“I got verbals, but verbals don’t hold up in court….I need it in black and white.”

After Sheila submits hospital quality data to the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), reports indicate that her data hasn’t been received. She makes countless calls to the CMS Help Desk to get answers. They reassure her numerous times that they have her data, yet Sheila is insistent that she needs to see the change explicitly stated in the report. Sheila makes it her personal crusade to obtain material evidence because only written testimony will prove that her data has been submitted successfully and protect her facility from CMS penalties.

At a time when we are becoming increasingly reliant on data and technology as the ultimate bearers of truth, Sheila exemplifies how people become stewards of evidence in service to these technical systems. As she moves her facilities’ data through CMS’ error-ridden reporting system, the burden of proof is on her to provide the type of evidence acceptable to demonstrate her facilities’ compliance with federal quality of care standards.

Throughout our paper, we explore the different practices that hospital employees and vendors take to demonstrate their facility’s quality of care to CMS, identifying key elements of materiality, evidence and moral obligation. By weaving together their narratives of a responsibility to prove their truth to a capricious, data-driven system, with theoretical concepts of “bearing witness” and governmentality, we reveal the ways in which digital data falls short of being sufficient evidence and the dangers inherent in shifting blame from a body of government onto the body of an individual.

INTRODUCTION

There’s a waste crisis happening Ala Ajagbusi, a small village in rural Nigeria. In the absence of a public health infrastructure in the area, women find themselves sifting, sorting and managing waste for their household and community. One participant scoffs at the line of people defecating under the villages’ only power line,

“They are not even shy about it[…] But we don’t want cholera here.”(Abdulwakeel; Bartholdson, 2018). So she walks for over 3 miles with bags of detritus and human waste and burns the trash. Those who don’t adhere to the cleaning and waste protocols are deemed bad housewives. How does it come to be that morality, government policies and personal action become conflated in these strange arenas?

Similarly, in the pacific northwest, Sheila works for a hospital system where she is the sole employee responsible for submitting data on quality of patient care for 11 hospital facilities into QualityNet, a tool maintained by the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS). She feeds the data from the facilities’ Electronic Health Records (EHR) into QualityNet, a in which she cross-references emails and CSV reports to ensure that all of her files have been accepted by the CMS system and that there are no discrepancies between her files and the data in the CMS warehouse. She sifts and sorts through data and organizes it in a way so the delivery is acceptable to the system. She takes personal moral victory in navigating the complex multistep process.

These two women, on opposite sides of the world, are actually engaged in quite similar processes of Public health management. While the village woman takes pride in her visibly clean surroundings and long walks as proof of her compliance to complex protocols. Sheila creates and compounds similar visual evidence and proof of her facilities adherence to CMS strictures.

At a time when we are becoming increasingly reliant on data produced by technological systems for validation, Sheila exemplifies how “data and evidence” become tools by which people imbue themselves with moral and social authority over government policies and practices. Through this paper, we will examine these practices by Sheila and others, borrowing the concept of “bearing witness” from Anthropology of Religion to describe the knowledge production processes of hospital employees and vendors. We ultimately situate this witnessing within Michael Foucault’s governmentality framework, with CMS and the quality data reporting system they’ve developed as the invisible hand. By examining these themes through the joint theoretical lens of “witnessing” and governmentality, our paper will serve two masters. First, we will bring a thoughtful cross-section of critical theory and Anthropology of Religion to the EPIC community. Our hope is that by demonstrating how these theories fit within American healthcare quality, we will empower ethnographers within the community to identify similar patterns and view the labor of the individuals they work with in a new light. Finally, we will also challenge assumptions around what constitutes “evidence” within data-driven technological frameworks. By acknowledging individuals’ labor and materiality as playing a key role in proving compliance with quality of care, we reveal the ways in which digital data falls short of being sufficient evidence and the dangers inherent in shifting blame from capricious government processes onto the body.

