new moms—often leaving them feeling in the dark and abandoned to figure things out on their own. During the postpartum period, significant clinical and social support exists for the care and wellness of a newborn baby. Yet over the same six weeks—and despite a whirlwind of information provided in the hospital at delivery—many new moms we spoke with reported feeling anxious, abandoned, and alone.

“I have more questions about her rather than me because I kind of put myself on the side.”

(N-S2)

“…We don’t stop and think until, like two months past. What about me? Maybe three months on to three months past? Well, that’s what happened to me. You just want to focus on the baby and whatever is around you. I forgot about myself at all. Totally.”

(R-S1)

“First time around I didn’t have any support in terms of information. You leave the hospital and it’s terrifying. You have the pediatrician for support for the child but I didn’t know how to care for myself.”

(V-S2)

“I just wasn’t informed about how long and what to look out for symptom-wise. When I had an ectopic pregnancy, they rattled off the symptoms to look out for every visit. I didn’t get that after delivery.”

(V-S2)

For many, the hazy and often uncertain postpartum period ultimately becomes a time of salient learning and significant evolution. But for some, the lack of focus and education on their healing—including what is considered normal, and what is cause for concern—becomes a critical risk factor that may impact health outcomes significantly. Experts identify “patients’ knowledge of warning signs” and “not recognizing when to seek care” as critical issues related to maternal mortality risk. (Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths, 2017. Report from maternal mortality review committees: a view into their critical role.)

The sensitivity we developed to this friction through meaningful, grounded engagement with new moms in the postpartum period will fundamentally inform our work moving forward on the tool. We had a firsthand view of the essential role that a digital tool can play in providing critical information and helping new moms pay attention to and prioritize their own care. Moving forward, our design decisions are informed by a clear view of the inherent friction new moms face in caring for a new baby and themselves.

2. Evaluating an “experience prototype”—a version of a proposed tool or service accessed in its true context—early in the design process can help reduce a significant ongoing friction in new product development.

Prototyping an experience is challenging, but yields significant practical value in reducing a longstanding friction in new product development: How can users respond or react to a new product that does not yet exist in the world? And how can we mitigate the gap between users’ anticipated preferences, and their real preferences once they have access to something new? This friction can be reduced by applying three important principles for conducting early design research.

Make a Prototype That Reflects the Essential Experience, and That People Can Engage With in Their Real Lived Circumstances.

Our approach to this research relied on the use of an “experience prototype,” which Marion Buchenau and Jane Fulton Suri of IDEO described as “methods and techniques which support active participation to provide a relevant subjective experience” (Buchenau and Suri 2000, 425). Given the nature and complexity of this time in peoples’ lives, we knew it would be unlikely that they could accurately anticipate what they might want or how they might feel during that timeframe. We were committed to finding a way to let them have that subjective experience using a simulated version of this tool, so they could react to and analyze what it was like in the moment.

The value of engaging with new moms in context was demonstrated by a key difference between what we heard in interviews from new moms who had not experienced a version of the tool during the postpartum period, and from moms interacting with the prototype during the six weeks after delivery. In the interviews, our participants were excited about the possibility of a tool that would be focused purely on their needs—even to the exclusion of information related to the baby. When asked explicitly whether a tool with baby content might provide more value, participants emphasized the availability of tools and resources devoted to the care and needs of a new infant, and the dearth of information for moms in the postpartum period.

[Interviewer] “You might have noticed that there’s no information about babies in the tool—that it’s all about just you as mom. Do you have any thoughts about that?” [Participant] “I think it’s great. Like, I mean, it’s hard not to notice, you know, the difference in the hospital and beyond of like, just the amount of attention the baby requires versus like the mom. It’s like, ‘Are you dying? No? Good. Let’s go.’”

(H-S1)

“I would love to have an app that’s just focused on me. ’Cause I’m not getting it anywhere else.”

(K-S1)

However, when given the chance to interact with a comprehensive prototype in the midst of managing their new babies’ care, participants expressed a clear preference for including information related to the baby. They reported that their wellbeing and that of the baby were inextricably linked; supporting them in caring for their new infant was essential to helping them feel fully supported.

“I remember doing the app in the first couple days. There was a question about is there anything else you’re interested in. I kept putting in whatever the problem was with the baby—how to deal with overtired baby, how to deal with gassy baby. … I think that it is a good thing that has an app that is just focused on mom. I know I just contradicted myself. But having nuggets about baby could be helpful for mom’s mental health.”

(E-S2)

“A little more baby information would make it more of a ‘go to.’”

