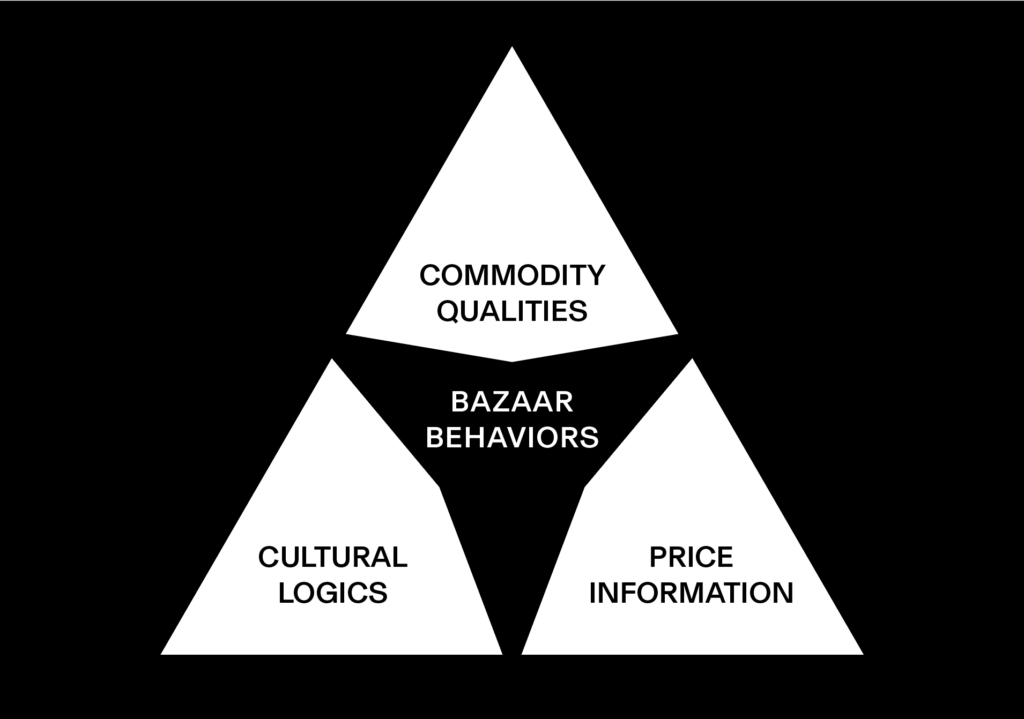

This paper demonstrates the importance of combining social and cultural analysis with pricing and economic logics to understand customer behavior in online commerce. It begins with a puzzle in the domestic market for hotels in India: in the context of a highly digitized market, with plentiful information about hotels and their prices available online, the majority of bookings are made offline and involve time-intensive, socially-mediated browsing and buying activities. By engaging with the anthropology of markets, and specifically the concept of “bazaars”, we show that the qualities of hotel rooms as commodities, and the cultural and price information logics at play, explain why Indian travelers favor friction in the search and booking process. While this paper is concerned with one specific commodity type, in one specific (albeit highly plural) market context, we conclude by outlining how we can generalize our analysis of bazaar behaviors to enrich our understanding of online commerce more widely.

“A main characteristic of our society is a willed coexistence of very new technology and very old social forms.”

—Raymond Williams, Problems in Materialism and Culture

INTRODUCTION

Sachin, a 22-year-old from a small town east of Mumbai, now living in the city’s northern suburbs, was excited to travel with his male friends to the beach resort state of Goa. It would be the first trip the group had taken together, eagerly anticipated and carefully saved for, and as such the stakes were high.

Sachin took on the responsibility of figuring out where the group should stay. As a member of India’s digitally savvy youth, he is the proud owner of an iPhone 6 on which he has a variety of travel-related apps. He was determined to find a decent hotel in a great location, close to bars, restaurants and beaches, while also mindful of his group’s tight budget.

A month before the trip, research began in earnest. Sachin trawled YouTube travel vlogs to understand the particulars of different locales. After deciding on a specific destination, he turned his attention to places to stay. He searched for hotels online using both Booking.com and the indigenous app MakeMyTrip, comparing many hotels to get a sense of the kind of quality he could expect for his budget. Narrowing his search, he identified three promising options that met his criteria. Sachin phoned each hotel to confirm the facilities and availability listed online. Content that he had carried out due diligence, he reserved all three hotels on Booking.com without paying in advance.

After traveling to Goa on an overnight train, the group visited each reserved hotel in turn. They surveyed the surrounding area, the general ambience of the hotel, the “crowd” staying there, and the quality of the rooms. A clear favorite emerged. Satisfied that they had the right hotel in their sights, Sachin discussed the price at the front desk and negotiated with the manager to secure inclusive breakfast. On discovering that the price quoted in person was more expensive than the rate at which he reserved the hotel a month earlier, he informed the manager that he would book via the app, and as he did so, he promptly released the other two advance bookings.

Sachin’s story presents a puzzle. India is a rapidly digitizing economy, where over 750 million smartphone users have ready access to all of the information and reservation tools that might be required to book accommodation online. Investing considerable time in advance online research and phone enquiries, yet still arriving without a hotel confirmed and proceeding to spend precious vacation time walking from one hotel to the next to carry out in-person inspections, appears intentionally and perplexingly full of friction.

In fact, Sachin’s story is not unusual. In May 2022, Stripe Partners was commissioned by Google to understand the domestic tourism market in India, with a focus on lodging. We carried out four weeks of immersive ethnographic research across six regions of India, meeting over 60 travelers, 10 hoteliers and 24 industry experts. We found that only a minority of travelers finalize their booking online in advance. Using online travel aggregators (OTAs) for price benchmarking, reserving multiple hotels, and evaluating hotels in person before booking were common practices, along with other friction-filled behaviors such as phoning hotels to confirm information found online and negotiate over price, flexibilities and extras. Our observations were supported by large-scale data: a 2020 industry report found that 65% of hotel bookings in India were made offline—over the phone, or as in the case of Sachin, in person (Phocuswright 2020).

This paper explores the apparent conundrum of Indian travelers opting for friction when searching for and booking hotels by using the lens of “the bazaar”. Tracing the historiography of the idea from Orientalist trope, via economic orthodoxy through to anthropological concept, we demonstrate the continuing relevance of the bazaar for making sense of present-day exchange behaviors in the travel vertical and beyond.

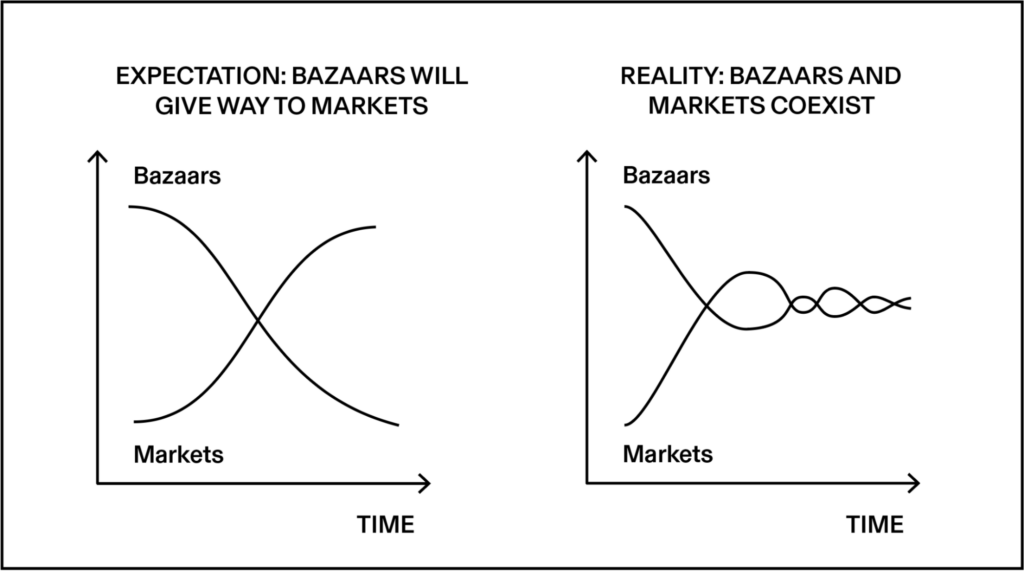

We argue that Sachin’s behaviors are not bizarre but rather bazaar-like, evoking the time-intensive, socially-mediated browsing and buying activities typically associated with physical marketplaces located geographically and historically in “The Orient”. Were colonial-era accounts and works of political economy to be believed, then such bazaar-like behaviors might have been expected to “evolve” in tandem with economic development into more market-like behaviors, with human interaction expunged in favor of seamless online transactions. This is evidently not the case.

