Case Study—This case demonstrates the power of video as a data collection tool and a storytelling approach to the presentation of research findings. Fresh Produce Clothing specifically selected Bad Babysitter as a consulting partner for their expertise in video-based ethnography and narrative style of delivery. The case begins with contextualizing a business with an imperative to evolve and an organizational culture that was not aligned. The locus of the debate was the Plus Sized shopper – a consumer segment that put interpretation of hard data by headquarters at odds with impassioned anecdotal inputs from the field. Video offered a visceral way to get past conjecture and “bring her into the room”. The primary benefit to the brand was the immediacy for translating learning into actionable insights and consensus on the way forward. The revenue impact was dramatic: leadership took a 180-degree turn from phasing the Plus shopper out to investing in her.

BACKDROP AND BUSINESS CONTEXT

Fresh Produce is a women’s clothing brand with a devoted base of shoppers who enthusiastically embrace the brand hallmarks of relaxed fit, effortless style, and bright coastal motifs. At the time of this study, their casual wear was sold online, through select retail partners, and in approximately 30 company-owned brick and mortar stores scattered across the Southern U.S. in warm weather climes and warm weather destination cities.

The company was founded in the late 1980s by a young man and wife team who struck gold with an impromptu idea to sell brightly colored T-Shirts on the streets of Los Angeles during the 1980 Olympic Games being staged there. The instant success of their designs compelled them to start a legitimate wholesale business designing and selling T-Shirts to independent tourist shops in coastal towns. T-Shirts led to shorts. Shorts led to skirts. Skirts led to dresses. And so on.

The wife, who had studied fashion design, decided to take over the business and build a retail brand. She moved the business operations to Boulder, CO but retained much of the manufacturing in downtown Los Angeles. Fresh Produce was conceived as a women’s brand with the vision “to lend style, inspire confidence and add color to our customer’s lives”. To this day, the tagline “Live life. Enjoy Color” remains as the calling card for the brand. The name Fresh Produce was created as a visual reference to vibrant color as well as to imply an ever-changing inventory.

The roots of the company proved to be a major business challenge as Fresh Produce sought to expand its direct retail presence. The company culture was shaped from the wholesale business where sales projections were based on orders placed by the tourist shops. Equally, the tourist shops represented a very uneven revenue stream due to the extreme seasonality of resort business in the towns where shoppers were used to finding Fresh Produce. The business had been built on “snowbirds” who come from the North for warm weather during winter months. Every year they would return and stock up on an entire Fresh Produce wardrobe.

Shortly before this study, the woman who founded the company decided she was ready to retire and wanted to sell. She had grown Fresh Produce into a $38M business with a devoted following of snowbirds and locals who spoke rapturously online about the clothing (these women are affectionately referred to as “Freshies”). Add to this, there was also a fairly devoted base of Fresh Produce store staff that supported brand equities around being a joyful and approachable place where women were celebrated. These dimensions bore out as important brand attributes in previous primary brand research.

Early discussions with investors revealed three concerns that were hampering the sale price of the company despite the brand being so beloved:

- Due to the “snowbird” shopper, the core consumer segment was women aged 45-64. Investors were concerned about what the long-term growth strategy would be once these shoppers quite literally “aged out”.

- The extreme seasonality was problematic. Investors wanted to see efforts made to adjust the assortment for a more traditional four-season retail revenue stream.

- There was still too much reliance on wholesale business (approximately 65% of sales). Investors wanted to see the direct retail business eclipse wholesale numbers.

Each of these concerns demanded leadership talent that did not exist at Fresh Produce. As a result, a CEO was hired as a bit of a growth hacker to find new revenue, streamline financials, and improve the sale price. A new CMO was hired to cultivate a new/younger shopper and to get the e-commerce and digital content game up to par with other national women’s sportswear brands.

At the time of their arrival in 2013, a modest revenue stream was coming from a handful of styles produced in Plus sizes that were haphazardly available. Depending on the manufacturer, most styles would arrive in only straight-sizes (0-12 or 0-16) yet other orders would include a handful of garments in Plus sizes (most typically deemed sizes 16 – 3X). These garments either ended up merchandised in the back of the store by Clearance Items in a small section called Extra Fresh, or, they were sold online. Plus sizes were never promoted; shoppers found them on their own.