(K-S2)

In this process, we first identified and prioritized what aspects of our proposed experience were most essential. Then we sought efficient and affordable ways to represent those key elements to our audience, and spoke with them about the subjective experiences our prototype was able to provide. In our case, they symptom tracker and the information in the tool—promoted through a daily cadence of topics and notifications—were critical, so we found ways to represent those features by cobbling together a prototype using off-the-shelf tools that was good enough to give our participants a view of what their experience might be like if an app like this was fully built.

When Recruiting Participants in Complex Situations, Find Creative Ways to Meet People Where They Are.

Recruiting moms to participate in the experience prototype and diary study during the postpartum period was a daunting task. We were initially concerned whether we would find people who were willing and motivated to participate. We considered recruiting through birthing networks and online forums, but were uncertain about recruiting pregnant women who might drop out with the flurry of activity once the baby arrived. In the early phases of defining the study, we shared our plans and target participants with clinicians and other patient care practitioners at our affiliated women’s hospital, and gathered their input on possible strategies for recruitment. Fellow researchers, hospital clinicians, and doulas offered feedback on materials, study requirements, and participant incentives—and encouraged us to recruit in the hospital after delivery rather than seeking participants before delivery.

We enlisted a student from the University of Pittsburgh who was also trained as a doula to conduct recruitment. She had credentials that allowed her to be on the postpartum floor and was able to easily establish relationships with the nurses working there in the days leading up to our recruitment window, letting them know when she would be circulating on subsequent days and making sure they understood her goals and the aims of the study.

On recruiting days, the recruiter was able to enter the rooms of new moms on the postpartum floor, checking in on them and talking with them about their birthing experience. She introduced the opportunity to participate in the study using a one-page flier that clearly outlined the process and articulated requirements for participation. She outlined the information that would be provided in the tool, and what they could expect to learn from it. Ultimately, she was able to paint a picture to potential participants not only of the value their participation would bring to developing something to support new moms like themselves, but also how they would gain valuable and timely information by participating, which was a likely motivator.

By engaging early and often with stakeholders and hospital staff, we built relationships and leveraged their expertise to develop a successful recruiting strategy. We were able to gain access to participants in the place where they naturally gathered. We enlisted the support of an expert liaison who could connect with prospective participants in a meaningful way, and clearly explain the involvement required and possible benefits of participation. These factors helped us successfully attract participants, and will inform our recruiting strategies moving forward in similarly challenging recruiting scenarios.

Make the Requirements for Participation as Simple as Possible, Clearly Communicate Requests to Potential Participants, and Stay Out of the Way.

Because our research involved participants at a complex and sensitive time, we pushed ourselves to prioritize research goals carefully and to make our requests as simple as possible. We set out to answer our most critical questions in ways that would allow participants to engage authentically without feeling pressure to interact with the tool or behave in a certain way due to their study participation.

Our streamlined set of criteria for participating included only two requirements: receiving daily text messages promoting a link to the day’s topic in the app prototype, and participating in two interviews (once at the midpoint around four weeks, and once at the end after week six). Internally, we wrestled with issues of scope creep and continually pared back both in terms of process and in the information prototype we gave participants access to during the study.

We made video diary entries optional to simplify the study requirements, but offered additional compensation for those who chose to complete them ($10 per video diary entry). There was no requirement that the participant ever interact with the prototype, or click through on the links they received by text message. When we interviewed participants who only engaged with the prototype a little or not at all, we were able to gather valuable information about why the app was not fitting into their lives during this time.

Our team sees preparing assets and materials for those that will participate in design research as a communication and experience design exercise. The team put together a “study kit” for potential participants that included an instruction sheet, two cameras, and a baby blanket to be sent home with new moms from the hospital.

Because we had the goal of engaging with study participants for a relatively long period of time—over the course of six weeks—we felt that connecting with real members of the study team for recruiting, onboarding, and throughout would work better than using an online recruiting service and/or a digital research platform. Upon enrollment, participants were given contact information for the study liaison, and could expect to be contacted with study notifications (an initial welcome text went out to participants as soon as they were enrolled). The expectation was also set that participants could contact the study liaison via text or phone at any time over the course of their six-week participation. When it came time for each of the participants’ two interviews, they received a text with a link to easily choose an hour time slot that worked well for them. Staying connected with participants but out of the way allowed us to build rapport and trust, while balancing the provision of a framework for genuine and authentic interactions throughout the postpartum period.

