Ethnographers, in a sense, play the role of story creators, storytellers, and, often, preservers of such stories. The narratives produced and the fieldwork from which they emerge make visible trajectories of practice—for both subjects and researchers— which can be traced both retrospectively and projectively. For “in-house” ethnographers engaged in the sustained work of making sense of and contributing to organizations, a unique challenge emerges: discovering and managing the retrospective and prospective meaning of their storytelling and its visibility. Here we reflect on the challenges and opportunities of sustaining ethnographic inquiry in a large global software company. Reflecting on close to ten years of participant observation, we outline some of our practices related to positioning, re-framing, and expanding the visibility of our work and our organizational roles; a dynamic that continues to shape our practice and its relevance within this corporate environment.

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, applied ethnographic practice has made significant contributions to product and service design, program evaluation, overall strategy (e.g. Luff, 2000), and other organizational practices. In addition to extending the usefulness of the ethnographic method, these practices have also brought to light new methodological and ethical dilemmas (Fetterman, 1998). In this paper, we concentrate on the unique challenges that emerge from the sustained participation of ethnographers in organizational life as “in-house” social scientists and, in particular, on the practices related to managing the visibility of field data, interpretation practices, artifacts, and the researchers’ roles themselves. We have come to believe that new methods and approaches might be necessary in this area based on the ways that our ongoing and complex relationships with sponsors, stakeholders, and subjects constantly challenge us to actively monitor the retrospective and prospective meaning of our work and its visibility. In considering the visibility of field data and of our roles retrospectively we engage in “sense discovery” or “sense making” by segmenting, associating and synthesizing elements of the research participant’s experience as well as our own. Prospective visibility challenges us to engage in “sense projecting” or envisioning possible futures within the boundaries of a context of study as well as for ourselves. Before exploring some of these challenges and the ways we have come to understand and approach them, we outline the ways in which both of authors have come to our current organization, as well as what informs our views on this topic. In the spirit of reflective ethnography we report on our experiences, in an attempt to engage in a dialog with other practitioners regarding the pervasiveness of these situations and the need for collective thinking on ways to approach them.

Although almost all of the activities reported in the remaining sections correspond to the history of Natalie’s professional practice at SAP, in many cases we will adopt the plural form for narrative convenience as well as aid in the reading of our accounts as practices that could be of value to others. Natalie came to the organization about ten years ago into a technical position while working on her Anthropology doctorate. In the intervening years, Natalie has moved into a management role and formed a small User Experience team. That team has grown to include interaction designers, information architects, and most recently Human Factors expertise. Johann recently joined the User Experience team after completing his dissertation work in Human-computer Interaction in a different context.

SAP is a large software company with offices throughout the world.1 While the company does provide software-related services like consulting and training, the majority of the its revenue is delivered through license sales of its numerous software solutions. The software industry is a dynamic one, and its volatile nature in turn affects how companies are required to operate. In the past decade, SAP has become a publicly-traded company and undergone severl strategic alignments including a significant number of mergers and acquisitions by SAP as well as by its competitors. With company sizes and revenues soaring, analysts have focused increasingly on the profitability of SAP and its peers. In turn, there has been a growing interest internally on managing margins, and operations functions have rapidly appeared across the company, emerging as a new form of concentrated expertise to address this new corporate priority.

In parallel to other duties at SAP, Natalie conducted research that focused on changes in high-tech industry following Y2K, the dot-com crash, and 9/11. A central goal of that work was to understand how a growing focus on the market and on customers manifested in changes internal to the corporation and the management of employees. Consistent with that industry trend, in recent years SAP has made a conscious shift from being a technology-driven company, to one that is much more attuned to the market and its customers. This shift has resulted in an internal discourse and set of practices targeted at raising employee awareness of and responsiveness to the market and customers. (Hanson 2004) This interest in consumer behavior (end-users in the software industry) had resulted in a resurgence of interest in ethnographic methods in business, and there were a growing number of articles appearing in the U.S. media about anthropologists and ethnographic methods. While not the subject of this paper, that discourse served as a backdrop for the positioning of user research through ethnographic methods as an operational practice inside of SAP.