METHODS

This article took a qualitative, multi-layered approach to data collection and analysis. The two researchers conducted a series of remote, semi-structured interviews with the two major populations involved in reporting quality of care data to CMS: hospital employees and data vendors hired by hospitals to submit data on their behalf. Beyond ensuring a diverse sample of both vendors and hospitals, the researchers strived to include participants from a variety of types of hospital facilities. With corporate healthcare systems (HCS) on the rise nationally, it was necessary to get the perspective of these corporate centers and employees from their associated facilities (Kaufman, Hall and Associates, 2016). However, the researchers also recognized the unique resource and staffing challenges of independent hospitals, particularly those of critical access facilities or rural, community hospitals. The researchers took a two-tiered approach to recruiting the diverse sample type needed for this study. Thanks to an existing relationship with CMS, the researchers sent emails out to a set of listservs that are used by CMS and the contractors that maintain QualityNet to communicate with hospitals and vendors. Those that were interested in participating filled out a survey aimed to aid the researchers in recruiting a diverse sample, filtering potential participants based on their role, type of facility, location and technical ability. In complying with ethics practices, all participants signed consent forms indicating their willing participation, and agreeing to allow their data to be used freely by the research team. Ultimately, this article brings together findings from 15 participants from 10 different organizations across the U.S., including four data vendors, four hospital systems and two small, independent hospitals.

The researchers began the interviews with broader questions about participants’ role within their facilities and involvement with quality reporting programs. Then the researcher dug in deeper, probing participants on their practices for handling quality data and recent experiences submitting data to CMS to understand the full lifecycle of participants’ interactions with quality care data, from the collection of this data to their final confirmation that their facilities have successfully completed the program requirements. By asking about participant experiences, they collected “thick descriptions” (Geertz, 1937) about their experiences and begin to gather emerging themes amongst participants. The researchers then augmented these traditional interview techniques with digital ethnographic methods that focus on observing themes in human interactions with internet-based technologies (Hine, 2000; Hsu, 2014). Researchers observed participants moving through QualityNet, the portal for complying with quality requirements and communicating with CMS, probing them on their experiences within and adjacent to the system. Finally, the researchers walked through a series of artifacts vital to demonstrating compliance with the CMS reporting program, such as reports and email communications with the CMS Help Desk.

Researchers captured and transcribed interview recordings and video of participants moving through QualityNet during the data collection process. Through analysis of these interviews and videos, researchers began to explore central themes of how these experiences shape hospital employees perceptions of their responsibilities and of themselves. The researchers took a grounded theory approach, splitting up the interviews and conducted the first coding cycle independently using a combination of in-vivo and thematic coding central to this approach (Given, 2008; Saldan?a, 2013). The researchers shared the results of their initial round of coding to discuss their findings and check themes before exchanging interviews to then verify their counterparts’ codes. This code cross-checking approach allowed the researchers to triangulate between sources and analysts to build trustworthiness in the qualitative data research and analysis process (Patton, 1999; Suter, 2012).

FINDINGS

Seeing is Believing

One of the methodologies hospitals workers and vendors utilize to signify compliance with quality care measures are through complicated and varied witnessing techniques. We define witnessing to include the hospital workers and vendors’ accounts of personal responsibility, the imperatives around seeing data with one’s own eyes, and the imperative of holding documentation in one’s own hands as demonstrations how these actors “bear witness” to their facilities’ quality of care. We borrow witnessing from its origins in Anthropology of Religion to highlight our participants moral relationship to the data and the materiality of evidence quality workers user to avoid penalties in the system.