At first glance, anthropological theory offers little more in the way of explanatory power. Clifford Geertz characterized the bazaar as a place where “information is poor, scarce, maldistributed, inefficiently communicated, and intensely valued” (Geertz 1978, 29). This does not immediately seem like a description of the online hotel market, where product and price information are plentiful and accessible. However, on closer interrogation, we see that specificities of the commodity qualities, cultural logics, and price information context in question paint a different picture—one that looks increasingly bazaar-like.

We, therefore, reanimate and extend this classical anthropological concept, showing its continuing relevance for understanding economic behavior in the digital age. As Geertz revealed the internal logic of “backwards” browsing and bargaining in the souks of Morocco, we demonstrate the eminent rationality of Indian travelers, like Sachin, in favoring friction when searching for and securing accommodation.

While this paper is concerned with one specific commodity type, in one specific (albeit highly plural) market context, we conclude by proposing that our analysis of bazaar behaviors might be generalized to enrich our understanding of online commerce more widely.

SECTION 1. BAZAARS AND MARKETS

1.1 The Bazaar as Orientalist Trope

The bazaar is a persistent figure in popular Western representations and the social imaginary of the Orient. Accounts of the Orient by travelers, ancient and modern, and feature films and television programs, frequently include vivid portraits of crowded, boisterous and labyrinthine spaces which overload their visitors’ senses.

Representations of the bazaar as more than mere marketplaces, but sites infused by “bizarre encounters, exotic commodities, and mystifying protocols” (Sarkar 2022, 63), have a sweeping historical and geographic range. The word bazaar itself is of Persian origin, was adopted into Hindustani and Turkish, and came to English via the Italian bazaara. In its middle and west Asian contexts, bazaar referred to marketplaces of both a permanent and more transitory nature. The word was adopted in Malay (pāsār) and repatriated to India with more mercantile connotations. The word’s circulatory range, Sarkar concludes, corresponds neatly to colonial (and current day) notions of the Orient (Sarkar 2022, 64).

If bazaars are “Other” to the Western market in sensorial and spatial terms, they are portrayed as very different in social terms too. The cast of characters to be found there is varied, and not all are simply there to buy and sell, or to do so honestly; as Sarkar notes bazaars are typically rendered as spaces inhabited by “merchants and buyers, touts and brokers, even healers and tricksters” (Sarkar 2022, 64). It is a space thick with social relations, where long-term and trusting relationships link traders and their clients (Geertz 1979) and co-exist with more transitory and contingent interactions, where honesty cannot be assumed, and trust is yet to be established.

Whatever their other differences, bazaars are usually distinguished from markets by the mode of economic exchange that occurs within them: bargaining or haggling1 is seen as the sine qua non of bazaars. Haggling is a process of price determination, typically entailing a verbal exchange wherein the buyer and seller negotiate a price acceptable to both for a specific transaction. It is contrasted with the fixed price exchange expected in modern markets, where prices are set in advance by the seller.

Haggling is “embedded in kinship and clientelist networks, affective structures of trust and reputation, religious observations and seasonal variations” (Sarkar 2022, 64). It is the idea that haggling is entangled in “thick” social and kinship relations that makes “economic transactions in the bazaar seem to be so much more—and, by the same token, so much less—than what they are in modern markets” (ibid.).

In other words, because haggling is a feature of economic exchange in contexts that are rich in social, moral and relational terms, it can be starkly contrasted to modes of exchange in which haggling is not (so immediately) evident. The implication is that in the apparently more evolved markets of “the West”, economic exchange occurs free of social, moral or other constraints: information about commodities is plentiful and transparent, prices are fixed, and exchange partners are absolved of the need to engage in the sort of practices that define the bazaar.

1.2 The Moral Economy Meets Markets with Moral Authority

We can begin to understand the emergence of the bazaar–market binary by turning to economic history, specifically the history of south Asia and the colonial encounter.2

Colonial accounts were written in a period after the market in the West had been through a set of institutional and infrastructural shifts (eg. contract law, and the obligations it placed on trading partners). These were accompanied by conceptual shifts that made values such as self-interest and competition central to the efficient execution of economic exchange:

“The assumption that the more abstract the economic contracts, and the more effective their stipulations in nullifying sociocultural opacities (social hierarchies, habits and customs, gaps in information, personal histories, etc.), the smoother the functioning of the market, became a governing principle. Emerging technologies, institutions, and instruments […] abetted and accelerated the processes of disembedding and abstraction, grounding the market’s moral authority in disinterested technicity.”

(Sarkar 2022, 66)

The juxtaposition of two types of trade—one thick with social relations, the other shorn of the complexities of social relations—cast one form as more modern than the other.3

One is “traditional and custom-bound, effectual and capricious” (Sarkar 2022, 67), the other modern, rational and objective. In this sense homo affectus was contrasted with homo economicus. Put differently, economic exchange characterized by the moral authority of the market was distinguished from markets exhibiting a moral economy.4

Cast in a temporal frame, this narrative implies a teleology: the bazaar is “discounted as an antecedent, partial, failed, incomplete version of the market; it is simultaneously the market’s malapropism, and its eternal not yet” (Sarkar 2022, 67). The implication is that the bazaar should disappear—that its form and associated behaviors will ultimately give way to the market and “truly economic” exchange practices. Such a movement presages the apparently inevitable transition from friction-filled to friction-less transactions.

1.3 Bazaars and Markets: The Hybrid Reality

On at least five counts, we call into question the distinction between “pure” economic exchange and more culturally or morally-infused exchange, and the assumption that the latter will give way to the former.

First, recent post-colonial scholarship questions the validity of the assertion that the colonial encounter was one in which socially-infused exchange practices collided with purely economic ones (eg. Ray 1995; Sarkar 2022). Further, and as Dipesh Chakrabarty notes in “Provincialising Europe”, the notion of diametrically opposed forms of economic exchange, one more evolved than the other, was central to the broader colonial project, an “historicist argument [that] consigned Indians, Africans and other “rude” nations to an imaginary waiting room of history” (Chakrabarty 2000, 7).5

Second, economic anthropology (eg. Carrier 1992; Miller 1998; Wilk 2018) has consistently demonstrated the deeply social and moral nature of much economic exchange, including fixed price exchange. Contemporary studies of shopping (Miller 1998) and consumption demonstrate that acts of economic exchange in the market are shot through with social, cultural and moral meaning. However, the ideology of market-based exchange acts to obscure that reality, concealing its moral dimensions in a discursive dressing of utility and price-maximizing individuals. Anthropologists Jennifer and Paul Alexander, who conducted fieldwork in Javanese markets (Alexander and Alexander 1987; Alexander 1992), suggest that “the idea of a fair price, based (somehow objectively) on the cost of producing goods pervades the West and obscures our perception of other forms of constructing exchange; price has become associated with the concept of objective value” (Herrmann 2003, 239). In short, the ideology of the market obscures the social, cultural and moral dimensions of exchange.