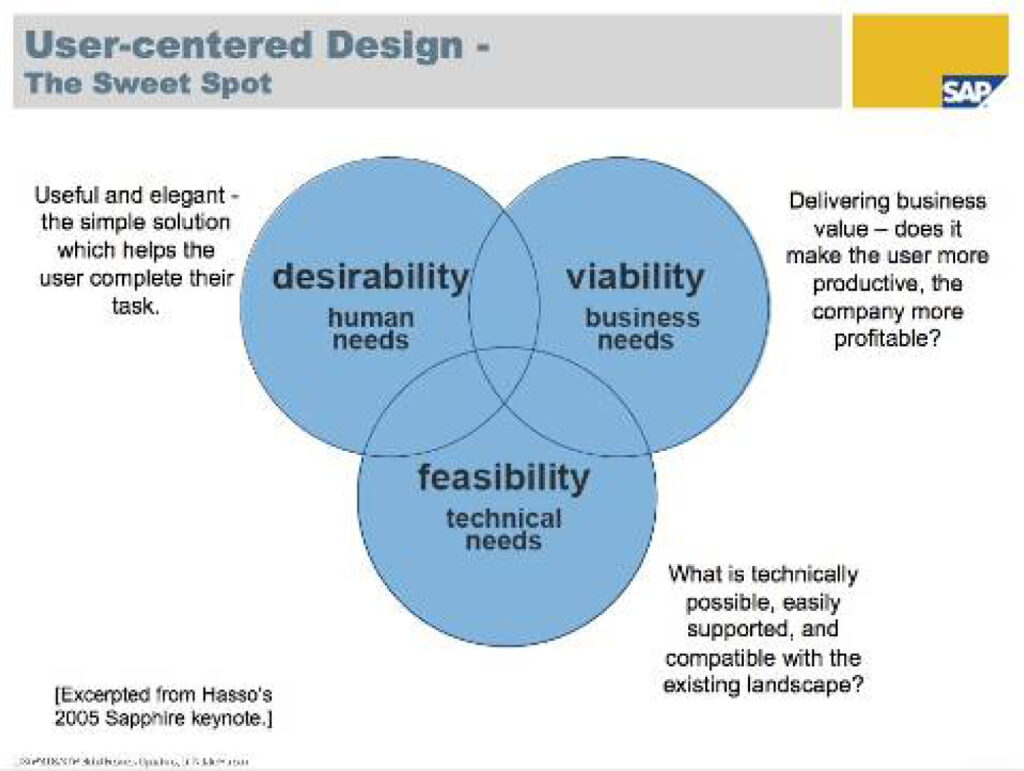

Lucy Suchman (2000) argues that “the interest in corporate anthropology involves the anthropologist herself in an identity marked as exotic Other within the context of familiar commercial and technological worlds”. It is true that at the outset, an anthropologist within an organization like ours was a source of curiosity more than anything else. Co-workers described themselves affectionately as Natalie’s “specimens”, without really understanding why an anthropologist would be interested in the corporate context. Using her colleagues’ curiosity as a launching point, Natalie began to talk with her colleagues more and more about her research, and the growing use of ethnographic methods in business. Natalie used familiar consulting tools like the Venn diagram to build the bridge between the consulting approaches familiar to SAP, the ‘exotic’ new perspectives that anthropology could bring.

The Venn diagram above was used by SAP founder Hasso Plattner at SAP’s annual conference, Sapphire. Natalie and her team added some additional descriptive text, and we continue to use it today to raise awareness about the user perspective in consulting engagements in cases where technology and business requirements are known, but user requirements are not well understood. This visualization also enables the team to explain the importance of user-centered design, user experience, and social science methods to stakeholders inside of SAP.

Although far from a comprehensive description of our work context and experiences, the previous paragraphs have outlined some of the factors that shape our organizational practice today, The remaining sections illustrate the perils and opportunities derived from our sustained participation in organizational context, specifically as they related to how we manage the visibility of ourselves and our research, as well as the meaning of our practices..

