This paper assesses the economic impacts of hyper-monetization, immersive advertising, and general shifts in gaming’s fandom subcultures over the past decade. In unpacking notions of cultural authenticity from a branding and marketing perspective, I hope to point out further trends in the monetization of fandom and community that serve as engines of continued change and driving forces in the continued development of gaming culture. While much scholarly work is done on online spaces around gaming specifically, it is often focused on community experience; whereas in practice, questions being asked by companies are often how to make those communities more profitable customer bases. I want to use my experience in negotiating the desires of companies to advertise with the desire of communities to not exist in a capitalist hellscape to examine the friction between these paradigms and what it may mean for fan cultures moving forward. In the end I hope to question whose interests we as ethnographers serve in working in professional capacities alongside brands. Often serving in our classical capacity as infiltration specialists, those of us who pursue careers as practitioners often must reckon with the impacts of capitalism on the sectors in which we work. We too are subject to the same pressures as content creators and event organizers, while our passion may be educating and bringing clarity and understanding to help brands reach “authenticity”, we too become a part of this shift toward commodification of community. Eschewing the narrative of the heroic anthropologist, last bastion of community interest, I hope to call into question that against the seemingly ineffable force of capitalistic intent and the cultural change it begets, how can we still carve out a space for leisure and fandom that isn’t centered on monetization?

INTRODUCTION: ON GAMING, AUTHENTICITY, AND FRICTION

Authenticity is perhaps the most pursued and prized attribute in the realm of gaming events and conventions. Ever since Barbara Stern (1994) called for marketing scholars to consider authenticity in branding, it attained an almost cult-like fascination across industries.1 In the gaming events world, authenticity is closely associated with modes of immersive advertising or “activations” used to promote products at conventions and in online spaces. This paper will investigate the friction in the pursuit of authenticity that emerges from the competing goals of fans and for-profit companies. For fans, the purpose and attraction of a gaming event is often social, of sharing in the love of a common interest with a wider community and celebrating the things that catalyze fandom. On the other hand, for profit organizations often deter genuine social and cultural interactions by aggressively commodifying fan culture under the guise of authenticity because of their underlying emphasis on advancing profits over nurturing the community.

The resulting friction as it plays out in the material space of gaming events, conventions and culture is peculiar, spectacular and at times, self-contradictory.

Structurally, this paper is divided into five parts. The first section will develop our understanding of the concept of authenticity by drawing on theoretical discussions in tourism, art and gaming. The next section provides a brief history of conventions and fandom and a classification of different types of events that are foundational to gaming culture. The third section of the paper will delve into a concrete, well known example of corporate commodification successfully infiltrating fan culture via a material artifact—the gaming chair. Next, the paper will expose the internal contradictions and frictions that occur in the physical space of the convention, and it plays out during an event. The conclusion of this paper is a reflection on the role of the ethnographer, offering a provocation of how we might remediate this friction through our work.

OVERVIEW: AN AUTHENTIC DEFINITION OF AUTHENTICITY

What exactly is authenticity? As George E Newman (2019) argues, it’s important to remember that the idea of authenticity is a historical, domain and values-based construct that is often unstable. Even in the art world, for example, where authenticity is tied to the provenance of a work, this somewhat straightforward requirement can still get messy as in the case of performance art (Potter, 2010) or pop art Price (2007).

More relevant to the work in this paper is the definition of authenticity from the sector of tourism and cultural commodification. Cole (2007) points out that notions of cultural authenticity in tourism are often tied to commodification of culture for a eurocentric western audience. We can see this play out in mundane conversations in different categories—what counts as authentic food is probably the most common example where everyday people themselves wrestle with the concept. So why then do we find ourselves so enamored with the concept? Furthermore, why are marketers and companies seeking the veracity and perceived authority that accompanies authenticity?

There is a delicate balancing act with which event organizers and event companies, whose budgets for the most part come from presenting sponsors, engage. The relationship between sponsoring companies and the gaming communities they advertise to is inherently transactional and the attention of those communities is seen as a commodity. Making events bigger and better requires funding, but that also means more brand interest being catered to. And among different types of events there is a spectrum of manicured presentation that is mostly made possible by external sponsorship. This converts events to what Gee (2005) would call an affinity portal, a transactional space for marketing to a target community niche.

But there are also some inherent aspects to fandom that complicate the relationship between fans and corporations further. As Jenkins (2006) points out, modern notions of fandom are largely participatory in nature and the culture industry is one that lives and dies by fan engagement. This engagement and its invitation toward participation also encourages fans to become creators, contributors to the vast sea of “content” from which fandom emerges; and capitalism urges those producers to commodify their passion, to convert their production of content into a stage for “authentic” advertisement. An authenticity partly engineered by fans and partly by brands whose influence on these fans turned advertisers has repercussions on the general aesthetics of fandom at large.