The third way in which we can challenge the unproblematic opposition of bazaars to markets, specifically, the idea that bazaars are pre-modern versions of pure markets, is to note that bazaars both as spatial or material forms, and as arenas in which distinctive economic practices are present, endure. They continue to be central to the mercantile and consumptive practices of populations across the world. Indeed, there is increasing academic interest in the ways in which they act as interfaces to more globalized markets and brands (eg. Deka and Arvidsson 2021).

Fourth, even in Western markets there are obvious exceptions to fixed price exchange. Bargaining is not uncommon but usually reserved for “big ticket” items such as houses, cars and other items that are purchased infrequently and seen as worth the time cost of negotiation. Equally, the information asymmetries that exist between buyer and seller for certain goods lend themselves to additional investigation by the buyer. Purchases in antique, second hand shops, car boot or garage sales (Herrmann 2003) might entail some back and forth to agree a mutually agreeable price. In that sense, specific sites of exchange come with the expectation that price is something to be negotiated.

Finally, online commerce—arguably the most “advanced” market form—is not limited to fixed price exchange. Auction sites such as eBay (or local variants such as OLX and Dreembox in India) often seek to accentuate, rather than obscure, the social relations between buyer and seller. Ecommerce sites such as Etsy make the elevation of social relations a defining feature of their proposition, while platforms like Gumtree and Nextdoor accent localized relations. Thumbtack, Upwork and other service-based platforms for tradespeople expect some form of bargaining.

The reality, then, is far more complex—and far more hybrid—than colonial and economic narratives would have us believe. The work of anthropologists, in particular Clifford Geertz, helps to elucidate the rationality of bazaars and associated social and economic practices.

1.4 Bazaars as Information Systems

Geertz conducted long-term fieldwork in Indonesia and Morocco, with his fieldwork in Morocco exploring in-depth the bazaar or souq in Sefrou, a town in the mid-Atlas mountains. Like most observers of such bazaars, Geertz was struck by the centrality of bargaining to their operation. However, he sought different explanations of it as a practice, and to see it as part of a broader cultural system. One departure from standard accounts in Geertz’s treatment of bargaining was to move beyond thinking about it, first and foremost, as a mechanism for price formation, as researchers such as Victor Uchendu had done:

“[H]aggling is defined as a process of price formation which aims at establishing particular prices for specific transactions, acceptable to both buyer and seller, within the “price range” that prevails in the market.”

(Uchendu 1967, 37)

Others stuck to this economically oriented script, seeing it in the context of complex and uncertain social relations:

“Bargaining […] serves an economic purpose, that is, to regulate prices in societies where suspicion and uncertainty as to the value commodities dominate.”

(Khuri 1968, 704)

And as they did so, they took their lead from Marshall Sahlins in casting bargaining in a generally unfavorable light, as a modality of economic exchange with negative behavioral dimensions. These observers cast it as “an unsociable form of transaction, because it is always conducted with varying degrees of cunning, guile, stealth” (Khuri 1968, 698).

Geertz’s corrective emerged from his interest in understanding bazaars—and markets more generally—as information systems. He was influenced by a new generation of economists who were at pains to destabilize the idea that markets are “complete”, or perfectly symmetrical in informational terms. Geertz was building on the seminal work of George Akerlof in his 1970 paper “The Market for Lemons”: “Consider a market in which goods are sold honestly or dishonestly; quality may be represented, or it may be misrepresented. The purchaser’s problem, of course, is to identify quality” (Akerlof 1970, 495). These treatments of markets sought to highlight the different information available to buyers and sellers.

A more “positive characterization of bargaining begins and ends,” Geertz suggested, “with the recognition that [bargaining] is a particular mode of information search, not a means for integrating prices” (Geertz 1979, 104). When people bargain, he asserted, they are seeking information on the nature of the thing being bought. Then, and only then, do they seek to establish its correct or fair price.

“The search for information—laborious, uncertain, complex, and irregular—is the central experience of life in the bazaar. Every aspect of the bazaar economy reflects the fact that the primary problem facing its participants (that is, “bazaaris”) is not balancing options but finding out what they are.”

(Geertz 1978, 30)

Geertz’s research into bazaars led him to distinguish between different forms of information search: extensive and intensive search. Extensive search is a means of benchmarking price and quality: it helps people survey the options available to them and determine the kind of goods they might expect to receive and for what price. Extensive search entails an initial “scouting” of the stalls or stores of multiple traders to see what sort of goods are on offer, and what price range exists. Having established some ballparks, the intensive search phase is about evaluating if a specific item has the qualities desired. It is the process of exploring the true nature of what is being sold.

“Search is intensive […] because the sort of information one most has to have cannot be acquired by asking a handful of index questions of a large number of people, but only by asking (and answering) a large number of diagnostic questions of a handful of people. It is this kind of questioning (and counter-questioning), exploring nuances rather than canvassing populations, that, for the most part, suq bargaining represents.” (Geertz 1979, 108)

(Geertz 1979, 108)

Intensive search is interactive and conversational, involving “thorough examination and consultation” (Uchendu 1967, 41). Buyers are typically permitted to inspect wares before they make an offer and certainly before they agree a final price and pay. They will likely question the seller to elicit information that is not explicit. Intensive search places a certain responsibility on the buyer to glean all the necessary information before agreeing a sale: “[t]he principle of ‘thorough examination’ enjoins the customer to “beware” of his choice” (ibid.).

Building on Geertz’s work, Alexander and Alexander identified another information seeking behavior: “a process in which the quality of the buyer’s information is evaluated” (1987, 54) and used to inform the subsequent negotiation. Their analysis focused on the seller’s assessment of the buyer’s information quality; however, we believe this idea can be meaningfully applied to the buyer’s assessment of the seller’s information quality. That is, the buyer uses the very process of consultation and negotiation to assess the quality (and trustworthiness) of the seller’s information. We call this meta search.

Beyond revealing bazaars to be information systems, anthropologists also added nuance to the characterization of bargaining in the bazaar, demonstrating that the practice involves more than price determination. Geertz drew attention to the importance of multidimensionality: that beyond price, quantity and quality are aspects of the transaction to be negotiated:

“Quantity and/or quality may be manipulated while money price is held constant, credit arrangements can be adjusted […] In a system where little is packaged or regulated, and everything is approximative, the possibilities for bargaining along non-monetary dimensions are enormous.”

(Geertz 1978, 31)

Through his reframing, Geertz challenged the idea of “bazaar behaviors” as backwards and showed them to be a highly rational means of navigating imperfect information. We now turn to examine these behaviors in the context of the Indian hotel market.

SECTION 2. THE INDIAN HOTEL MARKET

2.1 India, Development and The Domestic Tourism Market

India can rightfully lay claim to being the world’s most sophisticated digital economy. Outlining some of the technological developments of the last two decades, which have been driven by public sector initiatives and private sector activity, provides important context for the economic behaviors which the remaining sections of this paper explore.

A critical accelerant has been the flourishing of the telecoms industry. For example, the arrival of the telecoms company Jio, was a market-defining moment, initially offering free, and then low-cost, internet access via dongles. It is now the largest mobile network operator in India and the third largest globally with over 426.2 million subscribers (Reliance Industries 2021).

India is ranked seventh in the world for countries with the cheapest mobile data rates, at $0.16 per 1GB (Cable 2023), and with 750 million smartphone users (GSMA Intelligence 2021), India is now a mobile-first economy. GSMA Intelligence calculates that 81% of the population have a smart- or feature phone (ibid.). WhatsApp is, de facto, the communications layer for India, with 535 million active users and heavy use by businesses (Ruby 2023).

