Case Study—This case explores a research and consulting engagement whose goal was to build an investment case for a new type of 21st century gym for the spirit, mind, and body. The client, a group of well-funded U.S. entrepreneurs, wanted to design and launch a venture that would be positioned to serve the emerging spiritual needs of the proximal future (2-15 years). While the founders were themselves involved in meditation, belief-dependent realism, and a loose collection of westernized oriental and mystic practices and beliefs, they had not yet defined the venture’s specific offering. They suspected that (a) the dominant sociocultural climate of rationalism (e.g. rationalized life choices/paths derived from rationalized worldviews, disengaged relationship with the body and emotion, cynically-motivated wealth creation, etc.) and the lack of embodied and experience-based decision-making and living practices were at the core of a generalized social malaise, and that (b) decoding it and designing a venture to target it, if done right, had the potential to catalyze a movement that could be both highly socially beneficial and lucrative. The case describes the journey to design a research methodology to validate, qualify, and expand their theory, study spirituality in U.S. culture, map the relation of spiritual needs to salient psychosocial problems, create a predictive theory about the future evolution of human spiritual and personal transformation needs, and design a business venture that would serve those needs, be broadly appealing to the U.S. public, and become a profitable company. The end product is multiple things at once: a service, a set of beliefs and practices, a philosophy, an intelligible, intelligent, and attractive system, a community, and a business, and the difficulty designing it and studying a topic as blurry, diffuse, and totalizing as spirituality and how it engenders individuals’ relationship to reality and collective culture presents a particularly interesting opportunity to discuss how a hybrid research methodology of socio-historical research, ethnographic fieldwork, and semiotic analysis provides the correct focus with which to study and theorize around such a slippery subject.

INTRODUCTION

Our consultancy was approached by a group of well-funded entrepreneurs who wanted to design a business venture that would revolutionize the U.S. personal transformation industry by introducing spirituality to the mainstream and “pave the way to create heaven on earth.” They were part of the loosely knit conscious culture movement, and they wanted to create an entirely new type of gym for the spirit, mind, and body which would become the 21st century equivalent of the 20th century’s gym for physical fitness. They thought that just as shaping the body had served as one of the core aesthetic, commercial, and quasi-religious activities of the 20th century, the next large-scale wave had the potential to be just as significant, with great power to fuel both social transformation and the personal transformation industry. Despite being among some of the most accomplished U.S. entrepreneurs, however, the complex nature of designing for such a drastic cultural discontinuity presented a significant challenge they needed help navigating.

The clients were all coaches or followers of a wide variety of personal transformation techniques and spiritual/conscious culture beliefs and practices, from meditation and visualization to motivational speaking and emotional and entrepreneurial coaching. Having embarked on a years-long joint spiritual journey themselves, they were convinced that the power of the loose set of beliefs and practices they called “conscious” could transform individuals for the better, and they suspected that secular Americans were about to become open and ready for their widespread introduction. The consultancy’s tasks were to assess whether this was indeed true, to help them turn their philosophy into a consumable experience, and to design its delivery as a desirable and profitable service business. More specifically, the consultancy was asked to design a research methodology to evaluate U.S. culture’s readiness for a new personal transformation philosophy-based service that would be based on spiritual conscious culture. The results of the research would then serve as the basis for translating the founders’ spiritual philosophies, skills, and practices into a coherent, desirable, and competitive service business.

During the introductory meeting, the clients presented the consultancy with their philosophies and with the wide set of beliefs and practices they held to cultivate the more conscious way of living that they wished for everyone. They believed that the greatest source of individual and societal ills experienced today, from stress and corruption to disease and emotional pain, had its origin in the psycho-social realm, and specifically, in the way that we construct reality. Instead of incorporating the knowledge that emotions provide us about all levels of reality (emotional, professional, spiritual), they saw mainstream western culture as having fallen victim to a reductive and materialist rationalism that was causing people to lead lives that they did not want to lead. Having lost touch with the spirit and the body, with its senses and its emotions, and with the knowledge they give them about themselves had led westerners to accept a material lifestyle-based culture built from the outside in, fueled by fear of missing out, and predicating happiness on the desires of others. In other words, they thought that just like decades ago the lack of knowledge and focus on physical fitness had caused a rise in society-wide physical health problems, a culturally dominant unconscious way of living today was the underlying cause beneath our political, mental, physical, and spiritual malaises.

The solution to this, they claimed, was a cultural change of attitude to accept belief-dependent realism – the belief that if we change what we believe is real and possible, reality itself can expand and morph into a better version of itself. This was an explicit acknowledgement of the anthropological tenet that reality is culturally constructed. Taking it as a basis, they proposed that teaching a set of beliefs and bodily techniques that could help people embody the tenet would make them aware of their relationship to reality and turn them into agents of mass cultural change. Mystical and emotional sensitivity techniques would be crucial to help people find their purpose and give them the personal development skills to actualize it. They drew from the ideas of Abram Maslow, a behavioral psychologist who proposed an innate human hierarchy of needs that culminate in the need for self-actualization, and David Hawkins, an author who charted a path for spiritual awakening based on expanded awareness of consciousness and emotion, to argue for focusing the new service on self-actualization and the cultivation of consciousness. But while this was an exciting philosophical discussion, it was difficult for them to concretely articulate what exactly conscious spirituality was, how self-actualization could be sold and be delivered, or what was the precise philosophy that would be transmitted.

Following this, when asked how they planned to turn the philosophy into a practical business, the founders presented a list of ideas for the business’s offering which included everything from ecstatic dance parties to yoga and meditation lessons, a conscious culture members’ community center, a virtual reality game app, spiritual and personal development classes, and personal coaching. The business model too was far from clear; ideas included a pay-based mobile app, a membership-based community center, pay-per-attendance-based classes, and a recruitment-based multi-level marketing scheme to sell products and generate income for members.

It quickly became clear that the founders had difficulties imagining how their spiritual philosophy would be made into a tangible service and were unable to distill what their concrete philosophy was. They could feel it. It had changed their lives, awakening them to a higher level of consciousness, but they had difficulty describing it as an outward-facing value proposition. The anthropologists leading the consulting engagement understood that the reason for this was probably the mystical nature of their spiritual transformation. What they were hearing were people already on the other side of a mystical transformation, which by its very nature is a phenomenon one must taste in order to understand. This, of course, did not discount the possibility of decoding it and packaging it into a consumable experience, but before delving into the research to gauge readiness for this type of transformative spirituality in the U.S., it would be necessary for the consultancy’s anthropologists to understand what exactly conscious spiritual transformation means and how it is lived. Having suspected this would be the case, the founders had selected an unorthodox business consultancy – one with the research tools and acumen necessary to craft a sharp focus into both the founders’ spirituality and the world’s spiritual needs. They needed researchers who could gain an intimate understanding of the founders’ embodied spirituality to then go back to the world, see if and how U.S. culture would be ready for it, and design a venture and a compelling investment case based on data.