Vignette I. Make the Unseen Visible, but Losing it from Sight: The Woeful Pie Chart

After having expressed the wish to bring her anthropological training to bear on her work at SAP, Natalie was given the opportunity to conduct a research study as a ‘proof-of-concept’ for what might be possible. That study has come to mark the beginning of the User Experience function in SAP’s Business Operations group. At the time, the operations function in the U.S. was focused almost exclusively on the sales line of business. The team’s charter was to increase the productivity of sales people, as measured by (among other things) license sales revenue per sales representative. It is therefore not surprising that this first research project involved shadowing revenue-generating employees. The research was justified to an executive team on the basis of the opportunities it brought to understanding sales activities, specifically looking for opportunities to increase their productivity.

At that moment, Natalie was the sole researcher who handled almost every aspect of the study– recruiting, scheduling, capturing field notes, data analysis, and the reporting of results. The final deliverables included a presentation that was given to the Senior Vice President (SVP) of Business Operations (the project sponsor) with a list of possible action items, including business scenarios illustrated with quotes from study participants, and a series of recommendations. This type of work is perhaps the standard of ethnographic practice at the service of business strategy in which the “unseen” of work practices is reconstructed and made accessible to decision makers who might be unaware or distant from it. Messaging such findings involves the creation of reports, diagrams and other artifacts that attempt to serve as boundary objects (Star & Griesemer, 1989) between recipients and researchers.

In this case, the presentation materials produced included a slide that attempted to visualize the frequency with which certain key activities occurred. It was a pie chart based on the coded data, intended to provide visual impact and designed as an anchor point for discussion with executives who might not tolerate the narrative detail in the findings. When the study results were presented to the Senior Vice President of Business Operations, this pie chart was used in addition to informal, verbal findings; the complete presentation materials were delivered later to an entire management team.

At the time, this pie chart in particular appeared to be extremely effective in stimulating dialog with the sponsor and others about the complex stories and data behind it. In fact, it effectively enabled messaging of complex findings all the way to the executive level, a success rarely experienced for this kind of work. Without it, the research and its outcomes may have not had the same lasting success. At this point, it appears to be the only artifact from the research that is still circulating. To the best of our knowledge, none of the detailed business scenarios (or even the sales people screen shots) have been distributed further, despite those being, from our point of view, the most interesting and valuable aspects of that research. We have come to call it the “woeful” pie chart, the one which has been used and re-used the most, and in many cases, unfortunately, misused and surely misinterpreted. This might be an inescapable fact of ethnographic practice. Or perhaps the artifact itself, with its simplified and attractive appearance, affords the twisting and positioning to suit the needs of the speaker.

As professional practitioners and as members of our particular organization, we are still learning and re-learning that it is the contextual interpretation and ongoing analysis that makes field data useful—the nuances are not made visible except in situated conversations. Partly in response to this, we have made some changes in how we handle our reports today. For example, we insist on providing readouts before we distribute the soft copy of a report, and we provide private readouts to help interpret or expand on key topics. We hope that this approach will help our audience understand the richness and complexity of the findings, so that they will come back to us again and again, rather than assuming all the data they need is in the final deliverables. What we have come to learn from this experience illustrates the subtle ways in which we adapt our professional practices to suit the contexts in which we operate.

There had been a few other studies conducted during a similar time frame, carried out mostly by outside vendors. The first had yielded very general findings, and had not provided any significant new insights that could be used to drive productivity improvements. The second study had been conducted by a usability testing firm, and its results had limited value to the operations management team because the outcomes were narrowly focused largely on ways to improve the intranet. At the time, the research Natalie conducted had succeeded in looking for ‘white space’ (opportunities to improve productivity that might not have been uncovered otherwise) and that the research approach and final deliverables permitted the management team to more deeply perceive the problem areas, the frequency with which they were occurring, and to begin to understand the real impact from a salesperson’s point of view. The research also made visible problem areas that were known but were previously not well understood. The detailed findings and recommendations permitted a level of visibility on a core process that had previously not existed, and specifically showed the impact of those process breakdowns on sales productivity.