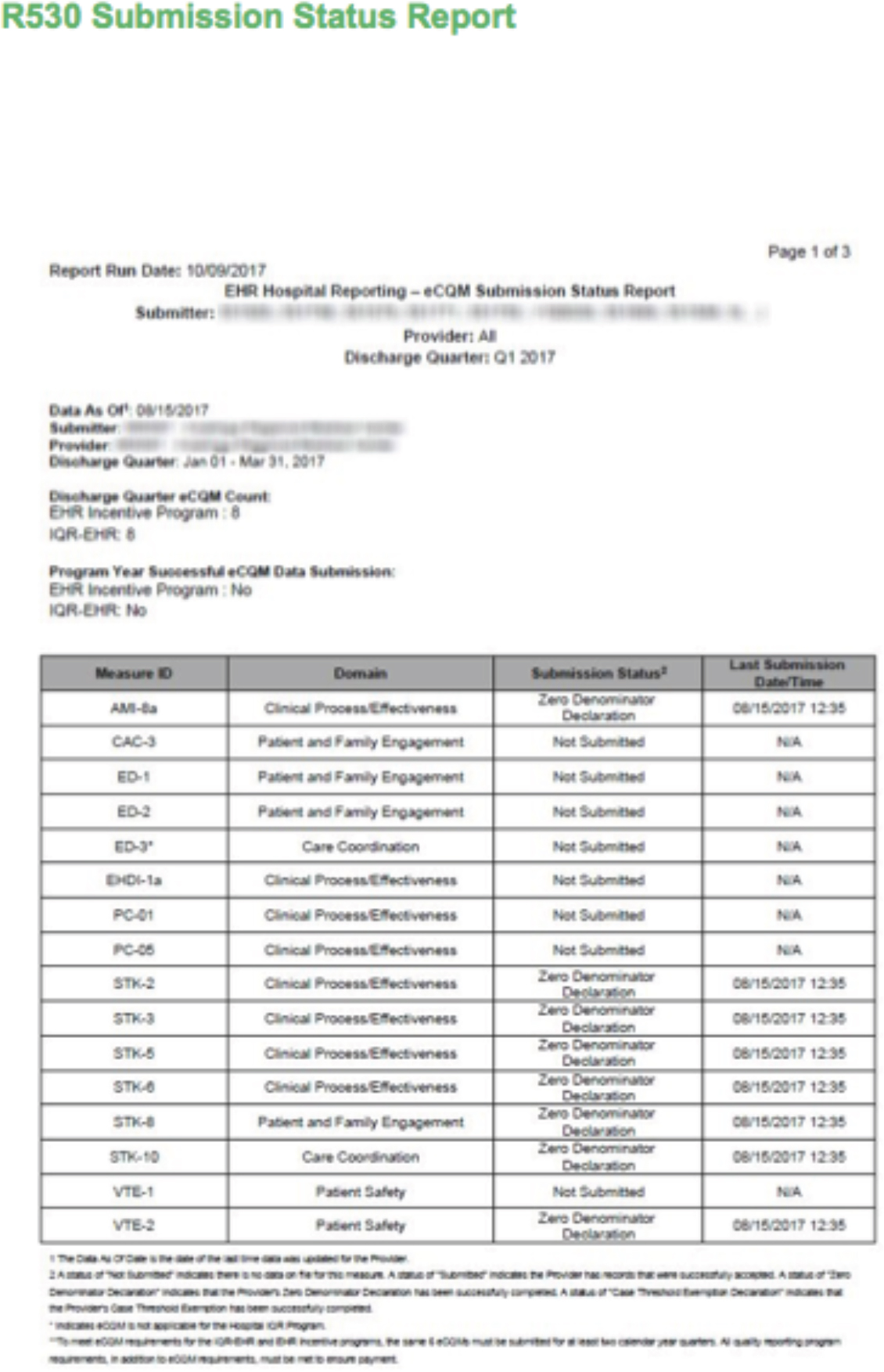

As our participants described reporting data to CMS, reports produced by the QualityNet system were cited as key visual evidence throughout the data submission process. These reports indicate whether their large zip files have been accepted and received by the CMS data warehouse without errors. Several of our participants described these reports as a “receipt,” “confirmation” or “proof” that they’ve successfully met program requirements and are done with the process. During the 2017 submission period for Electronic Clinical Quality Measures (eCQMs), one of the CMS reports was not updated to reflect new program changes. While some reports indicated that data had been received, the Submission Status Report — the primary source of “proof” according to our participants — indicated that facilities hadn’t met the reporting requirements. One section of the report bluntly states: “Completed 2017 eCQM Reporting Requirements: No.” Upon reading this, hospital employees spring to action. Sheila describes the labor she endures as a result to get the confirmation she needs:

“What are you talking about no? Did you get them or not? I have reports that say you got them, but you’re saying we haven’t satisfied the requirements…So here’s where a lot of phone calls had to be made to [the CMS Help Desk] and they were confirming for me multiple times, because I would wait a week and it wouldn’t be showing and that’s a lot of money to be risking. But they kept telling me, yes, it was fine.”

For hospital workers and data vendors working with hospital clients, reports serve as confirmations that their data has been accepted and they’ve successfully met program requirements. Notice here also that Sheila’s need for particular documentation after her verbal confirmations speak to clear delineations on the levels of input that could “make the cut” and count as evidence. Bill, a submitter at a data vendor, describes a similar experience with this report error.

“None of our submissions are actually complete yet because that report is outstanding. It’s extremely frustrating because it’s a report with one line. And we will be held to that as the submission vendor for our client because we don’t have the final report telling them that they’re done.”

