This case demonstrates how ongoing ethnographic research from within a corporation led to the re-segmentation of a market. The first part of the case focuses on how a team of social science researchers at a major technology company, Intel, drew on past research studies to develop a point-of-view on the increasing importance of content creation across a range of populations that challenged the findings of a quantitative market sizing study. Drawing on earlier qualitative work, the team was able to successfully argue for the value of ethnographic research to augment these findings and to show how research participants’ orientations toward technology constituted a more significant, and more actionable way of segmenting this new market than professional status, the differentiator used in the quantitative study. The second half of the case highlights the process of driving business change from within a large corporation. By turning an ethnographic eye on their own organization, drawing on past research, and by sharing unfinished results in workshops to grow the project in phases, the team was able to build stakeholder buy-in, and prime the organization for more ready adoption of ethnographic insights. As a result, the team’s findings led to a substantive change in Intel’s perspective on digital content creators, and to new products and marketing strategies. The team won a divisional award for defining a strategy that led to a profitable growth area for the corporation.

INTRODUCTION

This is a story about the value of cumulative ethnographic work from within an organization, the role of ethnography in shifting the perspective of internal corporate stakeholders, and driving impact with a new segmentation.

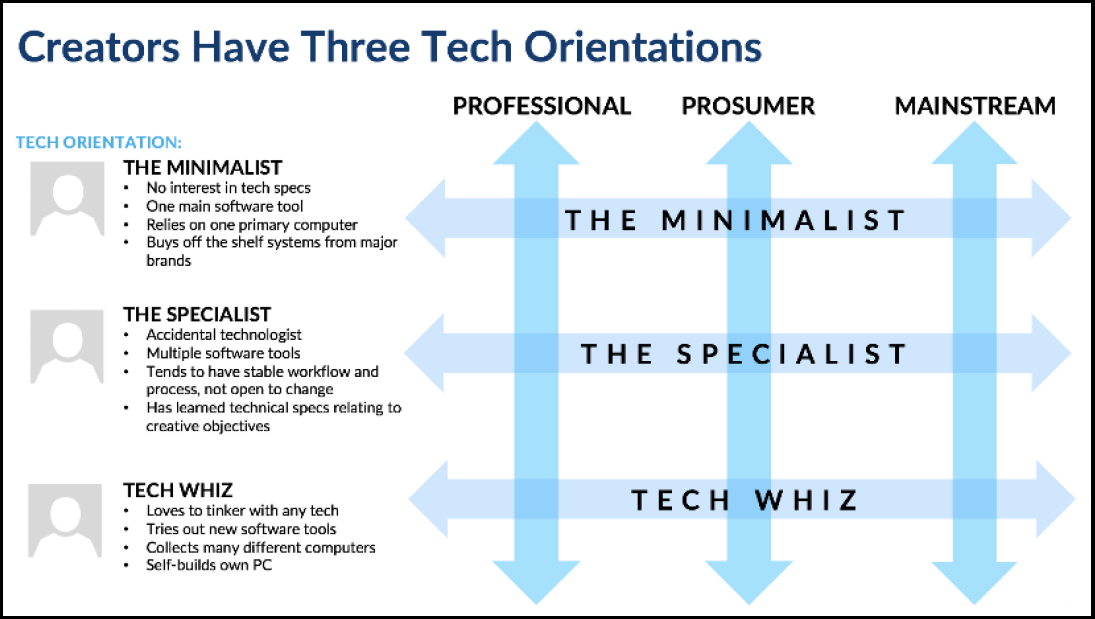

With increasingly powerful computers available at lower and lower prices, the shift in processing from client devices to cloud and data centers, and the gradual approach toward market saturation, Intel was increasingly concerned with declining sales in the desktop market. In an effort to shore up that business, Intel had been trying to identify new markets for whom high end computing mattered. Some members of the Desktop Business Unit saw a potential in marketing to digital content creators, but they did not know how to go after the market. Intel’s corporate Market Research Group determined through quantitative research that because they had similar technological needs, and because many of them also played video games, digital content creators were essentially the same as video gamers, and could be reached with the same products and marketing materials. They recommended using a segmentation based on professional standing – professionals, prosumers (enthusiastic hobbyist creators who purchase devices that are close to professional-grade in complexity and quality), and mainstream (casual creators, who use low cost equipment to create basic projects) – to reach the market, with computational needs roughly distributed by status. By their thinking, professionals and prosumers used higher-end computers, and mainstream creators used lower-end machines. They advised the Desktop Business Unit to focus their efforts on mainstream consumers, people who take photos and videos of soccer games and birthday parties, for instance, because while they had lower computational needs, they were also the largest market and would, therefore, result in the highest sales numbers.