While an argument can be made that media fandom is inherently consumerist, it is also generative and much of what we associate with “content creation” has its roots in hobbyism. Turk’s (2013) work on the gift economy in fandom highlights this in terms of art production. As fan works continue to exist, they are minimized by cultural subtext inherent to the growing idea that “content creation” should be monetized. Much like event organizers need sponsorship to make events happen, creators shift toward monetization of their fandom and passion as a way to justify the amount of labor put into their fan works.

Viewed through this lens, the notion of authenticity is much like the nostalgia associated with Walt Disney’s Main Street USA—a manufactured facsimile of something that once existed only in so far as it was imagined to exist. Both Main Street USA and market activations at events are what Baudrillard (1983) describes as a simulacrum. But in the same way that Main Street USA cannot truly capture the intimacy of small-town American living, large scale events often struggle to not feel corporate or to capture the intimate nature of a smaller fan gathering.

To truly understand the cycle of commodification and its entanglement with authenticity at fan events we have to go back to the beginning.

CONTEXT AND HISTORY: DON’T LOOK BACK YOU CAN NEVER GO BACK

Conventions associated with fandom trace their roots back to science fiction and literature fairs with the most notable example being the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention (WorldCon) in New York2. The convention, organized by science fiction literature fans and authors, was held in conjunction with the New York World’s Fair, aptly themed “The World of Tomorrow” and included some of the first examples of modern cosplay in the form of science fiction inspired costumes and outfits. Notably this World’s Fair would be formative to two industries that are both discussed in this article: the theme park business and the conventions business.

The first WorldCon was unique in that it was the first convention in the US to truly drew fans from across the country in larger numbers, fan meetups and gatherings of various literary societies had been occurring for most of the decade prior but nothing quite on the scale of WorldCon, which was also entirely organized, self-funded and operated as a bottom up, fan-based endeavor. The bottom up, fan-organized model was disrupted when corporate entities, who until the early 00s had mostly focused on trade shows, entered the equation. Trade shows had always existed in the games industry but tended to be closed events with limited press access and a focus on business and corporate showcases. Some trade shows would be open to the public usually for a day or two and would in some ways mimic the Worlds’ Fair mentality of showcasing future products to consumers. As companies who specialized in trade shows entered the space, it fundamentally altered the setup of conventions.

As it stands today there a few ways an event can be operated:

- Events managed by events companies which make up the largest portion of notable conventions.

- Events organized by nonprofit organizations like San Diego Comic-Con (SDCC)

- Events run by volunteer organizations or volunteer organizers such as WorldCon.

In all three cases, the corporate industry has taken up a key role in the realm of funding. Traditionally vendors could purchase booth space and a vendor could be anyone; a local book shop, an independent game developer, or in some cases large companies who want to interact with people at the show. But slowly over the course of decades, the exhibitor halls of most fan conventions came to look more like the expo hall of a trade show. The shift toward more corporate interest in fandom spaces is also present in other spaces, not just conventions (cons). For instance, if we examine the upsurge in corporate sponsorship of livestreamers and even the very marketing flavored rebrand of a wide and diverse array of online creative endeavors to simply “content creation” we can see the reduction of a wide variety of unique types of creative work and styles of video or livestream being produced, to a new type of vertical to advertise within.

But the entry of brands in a more profound way also suddenly led to the obsession with authenticity, an acknowledgement that the unique affordances and intimacy of these new media had a nuance to them that seemed more personal. This argument is multifaceted, not only presenting a marketing front that is meant to be naturalistic but also incredibly subtle—the definition of authenticity that emerges is “marketing so good, no one realizes it’s marketing.” This is a trend not unknown in the realm of online media, we saw it in the early days of YouTube when suddenly sponsors were cropping up in videos, Maker Studios and other companies began to emerge as talent agencies for the new job of “influencer.” This coincided with a realization in marketing that Millennials as an age set were leaving television and other traditional verticals to watch more niche content online.

Generationally the group of people who had grown up bombarded with near constant ad breaks on TV, billboards, popup ads on the internet had decided that content from people like them without ads was enjoyable or refreshing. Despite this migration, the nature of advertising is to go to where the people are and so we began again the cyclical process of what Cory Doctorow (2023) has called “Enshittification” or platforms that go from social spaces to marketplaces. Cat Valente (2022) covers this experience in her article’s title “Stop Talking to Each Other and Start Buying Things”. The notion that as a new form of communication and a new place for people to interact emerges it is as ever tainted by commodification in some form. Whether the excuse is “Well we have to keep the lights on” or “Servers aren’t cheap” or the classic “Nothing is free” eventually these often-free services, these digital locales designed for interaction between people of common interest fall to monetization. To quote Valente’s rather powerful summary of this effect: “Stop benefitting from the internet, it’s not for you to enjoy, it’s for us to use to extract money from you. Stop finding beauty and connection in the world, loneliness is more profitable and easier to control” (Valente, 2022). So, what then does all of this have to do with conventions? Events which, by their nature, bring people together physically.