This limited inventory was approximately 7% of total company sales. From this figure, 10% came from online purchases and the balance was unevenly distributed across the retail stores owing in part to the inconsistent supply and assortment.

Based on the expense of maintaining this random Plus inventory in the stores, and the organic sales of Plus items which required no marketing spend, the CEO decided to migrate their Plus items to be exclusively online. He believed that these garments were occupying valuable retail footprint and square footage that should be reallocated to more fashion-forward, younger styles in straight sizes that could attract a new consumer and mitigate the investors concern. To him, Extra Fresh appeared as a peculiarity of the supply chain.

Organizational Fallout Calls for a Pause

“She’s not our core customer” and “her clothes cost more to make” became the rationale when the move to pull Plus from stores was announced by the CEO at the Annual National Meeting with store managers. This announcement was met with unexpected and unanimous outrage from store staff (who even a threatened mutiny!). The founder pressed pause. This was a move to drive business, why were the managers so upset? What connection existed between the Plus shopper and the brand since marketing was never directed at her? Why were Plus women shopping there and how had they found the brand?

After the national meeting, the CMO tasked his staff to conduct an audit of the Plus offering from competitive casualwear brands. He also began to do more specific social listening with Plus women across various content/social platforms.

A key takeaway from this initiative was that Plus shoppers generally accept, but resent, being “stuck in the back of the store”; which happens both literally in bricks and mortar stores and figuratively in online retail user experiences. Fresh Produce was no exception here. Competitive specialty retailers like Chico’s, Talbot’s, and Lands’ End all seemed to sidestep their Plus offering in some way. For example, no dedicated Plus section in stores; no Plus navigation online; no Plus models or merchandising – all despite social media posts from larger Plus sized shoppers. The big box fast-fashion retailers like H&M and Forever 21 were moderately more accommodating to Plus but aim for a much younger demographic.

Another key takeaway was that the Plus shopper tends to shop anywhere as well as up and down the age demographic of a store regardless of her age – from Forever 21 to Lane Bryant. This learning was echoed in conversations with store managers who plead with leadership not to eliminate Extra Fresh Plus sizes in the stores because “she has nowhere to shop”.

Armed with a bit more of a backdrop around the emotion from store managers, the CMO hired Bad Babysitter who specializes in video-based ethnographic research. He was seeking data and counsel that would help navigate the conflict between the CEO’s business direction and the store managers’ willful protest.

MEETING THE PEOPLE BEHIND THE BRAND

Upon arriving for a daylong introduction to the staff at headquarters, the ethnographers were able to make many immediate observations:

- The executive team consisted of men and women, none overweight

- Located in Boulder (a city known for fitness), the office provided all manner of healthy lifestyle benefits for employees (eg organic snacks, bike racks, etc)

- There was only one Plus size employee (who reported to the CMO)

- There was a large banner painted on the wall in the main office work space declaring “Every woman deserves a pretty dress”

Throughout the day, the ethnographers held informal meetings where various mid-level managers shared their responsibilities as well as their own personal take on what had happened at the Annual National Meeting. This included managers in merchandising, sourcing, designers/buyers, wholesale sales, HR/training, customer service, operations, and field services.

One-on-one meetings were also conducted with the executive team. Below are verbatim comments about the Plus shopper from those discovery meetings:

“She likes our clothes because they are loose; she wants to hide her belly”

“Our stores are in coastal towns, but large women don’t like the beach”

“She would rather try clothes on at home away from thin women”

“She finds her size in the store, but goes home to purchase online”

“Larger women aren’t as into fashion as regular sized women”

“I think larger women like to dress in color and that’s how she found our clothes”

The last meeting of the day was a one-on-one conversation with the founder. She reiterated how surprised and bothered she was by what happened at the national meeting. She underscored her desire to empower her new team and to address the business challenges that had been laid out to her. But most emphatically, she conveyed that she is a person who believes in mindfulness and the power of intention. This directive formed the backbone of the brief: help Fresh Produce declare and execute an intention with the Plus Size consumer so nothing ever feels haphazard or like an afterthought for the brand. If Fresh Produce was going to sell Plus garments, then it should do it with intention.

FRAMING THE RESEARCH

In a subsequent work session with the CMO, the ethnographers pointed out the conviction that headquarters staff had around the Plus shopper in the absence of any proprietary primary data to support it. This conjecture had, with no malice, become an organizationally accepted perspective. This became the starting outline for a loose research brief. Fresh Produce still did not know exactly what it was looking for, but the CMO believed that this shopper “needed to be brought into the room”. He was fairly open-ended on what that looked like; he just knew that organizational alignment was imperative for the brand to move forward.

