Human-Centered Innovation has come to be known as the central discipline in the entrepreneurial arena. Through three-years of directorship at Innovation Studio Fukuoka, a “citizen-led” innovation incubation platform in Japan, multiple approaches have been investigated and thus learned a successful to-be-entrepreneur him/herself has to co-own a concern with potential customers that evokes him/her a mission to pursue, that is beyond simply understanding customers with empathy. We witnessed ethnographic approach well facilitates the to-be-entrepreneur to meet an unaware yet intrinsic personal concern and nourish to co-own it with the customers. We also discuss what and how ethnographic praxis in industry can contribute to the entrepreneurial arena and propose a new role that we experienced ethnographers to take.

“Hmm, what’s the most meaningful stuff I had in the five months?

I learned a lot of things here,

But, dare to say, Oka was always there for me.He helped me a lot especially when I reflect on myself.

When I was losing the way and when I was dithering…”—Hiro, an alumnus of Innovation Studio Fukuoka, 2015.

WHEN ETHNOGRAPHY ENCOUNTERS STARTUP-ARENA

In the past decade, the corporate arena has come to know that ethnography is an effective tool, bringing customer insights and help create essential values as they were sophisticatedly woven them into the process of product and service creation in a human-centered manner. This recognition, which originally started off from large multinational organizations where understanding another distant culture is naturally crucial, is now known and considered essential even to early and small teams such as startups (Aulet, 2013).

One of the primary attractions among the startups that ethnography or the ethnographic research seem to entail is its power to bring empathy, the ability to “reach outside of ourselves and connect with other people (Patnaik and Mortensen, 2009)”. Today major startup incubators and accelerators emphasize the significance of hiring ethnographic researchers or the team to adapt such set of skills in order to help them access customer insights. This corresponds to the trend of startups where the significance and the viability of human-centric approach is recognized over technology-centric ones (Kolko, 2014).

While corporate ethnographic praxis has been the primary profession for the authors of this paper, the trend today has led us to take an initiative in innovation lab. Since 2013, authors of this paper have established an innovation incubation platform named Innovation Studio Fukuoka based on the request by the city and its directive council of Fukuoka, a capital of southwest Japan with 1.5 million in population. The program is a series of five -months incubation programs, each of which addresses different societal challenges such as health, social boundaries, and ageing. In each program, approximately 60 individuals comprised of primarily citizens and some employees selected from the sponsored companies of the program would participate, forming ten to fifteen teams to become entrepreneurs or intrapreneurs based on the product and service ideas they eventually conceive. The participants so far range widely from technologists, designers, educators, social workers, housewives, and even to high school and college students.

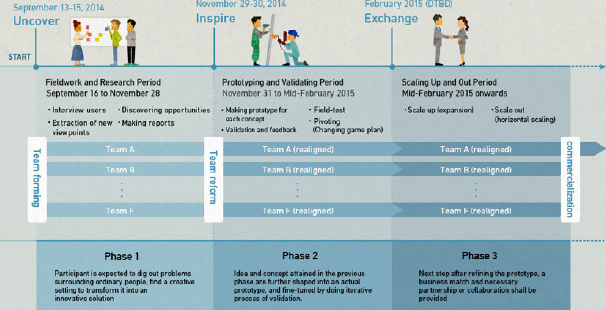

Figure 1. Process of the second project of Innovation Studio Fukuoka “Designing Sports in Everyday Lives.” It was five-months long began in September 2014 and ended February 2015. See details at http://innovation-studio.jp/en/project/index.html © Fukuoka Directive Council, used with permission.

The characteristics of this program is although most participants have never been involved in a human-centered design practice, participants would start from research, spending substantial amount of time. At the very beginning teams are asked to define their field of interest, refine research questions, and conduct interviews and participatory observations. The program also takes into account that as a result of research, participants may rewrite their interest and areas to work on, and allow them to reorganize or even set up new teams. The second half of the program will take these unfolded insights, where teams will ideate new business concepts and prototype them. Towards the end, the participants will pitch their business concepts to venture capitalists, public sponsors, government policy makers and social impact bonds that would support the conceived business concepts to happen. Since the fall of 2013, Innovation Studio has organized four programs, one of which is ongoing as we write this paper. The program has so far had over 30 teams with approximately 100 participants to reach the final gate, among which 14 teams have started or are about to start their own businesses based on the outcomes of the program.