To the consultants leading the project, it was clear that ethnography would play the major role; it would allow them to both distill the founders’ unarticulated mystical philosophy and explore the spiritual needs of U.S. secular people, most of whom did not identify as spiritual or recognize the presence or existence of spiritual needs. But they would also need other cultural research tools to help them gauge and interpret the U.S. market’s readiness for a new kind of spirituality service and to design, size and justify the investment in launching one.

DESIGNING THE RESEARCH

After the initial meeting, the consultants retreated to their office to map and break down the complex challenge facing them and to develop a project plan and a research methodology to tackle it. Interestingly, they had not been presented with a discrete business or interaction problem (declining sales, behavioral or interaction design, etc.); instead, they had to build a foundational understanding of spirituality – the loose, diffuse, and heterogeneous set of secular and non-secular beliefs and practices that mediate our relationship to reality – and use it to design a new personal transformation service meant to exist within an entirely new paradigm and to become the 21st century equivalent of the 20th century’s gym and church. In concrete terms, the engagement’s goal was to build an investment case for a new type of 21st century gym for the spirit, mind, and body that would be positioned to serve the emerging spiritual needs of the proximal future. A still unclear mystical spiritual philosophy and set of personal transformation beliefs and practices had to be articulated and packaged into a consumable philosophy that would be desirable and would meet the emerging spiritual needs of U.S. mainstream culture, including those of people who did not yet identify as spiritual.

They began by noting that the highly ambitious end product would need to be multiple things at once: a philosophical point of view on the nature of reality, an intelligible and intelligent system of beliefs and practices that users would adopt, a community, and a service business. In order to simplify it, they reduced it to a simple three-pronged structure: First, they would have to craft a philosophical view of the world based on belief-dependent realism which would have to resonate with contemporary U.S. culture; second, they would have to turn that philosophical view of the world into consumable experiences which would deliver it in an effective and appealing manner; and third, they would have to organize the delivery of the consumable experiences as a profitable business.

The three together would form a value proposition consisting of an engaging philosophical point of view on contemporary life. And it would not necessarily have to take the form of an explicitly spiritual endeavor, for although it would be the underlying philosophical narrative delivering the value by helping people make sense of the world and their lives in a new way, like most major fitness and lifestyle movements (e.g. yoga, Crossfit), that narrative could be translated into a value proposition that would be acted out and consumed in the form of products and services.

Since this was still dangerously abstract, the consultants then broke down the challenge into four manageable pieces: 1) understand and articulate the mystical spirituality of the founders and its underlying cultural values, (2) identify the key unmet spiritual needs in both spiritual and secular mainstream U.S. culture, (3) build a predictive theory about the future trajectory of spiritual and personal transformation needs, and (4) design a desirable, competitive, and profitable business venture based on the founders’ philosophy to serve those needs. For each of them, they chose an evidence-based research methodology as follows:

- 1) Understand and articulate the mystical spirituality of the founders and its cultural value.

Aim: Grasp the founders’ philosophy rationally and experientially to determine its potential and find a way to articulate it and make it intelligible for an audience that has not yet experienced and adopted it.

Methodology: Ethnographic immersion into the founders’ lives and their spiritual personal transformation community to build an understanding of their mystical spiritual philosophy from an internal vantage point. Ethnography would attempt to let the consultant-anthropologists move into and out of the founders’ mystical experience of reality so they could (a) learn its value to help the founders articulate it with the right language for the world, and (b) know what to look for in mainstream culture to gauge its readiness for spirituality. - 2) Identify the key unmet spiritual needs in both the spiritual and secular U.S. population.

Aim: Having understood the nature and value of the founders’ mystical experience, to gauge mainstream U.S. mainstream culture’s readiness for it.

Methodology: Ethnographic immersion into secular and representative Americans to understand their articulated and unarticulated spiritual and personal transformation needs and the driving forces behind them. Also, to map the language with which the spiritual philosophy and its value could be articulated to be intelligible, relevant, and desirable for the mainstream. - 3) Build a predictive theory about the future trajectory of spiritual and personal transformation needs.

Aim: To project forward the driving forces behind the spiritual needs of Americans and validate the founders’ hypothesis that mainstream U.S. culture would soon be ready for widespread acceptance of spirituality.

Methodology: Carry out a broad socio-historical analysis of the spiritual and personal transformation practice and belief systems of the 20th century to identify the driving forces behind them (economic/material, social/cultural, and/or spiritual/psychological). Then, combine those findings with those from the ethnographic research to see if and how the founders’ spiritual transformation philosophy could be valuable and desirable. - 4) Design a desirable, competitive, and profitable business venture based on the founders’ philosophy to serve spiritual and personal transformation needs.

Aim: To package the founders’ philosophy into a tangible offering that would be both valuable and desirable for mainstream U.S. culture and a profitable and scalable business venture, to competitively position the venture in the personal transformation space, and to build an investment case to raise the capital needed to launch the venture.

Methodology: Semiotic analysis of the current and potential competitors in the US personal transformation and spirituality space to determine the venture’s ideal positioning, strategic design of the venture’s offering and business model informed by the analysis of the previous three research phases, and quantitative market sizing and financial projections to justify the capital investment.

After presenting the hybrid research methodology to the clients along with an eight-week plan to tackle it, the consultants turned to the question of how to use ethnography to establish a vantage point into the embodied experience of conscious spirituality.

PHASE 1: ETHNOGRAPHY OF MYSTICAL CONSCIOUS SPIRITUALITY

The aim of this phase was to use ethnography to gain access to the founders’ mystical spirituality, understand its value from within, and distill it into an intelligible philosophy for an audience that had not yet gone through it. Ethnography would let the two anthropologists leading the project immerse themselves into the founders’ world to experience their philosophy from within; only then would they be able to do what the founders could not – distill the mystical experience into a tangible and intelligible philosophy – after exiting back into their original reality. In anthropological terms, they would learn the founders’ emic perspective (the view from within the founders’ spirituality) and use it to develop an etic perspective (the view from the observer’s perspective) that would appeal to potential consumers, both spiritual and non-spiritual.

Before developing research questions and informant recruitment criteria, it was necessary to create a theoretical framework to define spirituality and to provide the consultants with concepts and language to study it. Spirituality, unlike the more traditional consumer cultural phenomena they were used to studying, was not just a phenomenon itself, but also a mode through which the phenomena of reality in general could be experienced and interpreted; in other words, a constitutive component of experience itself. To think about that mode, the consultants turned to the work of sociologist Emile Durkheim who presents religion as both rooted in social convention and as a lens nested between a person and their reality truly endowed with the capacity to reshape their experience of reality:

A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden – beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them.

(Thomson 1982, 129, excerpt from The Elementary Forms of Religious Experience)The general conclusion…is that religion is something eminently social. Religious representations are collective representations which express collective realities; the rites are a manner of acting which take rise in the midst of assembled groups and which are destined to excite, maintain, or recreate certain mental states in these groups.