There were limited resources (time and money) to study both the online and offline ecosystem in-depth as discreet experiences. Rather, the CMO decided to focus a qualitative research effort on understanding the Plus shopper’s more general experience finding fashion as a Plus woman. The research objectives centered around three areas of exploration: understanding the signals and markers for how she appraises positive (or fruitless) shopping experiences; how does she categorize various clothing retailers who “embrace Plus”; how do Plus women relate to the brand promise of Fresh Produce.

Advance Preparation

As a way to situate them in the Plus fashion marketplace, the ethnographers undertook a bit of ad hoc research to inform the research design and focus. They conducted secondary research to locate and describe the cultural point in time that America was in with regard to obesity and size relative to fashion, popular culture, and body image.

First, the ethnographers investigated the actual Plus fashion offering in the marketplace. This involved store/website visits to competing brands (Chicos, Talbots, Old Navy, H&M, Mod Cloth, Forever 21, Zulily) as well as dedicated Plus brands (Lane Bryant, Torrid). Informal social listening was done on the cultural conversation around size on women’s fashion blogs, fashion magazines, and social media. The ethnographers also became familiarized with the emerging feminist Body Positive movement (#BoPo).

The store visits set the stage for understanding the assortment, merchandising, presentation, and availability of on-trend Plus clothing. The social listening painted a picture of cultural debate around size – everything from obesity, runway models, discrimination, vanity sizing, advertising, and projected ideals of sexuality.

All manner of fat shaming and stereotypes of Plus women as sloppy under-achievers were encountered in comments sections of articles. Cultural bias created by the fashion industry and advertising was a prominent theme. Communities of outspoken body activists were publishing stories of baby step body positive advancements within fashion – a size 10 or above model here and there, Melissa McCarthy (here and here) on the red carpet, Tadashi Shoji couture for Plus (here).

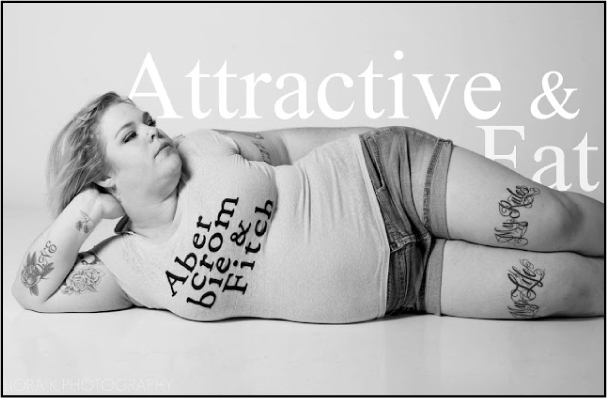

A cultural tension appears when the perpetuation of female body ideals square with the hard data of obesity in America. Over one-third (35.7%) of Americans are considered obese (a BMI of 30+). What is considered healthy, attractive, and normal has become distorted depending on what you read and who the messenger is.

Jes Baker. Body Positive activist who participated in our study.

Research Design and Project Methodology

Working in collaboration with the CMO, the unique challenges and opportunities for video to “bring her into the room” in an intimate and personal way were discussed. Using video as a primary data collection tool has many clear advantages: it captures environments, facial expressions, body language, and subtle non-verbal communication that would otherwise be difficult to describe through words. Something as important as a long sigh, or a hesitation, is an important detail that is lost without quality audio. Equally, video allows the participant to “show” her life. In order for it to be as effective as possible for such a sensitive subject, Bad Babysitter took extra steps to enroll participants as co-creators in the telling of their own story. This cooperation realizes its full potential if the ethnographic filmmaker is able to make the technology “disappear” and put the subject completely at ease.

However, the most often overlooked craft of video-ethnography is the editing. Video becomes the language that conveys the meaning and the humanity. Because this study was a fairly open-ended exploration, it was especially important for the ethnographers to discuss how they would respectfully contextualize each participant as an individual, while providing a broader Plus Woman narrative. Video editing adds an additional layer of analytic integrity and authorial control. Cutting and pacing require a conscious balance between faithful reportage and storytelling production values.