Quite a few lessons learned through the past programs. First, we were once again struck by the power of ethnographic research: Despite being their first to conduct research, participants delivered great stories and insights based on the research they have conducted, and were capable to inspire not only themselves but also the other participants and even mentors of the program. Secondly, we saw the power of empathy, as it enabled teams to gain deep understanding on their potential customers that eventually became the source of ideas.

However, what intrigued us the most took place in the second half of the program, when business ideas were generated and prototypes were made: we saw some teams fall behind despite of attractive business concepts based on their research outcomes. As we carefully observed and listened to each team during and after the program, we have come to notice that tenacious teams had all acquired new lens to see what potential customers to be concerned about, and as a result, were able to conceive ideas that not only addressed the concerns of potential customers, but also, addressed some of their own. In other words, we saw the concern was shared and what we call as co-owned (Uchida, Ichikawa and Tamura, 2014). The result was a better idea with a bigger impact, enabling the team members and even potential customers, who were involved in their repeated interventions to the field mainly as ‘informants’ to the first half and as ‘reviewers’ to the second half, to wish for its fruitful success. This sense of co-ownership was a much more powerful outcome of their research activities than empathy that usually is understood to perceive the other person as if one were him/her but without ever losing the ‘as ifs.’ (Rogers, 1966).

In this paper, we expound how this generative phenomenon happen and discuss how it works when one would become an innovative entrepreneur through research.

SENSE OF CO-OWNERSHIP: HOW SOME TEAMS CREATED BREAKTHROUGH STARTUPS AND DID NOT

Fukuoka, located in the Southwest of Japan, is the administrative, economic, and transportation center of Kyushu. It is the largest city in the region and belongs to the fourth largest metropolitan area in Japan. Being distant from the Japan’s national government while being closer to other Asian cities across the sea, the city has a culture of autonomy and grassroots efforts, which makes its citizens highly in sync with the notion of citizen-led innovation of the Innovation Studio program. Fukuoka almost always shows the highest rate of inauguration among the large cities in Japan.

In recent years, entrepreneurship has been the central interest of the local government that is strongly driven by the mayor Soichiro Takashima known as a leader of the oncoming generation in Japan’s political arena. Innovation Studio Fukuoka, the innovation incubation platform, lies at the heart of its policy. Since the authors of this paper were named as directors of the studio in 2013, a constant effort, and in some cases, an appeal has been made in order to keep the effort suited for Fukuoka, where it is primarily ‘citizen-led’ that distinguishes itself from the rest of the nation’s ‘large capital-based’ or ‘top-down.’ Organizers have also been careful that the studio avoids participants to be technology-centric: upon the announcement of each program when we receive applications from potential participants to make sure there are themes are announced to appeal the program’s emphasis on the human side of the innovation. So far four programs addressed following themes: “Reconstructing the social boundaries between kids with special needs and without”, “Designing sports in everyday lives”, “Innovating the life course: future of human network, career and growing up”, and “Discovering hidden resource: people and materials.”

Although the studio currently runs its fourth program, its learning and reflection are still in progress as we speak. However, here we take one of the previous programs called “Designing sports in everyday lives” as an example and describe how three teams has succeeded and failed in shaping their businesses.