However, appreciating what’s known as “India Stack” is crucial to understanding how cheap internet access and rapid smartphone adoption alone have not powered India’s technological revolution. India Stack is a family of APIs, open standards, and infrastructure components that allow a user in India to demand services digitally. It has three layers: digital identification, which gives every resident a unique ID and enables them to prove their identity (eg. Aiyar 2017); data empowerment or trust through consent, which facilitates secure sharing of data; and interoperable payments through the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which enables fast, cheap and frictionless transactions (Carrière-Swallow et al. 2021). Combined, the layers of India Stack have lit a fire under the economy of the world’s most populous country.

These technology developments6 have occurred in the context of an economy charting a course to liberalization since 1991, with the country achieving 5.5% average GDP growth over the past decade (Morgan Stanley 2022). In the context of the travel market, rising prosperity has led to increasing car ownership, and the emergence of low-cost airlines has allowed India’s population to act on state and central government campaigns, such as Dekho Apna Desh or “See your Country”, exhorting citizens to explore their diverse country. In 2019, there were over 2 billion domestic tourist visits in India (Statista 2023). New forms of travel and holidaying run alongside long-standing journeying practices, such as the pilgrimages undertaken by India’s many religious communities.

In the context of rule by the nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) since 2014, technology infrastructure development has a strong indigenous flavor, mirroring some of the rallying calls of the independence movement, such as swaraj (self rule) and swadeshi (self-sufficiency). For example, the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) initiative—specifications designed to foster open interchange and connections between shoppers, technology platforms, and retailers—seeks to counteract the dominance of global ecommerce platforms in the country (Sethuraman and Ajith 2023).

The absence of domination by global brands in the Indian travel market reflects the strong indigenous flavor of these broader technological developments. India is one of the few places in the world where local online travel aggregators (OTAs) are used more widely than their global equivalents; MakeMyTrip, ClearTrip, Goibibo and OYO are more than equal rivals to Booking.com, Expedia and Hotels.com. However, global platforms such as Instagram, YouTube and Google Search play an instrumental role in all phases of the travel journey; from early stage inspiration and exploration, to more detailed research and price comparison. These platforms, and the information they provide, are lubricated by the heavy use of WhatsApp to compare notes with friends and family, plan trips and to interact with hotels. And it is these behaviors—both on- and off-platform—which we now explore in more detail.

2.2 Opting for Friction in Hotel Booking

If the natural evolution from moral economies with bazaar-like characteristics to markets with moral authority were to hold true then the strongly digital flavor of commerce in India, and in the travel market more specifically, could be expected to give rise to more thoroughly online and frictionless transactions.

Ethnographic research conducted in June and July 2022 with a team from Google Search that sought to understand the operation of the Indian lodgings market for domestic travelers, revealed a more complex reality. The browsing and booking behaviors of domestic Indian travelers we met strongly echo the bazaar behaviors described by Geertz, and Alexander and Alexander.

Extensive Search

Like Sachin who we met in our introduction, many travelers make use of a wide array of digital tools to gather information about hotel options. OTAs and Google Search are well-used, but not for final booking and payment. Rather, they are used to determine what sort of rooms are available in what sort of hotels for what sort of price. There is no “one stop shop” for hotel search—travelers tend to cast a wide net to compare options and prices, despite the effort this entails. One traveler reflected: “comparing so many platforms and applications takes up a lot of time and energy”.

Price benchmarking is an important early step in the hotel search process—this information can be wielded later in negotiations to secure a better deal. For example, 19-year-old Anil told us how he uses prices from OTAs to negotiate with hotels in person: “my budget is INR 1500–2000 but I’m looking to get a INR 4000 hotel. With the price from MakeMyTrip I can ask for a better rate at the first hotel. Then I go and ask at a few other hotels and find the best deal”.

Intensive Search

The next stage of the hotel journey is where the similarity between Indian travelers’ behaviors and those associated with bazaars become strikingly apparent. Having narrowed down their selection to a small number of options, again and again we saw travelers using a range of means to verify online information and glean additional information.

Not trusting the information on a single platform, travelers often check the same hotel across multiple platforms. Many seek verification from hotels directly, typically phoning to ask questions and request photos or videos. Hoteliers expect and support these behaviors: travelers “want to know what the hotel looks like and make sure that it looks like what is claimed online”, explained one hotelier in Shimla. “They also want to verify amenities. We often send through WhatsApp.” Here we see the principle of “thorough examination and consultation” (Uchendu 1967, 41) in action.

Perhaps most surprising to any readers accustomed to booking accommodation online in advance, we found it was common to wait to inspect a hotel in person before committing. 32-year-old Sita travels with her husband and young daughter. She tends to book two or three hotels in advance via OTAs, then visits each option in person before making a final decision, noting that “we like to check out the rooms and see what other amenities they have for kids, make sure our daughter will be comfortable there”. The desire of Indian travelers to “wait and see” drives a preference for apps with flexible reservation policies. One traveler remarked that the disadvantage of Airbnb is that you have to pay upfront, and you do not even know the exact location of the property until you book.

Meta Search

The act of engaging in intensive search offline—using voice and video calls or WhatsApp messages—begets the information being sought. However, it also enables people to make a judgment about more ineffable factors which matter to them. One participant recounted asking a hotel to send up-to-date photos of rooms over WhatsApp. Beyond assessing the photos shared, she judged the response time: “only if they reply in the next 5–10 mins I go forward with them”. The speed of response was taken as an important signal of the level of service one might expect to receive as a guest at the hotel. Travelers, therefore, willingly seek out interactions with hotel staff (and in some cases, other hotel guests) to garner this kind of second order information.

In India, meta search is an important component of hotel room booking decisions and a key causal factor in the prevalence of on- and offline booking behaviors. If extensive search helps with assessing the hotel landscape, and intensive search with the discovery of more fine-grained qualities and characteristics, meta search enables the elicitation of information that can make the difference between a satisfactory and excellent stay.

Multidimensional Haggling

It is pertinent to note that we did indeed see examples of haggling over price. Desire to engage in haggling, rather than accept fixed prices displayed online, drove some travelers like Sakshi to pick up the phone or visit the front desk: “in order to get the best deals I currently call the hotels and negotiate directly with them”.

However, more frequently we observed haggling for extras and flexibilities. When traveling as a group of six, Deepan and his cousins try to fit in two rooms to save money—he calls up the hotel to request this. “Otherwise, we need to shell out on an extra room. They don’t say online, it’s always a secret, you need to call them to ask. If the manager is kind, he says yes.” Ability to negotiate extras was a common reason cited for waiting to pay in person. As another participant, Jiya, noted, “the check in-out time is fixed if you book online but if you go there, you can convince them to move around the timing”. Hoteliers are willing counterparts in these exchanges. “People like to get a package with breakfast included. Sometimes we give them breakfast plus one more meal”, a hotel manager in Rishikesh explained.

We see, then, a clear pattern of eschewing the path of least resistance (searching, selecting and booking a hotel online in advance of a trip) for one involving considerable time, effort and human interaction.

These stories are supported by available market data. In 2020, according to a leading travel industry research group, only 5% of bookings were made online directly with the hotel and 30% through OTAs, with 65% made offline, either in-person or over the phone (Phocuswright 2020). The pre-Covid numbers for 2018 and 2019 were 72% and 69% respectively (Phocuswright 2020).

2.3 The Online Puzzle

At first glance the online world might be seen as the purest expression of the rational market where plentiful information instructs transactions between disinterested, remote parties, and leads to perfect price optimization.

The Indian hotel market, then, represents something of a puzzle. It operates in what is technologically an extremely sophisticated market. Those with the means to travel and book hotels have smartphones and the apps required to discover, research and book hotels but, in general, they disavow the invitation to complete the transaction in the frictionless ways available to them. Despite the apparent abundance of information online via OTAs, hotel websites, social media accounts and travel bloggers, industry data and our own ethnographic explorations make it clear that on- and offline behaviors comfortably coexist.