The answer is a bit of a complex one, a cultural undercurrent of the whole endeavor of making community in the age of the modern internet. While communication has sped up the world of fandom from zines and letters to forums, web zones, and social media in all its myriad, this also creates a more defined footprint, a data trail increasing the visibility of passion and fandom. With visibility though comes spotlight and with spotlight exploitation. This is not to say at any point that running a fan gathering in person at a venue is a “free” thing, things cost money that’s a baseline within a capitalistic system. But if we look at the history of events many early conventions operated at a loss. As Klickstein(2022) highlights in his fantastic oral history of San Diego Comic-Con, it was years before the Con, which would become a sort of blueprint for modern Cons, was in the black financially.

While SDCC as an organization still operates as a nonprofit, this is no longer the case for a large number of the bigger conventions at least in the US. Whereas Comic-Con has grown to its current size over a period of decades, other events attempt to start at a size more comparable to SDCC and are able to do so with corporate investment. This creates somewhat of a divide, the corporate owned large scale shows that hire events companies and subcontractors to handle everything from registration and check-in to running whole areas of the expo hall make up the bulk of larger cons. Meanwhile many of the smaller, local conventions that get put on around the US and Canada only happen because of a dedicated volunteer committee devoting time to making a show happen, even if some are small businesses with some amount of full time staff. Thus, some of the biggest problems facing smaller events are organizer collapse or lack of funding and one of the biggest barriers to growth is acquiring sponsorship or the ability to pay for larger venues and grow. Meanwhile some of the largest, most iconic conventions such as Anime Expo, SDCC, and notably Japan’s Comic Market or Comiket all operate on not for profit models.

We live in an era of corporate consolidation however, and since the mid 2010s various larger trade show brands such as Reed-Elsevier Exhibitions (RELX) and Informa Connect, have been actively acquiring larger local conventions and fan events (Informa Connect, 2015; Gale, 2023). Important to note here is in this process smaller marketing firms or fan groups that support small businesses are being bought up by larger entities with an eye for larger clientele. A trend that mirrors some of the aspects of growth of a con itself. Therein lies the double-edged sword of growth, as events grow they lose the intimacy that founding members associate with the con. As more outside investment and corporate sponsorship moves in and priorities shift toward profitability of an event within a portfolio rather than one or two annual events occupying the full attention of an organization, there is sort of an inevitable loss of intimacy at a macro-scale that occurs. And for an event to remain at that size it depends on the money more from its sponsors and B2B interaction than simply ticket sales, which of course caused issues during the pandemic.

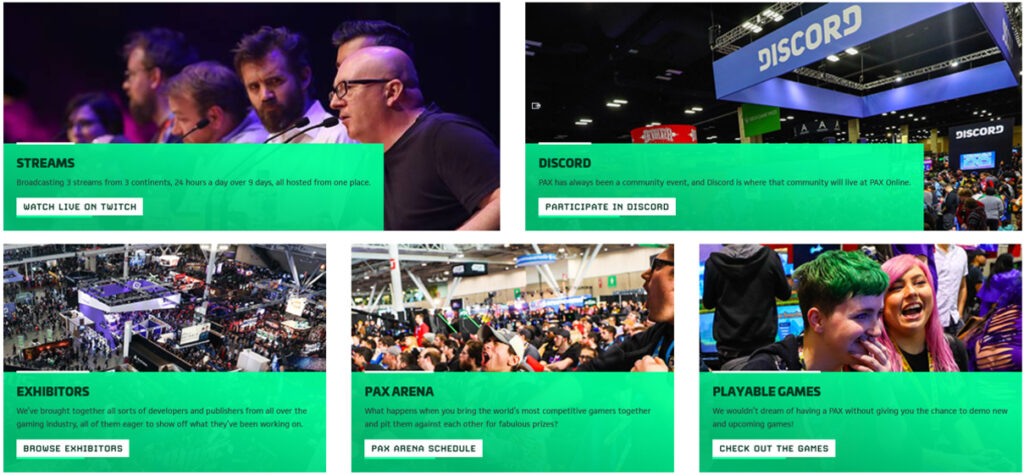

The pandemic era has been an interesting two years for this space. 2020 saw mass cancellations of events and a big move toward online events in lieu of in person cons (Woo, et al., 2022; Reed Exhibitions 2021). But online events did remove a particular element from the experience, the meeting other people and interactivity of an event. Many online events were prepacked video content, live streams with giveaways, discount codes for associated online vendors, etc. It truly was an exercise in attempting to reduce a largely nuanced and in person experience to a collection of panels, trailers, activations, and talks. In some cases, like PAX Online (Fig 1) and DreamHack Beyond (Fig 2) there were various attempts at simulation of the con floor experience.

The most important element of an in-person event is the feel of fans being able to directly interact with the industry and each other, and in the case of these digital events that was widely lost. One of the main goals of course, was to make good on promises to brands and sponsors, many of whom had pulled out of events for fear of being associated with an event where an outbreak might occur. This meant numbers and metrics became key to the two years of “online only” between 2020 and early 2022 with an aim to measure the “reach” and “impact” of a sponsorship, but when left to pure numbers, the results in some cases were less than ideal. Fast forward to late 2022 and into 2023 and the return of live events was a rocky one at least internally which shifted the focus once again to making sure events could be funded and turn a profit.