The confirmation that hospitals have successfully completed requirements hinges solely on the materiality of reports and the visual confirmation that they provide. Verbal confirmation in itself it not enough. Despite ongoing reassurance that the mistake is within QualityNet and her facilities have met program requirements, Sheila is insistent. She won’t believe it until she sees it explicitly stated in the report. She describes these interactions as “verbals,” but, according to her: “verbals don’t hold up in court….I need it in black and white.” By negating “verbals” Sheila illustrates the ways in which hospital employees and data vendors must bear witness to their facilities’ quality of care in very particular ways. It is only through seeing this evidence with their own eyes that they feel reassured that their responsibilities are completed. Below is a sample Submission Status Report with visual cues vendors and hospitals look for to signal completion.

Figure 1: Sample eCQM Submission Status Report

By situating the work of Hospital Quality workers within discussions of witnessing, our goal is to also hint at the deeply moral imperatives placed on workers in the creation of “Quality” Data. The book of Acts in the Christian Bible is all about a particular type of ethical work. Before Jesus ascended into heaven, his last words were, “You shall be witnesses to me in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8, NKJV). The followers of Jesus testified, “we cannot but speak the things which we have seen and heard” (Acts 4:20, NKJV). Rooted in the Christian notions of testimony, and of the body, sight and experience as vehicle of knowledge production, witnessing is a deeply persuasive Western cultural form. Witnessing has long played an important part in rights advocacy. Its use grew in the 1990s, when testimonies proliferated in multiple genres and arenas in human rights advocacy. Organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières have created precise and specific methodologies around witnessing that grew out of moral obligations to testify to human rights violations. Redfield (2006) calls these instances of witnessing a kind of “motivated truth” toward socio-political ends. The significance of morally motivated witnessing becomes more apparent when the frame of reference shifts from advocacy causes such as the advancement of human rights to fully operational bureaucratic endeavors, like Hospital Quality Reporting. Here, the “motivated truth” focuses around the materiality of the evidence involved, and the cognitive load of excessive if not pointless process management. These aspects of reframing combine to create a different context for action, one constructed around bodies and paper trails as much as words.

“I have learned to keep track of everything on a system folder so should I get hit by a bus or win the lottery and leave, they can follow the crumbs that I left behind me.”

Sheila moves the data through CMS’s system, while perennially working to prove compliance with quality of care standards. However, the system itself is fraught with technical errors, so she creates a path of documentation that demonstrates every one of her actions within QualityNet. She makes sure that every email she’s received and report she’s run and errors she’s encountered throughout the submission process are available for anyone to see. Her hope is that in the event that a facility is audited, anyone can take her place and produce their own the documentation needed to prove compliance with the law. Sheila’s system folder demonstrates the ways in which hospital employees and vendors are instrumental in creating evidence. “Evidence” of quality of patient care is not simply reflected through the data alone, but is also demonstrated through the documentation process she manages and its potential to be followed by others. By introducing Sheila’s folder of documents, we begin to detect the types of knowledge production that hospital employees and data vendors engage in to create evidence of their facilities’ quality of care and how this type of knowledge production ultimately culminates in their roles as “witnesses” on behalf of their facilities.

Some participants, such as Judy, a data vendor who submits for hospitals around her state, saves a physical copy of every single one of these reports “historically, just for defense.” Through her system of archiving, Judy explains that she is creating a “paper trail” to slowly make the case that her clients have met requirements, with the literal “paper” within this trail emphasizing the creation of materiality being necessary evidence of compliance. Sheila also describes her self-named “Sheila system” of tracking CMS documents as part of her need to leave a trail. She explains: “I keep proof of each step that I did and that each step is satisfied, with the thought in mind that if someone had to reinvent what I did, can they follow that trail?” In both these cases, participants emphasize the need to elevate reports through archiving and documentation into a certain type of evidence.

As Elizabeth, a nurse and quality improvement specialist at an independent hospital in the midwest, tracks which of her files have been rejected by the CMS warehouse, she explains: “I actually print it off and attach it to that other report that I was talking about where it shows I have a rejected case. So that should I ever be asked, I can say: look I ran this report that says I have a rejected case. Here is my Submission Detail Report and here I have circled which case it was.” Through adding her own touch to these reports, she creates evidence that is again, only meaningful based on her relation to it. However, printing the reports in particular represents their transformation into materiality. She even takes a step back after going through the papers. “Wow, I didn’t know my file was that big,” she exclaims. She creates a type of evidence that could not only hold up in a court of law, but is also very tangible and physical. Participants across the sample integrated the necessity of materiality into their own knowledge production systems, describing printing out reports, emails and combining them with their own annotations, spreadsheets and physical individual actions. Judy tracks the communication from QualityNet on the status of her files through these extremely manual means:

“If there’s one that doesn’t [get processed], I have the paperwork on my desk that I know I need to follow up on a batch that we sent. And then if I don’t get an email back that says it’s processed, that paperwork stays on my desk until I get an email that says I can go ahead and look at the reports. It’s a manual process on my end that says I didn’t get any feedback on this so it hasn’t processed yet.”