The Pathfinding Team, composed of social scientists located in a different Intel division, became aware of the interest in content creation within the Desktop Business Unit, and perceived a gap they were in a unique position to fill. Like the Desktop Business Unit, they had observed the increasing centrality of digital content creation in both professional and consumer contexts. Drawing on research done in prior months and years, including research conducted ten years previously about what was then called user generated content, (Faulkner & Melican, 2007), the Pathfinding Team had begun to discuss key behavioral shifts in content creation, and were tracing some of these across diverse research projects unrelated to the Desktop Business Unit. The Pathfinding Team had recently conducted a series of studies on professional creatives, Gen Z (the generation born in the mid-1990s to today), and solopreneurs (similar to entrepreneurs, but with a stronger focus on working alone or with a few partners, as opposed to hiring and building an employee base). These projects had been borne out of requests from other business groups and stakeholders, and in some cases were small explorations driven by the team’s own agenda of understanding emerging socio-technical relationships and their relevance to Intel.

The Pathfinding Team recognized the market research segmentation based on professional standing as insufficient to address the needs of the Desktop Business Unit, and perceived distinct differences between their own observations and the market research recommendations. They saw computational needs distributed more in terms of complexity of project, for example, than professional status, and doubted that digital content creators were satisfied with the industrial design of laptops and desktops that catered to the video game market. Since part of the goal was to sell more high-end desktop computers, and given the prevalence of phone and camera based editing among casual, and even some semi-professional photographers and videographers, reaching out to soccer moms and dads, even if they were avid picture takers and video makers, also seemed ill advised at best.

The Pathfinding Team approached the Desktop Business Unit, armed with evidence from their prior and adjacent work, and a point-of-view on the shifts occurring in digital content creation which became the basis for the Unit’s decision to sponsor ethnographic research, first in the US, and later in China and South Korea. The insights generated from this work led to an entirely new and more actionable segmentation rooted in contextualized user behavior that reshaped Intel strategy, motivated new partner projects with Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs), and drove new marketing initiatives.

Market segmentations hold a powerful position within companies to shape business strategy and key decisions. Prior to the 1960s, companies had largely understood markets in terms of affordability, with luxury brands aimed at higher income consumers, and lesser models with fewer features offered at lower prices to lower income consumers. However, a 1958 article by Pierre Martineau argued that social classes differ profoundly in how and where they buy, not only along economic lines, but also in terms of symbolic value (in Cohen, 2004; 238). By appealing to narrower subgroups within a mass market, companies aim to link their brands not only to the practical needs of consumers, but also to their identities and sense of who they are as people. Where successful, market segmentations can be extraordinarily powerful.

Today, segmentations are typically owned by market research teams at corporations and are generally created by clustering attitudinal responses to questionnaires in order to identify different target groups of consumers (e.g. Flynn et al., 2009); these segments are then used to determine prioritization of different features and to inform decisions about the product design and marketing approach. Such methods are effective in that they reduce complexity in ways that make them easy to grasp and use as a framework. However, this same reductive quality can lead to misguided decision making and is often in tension with ethnography, with its attention to complexity. This case study brings another perspective to the relationship between market segments and qualitative insights about people, demonstrating the capacity for ethnography, as Marta Cuciurean-Zapan argues, to enable new kinds of representations (Cuciurean-Zapan, 2014). Further, it demonstrates the value of maintaining ethnographic capabilities within the corporate structure in supporting such interventions by providing the necessary internal knowledge structures, and identifying pivot points out of prior research that would not be possible when research is sourced from a variety of ad hoc sources.

This case study traces the process through which the Pathfinding Team identified a critical research gap, created the opportunity for an ethnographic intervention, and executed the study, leading to a series of new insights and ways of thinking about digital content creators as a market. The case study subsequently addresses how the Pathfinding Team worked with the Desktop Business Unit to represent the insights in ways that were both accurate from an ethnographic point of view, and relevant and actionable for the corporation’s business partners. Finally, the case study reflects on the impact of this project, and the factors making that impact possible.

PART 1: CREATING AND DRIVING THE OPPORTUNITY

Initially, the Desktop Business Unit was not fully aware of work taking place in the Pathfinding Team relevant to the topic of digital content creators. They were, however, struggling to figure out what to do with the corporate market research findings that were not clearly actionable. While that work divided the market of digital content creation into segments based on professional status, and time spent engaged in content creation activities, it did little to point toward what matters to content creators, and the factors that shape their computational needs or purchase decision-making practices.

When the Pathfinding Team approached the Desktop Business Unit and positioned its capability by presenting an initial point of view about the shifting context of digital content creation, they focused on past research about young creators (Gen Z), professional “creatives,” and solopreneurs in business ecosystem landscapes. This point of view was based on three key points: 1) that digital content creators had grown as a market segment through shifts in the PC-based software and hardware ecosystem that specifically targeted young creators, 2) that the youngest segment of PC users (Gen Z) were increasingly oriented not just around content consumption, but around content creation and, 3) that the rise in the US contingent workforce was likely to bring new urgency to the suite of hardware tools that enabled larger numbers of digital content creators to professionalize. The leader of the Pathfinding Team explains,

We approached the who ran the Desktop division with the desire to do limited pilot ethnographic research in the US because we believed that the work, along with secondary research, could provide an initial perspective on digital content creators that would give us, and the Desktop organization, the basis for making a decision on whether or not there was a potential opportunity with this particular population.