So let us now turn to the matter at hand, the question of authenticity within this world of fandom around gaming and events.

CONFLICT: CHAIRS FOR PEOPLE WHO DON’T SIT

To discuss the notion of authenticity through the corporate lens we have to understand how companies see the wider gaming community. So, let’s talk a bit about the ways that “gamers” have been referenced in my own experience. Fairly early on in my career, I was in a meeting where investors in various esports companies were discussing the industry and a phrase that will stick in my mind forever floated through the conversation “Wealthy Millennials”. Bearing in mind that this was at the same time that articles bemoaned millennials not spending money, not buying houses, living with their parents; the problems and economic pressures on a generation beset by student debt and simply not engaging enough with traditional notions of economy3. And yet, in this meeting these people were convinced that the wealthy millennials were the gamers because they “had a higher index of discretionary spend on their hobbies” based solely on credit card data.

The term was not only uncomfortably oxymoronic but made an assumption of a mostly semi-affluent, mostly white, and mostly male demographic of “gamers” which is a myth still being unpacked in the wider industry. Volumes of work have been compiled on the subjects of diversity and the nuanced visibility and invisibility of race in fandom and gaming, the edited collection Fandom, Now in Color (2020), and works like Intersectional Tech: Black Users in Digital Gaming (2020) do a great job of discussing these topics in more depth and nuance, but the core of the problem does still remain. A base assumption that the gaming community is mostly white, mostly college-aged, and mostly male. But it doesn’t always end there, there is a pretty rampant reductionism and practice of what I like to call “invent a guy” methodology.

Non-research based marketing personas can be a dangerous thing, often riddled with biases, and gaming has not been spared this practice by any means. The notion of what a gamer is has changed monumentally in the past decade at least for those within the wider community. In practice, we have seen greater diversity, inclusion, and visibility at events, a wider age range that continues to expand, and a wider audience in general still subdivided into a million overlapping subcultures with interests that intersect and connect in highly individual ways. The core disconnect is that in many cases, companies (outside of specific marketing efforts to, for instance, target women in gaming, or target fighting games tournaments for “diversity”) have tended toward that idea of a white 20-something male. They invented a guy, and in more recent years invented a more gender amorphous gamer construct and have stuck to it.

A prime example of this has been the evolution of gaming “gear”, which coincides largely with the explosion in livestreamers. Tim Rogers of ActionButton explained this concept beautifully in his review of Cyberpunk 2077 (2021). In that review, Rogers charted the rise to ubiquity of “gamer chairs” styled after race car seats. The core of the argument is that people who play games, from a hobbyism perspective, had “famously put up with bad hobbying conditions” to the point of memes communicating as much (Figure 3).

The iconic image of wood paneled basement and an old dining room chair with a CRT playing Demon’s Souls has been passed around innumerable times online. The image itself is sort of a nod to a communal experience of a generation and one that has come up in interviews time and time again of what things were like before. When I interview people about the evolution of their PC gaming setup those who are in their late 20s and older (including the aforementioned Millennials) they often talk about a time before gaming chairs, when an Office Depot chair was a luxury and when some assemblage of a sideboard, a desk not meant for several monitors, or the wonderful late 90s computer hutch was the setup. So, what changed?

Gaming chairs were part of the invention of “the guy” in gaming, the rebranding of cool and slick with lots of RGB lighting. The first gaming chairs were commercially released in 2006 and almost immediately were highly visible. Rogers (2021) points out that chair companies almost immediately began sending chairs to streamers and youtubers. For many this was probably the first decent chair they owned so in going from a cheap folding chair or office chair to something that felt markedly nicer it became easy to naturally promote. To quote Rogers:

“After enough influencers saying enough times… ‘Guys, I LOVE my new chair’… After you see that $400 price tag enough times, your brain plays a trick: You think, that’s how much a chair costs.”

(Rogers, 2021)

By creating necessity, by increasing visibility of something to such a degree of cultural penetration that an audience simply believes “I need a gaming chair because I mostly play games at my desk”, marketers planted the idea of yet one more piece of the gaming setup. And this happened over and over: PC cases with RGB lighting, Razer’s iconic bright green headphones, mechanical keyboards, suddenly there was an explosion of “gamer” branded items that had reached a level of cultural association that a “real” gamer setup had to include them. By way of complex immersive marketing of multiple products, companies codified what an “authentic” gaming setup needed to look like.

In interviews and photo studies I’ve conducted for clients over the years I often ask participants if they have photos of LAN Parties or past events they had gone to, you do begin to see the origins of some of these trends. In the 1990s looking at images of builds done by professional PC builders, hobbyists, and industry professionals we see a lot more UV lights with specially treated internal parts that react to UV present inside of PC cases. However in the 90s and 2000s you also saw a good amount of cases and towers, even for custom built PCs, that were relatively low profile, similar to a standard Gateway, or Dell gray or black tower cases some may remember. The UV style lighting went out of fashion sometime after 2014 when both Razer and Corsair unveiled the more modern RGB LED products that we see in a lot of “gaming” computers today.