(Thomson 1982, 125, excerpt from The Elementary Forms of Religious Experience)This system of conceptions is not purely imaginary and hallucinatory, for the moral forces that these things awaken in us are quite real – as real as the ideas that words recall to us after they have served to form the ideas.

(Bellah 1973, 160, excerpt from The Dualism of Human Nature and its Social Conditions)

Thinking about spirituality similarly to religion as a collectively informed way to conceive of the real that is derived from the sacred was a useful way to destabilize the rationalistic and objective conception of reality held by the consultants and secular mainstream Americans. Reality, seen through this lens, was not singular and objective but rather malleable and dependent upon the specific system of conceptions of the spiritual community. It also opened the door for the ethnographic immersion to provide the key pieces needed to distill the system of conceptions: the sacred and forbidden things that were set apart, the beliefs and practices that relate to them, and the rites and manners of acting. Interestingly, Durkheim had also identified the chasm that existed between those within a religion and those seeking to explain it, accurately foreshadowing the founders’ inability to articulate the philosophy behind their spirituality themselves:

That which science refuses to grant to religion is not its right to exist, but its right to dogmatize upon the nature of things and the special competence which it claims for itself for knowing man and the world. As a matter of fact, it does not know itself. It does not even know what it is made of, nor to what need it answers.

(Bellah 1973, 205, excerpt from The Elementary Forms of Religious Life)

The first question, then, was what need was being answered in the founders’ spiritual community through spiritual beliefs and practices. And to answer it, the consultants would use themselves as the instruments, invited by informants into their reality to then return to their own and interpret their journey.

The next step would be to plan the ethnographic fieldwork. The ethnographers decided they would spend time with both the five founders and with other informants who were on similar spiritual and personal transformation paths as the founders but who were not personally connected to them. Eight of these latter informants were selected to participate in in-home ethnographic interviews following a screening process that included a wide range of interpretations of spirituality (e.g. path of transformation, personal growth, self-actualization, mindfulness, consciousness) and that fulfilled gender and life stage quotas. During the ethnography, the researchers would have to learn each informant’s language to probe deeply into his or her belief system and way of constructing reality. To serve as a guide, they developed the five research themes and built a comprehensive set of research questions and an interview and activity guide for each. The themes and their key research questions are summarized here:

- Daily life and personal history – Who are they and where are they now in their lives? What is meaningful about life? What gives them hope and is sacred and forbidden to them? What are their core beliefs and practices?

- Ideal self and obstacles to it – What would make life more meaningful? Who would they like to be? What would their ideal community be like? What major obstacles, articulated and unarticulated, must they overcome? What is their relationship with time? With death?

- Worldview and available offerings – What is their outlook on the world and where does it come from? What is their role in the world? What is an ideal world? What beliefs, practices, communities, and services do they see as helping move the world towards the ideal? How do they see and experience existing spiritual and/or personal transformation offerings?

- Moments and places of transformation and community – What have been their key moments, groups, and phases of growth and transformation or connection with others, themselves, and reality? Why were they transformative? How are transformative moments constituted and what is the role of other people? What practices are woven into daily life intended to help them transform and grow and why and how are they believed to work?

- Reflections on technology (technology broadly interpreted as any external tool, physical or immaterial, that could augment their ability to reach their potential as humans) – What kinds of technologies bring meaning to life and remove obstacles to a better life? How are spiritual and personal transformation offerings, communities, and services perceived?

The intimate and profound nature of a person’s spirituality, worldview, and relationship with time, death, and other research questions meant that the ethnographic interview would only be successful with a very high degree of intimacy. Direct questions could not be asked; rather, a nuanced conversation, which would involve the ethnographer volunteering much of his own life, would be needed to build intimacy and guide the conversation. Before going to the field, the consultants created an interview guide with a flow of questions designed to gradually build intimacy and with the semantic flexibility to accommodate the diversity of informants’ experiences. More than anything else, however, success would depend on the degree to which the ethnographer could establish a deep and meaningful conversation – a joint journey led by the informant into a new place – as opposed to an exchange of information; only then would the ethnographer be able to be pulled into the informant’s relationship to reality and be able to see the lens through which they experienced reality. What followed was a fascinating ethnographic immersion into a diverse set of 13 individual realities, all imbued by a strong spirituality.

The consultants traveled to the founders’ city where they carried out five half-day in-home ethnographic interviews with four women and four men participants and where they also immersed themselves in the founders’ lives. The two groups differed in that the founders, as ethnographic subjects, knew the researchers’ intention and were consciously trying to teach and imbue them with their view of the world and of reality. Activities included long and animated group discussions in their office as well as informal gatherings in their homes. On the other hand, the recruited participants knew only that they were part of a research study for a new personal growth and transformation service, and it was up to the ethnographers to frame and lead the exploration of their spirituality and cultural reality. The contrast between the two groups provided a valuable tool which allowed the consultants to identify what those with and without a proselytizing intention had in common, i.e. to distill the essence of conscious spirituality regardless of participants’ intentionality, level of awareness, and relationship to the research. It also let them explore the recruited participants’ unmet needs and how they might be satisfied by the system of beliefs and practices held by the founders.

After an intense week of ethnographic fieldwork, the consultants returned to their office. The intimate ethnographic encounters had elicited strong reactions in them, both of resistance and attraction to the manner in which the informants defined reality. Once home the consultants were able to engage in the process of shifting between their rationalistic view of reality and the newly gained insight into the perspective of the research participants. This reflexive activity allowed them to clearly understand and interpret their cultural worlds. Conversations, field note writing, and pattern recognition sessions led the consultants to an initial list of seven ethnographic findings common to all participants and characteristic of adherents of conscious spirituality:

- Reality was read and experienced more intensely and with a sharper awareness as one progressed through a journey of internal truth that consisted on cultivating self-knowledge from within. Focusing on the body and emotion through both specific techniques and willful consciousness of experiencing life and making decisions from the heart led to a feeling of awakening dormant organs of perception and to a feeling of higher awareness.

- There was an experience of transformation lived and told as a story with a narrative arch that involved the overcoming of obstacles. A process, triggered either willfully by the desire to change or accidentally by an event such as a life trauma, would lead to a moment of awakening. And only after the transformation, by looking back at one’s old self, would one identify the present higher state of consciousness in opposition to one’s past unconsciousness. Often the desire and apparent necessity to make money and pursue material and lifestyle goals would be a core obstacle that had been obscuring the way forward. Losing a job (forced liberation from the engrossment of material pursuit), a near death experience, and the loss of someone close (sudden and intense creation of a relationship with one’s own death) were common liberating triggers.

- The specific beliefs and practices were widely divergent, idiosyncratic, and creative, with participants drawing from friends, YouTube videos, books, and their own experience in their personal quests for deeper meaning and significance. They would all, however, eventually lead to the desire to create or access a community (real or virtual) of other seekers, and they all devoted discrete time and rituals for the advancement of the growth/awakening/development process. In many cases, the community would include the belief in a social movement of greater consciousness.