This evidence, presented to the head of Intel’s Desktop Business Unit, showed that major shifts were happening in the realm of digital content creation, and it became the basis for the Unit’s decision to support an initial research phase in the US. The Pathfinding Team was asked explicitly to return with more than “stories about people.” The business unit wanted actionable recommendations. The Pathfinding Team responded to this request by using stories and insights generated in that first phase of research to create an initial differentiation of content creators in terms of their orientations toward technology, including their interest and willingness to delve into technical details of hardware and software. The insights generated in that first phase led to an expansion of the project to include ethnographic research in two additional countries, a business ecosystem analysis that looked at the start-up activity around digital content creation, and a small online survey (n=150) on computing platform preferences designed to validate and support the ethnographic data. Eventually, the work resulted in an actionable market segmentation of digital content creators. This paper focuses on the ethnographic research portion of the study.

METHODOLOGY

After gaining the go-ahead to conduct a qualitative research project, the Pathfinding Team decided to focus their research on professional content creators – people who earned a living, or were trying to earn a living, through creating and distributing content, and on young Gen Z creators working toward making a name for themselves in digital content creation, some with professional aspirations, and some for whom the value lay elsewhere. The team defined digital content creators as people who make creative assets, mostly with a visual component, requiring high computational power. Representative job roles of this type of creation include filmmaker, music producer, and multimedia professionals (such as virtual reality & video game artists). Since the goal of the Desktop Business Unit was to sell more high-end, compute-intensive PCs, the decision was made to concentrate on people who need that type of machine in order to do their work.

The Pathfinding Team conducted research first in Los Angeles, and later in Shanghai, and Seoul. Los Angeles and Shanghai were chosen as field regions because they attract a wide array of creative professionals, and have strong infrastructures for supporting creative work. In recent years, Seoul has come to be equally recognized as a global influencer of pop culture and creativity, but its selection was driven at the request of the Desktop Business Unit who had a business interest in the region already. The regional and cultural differences helped identify key pain points that spanned across the professions, and provided insights into contrasting purchasing behaviors.

The team interviewed 55 participants: Los Angeles (n=21), Shanghai (n=18), and Seoul (n=16). This sample size was necessary to produce a diverse range of experiences, drawing from professionals who identified their primary work as follows in the list below.

- Video Post Production (10)

- 3D Modeling (10)

- Virtual Reality Building (10)

- Audio Production (7)

- Filmmaking (9)

- Social Media Broadcasting (5)

- Graphic Design & Photography (4)

Across all of the regions, the Pathfinding Team was specifically interested in understanding the perspective of creators who need to make their own decisions about the technology they use, which resulted in a focus on sampling solopreneurs. A solopreneur is an individual who combines the flexibility of freelance projects with the structure and brand building of someone who operates their own business. They work alone or in very small (under 10 people) companies, and have to act as their own information technology (IT) department. This type of professional was of primary interest because they necessarily focus on both the creative production of their work, and the best tools, technologies, and resources to support their endeavors. This is in contrast to creative professionals who are employed at a medium to large company that sets up the IT infrastructure and provides the financial investment in the equipment on behalf of the worker.

To be included in the study, research participants needed to use a laptop or desktop computer they selected themselves, and they needed to make money from content creation. The team was not looking for hobbyists. In each site, the team also sought out Gen Z (aged 12 to 19) content creators who were trying to generate value out of their creations – either social capital or monetary compensation. The team included Gen Z participants as they wanted to better understand the relationship between the behaviors and concerns of professionals, and those of young people who were serious about content creation but not – or not yet – professionals.

Participants were recruited using snowball sampling methods which included reaching out to content creators participating in online meetup groups, contacting media professors to refer former students, and posting recruiting advertisements on professional networking sites such as LinkedIn. For Shanghai and Seoul, the Pathfinding Team relied heavily on the personal networks of their fieldwork partners because without a one-degree of separation connection there would have been deep skepticism and mistrust by potential participants as to the legitimacy of the request.

The Pathfinding Team conducted three-hour ethnographic interviews with participants at the primary location where they work. For most of the sample, this was either their home (sometimes with a specific home office area such as in Figure 1) or in an office building. One participant specifically sought out hotel lobbies that he found architecturally interesting to use as a backdrop inspiration for the theatrical stage models he digitally crafted. The interviews followed a similar structure of having the participants talk through their personal and educational backgrounds related to their profession, and a project demonstration or set of work examples that showcased their workflow and process. In-depth, open ended conversations covered the level of computer processing power creators needed, the types of software applications they use, and how they came to make those determinations. From these areas of focus, the team gained a deep understanding of how independent digital content creators think about the role of technology in their work.

Figure 1. A game developer who aspires to create virtual reality worlds in Seoul, South Korea.

The primary research questions were:

- What motivates their content creation? What excites them?

- What is their background? How did they get here?

- What are the ranges of hardware and software used by content creators and what are their workflows?

- How do they make decisions about what hardware and software to acquire and how do they acquire it?

- What drives them to refresh or change their computing systems? What is critical to their business?

- What are their computing pain points? What value propositions do they identify with?

- How do they make money and create value?

- What new technologies and new interaction modes interest them? What capabilities do they currently lack?