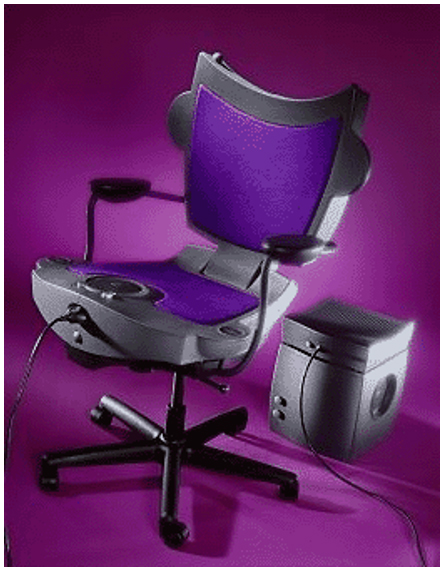

These shifts are sometimes matters of trend forecasting, in others like in keyboards it was first a push toward quality design for the discerning consumer pulling from the fringes of home built mechanical keyboards into more commonly available consumer models, and yet still in others it is a case of seeing a void, there really weren’t “gamer” chairs for a long time outside of incredibly niche products, the brands of which have been all but forgotten by people who can show you a picture of the setup and say “My dad got this for Christmas one year, it wasn’t particularly comfortable and it had speakers mounted in the headrest so you couldn’t actually move it too far from the desk” (Figure 4).4 By the 2010s it was a foregone conclusion that a “nice” gaming setup also featured a nice chair. More often than not, said chair was the aforementioned race car inspired design.

The connection here, where it all comes back into line with the idea of events, is that oftentimes those events are venues for marketing. Both LED PC cases, and gaming chairs made their debut at CES (The Consumer Electronics show), and gaming chair companies heavily sponsored early esports leagues. Gaming chair companies would thus feature prominently at conventions, especially more gaming focused ones with a LAN party5 component and either sell off chairs that were provided to the event to avoid shipping them back or give them to event volunteers who lived in the area to save on shipping. Hardware companies would create gaming sub brands such as Dell’s Alienware, Asus’ Republic of Gamers (ROG), or HP’s HyperX to name a few. Whereas CES is mostly a trade show, meeting customers where they are necessitated presence at fan events and cons. More and more often large corporate booths dominate expo halls, prominently branded sponsored equipment appears on stage, in freeplay gaming areas, and at booths offering a “try before you buy” experience baked into the wider event. But this doesn’t extend to just products aimed at a gaming or fan audience specifically, everything from car insurance, to large media brands want to be present and visible at the various gaming and pop culture conventions. Their presence is mostly a pretense to reach a demographic that so readily spurned traditional advertising, and to participate in driving cultural norms by way of dictating what the next thing in “real” gaming aesthetics is.

DISCUSSION: MANUFACTURED AUTHENTICITY, COMMODIFIED FUN

With that being the case the brand side is often more concerned with a microcosm of their own activities, like that first World’s Fair but on a smaller scale, some amount of theme park design goes into making a good booth. In a majority of cases larger brands may hire ad agencies or marketing firms to design their booth but the experience itself is often designed in a vacuum, and often under the misconception that a booth will be the cornerstone of an event experience.

Meanwhile for smaller booths, indie devs, etc the most they may design is a banner with the title of their game, maybe a few cardboard standees knowing that they are one of many creators present at the event (Fig 5). Between this and the general nature of convention centers as blank slates, different events can often feel eerily similar when you view the expo hall from above. Sure, there may be idiosyncrasies of different venues, convention centers, stadiums, etc, but the idea of replicability also bakes into the “authentic” experience. From an attendee standpoint it is pretty great if they, as many do, only really go to one or two cons a year that are close to home for easier and more affordable travel. This pushes events to be like other events and creates a ripple effect of standardization.

Much like any business franchise, this sort of homogeneity of the basic elements of an event promises patrons the somewhat magical experience of consistency. No matter where you are there will be a con that will be just like the con in that other city you’ve always wanted to attend. And corporate backing makes sure that event is funded and has vendors signed on for year long contracts and multi-event booth agreements so that it will truly feel the same in a lot of ways. Some vendors who set up booths to sell things like mystery blind boxes6 or other more general merch booths may even make a seasonal job out of working the convention circuit. This kind of deal also works well for small businesses that specialize in more niche products such as custom game controller brands. But with this similar feeling backdrop what then becomes of the authenticity of an event? Well to a large degree the authenticity is in the replicability, the sort of sameness of the backdrop for the event itself, the consistency, and the ideal of striving toward being the best possible version of all the various local and small shows over the years. Much like Main Street USA it can begin to, for the experienced attendee or for those in the events business, elicit a strange experience of something all at once being its own entity but with all the intent exposed, a simulacra that knows exactly what it is supposed to be in concept and has truly smoothed out all the edges. So if we consider the con, the show, the expo hall and all its components to be the backdrop for experiences, what then is the answer to the question of creating an “authentic activation” for a brand? When the expectation of the attendee is much the same as at a market, art fair, or festival, browsing or having a brief interaction with as many or as few things as they may want. When interviewing attendees of events and asking about what they want to see at the event the majority respond with two or three things, or in the case of a group of friends attending together one or two things they each want to see or experience and the rest is exploratory the sort of classic “well of course we want to check out the booths and see what there is to see” response in its many variations. Booths, while eye-catching and often serving as a sort of anchor of operations for a brand at a show, may be less interactive in some cases and this is where the idea of “immersive” activations comes into play.