- A new interpretation of time and work would emerge, with greater importance given to both. The value of the present would both become an explicit priority and a felt reality.

- There would emerge, spontaneously or through a practice, a time and ritual of consciously taking stock of oneself – of what is important, what is one’s essence, and what to shed –, which would create a deeper and more direct felt experience of oneself. Out of this would emerge the sense that one could choose one’s path forward, the people around one, and what to do with one’s time with greater agency and more deliberate intentionality.

- The mainstream rationalistic and cynical interpretation of reality as solely external and objective became suspect or was rejected as the realization that one had control over reality by changing one’s beliefs grew. Believing that one’s beliefs had the power to change reality (and that there was no fundamental difference between reality and how it was felt/experienced) would trigger a virtuous cycle that would strengthen the belief and lead to its experiential confirmation. Reality went from being something external that was given and over which one had little control to something woven into one’s internal state, over which one could have power.

- A deliberately positive attitude and general sense of love and potential towards life.

Upon further analysis, the consultants identified that before becoming seekers or realizing they were on a spiritual or transformational path, the participants had not been able to articulate the fact that they had an unmet need or desire for spirituality, transformation, or greater self-awareness. This initial lack of a felt need or desire was an important obstacle that would have to be overcome to make the service relevant to non-seekers. They had also found that the central unmet need of those already on the spiritual path was either a lack of time to devote to the path of growth or transformation (usually because of the need to work) or a lack of money (usually because of their strong time commitment to pursuing spiritual growth). The ultimate promise and value, however, went beyond personal transformation; it was social and external to themselves, predicated on the condition that if we all change and embark upon a path of greater consciousness, an entirely new culture and society could emerge:

When I was 17 I already knew who I was and what I had to do. The world, the matrix, call it what you want, is still there and we must live in it, but not by it… If we all change from within then a whole new world becomes possible, right here, right now.

–D (25)

In addition, despite the wide diversity of individual beliefs, practices, and language the informants had used to talk about their spiritual or personal transformation experiences, the consultants were still able to distill their common experience of conscious spirituality into four core elements:

- Introspection: Accessing their own deep thoughts and feelings, accessing the body, and searching for knowledge and wisdom within themselves.

- Kindness: Sharing their time, resources, and internal states with others without any purpose other than connecting

- Exploration: Putting themselves in new situations and with new people with the hope of having enriching and revealing experiences, with a special willingness to explore the nature of reality itself.

- Openness: Making a conscious attempt at dropping pre-conceptions, being open to the mystery of life, and being kind and generous towards themselves and others.

The ethnographic immersion, then, had successfully helped the consultants understand the founders’ spirituality and personal transformation from within. By meeting with both the founders and others on a similar path, they became able to articulate the key components of this loose set of beliefs and practices and build a foundational understanding of the value and meaning of what the founders had been referring to as consciousness, presence, awakening, and belief-dependent realism. They now also understood how this movement was being fueled by the quest for internal knowledge and the belief that reality and one’s relationship to it were malleable and able to be cultivated.

It was unexpected how while on one hand the experiences, techniques, and beliefs of individual informants were diverse, idiosyncratic, and disconnected, on the other hand their modes of relating to reality were remarkably similar (and similarly different from the dominant mainstream rationalistic mode of which the consultants were originally themselves a part). This suggested that perhaps there was indeed a deep common need, true across ages and geographies, which could be awakened. The founders’ hypothesis that mainstream culture’s cynical rationalism was beginning to run out of steam was gaining credence. The next step would be to investigate that in phase two.

PHASE 2: ETHNOGRAPHY OF NON-SPIRITUAL AMERICANS

Having built a foundational understanding of the nature and value of the founders’ mystical experience, it was now time to gauge the non-spiritual U.S. population’s readiness for it. The research, then, would have to determine if the need for the value that mystical spirituality provided was also there for non-seeking secular Americans, and if so, how they felt, filled, and articulated that need and how they perceived existing offerings.

The consultants decided to design a similar ethnographic immersion to phase one, but one that would take place far from the place and community where the founders’ spiritual culture was present. They chose New York City as the perfect litmus test: if a need and openness for the need and value that mystical spirituality could provide be found among secular and successful New Yorkers (those likely to be engrossed in mundane and material affairs), it would be likely that the need was widespread. It would also let the consultants discover how that need was being experienced in a culture that did not have a community or a language structured around it. The recruitment would follow the same gender and life stage quotas as phase one and would target informants who were not involved in any kind of mystical, spiritual, or personal transformation path, but who were self-aware, articulate about their own lives, and open to speaking profoundly about them.

The research themes would remain the same; only the mode of questioning would be different. The ethnographers would have to devote more time at the beginning of the sessions to discover the proper language and life context to speak about informants’ needs for personal transformation and explore the things that were sacred to them. Special attention would also be paid to their perceptions of existing mystical spirituality beliefs and communities and personal transformation services.

After recruiting five participants for half-day in-home ethnographic interviews, the consultants conducted the interviews. There were two men and three women participants, and they included a restaurateur, a finance professional, an education consultant, an architect, and a real estate agent, all in their 20’s and 30’s. They encountered the following findings:

- Despite not devoting any time to spirituality or personal transformation nor desiring to do so, informants readily acknowledged a strong tension between internal truth and external demands, which they experienced as being out of harmony. Some participants reported feeling frustrated that they had to sacrifice their desire to fulfill their full potential in order to succeed socially and financially. Others had experienced a mental health breakdown after discovering that they were living a life out of sync with their internal self. The need to perform to fulfill the demands placed upon them by an external system emerged as a common thread among them. In most cases, they were aware of the tension and had undergone especially tense or traumatic moments that had served to bring the external-internal tension to the surface, after which they had decided they should re-evaluate their priorities and live more in the present. However, most had not been able to do so yet and were having trouble negotiating with themselves and achieving harmony. They tended to use the language of therapy and identity – being, discovering, healing, and working on oneself – to describe the experience. Unlike the first group of participants, they did not attribute the tension to contemporary rationalistic culture and the manner in which it structures our relationship with reality. Participants felt the tension as an individual psychological problem related to identity and authenticity that was meant to be solved either alone or with the help of a therapist.

I cannot live the life I want now because in the system there are conflicting interests. When I leave home I need to turn on and perform so that I can build my business and make enough money to have the freedom and the life I want in the future… I crave those times when I’m myself, pursuing pleasure and not feeling guilty about it, like when I’m with my close friends or play music.

– G (28)After I graduated from college I went back home and went through a very difficult time trying to figure out exactly who I was and what I wanted to do. It was confusing, frustrating… It’s better now that I’m more confident about being an architect, but now it’s all about what kind of architect. It’s most important to do something I believe in, so I’m building my architecture practice. But after a close friend passed away recently I was shaken and felt that I have to find a way to live in the present; how do I do that and still get my career off the ground though?

– M (30)Total panic. At some point I broke down at work and couldn’t go back to the office. I had lost myself. I don’t think I ever really had myself. I was just going through the motions and living for the desires of others, and when I realized it I froze and had to re-examine and rebuild my whole life.

