Sociality

No human behavior exists in isolation. This collection demonstrates the core value of ethnography in understanding and activating people, products, services, organizations, and research itself as social phenomena.Overview

Ethnography’s success in industry is often attributed to its ability to capture the details of human practice, helping firms discover some unarticulated need or value that results in better design or market fit. This orientation, which has become most closely associated with “user studies,” tends to render people as individuals, interacting with a product in relative isolation.

As the papers in this collection argue, this approach is incomplete, and potentially even a kind of trap. It ignores the fact that we humans are fundamentally social beings. Our natural environments are other people – families, teams, communities, institutions, and societies. We cooperate, share ideas, influence each other, place demands on each other, and navigate these demands and influences in various ways. We rarely if ever use products in social isolation, and our economic activities – including our purchase decisions – are often essentially social.

The theme of the first EPIC conference in 2005 was sociality, establishing this concept as a foundation of our community and ethnographic practice. I noted the importance of this awareness in my own work in an EPIC presentation in 2007. Studying the messy, complex social systems in which we are all embedded is a lot of work, but it improves the value we deliver to our clients. I believe it also provides us with an opportunity to collaborate with each other more directly, and deliver value to the world beyond our individual projects.

Looking back through two decades of EPIC work, it is impossible to include all the important contributions that EPIC members have made on this topic, or the many ways sociality plays out across a vast range of circumstances and contexts. In this collection I’ve highlighted key pieces that either illustrate the importance of sociality, or explore the consequences of this perspective for our work.

Key Articles

Putting the ‘Social’ Back in ‘Social Science’ Research, Mikkel Krenchel (2021). This short piece clearly articulates the tension at the heart of this collection. Its very existence also suggests we as a community may still have a ways to go in addressing sociality. It provides practical advice for practitioners on how to begin to do so: by focusing on ecologies instead of individuals, thinking in terms of sample depth rather than sample size, and focusing on what people do together.

Social Relationships in the Modern Tribe: Product Selection as Symbolic Markers, Dan Bruner (2005). I include this paper because of its historical interest (the very first EPIC conference!) and the beauty of its ironic juxtaposition of the two approaches mentioned above. It reports on a study of how workers choose their work clothing, noting how preferences are shaped by what other (often influential) workers at a site have chosen, tried and found useful, or what groups have adopted as emblematic of their collective identity. This resulted in a high likelihood of consistency among brands or styles of clothing of workers at a given work site. Yet, when asked, individual workers were likely to express their preferences in terms of specific features of performance – e.g., the fit or durability of different brands of blue jeans – resulting in identical (and obviously directly contradictory) claims from one site to another about which brand is better. For me, this is a beautiful, classic rebuttal of the idea of focusing too heavily on the personal “jobs to be done” in our approach to ethnography, and the importance of social relationships, shared experience and influence, even for seemingly simple, utilitarian purchase decisions.

Skillful Strategy, Artful Navigation & Necessary Wrangling, Suzanne Thomas and Tony Salvador (2006). This is my favorite paper in the collection – partly because it is written by two beloved former colleagues, one of whom we lost in 2022 to cancer, both masters of their craft. But more importantly, because the authors do more than argue that we should get beyond the individual to take “collectives” seriously: they actually explore in depth how to do that, both methodologically and analytically. Their story of an intimate interview that suddenly became a group of 30 or more men all speaking at once (talk about “the cackle of communities”!) is by itself worth the read. How they ultimately turned this into a method is terrific. They also look at the challenge of representing ecosystems to their colleagues (“We described an ecosystem. They just wanted the next step…”), and touch upon how individuals across diverse settings skillfully navigate both societal power structures and local social obligations.

Myths and Facts about the Sharing Economy Promise in Emergent Countries, Nora Morales (2021). This wonderful PechaKucha explores the real market opportunity in emerging economies – helping people create economic value together, in ways that are often entirely surprising to those working for global corporations.