Sponsorship activations are agreements wherein a sponsoring entity, in this case let’s say a PC manufacturer, makes an agreement with an event to have a presence at said event. Most commonly people think of booths or panels or even just throwing money at making a tournament happen, but with some finessing there are more naturalistic ways for sponsors to activate in ways that make sense. When pursuing an “authentic” activation one of the key questions to begin with is where can a brand actively facilitate the rest of the experience happening at the show? For our aforementioned PC manufacturer the answer is obvious when it comes to gaming shows, simply provide all the PCs needed for the event. More often than not this will include PCs used on stage for tournaments or may feature a “Freeplay” area where gaming PCs are set up and preloaded with games for attendees to sit and play with friends or just to take a rest from walking around a convention center. But at an event where the main focus is gaming or event that may only have gaming as one of many subgenres present this sort of involvement does two things: first it’s for the most part sans some pretty normal sign placement somewhat unobtrusive, it doesn’t feel like this is PC Manufacturer con now it just feels like another thing that happens to be at the event. Secondly, this gives attendees more hands-on interaction with the thing being sold, and the number of times I have observed people leave one of these areas and ask a staff member what kind of PC, or keyboard, or headset was used at the Freeplay is not insignificant. The authenticity of the interaction is in that exchange, in a non pressure environment you are able to try a product, no one is trying to actively convince you to purchase it or even throwing a logo in your face it just exists as texture to the rest of the convention experience. However, the context is also key here because it can define intent.

The nuance of all of this is the difference in how an event may feel to people attending it and striking the balance between something that feels community first and community driven while still giving plenty of space and share of voice to sponsors is a delicate process. Event organizers, usually smaller teams within these much larger events companies or within larger corporations that put on their own events tend to define the way that balance looks and feels. Businesses rely on the engagement of fans as a metric of success, the number of images shared on social media, number of retweets on the sponsored giveaway, or meticulously calculating foot traffic through a booth to quantify success. Meanwhile for those closest to the event in its actual execution there is a real sense of creating the best possible experience for attendees. Things can get strange, when a brand gets too hands on, especially a “non-endemic” brand7. Non-endemics are a much more difficult proposition in that regard and are often where an event can start to feel a bit overly corporatized. Up to this point in our example I have presented mostly theoretical examples of more endemic brands, for a PC manufacturer it is an easy fit to find some way to help out at an event and mesh into the wider fabric of the co, but non-endemic brands tend to have issues.

For instance at a gaming convention you scan the sea of booths and areas often marked off with simple pipe and drape barriers only to see an entire quadrant of the convention center plastered in the logo of a spice company. Where most other booths are designed to sort of fit in, darker color palettes, sleek construction, the spice company has just launched its summer marketing campaign, their marketing department insisted they stick to brand guidelines for the campaign. The area is carpeted in astro turf and a decidedly bright yellow color scheme. In an effort for “authenticity” the organizers have pushed this brand into sponsoring an area where people can walk up and play games, but the brand required that every PC monitor be topped with a sign reading “brought to you exclusively by spice”. This is increasingly common. The desire of the sponsor is to extract value and ROI from the event by way of advertising and reaching a demographic or subgroup that it often has trouble marketing directly to – the event company selling the event as an affinity portal to once again reach the “Wealthy Millennial”, or increasingly the “Zoomer” demographic.

The goals of the individuals organizing the event from a corporate standpoint may be to put on a good show that serves their community, the overarching goal of the parent organization is ever expanding profit as is the nature of a for profit venture. But the ability to sell to those larger brands hinges on fans having fun and wanting to come to your event. And so in much the same way as the gamer chair word of mouth spread from streamers, so to does the enthusiasm of attendees, the week long social media feed within fandoms where you will probably see at least one person if not more posting from a large event plants the seed that maybe that small local convention you have been going to isn’t enough that you need to make the pilgrimage to the bigger, better, branded event. This of course mimics the reverence held for something like a San Diego Comic-Con or Anime Expo within fandom, the idea of wanting to go to “the original” event, the one specific to your interest. And in the spirit of that many corporate entities and events companies have gone about acquiring successful events to then grow them and make them ideal affinity portals to brands. This happened a lot during the pandemic, the financial pressure put on nonprofits and small organizations by not having an in person event for two years created an opportunity for the larger corporate entities to bail the smaller shows out, often still featuring said non-profits as featured partners or consultants (Gale 2023). This also of course in the reboot post pandemic did result in the closure of some “underperforming” events in the corporate catalogs. With profit as a motivator it becomes much more than just the “break even” mentality of nonprofit organizations or smaller shows to an ideal of maximizing profits which often means selling the audience, sound familiar?