– L (36) - Despite working in highly diverse professional fields, participants coincided in their desire to work towards accumulating the conditions required to be able to choose their own work and own their own time. While entrepreneurship was the language most of them used to express this, it was the perceived benefit of becoming a successful entrepreneur that were motivating their desire: liberation from the desires of others and gaining the ability to own one’s own time and to decide what to do with it. Only then, they said, would they be able to truly do what they felt they were in the world to do.

- All of them expressed the desire to lead more authentic lives and be more authentic themselves. They spoke of authenticity as the mode of being that results from one’s genuine and internal essence, personality, and desire rather than from the felt need to be accepted or rewarded by others or what they referred to as “society”. Having a personal style, living in the moment, and resisting the social pressure they felt was being exercised on them to behave a certain way were examples of how they expressed authenticity. Authenticity’s value and emphasis was especially interesting because it was predicated on the possibility of inauthenticity – shaping oneself in agreement with the demands of others rather than your own. The journey towards creating authentic selves was central and often portrayed as deeply challenging. Moreover, professional and material life emerged as a particularly salient obstacle, for life still took place within institutions that demanded a type of performance that did not allow them to be fully who they felt they really were internally, demanding that they act a certain way. The word “performance” took on a special importance, for it appropriately encompassed both the need to compete and achieve status at work and the requisite that one perform or act a role that was given to them in order to succeed at doing so.

- Two general coping strategies emerged to help deal with the sense that internal search for meaning, identity, and purpose was in conflict with the external need to perform. The first was a decision to postpone life by sacrificing the present to be able to live a full life in the future, for example, by choosing to accumulate material wealth for the future. The second was to accept the tension and to try to enjoy the journey by consuming experiences that provide the feeling of depth and authenticity. None of them, however, were truly solving the problem. Even if one decided to postpone life, one was still aware that the future was not guaranteed and so still wanted to live fully in the present, and even if one accepted the tension and tried to cope, one was alone and had little time to devote to nurturing the quest for the growth and expression of the internal self.

- Informants created sanctuaries in their lives – times and places in their lives where they could be their full authentic selves and cultivate self knowledge; however, they were limited in time and scope, with an emphasis on the removal of suffering rather than with an objective and willful transformational pursuit. These were sacred spaces for them, offering respite from the need to perform, but as opposed to spiritual seekers’ communities, practices, and rituals, they were cast as places of rest and withdrawal from the demands of “real life” rather than as spaces and times of growth, wonder, and exploration. Examples included hiking in nature, unstructured play, therapy, cooking, escape time with childhood friends, and practicing sports.

- Spiritual movements and communities and personal transformation services and books were off-putting. Their esoteric language, distance from scientific truth, cultish associations, and the possibility of ulterior commercial motives were especially problematic.

As the consultants interpreted the data, they were surprised to find that despite having met radically different people who were not on any kind of mystical spiritual path, they all felt a core tension between discovering and being themselves and being successful in the world. Informants in New York City who were not on a spiritual or personal transformation path were aware of this tension and intending to devote more time and effort to discovering and cultivating themselves from the inside out, but they were unsure of how to do it, lacked discipline, and found the available services and communities devoted to it unappealing. In some of them, the tension had even led to a series of private yet debilitating mental health breakdowns, suggesting that this was not an insignificant unmet need.

Unlike participants in phase one, those in New York City were not consciously trying to cultivate or modify their relationship with reality and were not even open to the possibility of a practice that could make it possible, but they were spending much of their resources attempting to cultivate and modify external reality – their stock of capital and their sanctuary places and activities – so as to help increase the present and expected future harmony with their internal selves.

The ethnographic data suggested that although outwardly successful, well adapted, and happy people were not conceiving of their life quest in explicitly spiritual or personal transformation terms, they were deeply involved in a challenging private struggle to explore and deepen their authentic sense of internal self and reconcile it with the situation, needs, and control over their external reality. Even the desire for material wealth, which they overwhelmingly used as justification for their lifestyles choices and major life decisions, was one which they cast within the logic of this struggle; accumulating enough of it to eventually be able to liberate themselves from the need to work for others was the perceived requisite to achieve a full life, i.e. accumulating enough capital to own their own time and gain the freedom to pursue a self-chosen goal, a desire most commonly expressed as the wish to become an entrepreneur.

It appeared, then, that there might indeed be more room than expected within mainstream U.S. culture for the introduction of a mystical spiritual philosophy in the form of a service business which could target the need for harmonizing and exploring the seemingly turbulent rift between internal and external self. Before thinking about how to design it so as to overcome the cultural resistance to the possibility of a mystical and spiritual epistemology, however, the consultants wanted to validate their ethnographic observations and build a robust evidence-based theory that would explain what was going on and orient project future scenarios.

PHASE 3: SOCIO-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS AND PREDICTIVE MODELING

Could it be that what the ethnography had shown was part of an initial crack in U.S. culture’s positivistic mode of relating to reality, and thus the beginning of a change in culture away from rationalist and towards mystical ways of knowing and being? Was it possible that within U.S. mainstream culture there was a growing need to go beyond the scientific positivism that held that the real could be reduced to the observable and the falsifiable and to accept mystical beliefs and a cultural view of reality as shaped and alterable by belief? Perhaps deep forces made invisible by a self-obscuring system or the slowness and grand scale of changes were at work, a tectonic shift that could become the basis for the investment case the founders needed to build and the explanation for a variety of other observed cultural shifts.

Having used the power of ethnography to zoom deeply into people’s internal and local lives, the consultants began to model a hypothesis of what might be emerging as a social need to reconnect with internal truth and go beyond the material solutions that rationalistic modes of relating to reality offer. In order to complete the picture, they now needed to zoom out both temporally and spatially to place the findings in the context of how and why western culture might be changing. This would let them generalize their findings and build a predictive theory about the future evolution of spiritual and personal transformation needs.

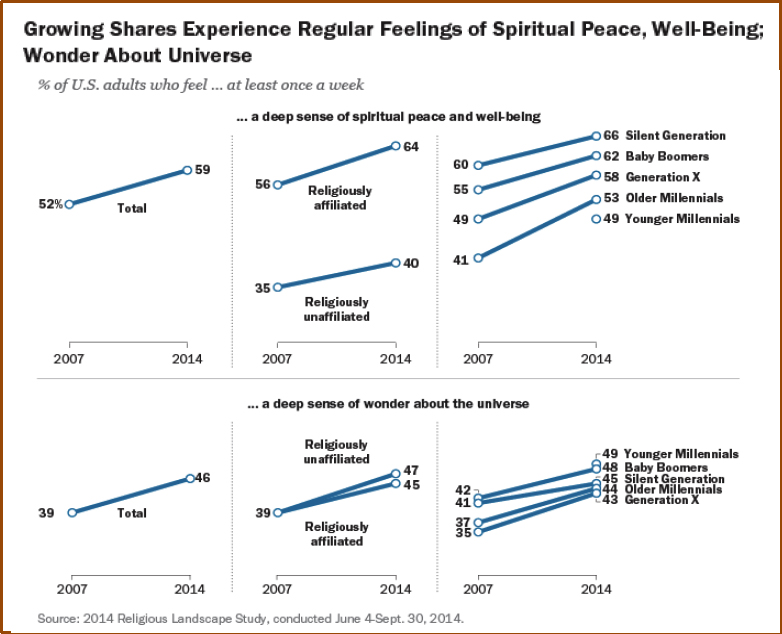

The first step and low-hanging fruit was to look for society-wide statistical evidence of a broad cultural shift. Surprisingly enough, this was not hard to find. Survey data showed that from 2007 to 2014 Americans had simultaneously moved away from organized religion and towards spirituality, having what could be interpreted as increasingly common mystical spiritual experiences – internal feelings of spiritual peace, wellbeing, and wonder about the universe that were not rooted in external or rationalistic observations.