Data was collected in four ways:

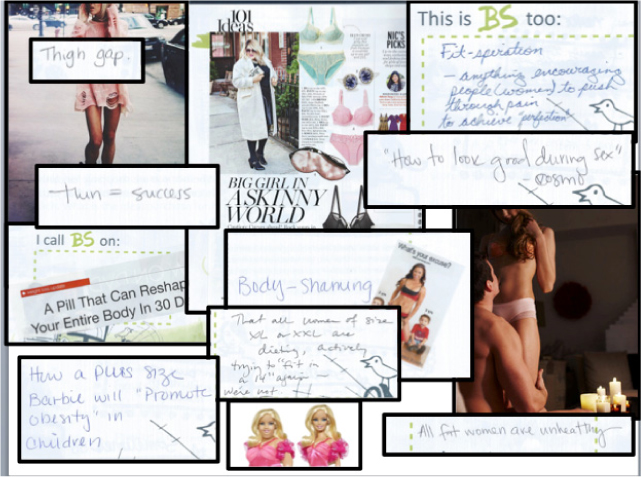

- A pre-work workbook that each participant completed individually. The workbook included a promotional code to visit the Fresh Produce website, shop, and buy. Participants recorded feelings about shopping for clothes and their Fresh Produce online experience. They also created collages to represent the media’s portrayal of women and beauty ideals.

- In-home one-on-one/dyad interviews that lasted between 2-3 hours and took place over a light meal (photographed artifacts were also collected in home). A friendship group was also conducted with 5 Body Positive women. During the sessions, an exercise was conducted using photos of so-called Plus models from size 12 – 28. Participants were asked to project their feelings onto the models and to provide improvised commentary about the photographs.

- Shopalongs at the Fresh Produce store.

- In-store observation. This would be a critical piece to gain insight into the store managers relationship with customers and the more sensory part of the Fresh Produce brand experience.

In the end, over 50 hours of video were analyzed, 15 hours of store observation was conducted, and 17 workbooks were coded.

From the workbooks, this is a collage of media messages that Plus size women “call BS” on.

Recruiting the Participants

The CMO selected three markets based on store sales: Tuscon, AZ; St Augustine FL; Naples, FL. In-store observation also took place in every location.

The ethnographers elect to do all recruiting themselves. Lists of prospective participants were culled from permission-based emails to Fresh Produce customers, in-store invitations to the study, and social media channels.

Some unanticipated considerations emerged during the recruiting process. Despite measures taken for sensitivity, the ethnographers encountered a healthy skepticism around the intentions of the project. At the onset, they were collecting data on what language comes off as direct and honest and what sounds like careful obfuscation of the fact they wanted to talk to women because they were overweight. This led to a heightened concern around sensitivity.

The final sample included 17 women aged 27–67 and size 14–3X. The friendship group represented the youngest women and they self-identified as “body positive” – they are proud of their size and take an active stance against fat shaming. Due to the mistrust encountered during the recruiting, the approach was adapted to encourage the women to talk openly about their size. There was a mother/daughter session. There was a session with two best friends, a session with a Plus fashion blogger, and a session with a Plus dress designer who creates bespoke garments for young women as a type of social entrepreneurship.

It is necessary to earn participant trust up front before an ethnographer shows up with a camera. It bears mentioning that neither the interviewer (a female) nor videographer (a male) are Plus sized people. Based on the hurdles in the recruiting process, the ethnographers debated whether their weight and having a man on the team would compromise how open the women would be willing to be. After so much effort to create “safe space” would our Plus woman feel betrayed to discover that the ethnographers were not Plus sized? Or that one was a man? It is not standard practice to reveal an ethnographer’s demographics to make someone comfortable. However, there is an additional level of intimacy that attaching a microphone and pointing a camera brokers. Ultimately it was decided that to make an issue of their average size was precisely that – making an issue.

SEEN, HEARD, AND SHARED ON VIDEO

Findings were delivered in a multi-media presentation in Keynote. Embedded in the presentation was approximately 90 minutes of video vignettes edited into a storytelling narrative which integrated photographs and workbook artifacts from the fieldwork.

This is a summary of what was seen and heard in the research documentary:

The women we spoke with agree that fashion publications and advertising perpetuate a distorted body ideal. A size 8 model is considered “Plus”; a size 12 model is lauded on the runway as a cutting edge event. While this absence of a true representation of size doesn’t stop a Plus size woman from imagining herself in the latest dress, it does play into larger pop culture tropes about money, sex and power. A common theme in the childhood memories of these women is that Plus size girls learn from an early age that it’s the skinny girl “who gets the job, gets the boy…and becomes successful”.