Like Elizabeth, Judy is taking digital information on her files from QualityNet and prints them and physically moves them from one place to another so she knows where to follow up. It is only through this system that she actually knows where her files are in the process. In both these instances, hospital employees and vendors describe moving information that has meaning within QualityNet outside the digital system. They are bringing it into the physical world and attaching personalized practices to this information that makes it relevant and meaningful to them. In this way, they are taking the base “data” and turning it into the material knowledge that can be written about, that can be pointed at, and, most importantly, that can start to exist as an external thing.

However, the relationship between evidence and proof is a bit more complex. The data from QualityNet isn’t truly “information” or “knowledge” until these personalized practices and materiality is applied. While we heard a litany of terms from our participants to describe the information they archive from CMS, participants frequently used terms such as “evidence,” “proof” and “defense” to describe their archiving process. Ann, a quality director for a hospital system with seven facilities in the midwest keeps a physical “book of evidence” with all the reports. According to Ann, “the value of the report is really the protection of the facility, and CMS is known to be unforgiving unless you have documents to prove that the error is on their side and not on the facility.” She keeps this book of evidence “so if we’re ever in a payment year where we’re receiving a reduction, we have this to show that the error is on CMS’ end.” Similarly, Judy explains that: “If we had a situation where a hospital was denied payment and said it was because we didn’t submit their data. We have the paper trail.”

In both of these instances, hospitals and data vendors are imploring their employers and client to witness what they’ve seen, to look at the evidence themselves to see with their own eyes. It is through the labor of hospital workers and vendors, as they run, track, save and, finally, show rather than tell, that these reports become evidence. These reports only have power in their relation to the participants’ interactions with them. While the need to see and show certain CMS documentation as crucial to their role demonstrates participants “bearing witness” to their facilities’ quality of care, the power that these reports have in relation to hospital employees and data vendors begins to demonstrate how these actors are instrumental in creating this evidence. While the methods through which our participants witness their facilities’ quality of care may seem varied, personalized and even tied to a sense of moral obligation, every aspect, from data collection to final submission is in service of an inscrutable system of penalties dictated by CMS requirements. The introduction of penalties and their conflation with morality and governmental policy, houses most of the actions we’ve discussed in a framework of governmentality.

Believing is Doing

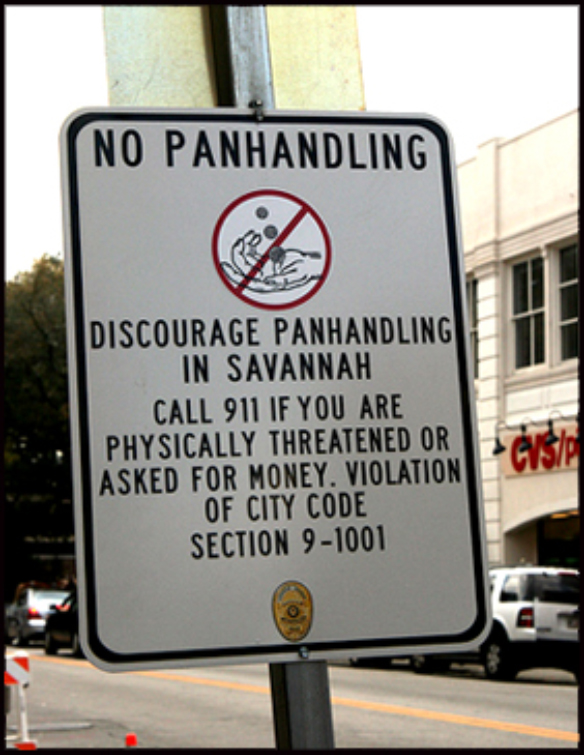

Foucault’s original essay on governmentality emerged from a lecture series that he presented at the College de France in the 1970s, which was concerned with tracing the historical shift in ways of thinking about and exercising power in certain societies (Elden 2007). Here, Foucault highlights the emergence of a new rationality of rule in early-modern Europe. Crucially, he introduces the term “biopolitics” to draw attention to a mode of power, which operates through the administration of life itself – meaning bodies both individually and collectively (Foucault 2003: 202). In doing so, Foucault illuminates an ‘art of governing’ that involves modes of practices and precise strategies that deputize citizens in service and execution of government policies . In addition, he articulates a mode of political government more concerned with the management of the population than the management of a territory per se (Jessop 2007). Consider this street sign (Figure 2) for a public place in Savannah, Georgia and this typed sign (Figure 3) that recently made national news in a Dunkin Donuts.