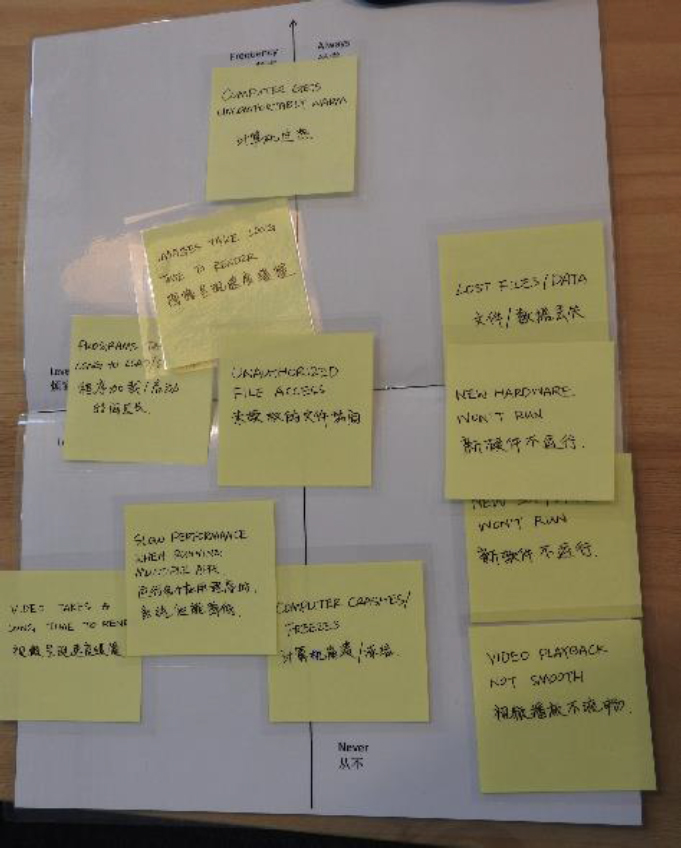

Research participants also completed a card sorting task with 15 different pain points about using desktop computers that had been provided by the marketing team, and blank cards where participants could add their own challenges. Participants sorted these pain points on a grid that represented the level of annoyance they experienced with the pain point, and the level of frequency encountered in their work (see Figure 2). This type of structured activity, completed at the end of the interview, provided a useful opportunity to explore the prior behaviors from the interview in relation to the types of trade-offs that the Desktop Business Unit wanted to understand better.

Figure 2. Card sorting activity of computing pain points mapped out by Level of Annoyance & Frequency Encountered.

Substantial time was also spent with research participants outside the interview setting, and in other contexts relevant to them, although not always with those who participated directly in the study. One member of the team participated in a weeks-long mixed reality development course. The team attended a professional conference for content creators, ate meals with participants, and immersed themselves in the content creation culture in each country. For example, in both the US and China time was spent in co-working spaces to understand how solopreneurs use these environments to create business connections. In Shanghai, the team also went through the sales process of buying a computer just as several participants described doing themselves (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Buying a PC in a Shanghai computer mall, the computer consultant advised the team to buy less expensive parts for our proposed virtual reality activity.

In Seoul the team was able to revisit two research participants that had been part of multiple Intel content creation studies dating back ten years, and who had formed collegial friendships with the Intel team. In one case, the team was able to attend a rehearsal for a multimedia experience inside the walls of the largest royal palace in Seoul, as one of the content creators projected images on the palace’s facade. These additional activities provided a richer context for relating the interview data to first-hand experiences, and helped the Pathfinding Team more deeply understand creators’ perspectives on how technology supports their work and professional goals.

Using Workshops to Expand the Project and Refine the Tech Orientations

The Desktop Business Unit stakeholders had not previously worked with ethnographers, so the Pathfinding Team set up project timelines to have constant feedback loops, both through workshops and organizing opportunities for stakeholder participation in the interviews with research participants. These check-ins served important functions: 1) they brought the stakeholders into the ethnographic process of analysis, 2) they allowed the team to take the time needed for this project while maintaining a strong communication line with the stakeholders, 3) they gave the Pathfinding Team the opportunity to incorporate a deeper understanding of the stakeholders’ concerns into the research itself, and 4) they enabled a staged expansion of the project over time as the Pathfinding Team built trust and credibility with the Desktop Business Unit stakeholders.

By bringing stakeholders into the analysis, the team created a space for the stakeholders to share reactions and perceptions about the research data which was used by the team to refine the segmentation. In order to shift their assumptions, stakeholders had to deeply absorb the data themselves and experience it; this would not have been possible had the Pathfinding Team created a set of finished insights. With workshops built into the process, the team was able to co-create insights with stakeholders that could only emerge out of the conversations and reflections that were shared together.

One Desktop Business Unit stakeholder who participated in interviews at a commercial video editing house was so transformed by the fieldwork experience that he continuously referenced stories of the participants throughout the workshops and follow-up conversations. The insight that the stakeholder found most surprising was learning that the labor intensive part of post-production (transcoding videos) was offloaded to junior team members who were using computers that were too slow for this type of work–yet all the buying decisions were made by the creative lead who did not realize how slow the process was for the support team. By participating in the fieldwork directly, the stakeholder internalized the importance of job roles, and power relationships, in new ways as they related to the Desktop Business Unit goals.