Overall, this initial work was perceived as innovative and adding value, and it contributed to the increased understanding of the management team of how anthropology and ethnographic practices could be blended with work in business operations. This initial success began to make ethnographic research methods visible within the organization, and opened the door for future engagements. However, as a junior member of the operations team, Natalie had very little opportunity to drive uptake of the findings, and almost no visibility into what was done to address the issues uncovered. Lack of direct access to members of the executive team, lack of influence in general, and lack of resources severely limited what could be done to extend and act on the findings. At least in part, some of these challenges related from “losing sight” of research findings are derived from the position that ethnographers might occupy in the organizational landscape, and the visibility and access that such position might afford them. At the time of our study, we didn’t have enough visibility and access to the corporate strategy and direction, which in turn made it challenging for us to message the findings in ways that would be compelling to senior management. Several more years and projects had to pass before a team dedicated to similar work was constituted and our work better positioned in a way that provided us visibility and the means to manage uptake.

In addition to these challenges, we also face the problem of being disconnected from the results of our work. We know that our findings have been used to build a number of business cases, but for the most part we have learned about them after the fact. Not too long ago, we learned that the COO was speaking with enthusiasm about a pie chart that showed where sales representatives were spending their time. A member of the leadership had to explain to the COO that the person who had done that research worked in their group. On one hand, it is fantastic to see that the research has had such lasting value; because so little has changed since for the salespeople, so most of the findings remain quite valid. One of the interesting things here is that the company has changed, sponsors and stakeholders have changed, but much of the day to day work that was originally the subject of study has not changed all that much in the intervening years. What is bothersome is that the team is not being recognized or acknowledged. As individual practitioners gain recognition and teams dedicated to similar practices emerge, it is common that resources need to be justified on a regular basis; having our work mis-interpreted (or not getting recognized for our work) can present a significant long-term risk for resource justification. Therefore, in such situations one has to be even more careful to ensure that proper work recognition is assured.

However, at that time, the entire concept of User Experience was still being proven. As such, the team’s primary charter was in technical realms, for example bridging between the business and IT or standard development. These factors influenced the way we thought of the solution space and its presentation – i.e. many of the recommendations were of technical nature and presented in that way. Some of the findings were in fact used to design and implement a small internal software application to support important but previously unidentified concerns of sales personnel. However, without significant resources at our disposal, it was extremely challenging to demonstrate the ways in which technical recommendations could have larger business impact. Perhaps most importantly, having a sole researcher on the project made it extremely difficult to manage the presentation of outcomes in ways that would be simple and compelling enough to engage an executive audience and sustain the visibility of the work. In hindsight, it is fortunate that our work was able to have any impact at all, even if in some cases such impact was not completely aligned with our intentions as researchers.

Vignette II. Projecting retrospective inquiry as relevant to the present and to a set of envisioned futures

Despite the troubled visibility of some of the artifacts produced from the initial study, it cannot be denied that eventually that research and other changes played a significant role in making our expertise visible and opening opportunities for further ethnographic work. A few years later, the regional Chief Information Officer came to us to find out what further research, if any, had been done on sales personnel. His interest was around the ways that the existing Customer Relationship Management (CRM) software was used by sales personnel to keep track of activities with their customers and prospects, communicate projected revenue by quarter, etc. Although we had conducted numerous user research studies within the sales and marketing organization (a few of them using ethnographic methods) none of them directly answered his questions. However, exploring the relevance of prior insights in new situations has become a way of opening up new opportunities for organizational contributions and, naturally, we were not going to miss an opportunity to present our work to the CIO! As a result, research findings from multiple prior studies were used to prepare a summary of what had been learned about the CRM implementation. In a personal meeting with the CIO, a general overview presentation of all the research projects was provided and then, through the course of the discussions, specific topic areas and supporting materials were reviewed based on what appeared most relevant for the questions at hand. While the overview presentation provided the framework for discussion, however, the majority of the data and the rich stories were exchanged during that meeting were anecdotal, drawn from memory and reconstructed based on the questions the executive was asking.