It is not a market qua market—one in which the logics of “pure” economic exchange dominate—but one in which practices more commonly associated with the bazaar are in evidence. It is a market that combines elements of the online world and practices more commonly associated with the offline world: dense interaction, communication, assurance-seeking and deal striking.

The question remains: why? And how might an understanding of bazaar behaviors inform our understanding of the online world in a broader set of market contexts? To answer these questions, it is necessary to explore in more detail the qualities that hotel (and rooms) exhibit as commodities, and the cultural and economic logics in play.

SECTION 3. MAKING SENSE OF BAZAAR BEHAVIORS

3.1 The Qualities of Hotel Rooms as Commodities

One place to start making sense of the persistence of bazaar behaviors in an ostensibly online market is to explore the nature of hotel rooms as commodities. As we have shown, behaviors such as protracted investigation and bargaining are found cross-culturally for goods with a high-ticket price, or which are infrequently purchased. So, a partial explanation to the enduring appeal of specific economic exchange behaviors is likely to be found in the nature of the commodities in question. Hotel rooms have four characteristics relevant to this analysis.

They are perishable: a room not sold for a night will never yield a profit for the hotel. As a result, sellers are keen to sell, and buyers are aware that hotels have little incentive to have unoccupied rooms. Both parties therefore know that deals can, and should, be struck.

They are heterogenous: hotels are highly variable in quality, location, price, amenities and style. Both across and within hotels, two rooms are rarely, if ever, identical. The nature of the Indian hotel market further amplifies this lack of standardization. There is a very high proportion of independent and small (or lone) operator properties compared to soft-branded7 or chain hotels. Independent and unbranded hotels constitute 72% of the market, branded and traditional hotel chains (domestic and international) just 5%, and conversion branded hotels (for example those listed on OYO) and “new-age chains” (Ginger, Lemontree) run to 8% (Hotelivate 2019). This structure amplifies what is, by its very nature, a highly heterogeneous market. One reliable proxy—brand-led standardization—is largely absent, particularly away from the top end of the market.8 Gaining a nuanced picture of the specific hotel and room under consideration through rigorous information gathering is therefore the main way to ensure expectations are met.

They are hard to evaluate: without in-the-flesh inspection rooms are hard to assess with any degree of certainty. Pictures, videos and reviews as sources of information go only so far in helping Indian travelers discriminate and make choices. “It’s misleading”, bemoaned one participant. “Sometimes the bedsheets are not proper, there are bugs, it’s way too small…you can only understand a certain extent from a picture. When you get there, you really understand how it looks, how it smells, how clean it is, there is an AC but does it actually work?” Noise, smell, cleanliness and sense of safety are crucial criteria which travelers struggle to discern from online information alone; on-the-spot evaluation is preferable. Moreover, as an experiential commodity reliant on service and hospitality, “performance is always different and cannot be tried or tested before purchase” (Fernández-Barcala 2010, 2)—for this reason would-be guests look for signals that might help predict their experience, such as staff demeanor over the phone.

They are high stakes: trips are, for most, a break from daily life. They are keenly anticipated and deeply valued. This is particularly true for the millions of Indian citizens who are entering the travel market for the first time in recent years with aspirations fueled, in no small part, by inspirational content on social media, together with the government’s domestic tourism campaigns mentioned earlier. In addition, large family trips, which are very common in India, place a huge amount of pressure on the organizer to ensure that the chosen accommodation meets the often-exacting standards of older relatives. As 25-year-old Asha expressed, “I need to carefully plan everything when traveling with my parents because if something goes wrong, they would blame everything on me”. Therefore, finding the right hotel, and getting the best deal, justify a considerable investment of time and effort.

Igor Koptytoff (1986) describes the way that objects oscillate between commodity and “singularity”, between being homogenous, and being singular objects with a unique value. Extensive and intensive search, negotiation and bargaining signal the desire of hotel bookers to “singularize” their purchase: to transform the homogenous or mass into something special or unique. In the context of a market with an emerging middle class with disposable income this transformation from commodity to singularity brings to mind Alfred Gell’s comment on “newcomers to the world of goods”:

“[W]e should also recognize the presence of a certain cultural vitality in these bold forays into new and untried fields of consumption: the ability to transcend the merely utilitarian aspect of consumption goods so that they become something more like works of art, charged with personal expression.”

(Gell 1986, 114)

In-depth discussion about a hotel room with a hotel manager prior to booking clearly does not make the room into a work of art, but it does charge it with significance. In that light, there is a certain logic in opting for more, not less friction.

Significantly, the characteristics we have outlined for the hotel market are similar to many of the commodities sold in a typical bazaar: unbranded, highly heterogeneous, of unknown provenance and consequential value, and therefore deserving of deeper investigation. Hotel rooms and goods in the bazaar share an equivalence: what exactly they are needs to be revealed before people can happily finalize their transaction.

3.2 The Cultural Logics of Hotel Search in India

Neither commodities, nor the modes of economic exchange that they are enmeshed in, exist in a vacuum. It is important to understand the cultural context and logics that prevail. Our research highlights some broad cultural dynamics at play that shape people’s behavior when making hotel reservations: bargaining as a social norm, value maximization mindset, low trust in exchange partners and cultural plurality.

Bargaining as a social norm: the acceptability, or desirability, of engaging in bargaining varies by culture. For as Geertz observed, “[b]argaining does not operate in purely pragmatic, utilitarian terms, but is hedged in by deeply felt rules of etiquette, tradition, and moral expectation” (1979, 105). This runs in both directions. Gretchen Herrmann’s work on garage sales in the USA shows how some sales participants disguise themselves before engaging in bargaining activities, such is their discomfort with the practice. Meanwhile others, such as Eastern European, Indian and Chinese participants, be they buyers or sellers, are more comfortable and even proud of publicly displaying their negotiating skills (2003, 239). So, while Herrmann noted “Americans’ general ambivalences towards bargaining and the premium they place on friendly day-to-day economic interactions” (2003, 241), in the context of India bargaining is widely practiced, highly valorized, and something that people are keen to demonstrate their skills in. Indeed, there is “social prestige and honor” (Uchendu 1967, 45) attached to both the performance, and results, of bargaining.

Value maximization mindset: a mindset which Indians refer to as paisa vasool (literally money recovered, more idiomatically “getting the best bang for your buck”) leads to value hunting behaviors. But paisa vasool extends beyond merely saving money to maximizing the value of interactions, transactions and experiences. Extracting extras from a hotel—an additional bed in a room for a child, late check out, or full board for the price of half board—are all evident when people engage in bazaar-like interactions with hotel management. Extracting this value is often easier through direct communication, providing a compelling reason not to book online.

Low trust in exchange partners: generalized suspicion about the intentions of individuals and businesses outside of one’s circle of known associates leads to assurance-seeking behaviors. This default lack of trust in the information given about products and services was captured by one Varanasi resident who told us, “we make our own milk or buy from friends. You can’t trust the milkman, he’ll water it down.” In the context of travel, people are skeptical about the claims made by hotels, especially online. For example, many participants expressed the suspicion that photos on hotel websites were likely outdated and misleading.

High cultural plurality: the extensive religious, regional and cultural diversity of India leads to preference-specifying behaviors. People from different communities have specific requirements that need to be accommodated. Participant Siya is from the state of Gujarat and only wants to stay in hotels that cater to her regional dietary preferences: “someone we know told us that the hotel serves Gujarati food and all our food requests would get fulfilled. Hence we called them to confirm and then booked.” In a context where specific dietary needs are more than mere preferences, and often involve prescriptions and proscriptions, verifying that they can be catered for is crucial. Double checking on the phone is preferable to leaving things to chance.