The Plus shopper is keenly aware of the assumptions made about her lifestyle and the media inferences that “fat girls” are unhappy and ashamed of their body.

Beyond these media images, our subjects identified the assumptions about Plus women thrust upon us from the weight loss industry. The weight loss industry is a key culprit in painting Plus as a market that is in flux – women who will start spending on fashionable clothing once they lose weight. It is a multi-billion dollar industry based on selling a sort of deferred happiness and postponed self-acceptance predicated on reaching a goal size.

The presumptive logic is: if you are large, you surely want to be small. This culturally conditioned belief that a Plus woman is uncomfortable with her size and wants to change creates a paradigm that suggests she is in flux and as such her fashion sensibility is too. Consequently, a very limited supply of fashionable Plus clothing is even manufactured. Plus women must often settle for baggy “mumus”. The misperception that she wants to hide her body “under a tent” feeds the cycle of stereotyping.

There is a literal dearth of selection for her. This realization came to light through the ethnographers pre-work and through the in-home interviews. Participants showed us garments they purchased even though they didn’t like them because they were afraid they might not find anything in future trips (in one case, the garments still had the tags on). But perhaps most powerful was the data collected during the shopalongs and in-store observations. Repeatedly, the Plus women would briefly peruse styles at the front of the store and then make a beeline to the back of the store. She scans the straight-sizes to see what’s on trend but is relegated to the limited inventory in the Plus section. Often, a Plus sized woman is forced to buy what is available, versus what she actually finds cute. The Plus section typically lacks in merchandising, is not maintained, and often cramped compared to the rest of the store. This holds true online as well – navigation to Plus sections are separate and many times the presentation and photos are “stripped down” versions of the main page where straight sizes are shown.

Sizing interpretations are all over the map. Plus models are either thin women in too large garments or big women in “apologetic” poses that don’t properly show how the garment moves or drapes. This makes it incredibly difficult to know if what you see in the catalog is what you are actually getting, let alone how it might actually fit on a larger silhouette.

Further, her clothes are often made of cheaper fabric and shapeless patterns. Key details like pockets or zippers are often missing as a way for a manufacturer to manage cost of goods. In the shopalongs, the participants repeatedly pulled examples of a straight-sized garment off the rack to compare it to the Plus version of the same garment. They were quick to point out differences in attention to tailoring, sexiness, detailing, and structure. In one instance, a participant noted that there is no cashmere for big girls. Another participant showed a particular pair of Capri pants offered in straight and Plus size. The straight size had a zipper, was thick denim, and rolled up legs with buttons; the Plus size had a drawstring, was flimsy cotton, and had no detail on the legs. Same garment name, same price, different quality.

This shortage of supply and style inspires a certain doggedness in some Plus women; they become skilled searchers who will look anywhere and everywhere for clothing. They find garments and modify them in some way. For others though, the process quickly becomes de-moralizing and they find themselves settling for ill-fitting clothes, in colors they don’t like, and in outdated styles. This creates a circular false demand in the marketplace. Manufacturers cut corners and play things safe based on what sells, but garments sell because there is limited choice and defeat.

For the Plus sized women in this study, they indicated they would continue to tolerate the insult of having to walk past “the cute trendy clothes” in the front of the store if only some of the same garments and fabrics were offered in her size. She simply wants what everyone else has – a sense of belonging and inclusion that comes from dressing in style and looking put together.

A final, important summary point to the shopalongs and in-store observation is that the ethnographers saw firsthand a particular sisterhood between Fresh Produce store staff and Plus shoppers. Repeatedly, the ethnographers witnessed sales staff enthusiastically offer things that “might work” and try in vain to help the Plus shopper leave the store with something she actually wanted. Plus women were greeted by name in some cases; it was not uncommon for straight-sized regulars to bring their Plus friends to shop.

Regardless, the brand behavior at the store level was genuine testimony to the brand ethos that “every woman deserves a pretty dress”. It became evident to the ethnographers, that herein lay the rub at the national meeting between home office and the field: headquarters had become disconnected from the shopper and the deeper, more demonstrative emotional equities the brand had to offer. Store staff intuitively felt that removing Plus from the store would erode the optimistic and positive spirit of the brand translated through actual customer interactions.