The project was structured as such over a three month time period:

Table 1. Timeline for Interviews & Workshops

| Timeline | Activity & Outcome |

| Month 1 | USA Fieldwork Collecting insights about digital content creators, identifying and understanding behaviors around workflows and the use of technology. |

| Month 1 | Workshop 1 – Introducing the Data Draw stakeholders into directly working with the stories and insights about computing pain points. Test the idea of the tech orientation segmentation in its early form. |

| Month 2 | China & South Korea Fieldwork Validate the structure of the tech segmentation in completely new geographies and identify differences in participant behavior that may be impacted by cross-cultural factors. |

| Month 3 | Workshop 2 – Diving Deeper Translate structure of segmentation into actionable business activities, such as marketing plans and talking points for executives. |

After completing fieldwork in Los Angeles, the Pathfinding Team organized and analyzed the research data into an initial set of insights that highlighted key user stories and responses to initial stakeholder questions. These stories were crafted into user profiles which consisted of photos, quotes, and relevant points about the participants’ behaviors and technology use described in detail.

The team met and reviewed perspectives on each participant, and explored common themes. These themes emerged from the profiles, participant workflows that examined bottlenecks and frustrations with hardware and software, and they identified several different motivations for the types of creative work valued by the participants. Some participants placed a stronger emphasis on developing their work solely as it suited their artistic sensibility (often expressed by Gen Z participants), whereas others, like one South Korean audio musician, felt grateful to have a paying job producing music for video games, even if it wasn’t artistically challenging. He was satisfied by the fact that he had “real work” as an artist because it demonstrated to his parents that he was successful, despite their initial reservations about his career choice. Along with more practical findings about work practices, the amount of money spent on computers, and where participants purchased devices, the values expressed by research participants led the team to create initial insights linking technology choices to a broader sphere of influence based on expectations for how creators wanted to be perceived by others such as family and professional peers. This initial set of data impressions was organized into slides to be shown in the workshop meeting, but also printed out in order to encourage the stakeholders to annotate and mark areas of interest. The Pathfinding Team structured the first workshop on the following topics:

- 1) Generate conversation by sharing participant stories that emphasize different dimensions of interest:

- a) What does the technological environment of a creator look like?

- b) How does a creator learn about new software and hardware tools?

- c) What is the workflow and collaboration process of a creator?

- 2) Activate analysis with frameworks that were created from the initial internal analysis (Tech Orientation framework)

The workshops succeeded in helping the research team test stakeholders’ comprehension and perceived actionability of the technical orientation segmentation. The workshops also provided the stakeholders the space to insert their own point of view and point to areas where they wanted to know more. One contested topic was the relevance of the Pathfinding Team’s feedback that even Tech Whizzes, technically savvy and often highly skilled users who enjoyed researching, talking about, and building out their own hardware and software configurations, complained that the CPU component sold by Intel was extremely difficult to update and replace as a new part. The Pathfinding Team had anticipated that this issue would be considered a priority topic to be analyzed further, but the head of the Desktop Business Unit immediately dismissed this finding as well-known and not an insight that he considered actionable at that time. These types of discussions helped ensure that the recommendations and next steps being offered by the Pathfinding Team would be accepted into the working plans of the stakeholders. It also facilitated a level of investment in the project by stakeholders who felt and saw their concerns actively taken into account in the execution of the research and analysis, and enabled a staged expansion of the project over time as stakeholders came to see the value of it, and asked for more.

PART 2: DEVELOPING THE SEGMENTATION

Understanding Content Creators by Behaviors

Ethnographic fieldwork exposed differences among professional digital content creators that led to the conception of a new market segmentation. The research conducted by the Pathfinding Team was substantially different from the research used by the corporate Market Research Group in forming their segmentation, resulting in a new way of thinking about the market. The Market Research Group had used a quantitative survey to look at the size of the market, and to quantify what content creators were doing, but not why or how. The resulting segmentation was based on creators’ professional standing (professional, prosumer, mainstream), and not on their workflows and values. The Pathfinding Team used qualitative, in-depth research to understand content creators’ behaviors, motivations, and attitudes. The Pathfinding Team segmentation and the Market Research Group segmentation had very different inputs which resulted in completely different outputs.

Early on, the Pathfinding Team was struck by stark differences among the content creators in behavior and feelings about technology. While some research participants passionately delved into the distinctions between generations of CPUs identified by corporate code names, and reminisced about their first forays into building their own PCs and hacking firmware, others were emphatic in their total lack of interest in such details. The less technically focused creators wanted to know as little as possible about computer specifications. They wanted the right computer to get the job done while taking up as little of their time and attention as possible. Insights from the life histories of both professional and Gen Z participants made it increasingly difficult to support hard distinctions between professional and non-professional creators. At the same time, insights showed increasing differentiation among professional content creators in terms of how they related to technology and technical specifications more broadly.