Our analysis thus far has explored the commodity qualities and cultural logics shaping behaviors in the India hotel market. We have argued that bazaar behaviors involve the combination of extensive, intensive and meta search to assess the qualities, and ultimately agree on the price of hotel rooms, which have a series of qualities that make them more or less unknowable, whatever the information available about them online. These different forms of search—engaged in both on- and offline—occur in a cultural context in which the goal of value maximization is all important and where people do not always take the information presented to them at face value. Bazaar behaviors also help would-be hotel guests ensure that their religious, caste or community preferences, prescriptions or proscriptions will be catered for.

Given that determining the price of a commodity is the logical endpoint of the different forms of informational search that we have outlined, and haggling is seen as the signature practice of the bazaar, the economic dimension of hotel search and booking demands further explanation—not least because in online marketplace where prices are clearly articulated it might be assumed that bargaining is unwarranted.

3.3 The Price Information Context

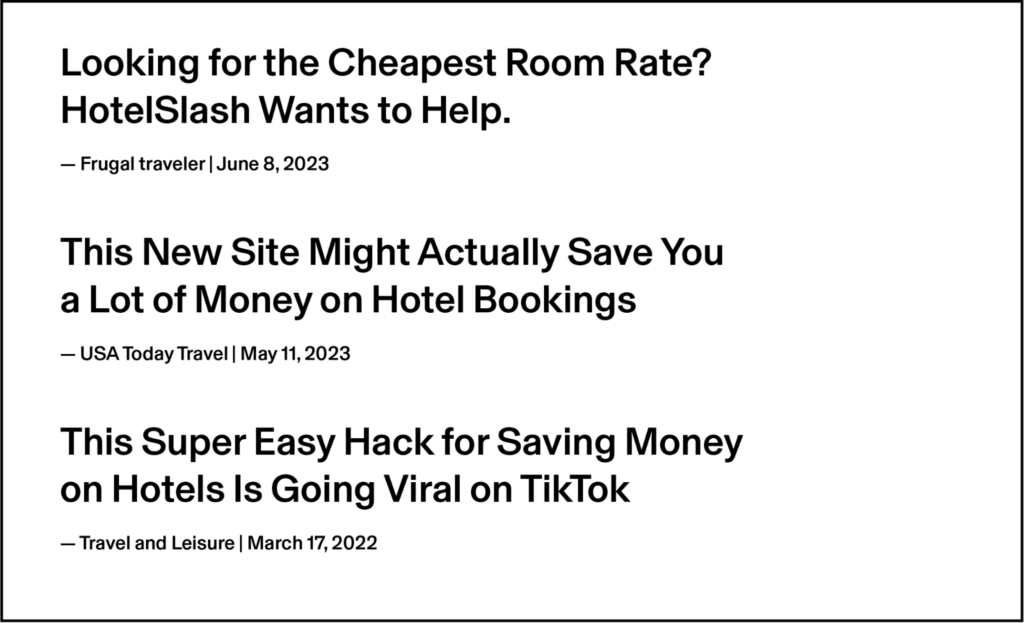

Let us return to Geertz’s description of the information landscape: “in the bazaar information is poor, scarce, maldistributed, inefficiently communicated, and intensely valued” (1978, 29). One might argue that online information pertaining to hotels and their rates is in contrast: rich, plentiful, instantaneously accessible, efficiently communicated, and freely available to all. However, there are three features of the present-day online hotel market (as experienced in India, but also internationally) which lead it to in fact more closely match Geertz’s description.

Price information overload: for every destination, there are multiple hotels; for every hotel there are multiple room options; for every hotel and room option, there are different prices available via different booking sites, and each room-hotel-booking site combination may be advertised across multiple aggregator sites, each of which may offer additional deals or rewards. The sheer volume of permutations leads to an inflection point when signal becomes noise—when information plenitude is experienced as information anxiety.

Prices are in flux: first popularized for flight booking, hotels are increasingly adopting dynamic pricing, where instead of fixed rates for certain dates, room prices fluctuate in response to demand. Such algorithmically determined prices are unstable, variable, and not necessarily the same for everyone. Moreover, scarcity tactics (eg., “only one room left at this price!”) may be used to inflate demand, sometimes artificially. Travelers cannot trust that the price they see on a given day is reasonable or universal.Prices are deliberately opaque: hotel booking platforms are increasingly following the practice of drip pricing whereby common components of a service are unbundled from the upfront offer and reintroduced at a later stage in the booking process as “extras”, for an additional cost. Other platforms hide compulsory fees and taxes until the final stage of booking, artificially lowering their sticker price to undercut competitors during the initial search phase. Writing for The New York Times in June 2023, Brian X. Chen remarks:

“[T]he days of using search engines like Google, Expedia and others to rapidly search for travel deals are long gone. You might be able to get an idea of the approximate cost of a ticket or hotel room, but you have to put in a lot more time and effort to tally up the real cost.”

These practices force the traveler to run through the different permutations of what different websites are offering, to compare the often incommensurate, before making a decision. Here, we hear echoes of Geertz’s concept of multidimensionality, where “quantity and/or quality may be manipulated […] In a system where little is packaged or regulated, and everything is approximative, the possibilities for bargaining along non-monetary dimensions are enormous”

(1978, 31).

Combined, these features create a chaotic user experience. Search results often beget more questions than they answer: why is there such variability? Is what I am getting for price X different than if I pay price Y? What risks are there in opting for a cheaper price? The market is allegedly acting as it meant to but creates instability and uncertainty. The net result is a distinct sense of distrust in price information displayed online, and a series of questions which extend far beyond prices and which cannot be satisfactorily answered without further, often offline, research.

In a piece for The Atlantic published in May 2023, “Hotel Booking is a Post-Truth Nightmare”, Jacob Stern details the unscrupulous practices used by hotel booking sites and aggregators and the effect on consumers:

“Buying stuff online is often stressful, but booking a hotel these days is a uniquely excruciating experience. […] The best analogy for online hotel booking, I think, is a hall of mirrors: You can’t tell what’s real, and you can’t escape.”

A cottage industry of hotel price hacking advice has emerged in response and acts as further evidence of the informational maelstrom travelers find themselves in when looking for a place to stay.

Here we see a further challenge to the implied teleology of bazaar to market. The technological advancement of hotel search and booking has created a system which is decidedly and increasingly bazaar-like. Bazaar behaviors in this context make sense. The Indian hotel booker is smart in not assuming that the information they are presented with is complete, trustworthy or objective, and in undertaking additional steps to ensure an acceptable lodging choice.

SECTION 4. FROM THE PARTICULAR TO THE GENERAL: THE BAZAAR AND ONLINE COMMERCE

4.1 Generalizing Bazaar Behaviors

In this final section, we consider how an account focused on the booking of hotel rooms in India might be legitimately generalized to other market verticals and contexts. Our aim is to explore the extent to which bazaar behaviors provide a useful lens for understanding online marketplaces not just in “emerging” or “frontier” markets, but in Western or other developed economies. As we noted at the outset, orthodox economic theory has implied that the sort of behaviors we have given an account of should wither away in favor of more frictionless transactions. And yet, as we have demonstrated, they do not because they make sense for certain commodities transacted in certain cultural and informational contexts. At this juncture it is worth restating that bazaar behaviors have never been a phenomenon only seen in non-Western contexts.

Our aim then is less to provide a predictive model but rather a framework that suggests under what circumstances people might favor friction rather than seek to expunge it from their online transactions. Our hope is that by offering this corrective to the teleology of “bazaar to market” we can guide the development of online marketplaces that serve both buyer and seller better and allow intermediaries and aggregators the means to design their platforms in such a way that friction is recognized as a positive virtue, not something to be designed out.

