If you follow news about digital self-tracking, you may have heard about Chris Dancy. He appears regularly in the press and has become widely known as “The Most Connected Man on Earth.” Reporters generally characterize him as the epitome of a digital self-tracking devotee, a veritable cyborg in the flesh who has become all but isometric with his data.

Chris’s collection, in fact, started out analog. Long before he found his way to Fitbit and Twitter scraping software, Chris lovingly assembled life-size scrapbooks filled with paraphernalia from years gone by. These collections often feature centrally in narratives of Chris, but they largely stand as silent backdrop, their clutter a foil for his digitally streamlined life. His digital data are associated with purity and order; his boards represent the mess he has cleared from his life.

This contrasting representation of his digital and analog collections reflects a powerful cultural understanding of digital data as something that can be cleaned and have purifying effects. Although in specialist circles we’re increasingly aware that “raw data is an oxymoron,” much more widespread is the view that data can move progressively from dirty to clean. This view misrepresents the enduring social complexities of data. A chaotic scrapbook – where human choice is evident in the assemblage, objects overlap and compete for space, dust gathers or is carefully wiped in moments of reconnection – may in fact be a more appropriate image for the inherent messiness of digital data sets.

The Narrative Journey from Messy to Clean

Photos of Chris’ analog archive sometimes decorate articles profiling his digital habit. An exposé about Chris published in Mashable includes an image of him seated regally in an ornately carved wooden chair against a backdrop of loose paper, receipts, photographs, and seemingly random artifacts. The article provocatively begins: “The walls around him are a scrapbook of his life, pinned with foreign currency, concert tickets, and pictures of his icons, like Michael Jackson and Andy Warhol.” But abruptly, the author turns to tech, never reflecting on the analog.

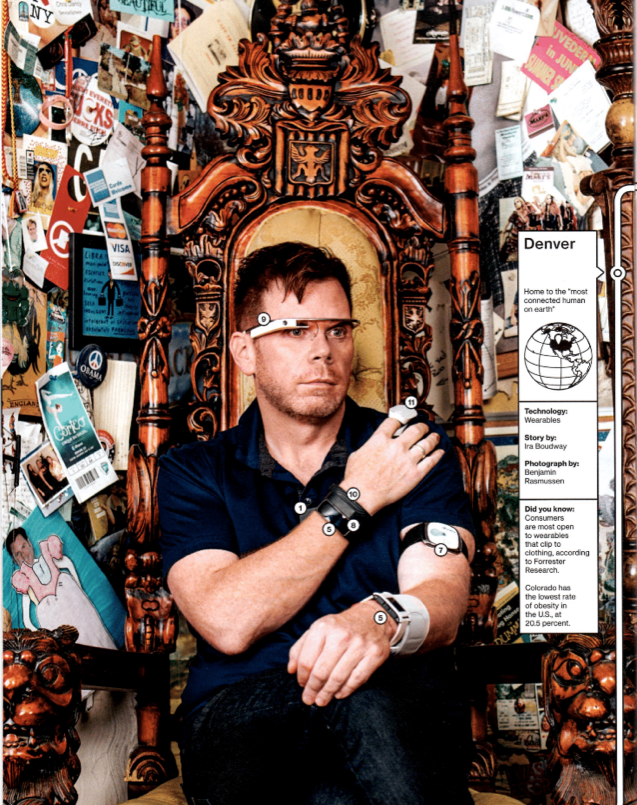

In a photograph taken for Bloomberg, Chris’s boards also adorn the background, but the author and editors have focused our attention on the many gadgets he wears to monitor his life by adding bullet points that prompt readers to click on the tiny red dots peppering his body so they can learn more about the data he collects from each device.

Photograph by Benjamin Rasmussen for Bloomberg Businessweek. Used with permission.

In both accounts, Chris’s boards and the data to be derived from his devices are framed as binary opposites of one another. The boards chiefly impress in their mess. They appear as chaotic shrines to memory and cultivated identity filled with souvenirs from the past, tributes to places he’s been, things he’s seen, experiences he’s lived through, and challenges he’s overcome. But his digital data are associated with purity and order. The boards overflow with tchotchkes – a muddle of kitsch culled from personal memorabilia erupting behind him – the data appear clean, standardized, perusable, streamlined. The boards make an impression on the senses; the data appeal to one’s sense of structure.

Chris’ progression from an analog “collector” to digital “tracker” is central to the narrative because the boards symbolize the clutter he has cleared from his life. Since he took up digital self-tracking he massively reorder his life: he’s lost weight, shed poor habits, ended bad relationships. In older photographs he is often pictured as overweight and unkempt, gazing timidly through oversized glasses, wearing an old and wrinkled T-shirt. These “before” headshots are placed in stark contrast to the sleek, trimmed physique and more finely styled hair in the “after” shots. When associated with the boards, Chris appears a man bogged down by his past; when symbolically aligned with his digital collection, he is styled as a focused man purposefully gliding into the future.

Chris Dancy as featured in Showtime series Dark Net. chrisdancy.com

The narrative juxtaposition of boards to data reflects the dominant view of data as a coherent and logical arrangement of points. It also echoes the popular view that data both require “cleaning” and help to produce “clean” knowledge. This connection between the purity and order secured by data is strengthened by the commonplace association between data and water.

Digital data are often said to “flow” between devices and bodies; gather into seamless “streams,” “pools” and “lakes” until they empty out into immense “oceans” or coalesce into abstract “deluges,” and “floods.” When data are cast as clear and as dynamic as water, they can appear as a fearsome force, as a natural resource, and to slowly accretes in ever more rarefied and momentous ways, creating collections that are all but bordering on the complete. However, these renderings also sanitize the way practitioners, marketers, and reporters talk about data and the lives they trace. Data cleaned as though by water, data seen as clear as drops of water, are often viewed to have vital purifying effects. Data thus often act both as agents and as mechanisms of (personal) clarity.