As a result of this “retrospective” presentation and the dialog that ensued, we had a chance to learn about a new program intended to bring improvements to the internal implementation of CRM. As it turns out, many of the areas that had been identified in the original ethnographic research on salespeople continued to be a challenge several years later. Most importantly, through our retrospective review, we had succeeded in making the sales point-of-view visible for the CIO and his project team. Inclusion of the users’ perspective at the outset of the project would be critical to ensure uptake on the improvements that were planned for the system. Some of our prior research, for instance, had shown that the sales people actually spent very little time online in front of a computer; they were hyper-connected, but it was largely via a Blackberry or mobile phone, and not using a computer browser. Even when sitting at their desks (which were equipped with land lines), they more often than not opted to use their cell phones. Of the time they spent in front of their computer, most of it was spent looking at market news and trends through a personalized service like Yahoo! Finance, and only a very short amount of time each week was spent in the CRM application itself. One insight we were able to bring to the conversation at the time was that the sales representative perceived the tool as a vehicle for management reporting, and therefore only maintained the fields that they knew would end up on an executive report, or that impacted how and how much they were being paid for the software licenses they sold.

Using historical information, we were able to present the system user’s point of view in a way that was unique inside SAP. Prospectively, we were able to position not only our expertise but the ethnographic approach as strategic and useful. After years of practice talking about the findings, we were finally confident that we were both sought for and able to speak to that point of view in a way that was compelling at the executive level. It was more than two years after that initial study, but it was the first time that we had been approached by a member of the executive team to provide insights on users at the outset of the project. Even more importantly, the research was now being used to enable strategy, prioritization, and funding decisions, and not simply system usability.

Vignette III. About Design: Prospective but Partially Blinded

A recent team engagement represents a clear example of how our trajectory of work has opened up significant avenues for key contributions of our ethnographic work as well as positioned us closer to the challenging area of organizational design. Motivated by cross-company tensions about the value being derived from a particular operations service offering and rather than continuing to point fingers, two former project sponsors recommended our services to another executive. We were asked to explore and analyze the field’s point of view on the service in question through a series of in-depth interviews.

As we were working on the interview protocol, we gained familiarity with the various parties involved. Recognizing the seniority of the individuals involved (and the tensions), the involvement of senior members of our team became essential. Through interactions with the various stakeholders, we learned that there were at least three distinct research agendas or objectives at play, and that – in order to ensure maximum uptake of our findings – we should do our best to accommodate all of them in the methods, the protocol, the findings report, and in the verbal delivery of findings. This is not an uncommon situation in which organizational ethnographers find themselves but little in our collective knowledge seems to speak to ways of managing such a challenge.

The main project sponsor appeared strongly committed to the ethnographic approach, very interested in hearing the field’s point of view. He enlisted our support to understand the issues, and identify areas where his global organization needed to change. The secondary sponsor was a regional executive who was interested in the same issues, but who also explicitly stated his interest in proposing a new regional organizational model based, perhaps, on his expectations of the findings. Finally, a third sponsor (to whom the first directly reported), was interested in ensuring that his organization remained aligned to the field’s priorities, thereby ensuring it’s ongoing relevance to the corporation. Identifying such diverse perspectives in the course of research planning helped in selecting the right approach to the design of the interviews but, naturally, some compromises were necessary. Thanks to prior research efforts and personal work of some team members as part of a regional sales operations group, we already had a fair amount of visibility into the challenges existing with the service in question. Specifically, it was clear that most of the formal processes were not well perceived in the field because they were slow and ineffective, and that as a result, personal networks and informal processes prevailed as a way to get the tasks completed. Considering all of this, we were able to formulate a protocol that pursued organizational issues directly. Rather than asking ‘how are these [formal] processes working for you?’, we asked more open-ended questions such as ‘how are you getting this task done?’ The process of defining the protocol itself involved extensive collaboration with some of the sponsors to validate and explain our approach.

The findings were not completely surprising and they did identify numerous areas of improvement. As a neutral third party were able to provide feedback to the stakeholders involved, well-grounded in data from their internal customers. In our professional commitment to make the context of our studies as visible and accessible to our sponsors as possible, we transcribe and code all of our interviews and create reports that are heavily enriched with direct quotes, making it quite explicit that we are presenting on behalf of the end-users. We take special precautions to make sure that the identity of our research participants does not get compromised in order to comply both to our ethical commitments as well as with the labor laws of the countries and regions in which we operate. As with our prior experiences, instead of disseminating reports indiscriminately we were especially careful to manage the issues uncovered as a dialog with all of the direct and indirect sponsors. This helps us to ensure that the data is made visible only to those that have requested the research. Not only does this practice ameliorate the possibility of misuse or misinterpretation of our findings but it establishes a strong partnership of collaboration with our sponsors where the interpretive sense-making is perceived as a shared responsibility. When we are successful in collaborating in this way, it helps to ensure that we remain engaged as experts on the data and its interpretation. In that way, we can help guide the development of an actionable plan that truly reflects the findings.