Team A: Led By Hiro

Hiro was in early thirties, a father of two daughters who were age two and zero respectively when he was at the project. He earned his PhD in material science and worked as a freelance consultant for local businesses and schools. In the first half of the session, he was not really a lead of the team. The team encountered a variety of informants under the hypothesis that parents often desire their kids to work out what they could not. However, the very change took place for Hiro and his team members when the team visited a family, or, to be more specific, a father and a son. When the father was a child, he dreamt to become a baseball player but he could not for family reasons; As he had a son, he again dreamt that his son would become the one, in particular, eventually to play at Koshien Stadium, where the final national high school baseball tournament is held. He has started to train his son when his son was a baby, prepared the best environments for his son to practice including choosing a team led by a quite a coach and devising a way to review every play in a game using camcorders and other instruments to measure his son’s performance. Other than baseball itself, he studied nutrition and physical therapy for his son to build up his strength. As the result, his son successfully joined a leading senior high school team, gained a regular position and won out local preliminary games, and finally got hold of the right to come in the tournament at Koshien! This is truly a successful case of nurturing and seemed perfectly holding true to the hypothesis that the team conceived, but Hiro had another perspective: “Has he really intended to ‘nurture’ his son?” Because he frequently used the term ‘we’ when he explained how his son having achieved the goal, Hiro realized that over the years, it was not his son who was nurtured, but the father himself: His son becoming a successful baseball player was a goal shared between the two and was realized together as a team! This notion alone gave Hiro a strong inspiration and was enough for him to stop his engagement to the team he joined earlier. He spun out and formed a new team to realize the idea of his own. The idea he conceived is based on a new educational toolkit developed by the perspective: Parent and kid grow together as a team.

In a fast changing era, knowledge is something that quickly becomes obsolete; This especially holds true to digital technologies, therefore Hiro thought it would be essential that the product should be an easily-modified, educational toolkit, which provokes collaborative effort among them. Towards the latter phase of the project, Hiro and his team has developed a prototype and quickly decided to start up a company despite that not a single investor showed an interest in his idea at that moment.

Why is this a case of shaping co-ownership? Because although the opportunity he identified was through the process of studying others, in the end the idea addressed the concern of his own, for being an educator and being a relatively new father of two daughters himself. In other words, his research was no longer a mere inspiration to a new business idea, but was co-owned.

Team B: Led By Yoshi

Yoshi is in mid thirties and had worked for a local company where he built his career in its human resource management. He joined the Innovation Studio program as the company became a sponsor of the program and was appointed as a delegate with an expectation to establish a new venture business of the company. When the program began, he appeared somewhat confused as none of his previous experiences had anything to do with the research-driven innovation process let alone business development. After much struggle, Yoshi joined a team consisted of participants who were interested in pursuing how people shape a health practice. Just like Hiro, Yoshi did not appear to us as the most proactive member of the team.

During the research process, he participated in an everyday community gathering at a cemetery. Consisted of people in their sixties, participants have been practicing radio gymnastics for more than twenty years. Everyday at 6:00 am, participants will quietly come out of their homes, do some exercise, and leave immediately after the radio ends its broadcast without even saying hi to anyone else. The scene appeared bizarre to Yoshi, as he knew that they are acquainted with each other for a long time. Intrigued by the situation, he then continued his study by interviewing the organizer of the gathering how it was organized and who took part. The organizer answered that he was not quite sure who exactly were participating and usually did not do anything together other than the gymnastics.

While the original intention of the team was to identify solutions on how people could construct their everyday health practices, the series of experience evoked him to shift his attention to more immediate, and direct concern of his: The atmosphere of his own company where it seemed to him lacking the direct communication affecting the overall atmosphere of the office. Soon after this shift, he teamed up with engineers in his company and together with scientists in other institutions he started to prototype that can measure different attributes generated during the conversation in a physical space and came up with a new service offering. Eventually he passionately persuaded the management team and succeeded to launch a new business venture inside the company that he has been leading.

After the project, one of the authors of this paper asked him what would he have done if the idea was rejected by the management, and, after a moment’s reflection, he answered that he would have pursued it even if it meant that he needs to leave the company. The transformation that took place inside Yoshi was striking. Just like Hiro, he has become an entrepreneur as he realized that the problem was equally present within his environment rather than in someone else’s. And once he realized that it is solely on his commitment that whether this problem can be solved, he developed a strong sense of ownership. In other words, it was the co-ownership we saw in Yoshi.

While Team A and B describes two successful cases, there is a case of failure where a team halted to continue their pursuit despite of a nifty business idea through their research.

Team C: Led By Iku

Iku is in early thirties and has been working for a branch office of a multinational electronics company where he had been grown as a product developer. He had postgraduate education in information systems that had helped him to create new digital devices in mobility and healthcare businesses. Unlike Yoshi Iku personally applied to Innovation Studio as he has been considering to leave the company and to start a new business on his own. Iku belonged to the same team as Yoshi, and neither was he taking a proactive role. But once he started to conduct his research, he was extremely motivated and drove research forward.