CONCLUSION

Engaging with new moms in depth by giving them the chance to experience and reflect on key aspects of using the app in the postpartum context allowed us to build a robust understanding of our participants and their needs. We learned details about how they might engage with the tool, and what they found valuable, that would not have been evident—to them, or to us—had we only interviewed them or described our ideas to them for feedback. For our team, this initiative underscored the importance of finding a way to make a version of what we might propose, and giving people the opportunity to use it in the most realistic and authentic circumstances possible. Even when the context or audience might present challenges, there are strategies for study design and for designing the participant experience that can help people be willing and motivated to remain involved. In this research initiative, prototyping the experience prior to fully committing to the concept enabled our interdisciplinary team of clinicians, designers, developers—and new moms who will remain engaged as part of a stakeholder team—to proceed with confidence as they continue the work of bringing the idea to fruition.

Even in circumstances where access to users feels limited or the topic area is high-stakes—like in the first six weeks after giving birth—we can lean on design research and experience prototyping to ensure that tools we build are aligned to the needs of the people they are intended to serve. New moms in the postpartum period are a population who can and should benefit from the design of tools and services that take this approach.

For many new moms in the U.S., navigating the postpartum period is a dance of caring for a new life while healing and recovering, with little information or support for yourself. We see potential for better digital tools to help combat our growing maternal mortality crisis. The outcomes of this research are currently being applied to the design and development of a postpartum support app, with plans for distribution broadly to new moms through state public health channels. This population needs designers and design researchers to understand their situation deeply and authentically, and to build tools that can help them navigate the friction they face.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Raelynn O’Leary is Partner and Co-founder of Dezudio, a women-owned design firm in Pittsburgh. Her practice is focused on research and design for decision making and support tools and communications, largely in the realm of women’s reproductive health. Raelynn is Special Faculty in the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University.

Ashley Deal is a Partner at Dezudio, and Special Faculty in the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University. In her 23-year career as an information and interaction designer, Ashley has aimed to facilitate access to important information that people rely on to make critical decisions, and to help people understand each other.

Tamar Krishnamurti, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. She works on issues at the intersection of health, risk, and technology, developing processes, (digital) tools, and communication strategies, grounded in psychological theory, to support informed decision making. Dr. Krishnamurti received the 2020 Kuno Award for Applied Science to develop mobile health strategies to address maternal morbidity and mortality risks.

NOTES

A special thank you to the team at Hand & Glove who built the initial 42Days concept prototype, and to the many clinicians who have been continual stakeholders and willing to lend their knowledge and expertise to this work. Thanks to Anna Abovyan for co-facilitating the initial round of user interviews and creating the symptom tracker surveys and associated logic for the prototype. Thank you to Alison Decker, study coordinator who navigated the IRB process and provided recruiting and project management support. Thanks to Megan Dahl for research support on content development and Meghana Vemulapalli, who showed expertise and care as a doula entering the rooms of new moms on the postpartum floor to connect, offer support, and enroll participants in our research. Special thanks to Hannah Koenig who, while working with Dezudio, not only managed this product and conducted and synthesized the first round of interviews, but also outlined the resourceful approach to creating a working prototype, and built out the full prototype in a way that allowed postpartum new moms experience the value of having a tool like this in their lived context.

Finally, our deepest thanks and recognition to the new moms who participated in interviews and diary studies and allowed us to see into their lives during this crucial time. Their willingness to share their experience will do much to help other new moms in the postpartum period and hopefully ultimately aid in the development of systems of support to tackle our maternal mortality crisis.

REFERENCES CITED

Gunja, Munira Z., Evan D. Gumas, and Reginald D. Williams II, “The U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis Continues to Worsen: An International Comparison,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, Dec. 1, 2022. https://doi.org/10.26099/8vem-fc65

Tikkanen, Roosa, Munira Z. Gunja, Molly FitzGerald, and Laurie C. Zephyrin, Maternal Mortality and Maternity Care in the United States Compared to 10 Other Developed Countries (Commonwealth Fund, Nov. 2020). https://doi.org/10.26099/411v-9255

Krishnamurti, Tamar, Mehret Birru Talabi, Lisa S. Callegari, Traci M. Kazmerski, and Sonya Borrero. A Framework for Femtech: Guiding Principles for Developing Digital Reproductive Health Tools in the United States. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2022; 24(4):e36338 https://www.jmir.org/2022/4/e36338

Buchenau, Marion and Jane Fulton Suri. (2000). Experience Prototyping. Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, DIS. 424-433. 10.1145/347642.347802.

Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. (2017). Report from maternal mortality review committees: a view into their critical role. Retrieved from https://www.cdcfoundation.org/sites/default/files/upload/pdf/MMRIAReport.pdf

Maternal Mortality: Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/discover/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system

Krishnamurti T, Simhan HN, Borrero S. Competing demands in postpartum care: a national survey of US providers’ priorities and practice. BMC Health Services Research. 2020 Dec; 20:1-0.