Figure 2

Figure 3

In both images, we see citizens being asked to enforce local policy and intervene on the lives of others or themselves for the benefit of the state. We posit that hospital quality workers have internalized formally external processes of evidence gathering for the sake of quality measure alignment. We examine how CMS structures and shapes the field of possible action of hospital personnel and vendors by giving meaning to these disparate evidence producing techniques.

In a public video recapping the events of the Quality Workers Conference, CMS suggests that quality workers be relentless in their commitment to quality reporting.

Figure 4: CMS Quality Conference 2018 Recap Video

We see here how policy needs get slowly transformed into moral and ethical imperatives. The anthropological field on ethics—conceived as explicit codes of conduct— is well rehearsed from Ruth Benedict’s Patterns of Culture (1934), Richard Brandt’s Hopi Ethics (1954), and Gregory Bateson’s Naven (1958) to Clifford Geertz’s Religion of Java (1960). Anthropologists have written about the strong moral codes that regulate Russian understandings of social networks and public assistance (Caldwell, 2004: 86) or the moral worth acquired by Nepalese women who live within the gendered restrictions of their villages (McHugh, 2004: 590).

According to Foucault, ethics can be understood as the actions or practices on the self with the aim of making, developing, or transforming oneself to reach a particular state of being (The Ethics of the Concern of the Self, 291). In other words, ethics involves the relationship of the self with the self and the activities that create and develop identities (Foucault, On Genealogy 263). Understood in this manner, ethics is not only a certain set of rules but rather consists of practices of self-transformation which may or may not be in relation to universal moral codes. Foucault describes these practices as technologies of the self, the activities which individuals undertake on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality (Technologies of the Self, 225). From Foucault’s approach, then, one becomes a moral person not by following universal rules or norms, but by training oneself in a set of certain practices (Widlock, 2004: 59). We place the quality worker’s “witnessing” work in service to this Foucauldian ethical work that enables governmentality.

Beyond creating materiality, these tracking practices mentioned above also begin to sow the seeds of an incredibly moral personal ownership of CMS processes. Another participant describes her tracking mechanism as a “Sheila system.” She manages a giant spreadsheet where she’s matched the Batch IDs and facility names and then continually updates based on the status of the uploads, whether or not there were errors, when the errors got fixed and final acceptance. By describing it as a “sheila system,” she has internalized this myriad of processes as her own, literally enshrining it with her name. While many of the tracking systems participants created are highly varied and convoluted, they are all in service of CMS and QualityNet. The system itself has attached a lot of meaning to a Batch ID, but this number is simply created by QualityNet and only has value within the system as they work to troubleshoot errors with the CMS Help Desk or figure out whether their files have been accepted. It doesn’t reflect the facility name, or information that hospital employees and vendors use to organize their own backend systems. Thus the different actions participants take to make this information meaningful to them actually serve as an example of the way CMS guides their actions toward compliance with measures and the complex technological system used for reporting these measures. The fact that Sheila has internalized this practice as her own further demonstrates elements of governmentality as she conflates state practices of compliance with her own personal practices. While she sees it as a “Sheila” system, it is in many ways a CMS system.

Foucault incited this theory of governmentality by examining the modern growth of procedures to produce and continue the life of the nation. Rather than focusing his analysis on concentrated power or sovereignty, Foucault was more concerned with how power is affected by disciplinary and governmental techniques that regulate and order the actions of people (Foucault, 1991). Even the most general definition of governmentality suggests that governance takes place from a distance as the power to influence the actions of others. CMS’s language around Hospital Quality measures, though increasingly mandatory, still claims to respect hospital choice. For example, CMS allows hospitals to make their own decisions about aspects and implementation of quality reporting. However this type of governmentality works from a distance through the encouragement (or direction) of ‘free conduct’. The extensive witnessing processes however aren’t producing true metrics of quality care nor do they protect facilities from financial penalties, low ratings or audits. They are instead simply in service to a punitive system of hospital measurement alliance.