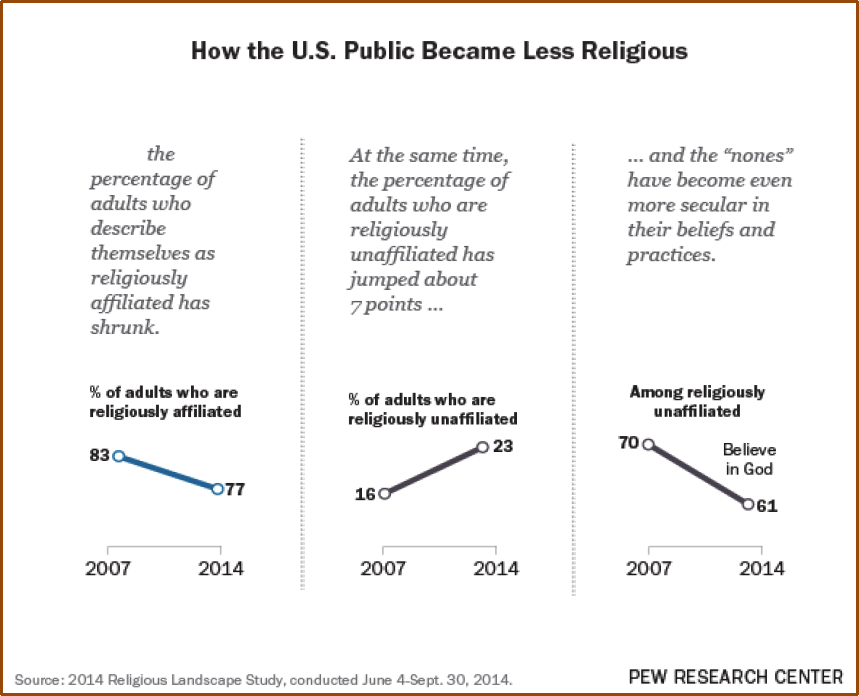

The consultants noted that the simultaneous shifts were of historically unprecedented magnitudes: In only seven years, 6% of U.S. adults had stopped identifying as religiously affiliated, and among the unaffiliated, belief in God had dropped by 9%. At the same time, 7% more U.S. adults reported experiencing regular feelings of spiritual peace, wellbeing, and wonder about the universe, a phenomenon true both among the religiously affiliated and the unaffiliated, and growing faster among younger generations. A tectonic shift did indeed seem to be happening under the surface across U.S. culture. The next question was what was driving it and why.

As a starting point, the consultants chose to carry out a socio-historical analysis to trace the history of personal transformation. Just like ethnography’s power to build insights into cultural realities by rendering the familiar strange and the strange, familiar, history can be used to treat as strange one of today’s largest and most familiar industries and its rationale– the idea of fitness as leisure – to determine whether the forces that led to its emergence were active today. Looking at how and why today’s established personal transformation industries and philosophies such as gyms and fitness emerged in the first place, they thought, could offer clue as to the nature and dynamics of the driving forces behind the need for them.

Physical fitness gyms emerged as a mid-19th century rarified luxury for elites that responded to the rise of white-collar work and sedentary professional lifestyle (Garber 2013). Before that time, economic value was created by work done by muscles. In a world in which only blue-collar work was possible, physical activity and fitness were an economic necessity and the way human worth was conceptualized was intimately connected to the capacity to perform manual work. With the invention and proliferation of the steam engine, however, the means of work of most European and U.S. men, which was also they way they built their identity and how they felt their social value and self worth, came under threat. Even if the muscle power of machines was far from actually endangering the livelihoods of workers, the possibility that it might enter into the collective imaginary triggered an identity crisis that reached deeply into what it meant to be human. If humans conceived of their humanness and self worth as tied to their capacity for manual work and to the product of their labor, the possibility that a machine could supplant both implied a substantial metaphysical threat to what it meant to be human.

It made sense that Romanticism, a cultural current motivated by the desire to elevate what it meant to be human from the material into the transcendental realm, had emerged during this time. It also made sense that those who already did not use their muscles to work, i.e. the European elites and first white collar workers, would pursue “physical activity as something to be engaged in not by economic necessity but by personal choice, [redefining fitness as] a perfectly balanced physique rather than [as] the ability to perform actual physical tasks” (Garber 2013). Physical exercise, then, had become separated from labor precisely at the time that the possibility that men would not be able to keep defining themselves as men by their labor became apparent. As it became obvious that work and value would shift from muscles to minds, cultivating muscles (i.e. physical fitness) went from being within the realm of labor to that of leisure. Having a physically fit body started to become a sign of luxury, for it signified that one did not derive livelihood from the use of muscles. Then, as while collar work became the norm in the US and western European countries throughout the 20th century, physical fitness grew to become one of the world’s largest industries and a cultural obsession. Could it be that we were on the cusp of a similar shift now that the possibility that machines would learn how to think was quickly seeping into the U.S. cultural imaginary? Were we at the beginning of a neo-Romanticism born out of a looming crisis of what it means to be human in the age of artificial intelligence? And what would that imply?

To find out, the consultants tested their hypothesis with a topline semiotic interpretation of contemporary culture. They asked whether they could interpret recent shifts in values and ideals in mainstream U.S. culture as signs that 21st century culture was responding to an unspoken crisis of what it means to be human by attempting to elevate human identity and self worth from its mundane ties to its productive output (predicated on the use of the mind to produce value) and into a more stable transcendental realm. The consultants tested the hypothesis by doing a topline semiotic sweep across contemporary cultural practices and values in the US. The method consisted of applying semiotics, the study of how meaning is formed and deposited in signs, by reading the major shifts in contemporary U.S. culture as signs imbued with meaning. To do so, they first listed the major shifts in cultural values, norms, practices, and consumption preferences from 2006 to 2016, and they then asked whether each one could be interpreted as a sign of a crisis in how people conceive of being human, of a breakdown in associating being human with producing work, or of a new search for meaning and identity outside of the capacity to think and work. Out of dozens of major shifts, they were drawn to the following ones:

- Entrepreneurship had significantly grown as a preeminent social ideal. The 20th century’s idealization of scientists, politicians, and artists had evolved in the 21st century to an overwhelming emphasis on entrepreneurs. The value of becoming an entrepreneur was related to living for oneself and making manifest one’s will in the world, and to attaining freedom from institutions larger than oneself and from having to perform according to their standards. The new U.S. heroes tended to be entrepreneurs (e.g. Elon Musk) – people who created value from their imagination and creativity.