To do that, we return to the three key factors that our analysis has shown to be relevant to bazaar behaviors: the qualities of commodities, cultural logics, and price information context. We provide a set of questions within this framework that might usefully guide those creating online marketplaces, or acting as market intermediaries, where bazaar behaviors are likely to be a reality.

Commodity Qualities

As our account has shown, the qualities of commodities have an important bearing on how exchange plays out. Commodities with certain qualities lend them a propensity to be subject to bazaar behaviors.

Perishability: we showed that hotel rooms are perishable. Many other commodities are perishable, such as fresh food, theater tickets or airline seats—if they remain unsold, they go bad or remain unused. Perishability creates an urgency on the part of the seller, and the opportunity for the buyer to get themselves a bargain. A temporal dimension is at play that impacts the perceived or actual value of the commodity. Perishability of a different sort is also a dimension for goods of a non-perishable nature. A seller may wish to shift everything towards the end of a period (say a fashion season or sale day) rather than find themselves with unsold stock and all its associated costs.

- How perishable are the goods being sold?

- Are they perishable by their nature or is their perishability created through temporal or other interventions?

Heterogeneity: the extent to which a commodity is standardized is widely acknowledged to have a bearing on exchange practices: “the greater the variation in the quality and quantity of a unit of commodity, the more haggling there seems to be” (Uchendu 1967, 37). It follows that online marketplaces for unstandardized products need to take seriously the importance which buyers and sellers will attach to some back and forth on the nature, and the value, of the goods being sold.

- To what extent are the commodities on sale standardized?

- What differences between apparently similar commodities might need to be highlighted?

Evaluability: highly related to the question of standardization is the extent to which a product can be evaluated. Those which are harder to evaluate will require more intensive information and ultimately price search.

- What information might be expected to be sought about a commodity?

- What explicit or more implicit information might be valuable to a buyer, and how might sellers seek to represent or provide commentary on it?

Consequentiality: routine purchases of groceries or other standardized goods of low value are generally considered not worth the time cost of extensive and intensive search. On the other hand, high value items, and those less frequently purchased can be deemed worth it. The value of items is not fixed: in times of inflation or scarcity, or for certain consumers in certain contexts, even humdrum commodities are worth the time cost involved in driving a better deal.

- What is the cost of the item in the context of wider purchasing power or average income levels?

- What is the frequency of purchase?

- What other factors are in play that make a commodity high stakes to an individual or at a wider cultural level?

Cultural Logics

As economic anthropology has shown, cultural and moral logics are at play in almost all exchange activity. Our account has focused on those governing exchange, on- and offline, in India, and we have argued that it is not possible to understand how “business gets done” without referencing them. The existence of similar logics in other cultural settings cannot be assumed, but our analysis suggests paying attention to certain dimensions that influence the likelihood of bazaar behaviors and may make them worth designing for rather than designing out.

Social norms around bargaining:

- Is the “art of the deal” important on both sides of an exchange relationship?

- Is bargaining seen as an integral and valued part of exchange in a particular setting? Is it the expectation rather than the exception?

- Are exchange skills prized as a source of prestige?

Mental models of value:

- What are the cultural concepts of value in play?

- To what extent is value claiming and seeking established as a cultural expectation of both buyer and seller?

Trust in transactions:

- What assumptions do buyers and sellers make about each other’s intentions?

- To what extent is information about commodities taken at face value?

- How does background cultural noise about scams, malfeasance and fraud influence how people conceive of exchange?

Cultural plurality:

- To what extent is the market culturally plural?

- How does this affect buyers’ diversity of requirements for the commodity in question?

Price Information

We have challenged the idea that fixed price online marketplaces eliminate the information asymmetries commonly associated with the bazaar. Our analysis shows that it is not in spite of but in part because of information plenitude that bazaar behaviors persist in online markets. Technologically advanced features like dynamic pricing generate further confusion and uncertainty. In this context, additional offline investigation is often prudent.

Volume of price information:

- How vast is the set of price options online?

- To what extent are buyers able to confirm they’ve found the best price for a given product or service?

Stability of price information:

- Is pricing fixed or dynamic?

- How do buyers understand price fluctuations?

Transparency of price information:

- Are prices clear and transparent?

- To what extent is it possible to compare and contrast similar options online without thorough investigation?

4.2 Concluding Thoughts

At the outset we argued that the distinction between the market and bazaar is at best false, and at worst unhelpful since it effaces the ways in which the ideology of the market fails to capture the multitude of ways in which economic exchange is shot through with social relations and moral values.

We end with the proposal that it might have some analytical merits after all. In the specific case of the hotel market in India, it has provided a way to see how the market really operates and why it works the way it does. And while one of our aims has been to introduce some friction into the idea that bazaars are “less than proper” markets hanging around in what Chakrabarty termed the “waiting room of history” (2000, 7), the other has been to show that bazaar behaviors, far from being exotic performances—mere affectations—are in fact highly rational ways for market participants to operate. Indeed, it is worth observing that many of the breakout successes in the age of platform capitalism (eg. eBay and Airbnb) are sites which explicitly embrace bazaar behaviors.

In the tradition of anthropological analysis, we have explored a particular socio-cultural and economic phenomenon to reframe and make sense of it. However, we believe that our analysis has more general applicability to scholars and practitioners seeking to understand or build arenas of economic activity which are optimized for all market participants. Our final contention is that bazaar behaviors should not be designed out, nor merely tolerated, but embraced as indications of economic activity at its most engaged, vital and meaningful.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Simon Roberts is an anthropologist, founder of Stripe Partners and Board President of EPIC People. His doctorate explored the satellite television revolution in north India in the mid 1990s. He is the author of The Power of Not Thinking: How Our Bodies Learn and Why We Should Trust Them (Heligo Books 2020). simon.roberts@stripepartners.com

Erin Hackett is a researcher and strategist, and Associate Director at Stripe Partners. She specializes in foundational research, using ethnography to make sense of emerging technologies. She holds an MA in Anthropology from the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, and a BA in Human Sciences from the University of Oxford. erin.hackett@stripepartners.com

Sohit Karol leads the UX Research team for Real World Journeys on Google Search in the international markets. His team draws from diverse disciplines like Anthropology, Behavior Science, Human Factors, Linguistics, Applied Neuroscience and Machine Learning to enable a human centered approach to product lead growth.

Diego Baron leads Product Management for Google Search: Place Journeys Growth with a team focused on Search, Innovation and Growth. He applies a combination of Behavioral Science, Strategic Analysis and Machine Learning to create new product and business growth opportunities. He holds a JD from Harvard Law School and a BSE in Computer Engineering from the University of Michigan. diegobaron@gmail.com

NOTES

Every piece of writing is a team effort, especially when it derives from a significant piece of fieldwork. Our thanks to Stripe Partners colleagues: Jacobo Medina for his work on the original project and with design, and Cath Richardson and Danish Mishra for close readings of the paper. In India, Zubin Pastakia and Divya Viswanathan at Tropic Design, and Swar Raisinghani and Nikhita Ghugari at Xeno Co Lab contributed significantly to our understanding of the market context. Many Googlers helped push our thinking in the field, and subsequently. Page Ive laid important foundations for the study and was a key collaborator during fieldwork and beyond. Special thanks to Karl Mendoca (Google) for his engaged and supportive curation. We would also like to acknowledge the support and incisive comments of Julie Farago, and the late Andrew Silverman, the executive sponsors of the project that gave rise to this paper.

1. In this paper we use the term haggling and bargaining interchangeably.

2. For further elaboration of the historical and historiographical scholarship exploring the market nature of bazaars in colonial India see Ray (1995) and Bayley (1983).