This type of relationship is especially key when we leave the problem space and attempt to reason through a possible set of solutions.

In this particular case, we were especially cautious about making explicit recommendations in the research report as we typically do for research on, for instance, information system design and user interfaces. When research is done in the service of organizational design, we have found that we can never put enough information into a written report. Even with a rigorous discovery process, the political landscape or objectives shift in the course of the research. As a result, we are always somewhat blind to how the research may be used, and whom it will impact. In other words, we have learned that trying to manage the future meaning of our work represents a significant challenge that often results in unintended and unplanned uses for the artifacts we produce. We try to keep our written reports tightly focused on the data. As much as possible, we then ask for a seat at the table to help with the interpretation of findings, and how they can be applied to solve the business challenges at hand. This type of conversation allows us not only to manage the way our inquiry serves the organizational needs at hand but also increases the visibility of our approach and the overall understanding of our potential roles in the future.

CONCLUSION

So after the first study was concluded, Natalie was invited to move into a growing, global team, and to build her own team from scratch. While her ability to manage technology and technical staff remained at the core of her value proposition to the company, she decided to use some of the now precious resources given to prove out what more could be done with something she had decided to name ‘User Experience’. An information designer was hired as the first team member who complemented the research activities being conducted. The rational for this move came from the belief that individuals trained in information architecture and design brought big picture thinking skills and experience interpreting business requirements that would be an asset to the development of the team. As illustrated in some of the vignettes presented earlier, we had seen significant rewards and challenges from being able to visualize findings and recommendations to stakeholders. So one of the biggest benefits predicted for working with a designer was that that person could help visualize research and recommendations in ways that would further accelerate understanding and appreciation of the role and relevance of User Experience.

In response to the growing focus on operational efficiency, the User Experience team has further formalizing how we work. We now function as a small consultancy; our services are managed and ‘sold’ internally as part of a broader services portfolio. That portfolio is managed and measured, which means that services have to demonstrate measurable impact in order to ensure budget and resource allocation in the annual planning cycle. All services have KPI reporting that is delivered up to our senior management. To support the positioning of our services, we have a service catalog in which our services and their value proposition and reference customers are presented. Each service offering has a standard deliverable(s), which is consistently branded. As mentioned earlier, we have a handful of sponsors who know us and our work very well. These executives serve as reference customers for us, and they also refer their peers to our organization. However, we continue to gain visibility and recognition for our work, we find that our ‘thump book’, a slide presentation of reference stories, combined with our growing reputation results in an appreciation of our capabilities and expertise without the need for a verbal reference. At this point, our main competition is outside consultancies, because they don’t require executive prioritization and support, and are sometimes able to respond more quickly. However, as the years progress, we are finding that our deep knowledge of the company and how it works (the institutional history, in some cases) is a competitive differentiator in getting us engaged in wide range of strategic projects.

Two years later, the User Experience team itself is larger than the entire original global support team created at the outset. Despite the personal or collective preference that we may have for the use of ethnographic methods, currently we employ them very selectively because this type of research is expensive and time consuming to execute. Unless ethnographic methods are formally requested, we typically find that in today’s economic conditions the organization has little tolerance for the time it takes to conduct the research, perform the analysis and prepare the final deliverables. Over time, we have learned that ethnographic methods are best deployed into ‘white space’ – or a broad area where there is an indication that problems exist but where the complexity of the situation is not fully understood. However, based on what we now know about the company’s direction, executive priorities, and so on, occasionally we take a calculated risk and deploy resources to conduct research before we’re asked, before a sponsor is named, or even before a project is formalized. That provides us with the lead time we need to get to know the situation, conduct some research, and be prepared for a formal consulting engagement. This can only be achieved in a context where longstanding relationships and trust have been established, sometimes even based on other types of work and skills that are brought to the table by recognizable individuals with a track record of organizational achievements.