The quintessential “mumu” for Plus size women is boxy, shapeless, and often an outdated floral print.

Echoes from the Secondary Research

During the initial in-person introductions in the field (after weeks corresponding by phone and email), the ethnographers reiterated that the they were there to listen, learn, and capture whatever the participant wanted to share about being a Plus woman. From the very first home interview to the last shopping trip together, what Bad Babysitter witnessed was incredible candor and a demonstrable personal imperative to de-stigmatize women of size. This simple observation ran parallel to what the secondary research intimated: there is a cultural current underway for women who want to “take back” body image from mainstream media.

Analyzing the Data

The analysis yielded a half dozen themes that provided an organizational scheme for the client to unpack the findings in a linear, step-by-step manner. From these themes, five key insights were derived.

The themes provided specific topic areas to workshop:

- Fit and fabric are key equities that need to be sharpened

- The model is a critical piece

- There is a cuteness chasm

- Plus just wants what skinny girls have

- Inclusion and diversity cue relevance

- The BoPo tipping point is a business tipping point

The insights provided a more textured and conceptual basis for both strategic and tactical implementation:

Insight 1: Plus women are all on a spectrum of self-acceptance that influences their lens for evaluating models and clothing – they are looking for the confidence in models that they struggle to have everyday.

Insight 2: When clothes feel sloppy or baggy, they play into the stereotype that fat people are lazy, underachievers who don’t care about themselves.

Insight 3: Big girls feel marginalized by society, making them feel separate and invisible. They believe that boxy or “tenty” clothes are fashion and culture’s way of keeping her down.

Insight 4: Plus girls have a habit of deferring happiness because they’ve been brought up to believe that it truly happens once you lose the weight. This makes them defer spending and their enjoyment of clothes (but what they really want is to look good now).

Insight 5: Her antenna is always up for anything that signals inclusion. Big girls just want the same sense of belonging that can come from dressing in style and looking put together.

REACTIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS, AND MOBILIZING

At the close of the presentation, which included some very emotional moments triggered by participant testimonial on video, the room was silent. Not only had the leadership team seen and heard from an under-served consumer, they sensed that they were inadvertently marginalizing Plus women in their own stores through disparate products and shopping experiences.

The CEO was the first to speak and he simply said, “I had no idea”. The room shared his sentiment. Then, the founder stood up and acknowledged that the brand’s values had not been lived up to. She called upon the CMO to lead a cross-functional team to figure out a way to determine what the impact on business would be if the Plus woman was approached with intention.

At this point Bad Babysitter shifted into a consulting role to help make the insights actionable. Together, it was agreed upon that a Pilot Test would fulfill the founder’s request.

This involved re-imagining the garments themselves. Eight garments that were popular in straight-sizes but not available for Plus were selected for the Pilot Test; these Test garments would be made available online and in every company-owned retail store.

Then, themes and insights from the research were used as a lens to critically evaluate, end to end, the Plus shopper’s experience along the path to purchase. Each touch point was an opportunity to create new value for the Plus shopper.

- How can Fresh Produce sharpen the equities of fit and fabric without losing the relaxed vibe? How do they avoid playing into stereotypes with fit? How do they give her what skinny girls have?

- How do they get the model right? How can they signal inclusion? How can they celebrate the Plus woman without pandering to her size?

- How can they help her feel good now? What tools does she need to feel like she’s getting the size right the first time?

The client acted upon these specific recommendations from Bad Babysitter. A task force team was formed and the Pilot Test garments, marketing, and training was ready to roll in a short four months:

Design: Re-cut the patterns for the Plus body (vs the standard of scaling up by simply expanding the pattern).

Sourcing: Instruct the supply chain to source the same fabric and detailing used for straight-sized garments (vs the practice of sourcing cheaper fabric and omitting detail to manage cost of goods).

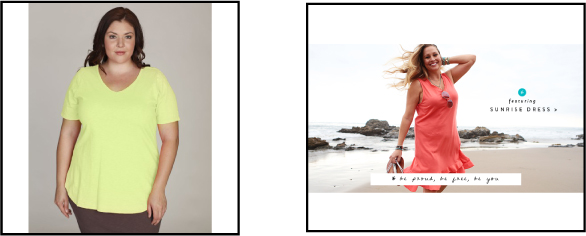

Photography: Hire a true Plus model and photograph her wearing her true size. The consultants developed a set of guidelines that were provided to the photographer to coach him to avoid “apologetic poses” and direct the model to “own her size”. Accessorize Plus in the same way straight gets accessorized. Integrate the Plus model in active lifestyle scenes that include traditional models.