Figure 4. Tech Whiz CEO of a VR startup in Seoul, South Korea (left). He built all the computers used in his small company of eight people.

However, other professional creators bought their computers off the shelf with some help from a friend, colleague, or store employee; the team called them Minimalists (see Figure 5). When asked about computer specifications for components like the CPU, GPU, and RAM, one American commercial video editor said, “I have no idea what any of that means.” Another participant described her purchasing process as going through the drop-down menus on the product web site and selecting the most expensive options because given her work, she knew she needed “the best.”

Figure 5. A Minimalist TV and film editor in Seoul, South Korea who consulted with friends and mentors when buying technology for her studio. Creating computer graphics is her least favorite part of her job.

In between these two extremes were creators who might have preferred not to know anything about technical specifications, either for lack of time or lack of interest, but the nature of their work made it impossible for them to use off-the-shelf computers without any customization. Specialized technical variations between components or models were critical to their projects, so the team called them Specialists (see Figure 6). Specialists had learned technical specifications relating to their own creative objectives. One American audio composer said, “The graphics card isn’t as important to me, so I don’t know what card I would get, but 1 Terabyte of storage is not enough for all my sound files, so I have to get more chassis.”

Figure 6. A Specialist audio musician in Shanghai needs to connect keyboards and other hardware extensions that require him to understand technical details; he would rather just focus on the creation of music.

This model was a major change from how Intel had traditionally thought about consumers. The technology orientations cut across professional standing; they apply to creators whether they are professionals, prosumers, or mainstream creators.

In collecting biographical stories of how participants came to be professional content creators, and in interviewing Gen Z creators, for whom the value they derive from their activities rarely qualifies them as “professional’ or even “prosumer,” it was clear to the team that these orientations cut across professional standings. Tech Whizzes tended to be Tech Whizzes long before they became professional content creators, and many successful professionals remained Minimalists. While Specialists’ expertise tended to grow alongside the sophistication of their work, and was thus loosely linked to professionalism, it was significant to the team that the acquisition of knowledge was driven not so much by professional advancement as by the complex nature of the work they were trying to get done. Each segment has a different relationship to technical complexity – Minimalists do not want any complexity in their tools and systems, Specialists need complexity in certain discrete parts of their systems, and Tech Whizzes thrive on complexity across multiple machines, software programs, and other tools (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Technical Orientation overview to explain the differences between each segment.

The Pathfinding Team determined that professional content creators are more diverse than Intel previously thought. Professional does not always equal tech savvy, contrary to the company’s longstanding assumption. While taking into account the findings from the team’s pilot studies and past studies on content creation, it was clear that a mainstream, non-professional content creator is not always tech ignorant. There are degrees of tech literacy throughout the large market of digital content creators. Furthermore, the tech orientation framework proved to be a valuable tool in thinking about how to message to, and market to content creators. It is both a model and a finding that was a useful way for the Pathfinding Team to make sense of what they had learned, and communicate it to the rest of the company. It gave the team a way to talk about the research that was actionable.

Creators are Not the Same as Gamers – In addition to the insights around technical orientation, the research showed clearly that digital content creators are not the same as gamers. Contrary to a longstanding Intel assumption, digital content creators did not want to buy gaming PCs and would not respond to advertising and messaging aimed at gamers, even if they played games in their spare time. Creators (both professional and Gen Z) identified as creators, and wanted devices that were sleek, stylish, high-end and devoid of gamer-oriented ornamentation like flashing lights, skulls, and dragons. A Chinese industrial designer told the team, “I hate Alienware because of all the flashing lights.” An American 3D-modeler expressed frustration with computers optimized for his work saying, “What I’m buying is geared toward gaming, and it feels patronizing. I hate buying hardware from companies that look like they should be selling Airsoft guns.” Despite enjoying gaming in his free time, he did not want to do his digital content creation on a gaming machine.

Culture also played a part in participant attitudes about gaming and content creation. In China, for example, where career choices and purchasing patterns alike were more strongly shaped by professional and social role than by concepts of personalization, participants were particularly averse to computers designed for gaming, seeking instead those they felt were “best for design” which they perceived as categorically different from gaming machines regardless of technical specifications.

Cultural Differences – While the Pathfinding Team’s efforts were aimed at understanding digital content creation practices ethnographically and cross-culturally to tease out common patterns and concerns, understanding how these patterns played out in different geographical and cultural contexts was central. The Tech Orientation framework as a segmentation highlights relevant differences for the digital content creation market that cut across geographic boundaries. Cultural differences between someone in Los Angeles and someone in Shanghai were not relevant to the creation of the segments for the global market of digital content creators. However, as in the point made above regarding perceptions of gaming and design oriented hardware in China, the team also found important social and cultural variations. That material was used internally to talk about different go-to-market strategies and advertising methods and messages.