Lucas Introna in his 2015 work analyzing the plagiarism site Turnitin.com talks about the dangers inherent in large data sorting and algorithmic processes and the types of “calculative “ practices that spring up around them. He finds Governmentality the best model to understand there new models of understanding practices that stem from sorting, managing and compiling data:

Governmentality allows us to consider the performative nature of these governing practices. They allow us to show how practice becomes problematized, how calculative practices are enacted as technologies of governance, how such calculative practices produce domains of knowledge and expertise, and finally, how such domains of knowledge become internalized in order to enact self-governing subjects.

As we house these specific practices within a tradition of witnessing, we recognize the moral weight that Quality workers put on their internalized systems of knowledge production and the preference for evidence one can touch and see. Like delicate nesting russian dolls, we use Foucault’s notion of Governmentality then to highlight the socio- political uses of such internalized complex practices. For example, the 2018 quality conference CMS officials remind quality workers that their goals create the system

Figure 5.

Despite the morality and personal responsibility that participants described having toward their role, all of the knowledge that they have produced, from reports to emails and spreadsheets showing the status of file submission, are ultimately in service of them building their defense for their facility . While participants placed immense value on the materiality of CMS reports and witnessing this proof firsthand, these reports don’t necessarily reflect reality. It’s possible to have successfully completed requirements and only get confirmation through a payment. The reports themselves don’t reflect evidence or compliance with CMS’ rules.

A hospital’s financial security relies on a full reimbursement for their Medicare claims. As Sheila’s experience illustrates, confirmation that facilities will receive reimbursement is synonymous with this report and discrepancies between what the QualityNet report tells them is true and their own knowledge about their submission throws a wrench of uncertainty into budgeting, causing panic amongst hospital employees. This unease about where one stands in the system is an essential prerequisite to the type of herculean ethical work vendors and hospital systems begin to employ. Built around the pretense of mitigating risks, hospitals create elaborate and often wholly personal and internal processes of knowledge production. These elaborate evidence gathering practices the ethical work of knowledge production serve the same purpose as the panhandling sign mentioned above. They both work to enlist the citizen in enforcement of regulatory policies with the facade of choice and free will. Part of Bill’s job as a data vendor is to assuage hospital clients of this fear when system errors arise.

“I have to play the good guy and say: no that’s really not how this works. There’s a process and we just have to follow and adhere to it and try to talk it up because they need to have something to tag onto as a sense of comfort because of what’s at stake here. That annual payment update. Once you start talking about that, people pay attention. And you know if you’re talking to a hospital that’s going to lose 2% of their reimbursement, it’s not going to be a pleasant conversation.”

In the face of all of this wrong proof, what is believing? If their reporting system itself is faulty, what does it mean to gather evidence? What do these practices mean? Proof it turns out, does not require truth as a necessity in the case of quality reporting.

CONCLUSION

The complex and varied practices by which hospital employees and data vendors manage their interactions with CMS represent a key role of their work as witnesses. These intricate knowledge production systems reflect these actors means of actually creating the evidence of their facilities’ quality of care – a type of evidence that is real in a very tangible and corporeal sense. Two of the most consistent practices described by participants as necessary to the their roles in hospital quality were: archiving and documentation of every interaction with CMS which ultimately culminated in knowledge production. We house these practices of knowledge production in the theoretical framework of Foucault’s Governmentality. We focused on how quality workers’ behavior is affected and framed by technologies of discipline, and order. We highlight how governmental policies, data technologies and individual techniques shape, regulate, and order the behavior of individuals toward the proliferation of government power. It is not new or novel that people take pride in their jobs or find personal fulfillment in doing things according to protocol. It is the fact that this pride and fulfillment can easily become economic or political weapons against other methodologies of data management. In the context of the Ala Ajagbusi village, women in the households socially organized themselves into an informal institutional arrangement to manage waste, but they also began to morally police women who didn’t comply. We hear echoes of quality workers explain away a mercurial system by questioning the thoroughness and systematicity of other workers processes. Power is at its peak when perfectly diffuse. Foucault (1980) argues “Its success is proportional to its ability to hide its own mechanisms”. The manipulation of work ethic is one mechanism by which power masks itself in this particular case. Making that which is constraining, tedious and potentially pointless-this process of witnessing we outlined above, or dragging human waste for three miles up a dusty road -appear positive and desirable, becomes the slight-of-hand we all must be vigilant of as we task ourselves to become better workers and better citizens

REFERENCES CITED

Saheed Adebayo Abdulwakeel, and Orjan Bartholdson

2018 “The Governmentality of Rural Household Waste Management Practices in Ala Ajagbusi, Nigeria.” Social Sciences 7, no. 6: 95.