As we continue to evolve as a team, we can say with confidence that our work in User Experience continues to exceed original expectations. We now have relationships with half a dozen executives who understand the organizational relevance of our work and the value it brings. Some of those executives have been customers more than once, and they tell other executives about the value they have derived from our services. There is, naturally, a great deal of personal rapport driving such relationships as some of those executives have both supported and witnessed individuals in the team evolve and grow along the years. In a corporate climate where organizational change and is the norm, these relationships are the mainstay of long-term success. We still support the organization’s internal systems, and that work ensures that we can continue to justify the company’s investment in User Experience employees and the corresponding budget necessary to operate the team. However, as the team evolves in its knowledge about the organization, its needs and goals, we are able to do the same work more efficiently; which in turn both frees us up for new work, and enables us to take on more complex projects.

Currently, our budget also enables us to work with vendors on larger projects, but in those cases our team members are tightly integrated – co-conducting the research and analysis, and in some cases also co-developing the final deliverables. We do this to ensure that we retain a deep understanding of the data that is so central to our team’s value. In cases where it is difficult or impossible for the team lead to actively participate in the research, special strategies are devised, as we have reflected through the previous sections, for the kinds of activities that allow us to manage the messaging of result, the reuse of accumulated knowledge, and the opening of new opportunities for our work to be relevant and of use. This involves very active and sometimes contentious participation in the construction of all final deliverables. Although the role of the team lead is most often to help the team better understand what is happening in the business (the most serious gap that faced the first author at the beginning of its professional trajectory in the organization) an active involvement in the construction of deliverables and other reporting activities ensures that the final report and readout is compelling to our sponsors and stakeholders.

In concluding, we have illustrated here some of the challenges that in-house ethnographers face when participating in long-term engagements in organizational life. In particular, we have reflected on some of the challenges and opportunities we have faced in evolving and sustaining our particular ethnographic practices. In the three vignettes presented practitioners in similar contexts might recognize some of their own challenges when faced with the ways that their own practices are received, used, and re-used over time. As a field, perhaps we need to engage in a collective conversation about these challenges and the practices that would allow us to overcome them.

Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2008, pp. 261–273. © American Anthropological Association, some rights reserved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As we have indicated throughout the text the insights reported, although emerging from the collaborative conversation of the authors, emerge from numerous interactions with colleagues, research sponsors and participants, supervisors and others within our organization. The views presented here are the personal views of the authors and do not represent the views of SAP or any of its affiliated organizations.

NOTES

1 While SAP does run its operations on SAP software, that is not the focus of this paper. In that regard, we believe that SAP represents a typical global organization, in which information technology and business strategy intertwine both as a service provided to potential clients and as an internal operational practice.

REFERENCES

Button, Graham. Editor

1993 Technology in Working Order: Studies of Work, Interaction, and Technology. London & New York: Routledge.

Hanson, Natalie.

2004 Consuming Work, Producing Self: Market Discourse in Dispersed Knowledge Work. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Temple University, Philadelphia.

Heath, Christian; Luff, Paul.

2000 Technology in Action. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press

Fetterman, David

1998 Ethnography. Thousand Oaks. Sage Publications

Forsythe, Diana E.

1999 “It’s Just a Matter of Common Sense: Ethnogrphay as Invisible Work”, Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Vol. 8, No. 1-2. pp. 127-145

Orbuch, T.

1997 “People’s accounts count: The sociology of accounts.” In J. Hagan and K. S. Cook (Eds.), Annual Review of Sociology, 24: 455-478. Pale Alto, CA: Annual Reviews.

Orr, J.

1996 Talking About Machines: An Ethnography of a Modern Job. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Rabinow, P.

1977 Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco. Berkeley, CA. University of California Press

Star, Susan., James. Griesmer.

1989 “Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology.” Social Studies of Science 19(3) 387-420.

Suchman, L.

1987 Plans and Situated Actions: The problem of human-machine communication. New York: Cambridge University Press.

2000 Anthropology as “Brand”: Reflections on corporate anthropology, published by the Department of Sociology, Lancaster University. Retrieved from: http://www.comp.lancaster.ac.uk/sociology/soc058ls.html