CONCLUSION: WHOSE INTERESTS DO WE SERVE?

As practitioners whose business it is to know culture and to guide others in understanding it, it is important to understand what the knowledge we are producing is being used for. Oftentimes the key questions from clients in pursuing any affinity portal can be summarized as “how do I fit in with this group, how do I make them like me?” but the intent, the directive from above is “how can I extract value from this new thing I don’t understand?” It is never really about understanding the people at an event or the event itself, it is about moving into unclaimed territory to find new riches. That is why the pursuit of authenticity in marketing has always confused me and has remained something I push back against. Because authenticity is the furthest thing from what brands strive for in reality.

In some cases, authenticity means actively shaping the culture, in others it means owning the venue where cultural events occur and by extension owning the audience as a commodity to be sold. More than anything, authenticity exists as a way to romanticize the notion of driving consumerism but in a “fun and naturalistic way”. Yet the term has dominated the vernacular of marketing especially in spaces that touch the digital. We can consider the cult of authenticity as the pursuit of control of the narrative, dictation of culture and practice in much the same way as “gamer” aesthetics and branding still dominate the home PC space. Many variations have since emerged to meet different niches and aesthetic sensibilities; but the baseline was set by brands filling a space that had not been fully codified with an authentic article. Manufacturing this kind of authenticity is easier than ever as influencer culture pressures individuals to monetize every interaction as we reduce writing, art, video, and even games to “content” to be commodified with more space to put yet more ads. But, much like the conventions and events discussed here, human interactions keep happening. To quote a participant in a study about the way a booth was designed, “I dunno, I’m mostly here to hang out with my friends, so I wasn’t really paying attention to every booth…” Despite the capitalist hellscape we live in where companies are always trying to sell people something or finding new ways to monetize our existence, we can forget that the bits and pieces of a given culture that make it so appealing to commodify for brands are the pieces that don’t need brand influence to function. Alongside every expensive gamer chair are still the folding chairs, office chairs, and dining room chairs. Beside every corporate megabooth there are small indie booths, you can still find small local conventions run by nonprofits, despite the corporate shows being more visible. At either end of that spectrum the purpose of the event is still bringing people together in a common interest.

In reality authenticity is something felt by individuals in an interaction and in the case of fandom, for better or for worse it is a feeling of legitimacy within the space. A company can throw as much advertising as they want at something only to have it ridiculed online, a spectacle meant to impress in an expo hall may just end up with people rolling their eyes. But to one degree or another to those who only care about the level of engagement that thing is getting the PT Barnum adage holds true, any press is good press. What we can hope to accomplish as ethnographers, is to plant a seed of legitimate interest in something with our stakeholders. An interest that goes beyond simply “how do I get these people to pay me” and truly brings someone around to the paradigm of “how do I help out and not make this about me?” And when that idea takes hold, nothing could be more authentic.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Logan McLaughlin Is a digital anthropologist specializing in gaming, online communities, and the overlap between our digital selves and how we live offline. She primarily works as a consultant offering her expertise, skills, and research acumen to companies and organizations to help them better understand and interact with subcultures and communities. logan.mclaughlin@spacetime.gg

NOTES

To my wife Bailey for encouraging me to finally publish something. Thanks, are also due to Gary Briggs and the team at SpaceTime Strategies for giving me the opportunity to submit my research for publication. Finally acknowledgements are also due to the many video essayists, internet archivists, and commentators who document the history of the internet, its cultures, and specific moments in time for inspiring this work.

1. Barbara Stern was a professor of Marketing at Rutgers University known for making a career of firsts in the market research world. Her work was often defined by a usage of literary criticism in consumer behavior and advertising that drastically shifted paradigms in her field. More info at https://www.gc.cuny.edu/news/proud-be-first-barbara-b-stern-was-first-woman-receive-doctorate-graduate-center

2. For more on WorldCon there is a good bit of scattered history including the original NY Times Article (https://web.archive.org/web/20110312100633/http:/www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,761661-2,00.html) Covering the con as well as a few issues of the Fanzine Mimosa (http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m29/kyle.htm, https://web.archive.org/web/20080401064731/http:/jophan.org/mimosa/m21/kyle.htm) which has the unique position of hosting quite a few people with direct connections to the event. Andrew Liptak’s Cosplay: A History covers some of the elements of costuming at the event. Cited in this work the fantastic oral history collected by Mathew Klickstein See You At San Diego: An Oral History of Comic-Con, Fandom, and the Triumph of Geek Culture also touches in depth on that first WorldCon.