In China, for example, enormous value was placed on the newness of a computer. Content creators preferred to buy a less expensive, less powerful machine on a more frequent cadence rather than buying the top-of-the-line and keeping it for several years. The head of a Shanghai design start-up said, “We were planning to buy a 100,000 RMB computer, but we want to try the 10,000 RMB one first.” He hoped the much less expensive machine would be good enough for the short time he planned to use it. The value Chinese content creators placed on getting a good deal economically, coupled with their perception of quick cycles of obsolescence, led them to buy the least powerful, least expensive machine that could get the job done. They upgraded machines often because the next generation was expected to be better in both performance, and in the optics of success, where newness signaled to others that their business was doing well. In South Korea content creators tended to maximize their purchase and buy the best machine they could afford. A Korean virtual reality developer told the team, “I want my PC to be a beast.” Similarly, in the US, where “time is money” and the most expensive part of any project was the cost of human labor, content creators tended to buy the most powerful machine they could afford with the understanding that time saved on processing media translated directly into savings for the creator. In addition, even for non-professionals, generational product differences between computer processors were seen as so small and incremental that it was better to buy a more expensive, more powerful machine, and keep it longer.

One of the findings that surprised the team was the relative absence of Tech Whizzes in Shanghai. Regardless of a highly entrepreneurial spirit, and strong value placed on resourcefulness and economy (two values cited by many Tech Whizzes), and despite a few participants who mentioned having built computers from scratch in their youth, content creators in China did not tend to orient toward technology in this way. Why? The explanation for this lies in the confluence of social, cultural, and economic structures that undermine the financial and social value of being a Tech Whiz. From a socio-cultural perspective, Chinese communities place higher emphasis on the ties that bind people together than on self-reliance as an individual trait, as in the United States. Whereas in the United States, Tech Whiz stories about themselves emphasized both the economic advantages of “building one’s own,” and the satisfaction of individual accomplishment, for Chinese participants, there was no particular personal value or social capital associated with building a PC. Instead, participants often made purchase decisions on the basis of advice from a friend or colleague, and resourcefulness was demonstrated in collective ways, by leveraging the skills and ties of one’s social and professional network, rather than one’s individual accomplishments. The solicitation and giving of advice on the “best” device to buy served to strengthen the network ties between people. In addition, in the Chinese market, desktop computers are generally custom built by local sellers, who include the assembly of the system as a free service when purchasing a computer. Thus, Chinese buyers reaped the economic benefits of building their own, with neither the practical need nor any special social cachet attached to deep technical know-how. However, because PC sellers were generally outside the personal network of content creators, their advice was seen as untrustworthy. One Chinese social media broadcaster told the Pathfinding Team that she needed a more knowledgeable friend to go with her to the PC mall when she wanted to purchase something to make sure that she wasn’t cheated. Thus, the role of Tech Whiz in China is actually distributed across a number of actors including knowledgeable friends, colleagues, and custom PC sellers. Tech orientations themselves are not simply characteristics inherent to personalities, but a product of various cultural, social, and economic forces as well.

For Intel, the particulars that make Tech Whizzes rare in China are less relevant than the implications of the particular arrangement of social and economic dynamics that shape how content creators make purchase decisions. It means that influencers (knowledgeable friends and PC sellers) are extremely important, and that broad campaigns focused on technical specifications are less likely to be successful than word of mouth and branding efforts that focus on defining “best in class” for specific creation purposes.

IMPACT OF THE RESEARCH

“This wasn’t just a research project that sits on a hard drive.”

—Desktop Business Unit Stakeholder

The ethnographic research results had an impact on organizational structure, new product development, relationships with equipment manufacturers, marketing and advertising strategy, and the corporate culture. A new strategic planning group was formed to create and support a digital content creators market, and the work enabled Intel to expand the market for high-end PCs through new marketing messages and products (Figure 8). The digital content creator team was able to use the research results to help activate an ecosystem with key OEMs in the industry. In one example, Intel shared the research results with an important OEM customer. The OEM subsequently shared extensive research of their own with Intel leading to a deep level of end-user understanding that helped define features for an all-in-one computer product designed for digital content creation in the Chinese market. The research also led the marketing and advertising teams to create campaigns tailored to content creators, keeping in mind the segment was more creative, and less technical than previously thought. Intel partnered with a key independent software vendor to develop a marketing campaign using members of the content creation community (Figure 9). The campaign featured real-world content creation case studies based on the ethnographic research, and did not highlight technical benchmarks, a primary component of most previous Intel advertising campaigns for high-end computers. A crucial element of the campaign was a series of video portraits of key influencers from the Tech Whiz segment showing their work processes and tools. These highly polished video segments contained limited Intel branding and subtle marketing messages. The advertising campaign tag line was, “Intel Gives You the Power to Create Like Never Before.” The research had an impact on the culture of Intel as well. Inspired by the work of the Pathfinding Team, the market research team hired a consultancy to conduct ethnographic research, rather than quantitative research, in order to create a new segmentation of gaming enthusiasts.

Figure 8. Intel web site updated with focus on digital content creators.

Figure 9. Intel marketing campaign in partnership with OEMs focused on creators.

CONCLUSION

The case presented has two important points: (1) the necessity of understanding the rich textures of everyday life to create actionable frameworks, and (2) the importance of having an ethnographic research team in-house to keep a corporation capable of radical action in a dynamic world.