3. This distinction between two types of trade was an important dimension of the “civilizing” mission of colonialism. Accounts counterposing two modes of economic exchange became central to a colonial ideology that equated different types of trade with different types of society. Gemeinschaft—a society where economic activities are based on formalized and impersonal social relations, was contrasted to gesellschaft—a society where community and social relations pattern exchanges (eg. Sarkar 2022).

4. It is worth noting that the emergence of fixed price exchange enabled social distinctions to be made within the West. Alexander Stewart is credited with introducing fixed and visible prices in his New York dry goods store in 1823, and this innovation diffused to eventually dominate the retail sector. Packaged goods with trade names (proto-brands) became positioned as more sanitary and of better quality than unpackaged goods. Class distinctions became etched into the opposition between such branded goods and the stores that sold them, and their unpackaged counterparts sold without a fixed price in less “savory” locations (eg. Herrmann 2003, 238). The distinction between two types of economic exchange within the USA added further freight to the idea that bargaining was less advanced than fixed price exchange.

5. The idea of “alternative modernities” is relevant here, challenging the assumption of linear development and arguing that modernity always “unfolds within specific cultures or civilizations and that different starting points of the transition to modernity lead to different outcomes” (Gaonkar 1999, 15).

6. For a detailed history see J.P. Singh’s “Leapfrogging development?: the political economy of telecommunications restructuring” (1999).

7. Soft-branded is a term used in hospitality that describes a hotel franchise or chain company. This organization, in comparison to other hotel franchises or hotel chains, provides the benefits of a larger chain without enforcing strict rules, regulations or strong brand identity on the franchisor or chain member (Xotels n.d.).

8. A fuller portrait of the Indian hotel market can be found in Chitra Narayanan’s “From Oberoi to Oyo: Behind the scenes with the movers and shakers of India’s hotel industry” (2022).

REFERENCES CITED

Aiyar, Shankkar. 2017. Aadhaar: a biometric history of India’s 12-digit revolution. Chennai: Westland Publications Ltd.

Akerlof, George A. 1970. “The market for ‘lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 84, no. 3 (Aug): 488–500. https://doi.org/10.2307/1879431

Alexander, Jennifer, and Paul Alexander. 1987. “Striking a Bargain in Javanese Markets.” Man 22, no. 1 (Mar): 42–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/2802963

Alexander, Paul. 1992. “What’s in a Price? Trading Practices in Peasant (and other) Markets.” In Contesting Markets: Analyses of Ideology, Discourse and Practice, edited by Roy Dilley, 79–98. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Bayly, Christopher. 1983. Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion 1770-1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cable. n.d. “Worldwide mobile data pricing: The cost of 1GB of mobile data in 237 countries.” Accessed September 23 2023. https://www.cable.co.uk/mobiles/worldwide-data-pricing/#resources

Carrier, James G., ed. 1992. A Handbook of Economic Anthropology. Cheltenham and Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Carrière-Swallow, Yan, Vikram Haksar and Manasa Patnam. 2021. “India’s Approach to Open Banking: Some Implications for Financial Inclusion.” IMF Working Papers 2021, no. 52. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513570686.001

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (New Edition). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Chen, Brian X. 2023. “Watch Out for ‘Junk’ Fees When Booking Travel Online.” The New York Times, June 15, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/15/technology/personaltech/travel-booking-junk-fees-html

Deka, Maitrayee, and Adam Arvidsson. 2022. “Names doing rounds: On brands in the bazaar economy.” Journal of Consumer Culture 22, no. 2: 495–514.

Fernández-Barcala, Marta, Manuel González-Díaz, and Juan Prieto-Rodriguez. 2010. “Hotel quality appraisal on the Internet: a market for lemons?” Tourism Economics 16, no. 2: 345–360.

Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar. 1999. “On Alternative Modernities.” Public Culture 11, no. 1: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-11-1-1

Geertz, Clifford. 1978. “The Bazaar Economy: Information and Search in Peasant Marketing.” The American Economic Review 68, no. 2: 28–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1816656

Geertz, Clifford. Originally published 1979. “Sūq: the bazaar economy in Sefrou.” In Sūq: Geertz on the Market, edited and introduced by Lawrence Rosen. Chicago: Hau Books, 2022.

Gell, Alfred. 1986. “The Muria Gonds: Newcomers to the world of goods.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 110–138. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

GSMA. 2021. “The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity 2021.” Accessed September 23, 2023. https://www.gsma.com/r/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/The-State-of-Mobile-Internet-Connectivity-Report-2021.pdf.

Herrmann, Gretchen M. 2003. “Negotiating culture: Conflict and Consensus in US Garage-Sale Bargaining.” Ethnology 42, no. 3 (Summer): 237-252.

Hotelivate. 2019. “The Ultimate Indian Travel Report Vol 1.” Accessed September 23, 2023. https://hotelivate.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-Ultimate-Indian-Travel-Hospitality-Report-Vol.1-2019.pdf

Kopytoff, Igor. 1986. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in cultural perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64–92. Cambridge University Press.

Khuri, Fuad I. 1968. “The Etiquette of Bargaining in the Middle East.” American Anthropologist 70, no. 4: 698-706.

Miller, Daniel. 1998. A Theory of Shopping. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Morgan Stanley. 2022. “India’s Impending Economic Boom.” Accessed September 23, 2023. https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/investment-opportunities-in-india

Narayanan, Chitra. 2022. From Oberoi to Oyo: Behind the scenes with the movers and shakers of India’s hotel industry. Gurugram: Penguin Random House India.

Phocuswright. 2020. “India Travel Market Update 2020.” Accessed September 23, 2023. https://www.phocuswright.com/Travel-Research/Market-Overview-Sizing/India-Travel-Market-Update-2020

Ray, Rajat K. 1995. “Asian Capital in the Age of European Domination: The Rise of the Bazaar, 1800–1914.” Modern Asian Studies 29, no. 3 (July): 449–554.

Reliance Industries Ltd. 2021. “Media Release January 2021: Q3 (FY 2020-21) Financial and Operational Performance of Reliance Industries Limited (RIL)” Accessed September 23, 2023. https://www.ril.com/getattachment/40353e47-fcf3-4ccf-89ea-b83d1f44eb43/Q3-(FY-2020-21)-Financial-and-Operational-Performa.aspx.

Ruby, Daniel. 2023. “WhatsApp Statistics Of 2023 (Updated Data).” DemandSage, August 11, 2023. https://www.demandsage.com/whatsapp-statistics

Sarkar, Bhaskar. 2022. “Bazaar, The Persistence of the Informal.” In concepts: a travelog, edited by Bernd Herzogenrath. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Sethuraman, Nallur R. and Anisha Ajith. 2023. India govt’s open e-commerce network ONDC expands into mobility.” Reuters, March 23, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-govts-open-e-commerce-network-ondc-expands-into-mobility-2023-03-23/

Singh, J.P., 1999. Leapfrogging development?: the political economy of telecommunications restructuring. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Statista. 2023. “Number of domestic tourist visits in India from 2000 to 2021.” Accessed September 23, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/207012/number-of-domestic-tourist-visits-in-india-since-2000/

Stern, Jacob. 2023, “Hotel Booking is a Post-Truth Nightmare.” The Atlantic, May 1, 2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/05/hotel-booking-sites-junk-fees-travel/673898/

Uchendu, Victor C. 1967. “Some Principles of Haggling in Peasant Markets.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 16, no. 1 (Oct): 37–50.

Wilk, Richard, and Lisa Cligget. 2018. Economies and Cultures: Foundations of Economic Anthropology. 2nd ed. Abingdon-on-Thames, Routledge.

Williams, Raymond. 1990. Problems in Materialism and Culture. London: Verso.

Xotels. n.d. “Hotel Soft Brand.” Accessed October 2, 2023. https://www.xotels.com/en/glossary/soft-brand