3. These articles cropped up everywhere in the period of 2015-2018 including the infamous Avocado Toast Article: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/food/wp/2017/05/15/dont-mess-with-millennials-avocado-toast-the-internet-fires-back-at-a-millionaire/ Articles on student loan debt: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-07-17/student-debt-is-hurting-millennial-homeownership The Economy: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/12/stop-blaming-millennials-killing-economy/577408/

4. A Full review of this chair can be found at: http://www.atpm.com/5.03/intensor.shtml preserved in perfect integrity, the reviewer reports “The chair also tends to build up a lot of static electricity. My fiancée refuses to kiss me while I am sitting on the chair because she gets a very strong buzz every time. The worst part about the chair is its comfort. I had horrible back pain after the first two days of using it.”

5. LAN (Local Area Network) Parties are a type of play involving multiple computers set up in one location on a local network thus requiring copresence, venues have included and still do include basements, garages, dining rooms, and whole convention centers.

6. Blind boxes are boxes full of miscellaneous gaming or pop culture related merchandise often purchased for a flat price but having varying qualities of goods inside.

7. Within fandom and gaming spaces, non-endemic brand is the term widely used in industry to refer to brands that don’t necessarily have a good reason to be at an event other than for marketing purposes.

References Cited

Baudrillard, Jean. 1988. “Simulacra and Simulations.” In Jean Baudrillard, Selected Writings, edited by Mark Poster, 166–84. Stanford University Press.

Campbell, John Edward. 2008. Virtually Home: The Commodification of Community in Cyberspace. Dissertation.

Chvatik, Daniel. 1999. “ATPM 5.03 – Review: Intensor.” Www.atpm.com. March 1999. http://www.atpm.com/5.03/intensor.shtml.

Cole, Stroma. 2007. “Beyond Authenticity and Commodification.” Annals of Tourism Research 34 (4): 943–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.05.004.

DreamHack. 2021. “DreamHack beyond 2021 Official Trailer.” Www.youtube.com. May 20, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9rOyf-HaVdY&t=64s.

Gale, Casey. 2023. “Acquisition of a Fan Expo Opens Doors for Nonprofit.” PCMA. January 31, 2023. https://www.pcma.org/acquisition-fan-expo-opens-doors-pop-culture-classroom/.

Gee, James Paul. 2005. “Semiotic Social Spaces and Affinity Spaces: from The Age of Mythology to Today’s Schools.” Chapter. In Beyond Communities of Practice: Language Power and Social Context, edited by David Barton and Karin Tusting, 214–32. Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511610554.012.

Gray, Kishonna L. 2020. Intersectional Tech. LSU Press.

Grinnell College. 2009. “Fandom and Participatory Culture – Subcultures and Sociology.” Grinnell.edu. 2009. https://haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/subcultural-theory-and-theorists/fandom-and-participatory-culture.

Informa Connect. 2015. “Informa Exhibitions Expands Pop Culture Convention Portfolio with MegaCon Orlando .” Informa.com. April 9, 2015. https://www.informa.com/media/press-releases-news/latest-news/informa-exhibitions-expands-pop-culture-convention-portfolio-with-megacon-orlando-/.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006a. Convergence Culture : Where Old and New Media Collide. New York ; London: New York University Press.

———. 2006b. Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers : Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Newman, George E. 2019. “The Psychology of Authenticity.” Review of General Psychology 23 (1): 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000158.

Potter, Andrew. 2010. The Authenticity Hoax : How We Get Lost Finding Ourselves. Toronto: Emblem Editions.

PRICE, SALLY. 2007. “Into the Mainstream: Shifting Authenticities in Art.” American Ethnologist 34 (4): 603–20. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2007.34.4.603.

Reed Exhibitions. 2021. “Reed Exhibitions Unveils New Brand Identity and Positioning | RX.” Rxglobal.com. October 6, 2021. https://rxglobal.com/reed-exhibitions-unveils-new-brand-identity-and-positioning.

Rogers, Tim. 2021. “Story #6: Season of Trash ACTION BUTTON REVIEWS Cyberpunk 2077.” Www.youtube.com. 2021. https://youtu.be/0k-zYGhYDGo.

SalsaShark. 2014. Wooden Gaming Room with Dining Chair and Demon Souls. Neogaf Forums. https://www.neogaf.com/threads/show-us-your-gaming-setup-2014-edition.745183/.

Södergren, Jonatan. 2021. “Brand Authenticity: 25 Years of Research.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (4): 645–63.

Stern, Barbara. 1994. “Authenticity and the Textual Persona: Postmodern Paradoxes in Advertising Narrative.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 11 (4): 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(94)90014-0.

Turk, Tisha. 2013. “Fan Work: Labor, Worth, and Participation in Fandom’s Gift Economy.” Transformative Works and Cultures 15 (August). https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2014.0518.

Woo, Benjamin, Emma Francis, and Kalervo Sinervo. 2022. “Framing the Covid-19 Pandemic’s Impacts on Fan Conventions.” Transformative Works and Cultures 38 (September). https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2022.2323.