Among the wide range of people he interviewed, the biggest influence came from three elementary school students, who were in fact, not the informants. Three of them and Iku has coincidentally met during the research phase, as he happened to stay at his friend’s villa alongside the beautiful beach. It was a warm autumn day with perfect weather and Iku and his friends planned to bike along the coastline of white sand and green pines. One of his friends brought his kid with a group of friends. They all had taken Nintendo DS with them and as soon as they arrived, they started playing against each other using wireless connection. Disappointed at the scene, Iku urged them to play outside, but all were reluctant to do so. When Iku insisted, one student explained, “without rules, I don’t know how we are supposed to ‘play’.” His words came as a shock to Iku: It never occurred to him that for this generation, whose definition of ‘play’ is dominated by game consoles, the real world lacks ‘rules’ for them to play with others. As soon as he had this a-ha moment, Iku decided to spin out of the original team. Together with others the team came up with a pair of sneakers, equipped with motion sensors that go hand-in-hand with smart phones. The device would tracks the location of each player, and the players in the proximity can compete against others over the area they have captured, or based on any other attributes the device could track. The device was simply put, a rule-making device, which enables users to convert real space as scenes from a game. When the prototype was demonstrated in the final presentation, the Studio was filled with excitement. A venture capitalist became interested and offered a support to the team.

How did Iku’s start up go in the end? In fact, the team decided not to pursue. The team even declined the offer from the venture capitalist. As the entrepreneurship became reality, they seem to have been struck by the amount of commitment the project requires, and most of all, seemed to struggle to fuse an intrinsic motivation to start business.

So what was different between Hiro and Yoshi, who successfully started their businesses, and Iku, who did not? All three cases had very strong and attractive ideas, but what ultimately separated the two was the act of rewriting the problem: although both Hiro and Yoshi visited others and were inspired through observations and interviews, in the end, the solution was not only for them, but also, for we, including his own peers: Hiro’s idea enabled him to interact more with his children; Yoshi’s idea was for his colleagues, where everyday communication was often neglected. Meanwhile, Iku did not change who the target users would be, from the people he was inspired. He did not, unlike two others, did not reflect on himself to see, if the idea would have addressed any of his concerns or problems in his life. In other words, he could not develop a sense of co-ownership.

DISCUSSION: ACQUIRING SENSE OF CO-OWNERSHIP THROUGH ETHNOGRAPHY

Many challenge and most fail…becoming an entrepreneur is hard. This is particularly the case for so-called ‘innovation-driven entrepreneurship’ (Aulet, 2013), as entrepreneurs not only need to create products to appeal the market, but create the market itself. Considering what takes place in most people’s lives today, not many would score as low as entrepreneurship rate. Entrepreneurs need a reason why s/he would take such risks, and should have an intrinsic motivation, or to be more precise, ‘a mission.’ And as we saw from these three cases, a mission is often generated through the process of research and its reflection creating a ‘shared space’ between oneself and the potential customers. In this sense, to-be-entrepreneurs need research not only as a way to understand the customers, but as a process of dynamic interaction with customers in order to co-create the ‘shared space’ as an innovation opportunity.

This resembles to the past discussions what roles that ethnographers can take. Ethnography is powerful to unleash us ethnographers to become “agents of change.” We are often privileged as we are intrinsically in the frontline of corporate, social and academic practices. Brun-Cottan described us as “ontological choreographer” since “we owe the adequacy as well as accuracy of those representations to those we study, to those to whom we report findings, to those who hire us, to those with whom we work (designers, engineers, marketers, sales representatives, and so on), and to those who will be the consumers of ‘our work’ itself (our colleagues, our discipline)” (Brun-Cottan, 2010). We literally are in the center of problem sphere where multiple knowledges and multiplicities of meaning are elaborated. Therefore we can ride out the role being humble trustees of informants; we need not stick to “as if” we were they, but rather encourage us to own them.