Framed by Experience: From User Experience to Strategic Incitement, Arvind Venkataramani and Christopher Avery (2012). This paper goes beyond methodological discussions to challenge a foundational aspect of the work of EPIC members – our ways of knowing and the purposes to which those are applied. As with other papers it sets up the same basic tension, but takes it in an interesting new direction, enjoining practitioners to go beyond descriptions and embrace both the art of problematizing, and the practice of advocacy, to help push their organizations beyond product innovation to genuine social change; what they call “strategic incitement.”

Go Deeper

Who We Talk about When We Talk about Users, Kris Cohen (2005). This foundational paper reminds us that what we investigate, and who we define as our “user,” are closely interconnected and often chosen on the basis of logics that clearly beg for critical investigation.

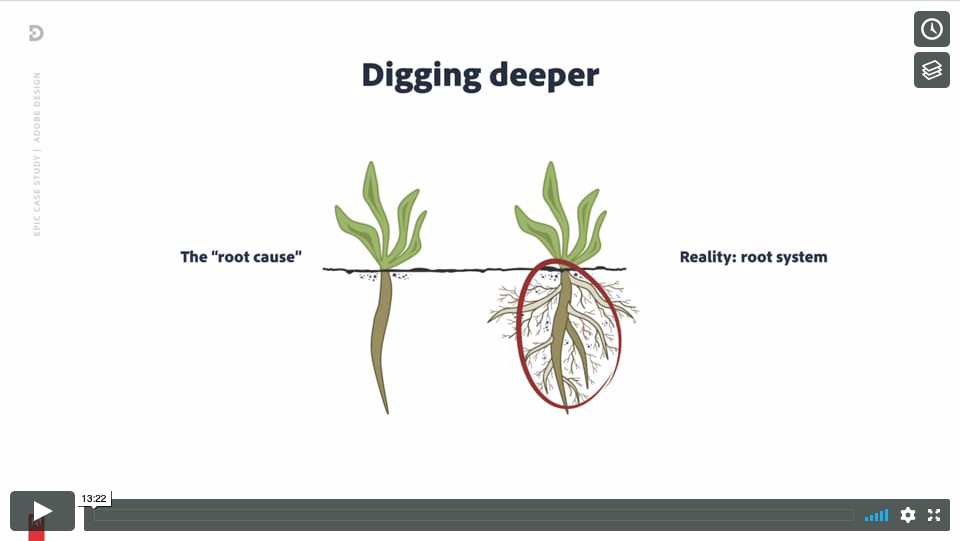

The Root Cause is Capitalism… and Patriarchy, Lindsey Wallace and Jenna Melnyk (2018). This case study captures how social forces from above and below affect work, tool use, and many other things “user research” traditionally takes interest in. In this case, a drive to “do more with less” at a software firm forces informal care work onto the shoulders of women in management roles. It is a pointed illustration of sociality’s negative dimensions.

Ethnography and Process Change in Organizations: Methodological Challenges in a Cross-cultural, Bilingual, Geographically Distributed Corporate Project, Elizabeth Churchill and Jack Whalen (2005). This paper focuses on the sociality of ethnographic research teams themselves, specifically teams engaged in process (rather than product) innovation. Nice discussion of how access, technology and practice can support or inhibit the alignment of members of the (large) research team.