- The recreational use and acceptance of psychedelics as a path towards self-knowledge and self-healing were growing rapidly among the U.S. elite. The rising popularity of ayahuasca, psilocybin, and micro-dosing practices was a good example of the exploration of chemically-induced experiences that explored the possibility that humans could be spiritual creatures that could grow by turning inward and that drugs were not just producers of pleasure but agents of the expansion of consciousness.

- Electronic dance music festivals and transformational festivals, with their collective effervescence (which could qualify as a type of mystical experience) and associated anti-materialist credos, had rapidly gained in popularity. Radical new modes of behavior and social organization were being experimented in Burning Man by a growingly elite and popularized among a mainstream U.S. audience.

- Yoga and meditation, with their promise of delivering internal harmony and a more balanced life, were rapidly becoming one of the fastest growing U.S. industries, with a market value of over $27 billion. And discourse within the world of yoga was not only about the health and performance benefits of the practice, but also increasingly about the intrinsic value of the spiritual growth that could come from yogic practice.

- The value of nature and the desire to spend leisure time in pristine nature were on the rise, analogously to the 19th century’s turn to nature as a pathway to the sublime. Trail running, surfing, cross-country skiing, glamping, and eco-tourism had become the fastest growing recreational activities in both the U.S. and Europe. All are premised on the notion that communing with nature has intrinsic value and the power to transform the individual by putting him in contact with forces larger than him and more elemental than those found in rationality-driven civilization and by giving him the space and inspiration to turn inward.

- A preoccupation with authenticity and with the need to find oneself and one’s purpose as an individual had grown to become a central psychological concern of young Americans. The crafting of identity and identity politics had become a U.S. obsession. And the craft movement in the consumption sphere had raised the profile of authentic brands and products and castigated mass-produced ones. All three could be interpreted as signs that Americans were increasingly thinking of their value as tied to their ethnic and individual identity and to their authenticity in self creation and consumption rather than to the product of their work.

- The new entrepreneurial elite was embracing formerly frowned-upon collective endeavors to experiment with a radical and deliberate reorganization of social norms (e.g. free love). The quest for a techno-utopia coming out of Silicon Valley was drawing close to alternative transformational festivals like Burning Man, pushing formerly fringe collectively experimental ways of being in the world to the center of aspirational culture.

- Statistical and ethnographic findings were showing that Americans of all ages were rapidly and overwhelmingly abandoning tying their identity to their work and affiliation to structures larger than themselves and were instead tying it to narratives of personal growth (Silva 2013).

- Experiences that could transform you (e.g. travel, food, sociality) had risen in value relative to the consumption of physical products, which could be bought with the rewards from work. Creating yourself and chasing experiences that would enrich you were growing in value within the realm of consumption.

An explicit personal search of deeper meaning, a turn inwards and away from the traditional institutions and authorities of knowledge creation, an explorative openness towards transcendental and introspective experiences, a weakening of the connection between work and identity creation, and the embrace and idealization of radical experimentalism and mystical experience seemed to be on the rise. And although not tied together or causally back to the consultants’ hypothesis, the observations did seem to provide strong circumstantial evidence for the theory that U.S. culture is on the cusp of a discontinuity triggered by the threat of AI to how people conceive of what being human, working, and producing value means, a phenomenon similar to the 19th century’s cultural response to a world of blue collar work threatened by the steam engine. In other words, if contemporary Americans were conceiving of themselves and building their identity as humans largely in terms of their capacity to think and perform valuable work, there is evidence to suggest that the conceptual emergence of AI was causing a redefinition of what it means to be human, shifting away from the ability to think and towards an exploration of affective, spiritual, and transcendental anchors. And if such a seismic cultural shift was indeed in motion, it would serve not only to explain and predict broad shifts in consumption preferences, but also as a strong case for investing in the creation of an entirely new service space of spiritual, emotional, and mental fitness as an end in itself.

The theory suggests that founders’ and their community’s mystical spirituality is not an isolated cultural phenomenon, but rather symptomatic of how emerging U.S. culture was reacting to a wide cultural shift driven by deep forces of secularization, identity building, and technological change. The personal struggle to harmonize interior and exterior personal realities observed in the ethnographies of phase two, then, can be interpreted as symptomatic of a growing fissure in rationalistic U.S. culture – the beginning of the need to tie what it means to be human and produce value to something other than the capacity to reason. The theory, though not unequivocal, provided compelling evidence that we were in the midst of a broad and significant discontinuous shift in U.S. culture which could generate a valuable investment opportunity in a personal transformation service that would offer mental and spiritual fitness as a luxury. It was a case for investment in what could be the beginning of an entire industry.

Now that the consultants had an understanding of both the mystical spiritual phenomenon and the forces in U.S. culture driving the demand for it, the project’s remaining challenges were to size the investment opportunity and to strategically design a venture that would deliver the founders’ mystical spirituality in a way that would be appealing to the mainstream, bypass contemporary culture’s ideological resistance, and compete successfully against existing and potentially new contending offerings.

PHASE 4: SEMIOTIC COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS, STRATEGIC VENTURE DESIGN, AND QUANTITATIVE MARKET SIZING

The consultants decided to organize the last phase in two parts. First, they would map all potential competitors and take their existing knowledge from previous phases to design a concept for the venture which would meet the U.S. market’s emerging spiritual needs and successfully compete against existing and potential new market players. Then, they would quantitatively size the market opportunity to justify the investment in the venture.

Sizing a market and mapping competitors’ positionings in it is generally a straightforward process when done within established industries with clear boundaries. It is a task widely performed by strategy and marketing consulting professionals following established business practices. The consultants, however, were faced with an industry that would be large and meaningful but did not yet exist – an entirely new space of spiritual personal transformation which would likely combine services that already existed with new emerging ones to eventually coalesce in the mid-21st century’s equivalent of the 20th century’s physical fitness industry. As a result, they would have to creatively use the ethnographic, socio-historical, and semiotic findings to draw boundaries, making an entirely new industry tangible.

Step one required finding all existing potential competitors across all relevant industries and mapping which culturally resonant narrative each was using to appeal to mainstream culture; in other words, what their positioning in the market was. The consultants did this in two-steps:

- They used the socio-historical analysis to create a criteria for existing industries and services that were already serving the emerging spiritual need identified in phase two as a tension between internal and external reality, but that were not yet grouped together as an industry. The group included everything from EDM music festivals and personal coaching to a variety of sports, spiritual content producers, and lifestyle brands. As opposed to listing entire industries (e.g. physical fitness), only the specific players within each that were identified as addressing the spiritual needs identified in phase two were selected (e.g. Crossfit, EDM music festivals and nature sports yes; basketball and country music fairs no).