Cleaning as a Social Process

This narrative sees digital knowledge-making as a process of patient distillation, of methodically getting through the dirt to reveal the thing itself. The fallacy of this linear logic was unpacked half a century ago by anthropologist Mary Douglas in her classic text Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Douglas shows that dirt is the consequence of historical and social agreement about what to count as clean. In other words, dirt is not disorder, but the outcome of a social order. Shoes on the table, she argues, are not dirty in and of themselves—they are just “matter out of place” (50). Popular metaphors of data that source authority from the purifying effects of water today only pull from a historic concoction that has juxtaposed hygiene, water, and power.

In the Lure of the Sea, for instance, Alain Corbin writes about the relationship between water, status, and class that crystallized in Europe during the Enlightenment. Water already symbolized the purity of both the body and the soul in Christian theology. For writers and artists of the Romantic period, the sublime effects of water also became a central theme. In an age of important scientific and technological discoveries, confronting and enduring the awesome power of nature – often epitomized in artwork of the period by a ferocious ocean – became a powerful metaphor for the domination of the human over the natural, the ascendance of culture over nature.

With the discovery of germs by French biologist Luis Pasteur, water took on an even more important social function as the growing role of hygiene created new forms of social order. Even as late as the mid-eighteenth century, Corbin notes, dirt still carried positive associations. However, with the help of public educational campaigns about hygiene, and eventually with the introduction of plumbing in the home, physical cleanliness gradually became entwined with notions of moral chastity and social purity. Mary Douglas stressed, for instance, that because women’s bodies were seen as polluted by fluids they could not contain, they became associated with irrational nature, whereas male bodies symbolized elevated, ordered culture.

The historical and symbolic role of water continues to defend and discipline a dataset against the imagined danger of physical and social contamination and disorder. Figuring data in terms of water suggests that “dirty” data, like murky water, obscures knowledge. However, rather than look to data to move and act like water, we would do well to ask, as Martin F. Manalasan does in a different context, “how can mess be generative and not just a prelude to a makeover?”

Messing Around

Rather than throw the baby out with the proverbial bath water, several theorists have proposed to extend the liquid metaphor to help register data’s inherent messiness and disorder by revealing the continuous friction that paves data’s way.

Dawn Nafus, for instance, has offered to think of digital knowledge-making in terms of “clots” to express the tenuous ways in which data come together. Instead of conceptualizing data as something that accretes in ever more precise and momentous ways, she suggests the terminology of clots to destabilize the idea that there is anything certain or natural in the way data come together. Clots acknowledge not only the fragile, but also the chanceful nature of this union.

Jessa Linger recently proposed the expression “politics of the leak” to discuss the political expediency of information that resists confinement. She writes, “perhaps we can use a politics of leaks to critique the perception of institutions as similarly whole and static, when in fact they are in flux and seeping.” Her expression may be equally applied to critique the imagined holism of “clean” data sets.

Thinking of data as something that leaks suggests that data are simultaneously excessive and incomplete, both “multiple” and “partial.” Over the past two decades, a wave of ethnographic work has invited readers to think of all manner of singularities, in the multiple. These authors do not write about digital data derived from mobile or wearable devices, but their work can offer useful correctives to images of crystalline and dynamic data flows popular today. A good example of this kind of theoretical intervention is Annemarie Mol’s ethnography, The Body Multiple. She challenges the coherence and singularity of “the body,” directing attention to the competing histories and experiences that shape fluid and variable notions of bodies.

Considering the limits of knowledge, James Clifford offers the idea that ethnographic work – another imagined whole – produces only “partial truths.” For Clifford, acknowledging that truth is always partial forces us to think beyond the standard idea that truth will be accessible when incomplete information is simply filled in. The researcher or author, then, is no longer authoritative, and knowledge is not ultimately cumulative, comprehensive, or objective. Instead, ethnographic knowledge is rendered from one specific, situated vantage, producing information that is by definition limited, variegated, personal, and incomplete.

These epistemological arguments are also slowly being made by data scientists. In fact, in a recent article, data scientists Tye Rattenbury argued that thinking about the social dimensions of data and data processing is not just a job reserved for the social scientist. He emphasized that “shining a bright light on the deepest lineage of data that impacts business or design decisions is important for everyone involved.”

Thinking of data as something that can be cleaned represents an idealized view of technology; it sanitizes technology from messy contingency and lived reality. What if digital data were more frequently represented the way journalists represent Chris’s boards? The chaos of images and souvenirs form an image of data that is both multiple and partial, constructing fractured narratives that explode and clot in surprising ways. We could also invite readers to view his digital data as inherently excessive, capable of making unplanned, surprise, or promiscuous connections, producing archives which are only ever partially complete. The “disarray” of Chris’ boards could help us model new thinking about digital data, rather than serve as their silent other.

Yuliya Grinberg is a cultural anthropologist exploring digital theory and practice at Columbia University. The idea that daily life overflows with data has become commonplace. Her research examines the history and the cultural logic that have made collecting copious digital records meaningful work. To learn more about Yuliya’s work, visit ygethnography.com

Yuliya Grinberg is a cultural anthropologist exploring digital theory and practice at Columbia University. The idea that daily life overflows with data has become commonplace. Her research examines the history and the cultural logic that have made collecting copious digital records meaningful work. To learn more about Yuliya’s work, visit ygethnography.com

Related

The Domestication of Data, Dawn Nafus

Reconsidering the Value of Wearables, Sakari Tamminen

What We Talk about when We Talk about Data, Brittany Fiore-Silfvast & Gina Neff

0 Comments