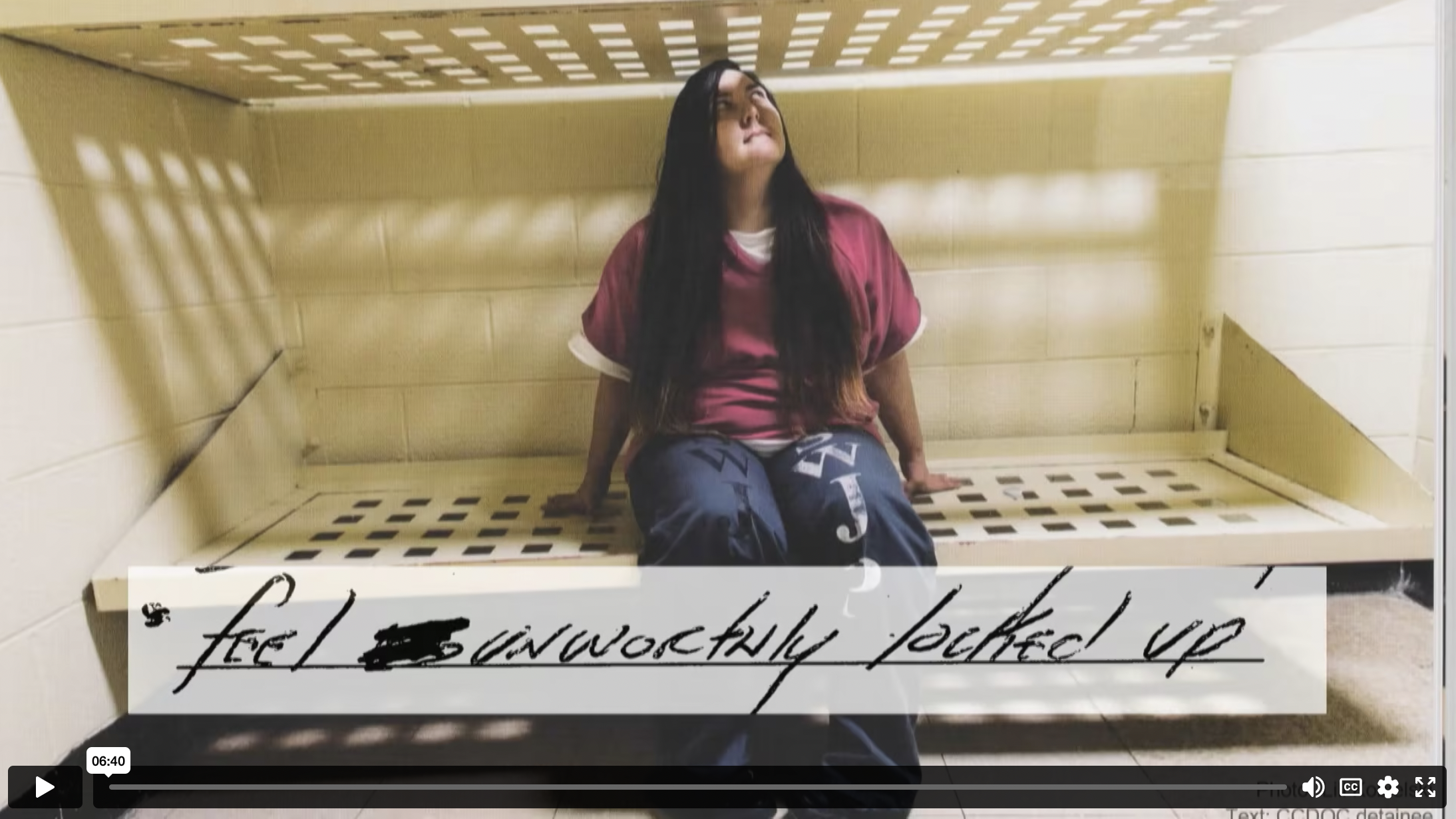

Social Resilience: Shifting from an Individual to a Shared Social Model for Building Resilience, Jenny Rabodzeenko and Kelly Costello (2022). ‘Resilient’ is often used to mean a heroic quality of individuals who overcome adversity. But as this PechaKucha shows in a US context, the concept of resilience can also allow us to abdicate social responsibility for the systemic causes of adversity, at the expense of disempowered people who struggle through them alone. The authors offer principles for social resilience, and a call to action.

Curator: John W. Sherry

Contributor: Elizabeth Anderson-Kempe