As Depaula et al. argued we are no longer mere researchers, but are invited to contribute as product developers, business strategists, dealmakers, and corporate narrators (Depaula et al., 2009). For this transformation, we should utilize our knowledge, experiences, skills, our unique perspective to endow us an edge – creating interesting possibilities to stay relevant. Authors of this paper also discussed what roles we can take the social activist and interventionist stance (Ichikawa et al., 2013): Under the imperative circumstances of transforming the tsunami devastated area in the northern Japan, we spontaneously undertook a role to articulate an array of resources such as community leaders, high school students, professionals in broad areas, NGOs, and philanthropy organizations, from their knowledge, skills, passions, network, materials, to funds in order to create a force to move forward.

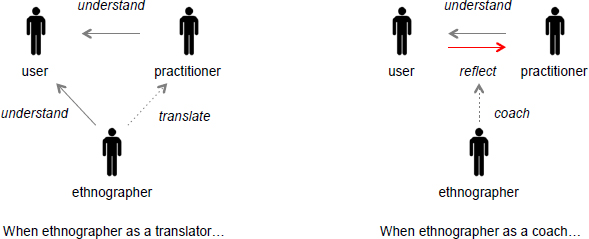

How might we help to-be-entrepreneurs to tap the power of ethnography? How might we help them to go beyond gaining “favorable insights” and to build sense of “co-ownership” through research? One idea we suggest is to detach ethnography from ethnographer, in particular, by ethnographer shifting his/her role from a translator to a coach. Figure 2 shows how this idea works. When ethnographer is a translator, s/he understands users through research, and translates their needs, desires and aspirations for practitioner such as developers or entrepreneurs. These practitioners would then utilize the outcomes of the research but having ethnographers as mediators, it leaves distances between the user and the practitioner, which makes them difficult to gain a sense of co-ownership. Meanwhile, what if ethnographer is a coach? Instead of passing on the messages from the users, the coaching brings practitioners to the frontline of research and through that, helps practitioners to extract, or to reflect their motivations and concerns, which overlap with the users. In other words, coaching by the ethnographers is the key for practitioners to co-own users’ concerns and problems.

Figure 2. Comparison of the roles ethnographer to take: As a “translator” and a “coach.”

Being a good coach in this particular situation has not been well speculated, but anecdote that Hiro left in his experiences in Innovation Studio provides us an inspiration: When Hiro was asked what has been most helpful about Innovation Studio, he instantly told us that “Oka was always there for me.” Oka is one of the directors and, with his open-minded and casual personality, he is very accessible for participants of ISF both in physically and in mentally. This took us as a surprise as the program provides various supports, including methods, knowledge, cases, advice, and networks to help ideas come true. Despite of all these being offered, one of the most successful graduates of the program appreciates Oka’s presence, his generosity offering time to hear participants stories and try to understand what they wanted. Ethnographers may perhaps be equipped with a rich set of skills, experiences, knowledge, and unique perspectives, in the end we should be aware that we are perhaps valued for being there. This notion suggests that we are being on the new stage – legitimate facilitator of entrepreneurship.

REFERENCES

Aulet, William

2013 Disciplined Entrepreneurship: 24 Steps to a Successful Startup. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Brun-Cottan, Francoise

2010 The anthropologist as ontological choreographer. In Ethnography and the Corporate Encounter. Melissa Cefkin, ed. Pp. 158-181. New York: Berghahn Books.

Depaula, Rogerio, Suzanne L. Thomas, and Xueming Lang

2009 Taking the Driver’s Seat: Sustaining Critical Enquiry While Becoming a Legitimate Corporate Decision-Maker. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2009: 2-16.

Ichikawa, Fumiko, Hiroshi Tamura, and Yoko Akama

2013 What Research Transforms: Ethnography by High-School Students Catalyzing Transformation of a Post Tsunami Community. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2013: 252-265.

Kolko, Jon

2014 Well Designed: How to Use Empathy to Create Products People Love. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Patnaik, Dev and Peter Mortensen

2009 Wired to Care: How Companies Prosper When They Create Widespread Empathy. Upper Saddle River, NJ: FT Press.

Rogers, Carl R.,

2012 Client-centered therapy. In American Handbook of Psychiatry (Vol.3). Silvano Arieti, ed. Pp. 183-200. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Uchida, Yuki, Fumiko Ichikawa, and Hiroshi Tamura

2014 Powers of Ten: Acquiring Sense of Ownership in Grow. Participatory Design Conference Proceedings (2) 2014: 119-122.