Primarily relying on ethnographic research to create a segmentation was a new experiment for Intel. Flynn et al. (2009) demonstrate the value of ethnography in market segmentation, beyond what statistical measures can create, by bringing real people, real data, and real experiences into the creation of an abstract, but actionable, segmentation framework. The research demonstrated to the company that a computer, camera, screen, hobby, and job are not discrete entities, but are part of deeply contextual experiences. The digital content creators research validated the importance of including ethnographic capabilities in the equation of creating a market. Surveys, focus groups, and text analysis concentrate primarily on what people say about things they do, buy or use, but fail to grasp the underlying structures that govern the realities of experience. In structuring the segmentation of a new market, it was important not just to capture correlations but to understand causation. The “why” of practices and behaviors help set up the boundaries for the market, as well as best courses of action to create the market. Answering the questions of “What does it mean to be a content creator?” and “How does one become a content creator?” led not only to powerful personal narratives, but to the framing of a segmentation. The team’s focus on both the social and cultural aspects of digital content creators helped to flesh out the market and move the work beyond individuals to the context of actions. While there were clearly differences in cultures, the team found the global communities of practice more influential in understanding the market drivers. The team created marketing and product recommendations separate from the segmentation to incorporate a more nuanced understanding of the cultural contexts of the digital content creators in places like South Korea, China, and the USA.

This case exemplifies a key advantage of having an in-house ethnographic team – the team can act without having to be asked to solve a problem. The in-house research team is able to do this in part because the team has a depth of understanding about the company, its products, services, history, and future strategy, which is not possible for vendors brought in to address discrete questions. Because the team is immersed in the company all day, every day, they are attuned to the company, its mission, values, and culture. In day-to-day interactions the Pathfinding Team had created trusted relationships with decision-makers that created openings for introducing alternative perspectives. Further, as evidenced here, in-house ethnographic research teams bring a wide range of previous work that can be reframed to be pertinent to the corporation’s current discussions, and can create informed, historical perspectives on strategic developments that often seem to operate ahistorically in ways that risk missing critical shifts. In this case, for example, previous research pointed to an overall shift from content consumption to creation, suggesting the professional standing of creators be deemphasized in relation to technical orientations when trying to understand the market. In other words, because the Pathfinding Team was able to bring to the table a history of studying digital content creation, it was easier for them to see the breadth of that shift, and the ways it brought content creators into the market who were different from the company’s vision of creators with high technical needs. Finally, internal research teams are not necessarily “given” a problem, but can develop their own point-of-view on a topic. External agencies can execute flawlessly when given a problem, whereas in-house research teams can reframe discussions and prevent the need for agencies to solve problems. While in-house research versus outside agency research offers trade-offs, a corporation that has a blended approach, like Intel, creates the greatest advantage for success.

ken anderson is an anthropologist and Principal Engineer at Intel Corporation where he conducts pathfinding research on social-technical areas like the changing nature of work, 5G, and Gen Z. Ken’s over 25 years of publications on research about culture and technology have appeared in computer, anthropology, and business venues. ken.anderson@intel.com

Susan Faulkner is a Senior Researcher and ethnographer at Intel Corporation where her work has focused on understanding the future of connectivity, the needs and practices of digital content creators, the engagement of girls and women with technology through making, and the role technology plays in daily social transitions.

susan.a.faulkner@intel.com

Lisa Kleinman is a Director of User Experience at LogMeIn where she and her team research and design tools for collaboration. Her projects focus on group dynamics as it relates to the future of work, metrics for assessing product effectiveness, and concept and prototype development. She previously worked as a Research Scientist at Intel Corporation. lisa.kleinman@logmein.com

Jamie Sherman is a Research Scientist and cultural anthropologist (Ph.D. Princeton, 2011) at Intel Corporation where her work has focused on emergent technologies from quantified self and wearable technologies to gaming, virtual and augmented reality. jamie.sherman@intel.com

NOTES

Acknowledgments – The authors would like to thank Maria Bezaitis, the driving force behind the project; Muki Hansteen-Izora, their teammate; David Kennedy, their key collaborator and stakeholder; and their intrepid research partners in China and South Korea, Afra Chen and Soo-Young Chin. They also wish to thank the many research participants who generously shared their time and their insights with the team.

REFERENCES

Cohen, Lizabeth

2004 A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. Journal of Consumer Research 31(1): 236-239.

Cuciurean-Zapan, Marta

2014 Consulting Against Culture: A Politicized Approach to Segmentation. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2014:133–146. https://www.epicpeople.org/consulting-against-culture-a-politicized-approach-to-segmentation/

Faulkner, Susan, and Jay Melican

2007 Getting Noticed, Showing-Off, Being Overheard: Amateurs, Authors and Artists Inventing and Reinventing Themselves in Online Communities. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2007:51-65. https://www.epicpeople.org/getting-noticed-showing-off-being-overheard/

Flynn, Donna K., Tracey Lovejoy, David Siegel, and Susan Dray

2009 “Name that Segment!”: Questioning the Unquestioned Authority of Numbers. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2009:81-91. https://www.epicpeople.org/name-that-segment-questioning-the-unquestioned-authority-of-numbers/