Bateson, Gregory

1958 Naven : A Survey of the Problems Suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn from Three Points of View. 2nd ed. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Benedict, Ruth

1934 Patterns of Culture. Mentor Book. New York: New American Library.

Caldwell, Melissa L.

2004 Not by Bread Alone [electronic Resource] : Social Support in the New Russia. Ebook Central. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services

2018 “CMS Proposes Changes to Empower Patients and Reduce Administrative Burden.” April 24. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2018-Press-releases-items/2018-04-24.html

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services

2017 “IQR-FY-2019 CMS Measures Final.” November 1. https://www.qualityreportingcenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IQR_FY-2019_CMS-Measures_Final_11.1.2017.508c.pdf.

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services

2018 “Meaningful Measures Hub.” May 18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/MMF/General-info-Sub-Page.html.

Csordas, Thomas J.

2004 “Evidence of and for What?” Anthropological Theory 4, no. 4: 473-80.

Dave, Naisargi N.

2014 “WITNESS: Humans, Animals, and the Politics of Becoming.” Cultural Anthropology 29, no. 3: 433-56.

Derrida, Jacques., Thomas. Dutoit, and Outi. Pasanen

2005 Sovereignties in Question : The Poetics of Paul Celan. Perspectives in Continental Philosophy. New York: Fordham University Press.

Derrida, Jacques., and Marie-Louise. Mallet

2008 The Animal That Therefore I Am. Perspectives in Continental Philosophy. New York: Fordham University Press.

Foucault, Michel, James D. Faubion, and Robert. Hurley

1997 Power. Foucault, Michel, 1926-1984. Works. Selections. English.; v. 3. London: Penguin, 2002.

Geertz, Clifford

1960 The Religion of Java. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Geertz, Clifford.

1973 “Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture.” In The Interpretation of Cultures [electronic Resource] : Selected Essays, 3-30. New York: Basic Books.

Given, Lisa M., Editor, and Gale Group

2008 The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Hine, Christine

2000 Virtual Ethnography. London: SAGE.

Hirschkind, Charles

2001 “Civic Virtue and Religious Reason: An Islamic Counterpublic.” Cultural Anthropology 16, no. 1: 3-34.

Hsu, Wendy F.

2014 “Digital ethnography toward augmented empiricism: A new methodological framework.” Journal of Digital Humanities 3, no.1, 3-10.

Introna, Lucas D, and Malte Ziewitz

2016 “Algorithms, Governance, and Governmentality: On Governing Academic Writing.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 41, no. 1: 17-49.

Introna, and Hayes

2011 “On Sociomaterial Imbrications: What Plagiarism Detection Systems Reveal and Why It Matters.” Information and Organization 21, no. 2: 107-22.

Laidlaw, James

2002 “For An Anthropology Of Ethics And Freedom.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 8, no. 2: 311-32.

Li, Tania Murray

2007 “Governmentality.” Anthropologica 49, no. 2: 275-81.

Mahmood, Saba

2003 “Ethical Formation and Politics of Individual Autonomy in Contemporary Egypt.” Social Research 70, no. 3: 837-66.

McHugh, Ernestine

2004 “Paradox, Ambiguity, and the Re‐Creation of Self: Reflections on a Narrative from Nepal.” Anthropology and Humanism 29, no. 1: 22-33.

Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, Section 501b (2003).

Park, Crystal L.

2005 “Religion as a Meaning‐Making Framework in Coping with Life Stress.” Journal of Social Issues 61, no. 4: 707-29.

Suter, W.

2012 “Qualitative data, analysis, and design” In Introduction to Educational Research: A Critical Thinking Approach. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Redfield, Peter

2006 “A Less Modest Witness.” American Ethnologist 33, no. 1: 3-26.

Robbins, Joel

2004 Becoming Sinners [electronic Resource] : Christianity and Moral Torment in a Papua New Guinea Society. Ethnographic Studies in Subjectivity; 4. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.

Saldaña, Johnny

2009 The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles: Sage.

Widlok, Thomas

2004 “Sharing by Default?: Outline of an Anthropology of Virtue.” Anthropological Theory 4, no. 1: 53-70.