In-store Merchandising: Include a Plus mannequin with straight-sized mannequins in window display. Move Test garments up closer to front of store.

Marketing: Re-write copy to be more specific about fit and how the garment is intended to drape. Call out the Test garments with an icon that leads them to dedicated online content describing fit.

Customer Service and Store Personnel Training: Provide staff with information on how to guide the shopper to figure-flattering fits and accessorizing.

Fresh Produce designers re-cut the pattern of a popular dress for the Pilot Test.

SOCIALIZING THE LEARNING, IMPACTING THE BUSINESS

After the initial presentation to the leadership team, the presentation was subsequently given to the entire headquarters staff as well as marketing agency partners. Video provided a shared vocabulary and visualization for employees to discuss. When customers are brought to life in video-ethnography, clients are able to internalize and communicate not only how the research makes them think, but also how the research makes them feel. It creates an easy repeatable way to workshop the learning.

In just 60 days from the launch, sales of the Test garments were up 500%. Overall Plus sales rose 9%. A CEO that was going to scale back and limit the Plus offering ended up investing in the Plus shopper, including Plus models in every look book, and integrating Plus in the store experience.

Almost immediately after the launch of the Pilot Test garments, social media channels saw quantitative lift and qualitative feedback from Plus and non-Plus women praising the initiative. Customer-service reps tracked and reported key fit questions and garment returns and were able to rapidly improve service levels. These reps also shared feedback from elated customers; comments were proudly printed and pinned to the walls in the company lunchroom. And critically, the store managers felt listened to and empowered to make their store a place where all women were celebrated equally.

Prevailing stereotypes, reinforced by popular culture, can blind a brand to real market opportunity. Fresh Produce found a younger segment in Plus and another local shopper to help offset the snowbird tourist business. Sales were up.

Not only did Fresh Produce discover an under-served woman with money to spend, the brand earned a halo of progressive relevance through size diversity. In 2014 they found themselves at the vanguard of some tipping points for the Body Positive movement in the broader popular culture. They were able to now join the larger conversation among women.

Perhaps most important, was the organizational alignment throughout the company culture. The CMO forwarded multiple emails exalting the energy and excitement that the launch had created internally. And for his part, he shared his pride that everyday when he sees the mantra on the wall that “Every woman deserves a pretty dress”, he knows the brand is living up to.

How Plus was merchandised before the research (left). Applying the learning to create a new presentation of the Plus woman (right).

Our recommendations were aimed at creating new value at every touch point from pattern design to merchandising to purchase.

Meg Kinney and Hal Phillips are the founders of Bad Babysitter, a new breed video-based research and strategy practice that put a human face on the numbers. We combine ethnography, storytelling, and business acumen to deliver consumer insights through documentary-style videos that give leaders critical and unprecedented understanding of the people they serve.

REFERENCES CITED

Roach, Mary Ellen and Bubolz Eicher, Joanne

2007 “The Language of Personal Adornment” in Fashion Theory – A Reader, ed. Malcomb Barnard (New York, NY)

Holliday, Ruth

2007 “The Comfort of Identity” in Fashion Theory – A Reader, ed. Malcomb Barnard (New York, NY)

Entwistle, Joanne

2007 “Power Dressing and the Construction of the Career Woman” in Fashion Theory – A Reader, ed. Malcomb Barnard (New York, NY)

Influencer engagement. Accessed December 2013 – March 2014:

The Militant Baker. http://www.themilitantbaker.com/

Candy Strike. http://www.candy-strike.com/

Kirsten Marie. http://www.kirstinmarie.com/

Plus Model Magazine. http://www.plus-model-mag.com/

The Curvy Fashionista. www.curvyfashionista.com

BeauCoo. www.beaucoo.com

Venus Diva. http://dailyvenusdiva.com/

Curvy Girl Chic. http://www.curvygirlchic.com/p/about.html

Government data:

http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

Social listening: Blogs, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest

Proprietary data from the client: competitive analysis, competitive e-commerce analysis, sales and transaction data