- They performed a semiotic pattern recognition analysis on the identified players by grouping them into larger categories of same or similar cultural narratives. In other words, they saw each company as a sign imbued with meaning telling a culturally resonant story about itself (e.g. yoga: creating a harmonious life in a non-harmonious world; Crossfit and coaching: increasing performance to tackle external reality challenges). And they grouped all of them into a handful of semiotically categorized codes.

They found they could group all players into three high level semiotic spaces, and they also found that neither was ideally suited to meet emerging spiritual needs. Each of the three cultural narratives demanded something from its users that was not aligned with the desire for internal-external harmony and transcendental individual self discovery that the ethnographic research had uncovered, so that while these services were meeting Americans’ present personal transformation needs, they were not ideally positioned for the cultural shift to come. There was a fourth space, however, largely unexploited, that could combine the need for deeper and more authentic meaning, the luxury of spiritual and mental fitness for their own sake, and the path towards entrepreneurship in a single resonant cultural narrative. Playing within this space, the consultants concluded, would simultaneously meet existing needs and provide a path through which to deliver the founders’ mystical spiritual philosophy as a service in a way that would differentiate and insulate them against competitors. They built a semiotic definition of this fourth space that described its cultural narrative, target audience, brand anchors, and boundaries within which the new offering would be articulated and positioned – a high level strategic document that the venture’s execution team could follow.

Now that the consultants had created a competitive positioning, it was time to take all the insights they had gathered so far to create a concept and value proposition for the new venture. They triangulated the insights from all phases and developed a high level concept based on the principle that exploring the body, mind, and spirit potential for their own sake among a community of people would become the ultimate luxury in the coming era of thinking machines, and that packaging the founders’ mystical spirituality within the competitive positioning they had crafted would guarantee its mainstream appeal and bypass cultural resistance to current spiritual offerings. The concept’s value proposition was based on providing an intelligible and intelligent system of services built around a membership-based community, with both the services and the community specifically designed to ease the tension between discovering and being yourself and being successful in the world. The concept’s services and community would provide members with the skills and techniques to explore themselves introspectively, intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually, and with the skills and network to pursue opportunities to self-express and embark on entrepreneurial quests. And the founders’ mystical spiritual philosophy would be packaged and delivered through some of these services and as media content. Based on the concept, the consultants worked with the founders to outline the venture’s curriculum offering, business model, membership recruitment criteria, experience design principles, and operations, and to write the externally-facing copy to present to investors.

The final task of the project was to build a quantitative sizing of the investment opportunity for the founders to use as an investment case. The traditional market sizing process used by traditional business consultancies could not be used, however, because what needed to be sized was a market for spiritual transformation that did not yet exist. It was interesting to note that the result of the sizing would be close to a venture capitalist investor’s dream – a highly meaningful new market that will likely emerge but that still does not exist. The problem was that such investors want to see both evidence-based numbers for the size and growth of the opportunity and evidence for the fact that it will emerge. The work of phases two and three provided the latter, but in order to build the former the consultants had to creatively design a way to size the market for personal spiritual transformation that they had theorized would emerge out of an impending seismic cultural shift.

The consultants used the insights from the ethnography of phases one and two to find a set of market segments that could be used as proxies to size the commercial opportunity; in other words, they drew the boundaries around the hypothetically new industry by using the ethnographic insights to find the existing industries that were already targeting what would become spiritual needs. The ethnographic insights provided the set of needs that were spiritual but that were not being articulated as such yet and that were being driven by the cultural shift identified in phase three. These were needs such as crafting an authentic identity, finding harmony between internal emotions and external reality, etc. that non-spiritual (phase two) Americans experienced as personal psychological and lifestyle challenges and that spiritual (phase one) Americans experienced as spiritual challenges.

Once they listed those needs, the consultants identified the existing market categories that were already creating value by serving them. They saw that they fell into four vertical categories: cultivating body, cultivating body-mind, cultivating mind, and cultivating spirit. Each of them contained a number of industries (e.g. wellness spa’s and yoga within cultivating body-mind; organized religion and self-improvement within cultivating spirit). After mapping industries under the four verticals, they split them into two groups: target markets – those that had significant overlap with the venture’s concept in how they would serve the needs (e.g. personal coaching) – and adjacent market segments – those with less of an overlap but which could serve as good proxies to gauge the venture’s long term market potential (e.g. psychotherapy).

Following traditional market sizing methodologies with data gathered from industry reports, the consultants calculated the total market opportunity by adding the size of the target markets in the U.S. and calculated their combined projected market growth rate. They then calculated the combined size and growth of adjacent market segments. Interestingly, they found that while the combined size of adjacent segments was over ten times that of the target markets, the growth of adjacent segments was negative, while that of target markets was positive and over 10%/year. This was a sign that segments that were already positioned closer to the venture’s value proposition were growing, while those farther away from it were shrinking – another piece of evidence in favor of the predictive cultural shift theory of phase three.

Finally, the consultants used data from the industries identified to size the addressable market by calculating the size of the target group and its willingness to pay, and they built a revenue and cost structure, calculated break-even points, and projected different roll-out scenarios with a range of liberal and conservative assumptions. In the end, by triangulating the insights from the ethnographic research with traditional business tools, they were able to deliver a market-sizing model for an industry that is still inchoate but that will become highly meaningful.

As a result of their ability to use the insights derived from ethnographic, semiotic, and socio-historical research and to integrate them into traditional business methodologies of investment casing and market sizing, the consultants had given the founders an evidence-based investment case and a business venture concept that they would go onto bring to reality.

Alejandro Jinich is an applied anthropologist and economist. He develops culture-based predictive models and social theory for the consultancy Gemic in New York where he has studied the phenomenology of consumption, spirituality, finance, nature, and time and has advised executives of Fortune 500 companies across industries. He holds an honors degree from Columbia University.

NOTES

Acknowledgments – The author would like to thank Johannes Suikkanen and everyone at Gemic for their personal and intellectual guidance and inspiration, as well as Maryann McCabe for her insightfulness and flexibility as commenter.

REFERENCES CITED

Bellah, Robert N.

1973 Emile Durkheim: On Morality and Society, Selected Writings. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Garber, Megan.

2013 “Going to the Gym Today?” The Atlantic website, January. Accessed May 3, 2015 http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/01/going-to-the-gym-today-thank-this-19th-century-orthopedist/266768.

Masci, David and Michael Lipka

2016 “Americans May be Getting Less Religious but Feelings of Spirituality are on the Rise.” Pew Research Center website, January 21. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/21/americans-spirituality.

Silva, Jennifer M.

2013 Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in the Age of Uncertainty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, Kenneth.

1982 Emile Durkheim. London: Tavistock Publications.