Case Study—In 2016 The Chicago Community Trust (“The Trust”), a local Chicago foundation, partnered with Roller Strategies (“Roller”), an international professional services firm, to deploy an innovative mixed-methods approach to community-driven social change on the South Side of Chicago. This partnership convened a diverse group of stakeholders representing a microcosm of the social system, and launched a project with the aim of developing resilient livelihoods for youth aged 18-26 in three specific South Side neighborhoods. Roller designed and facilitated a process through which the stakeholder group scoped, launched, piloted and prototyped community-driven initiatives. While innovative and successful by some metrics, the project had its challenges. The convening institutions and their staff were often perceived as “outsiders” and “experts” without intimate local knowledge of the social challenges they were attempting to address. This dynamic played out in complex power maneuvers across groups in the system. The cultural narratives and interests already at play in the system were employed by individuals and groups at all levels to shape the landscape of agency and power in the system, while attempting to retain the methodological and narrative legitimacy of the publicly-facing project. This case study will explore the narratives and power dynamics at play within the system, look into the causes of these dynamics, and explore the impact they had on the effectiveness of the project as a whole.

In order to collect “accurate data,” ethnographers violate the canons of positivist research; we become intimately involved with the people we study. (Philippe Bourgois, In Search of Respect, p.13)

INTRODUCTION

Convening, Scope, Organizations

Grove3547 was convened as a response to the question, How can we work together to support young people in Chicago to develop resilient livelihoods? This focus was developed during the course of the initial research and community outreach that marked the beginning of the project. As a place to start, The Trust was primarily concerned with the issues of systemic racism and gun violence in Chicago, but these issues are difficult to define, deeply contentious across political, racial and economic lines, and not specific enough to be actionable. As the demographic and ethnographic research at the beginning of the project was conducted, the project team began to focus in on a more specific and actionable framing of the challenge: developing resilient livelihoods for youth aged 18-26 from three specific neighborhoods in an area of the South Side called Bronzeville. This new focus reflected language that would appeal to people across the political and economic spectrum, would be possible to measure, and was seen as plausible (Bronzeville was chosen because it was both replete with social issues and home to a rich history and culture of entrepreneurship and social activism). This new focus also looked at the issues of race inequality and gun violence from a systemic perspective: If youth in this age group were able to develop rich, meaningful and sustainable livelihoods, the project team believed, race inequality and gun violence would decrease.

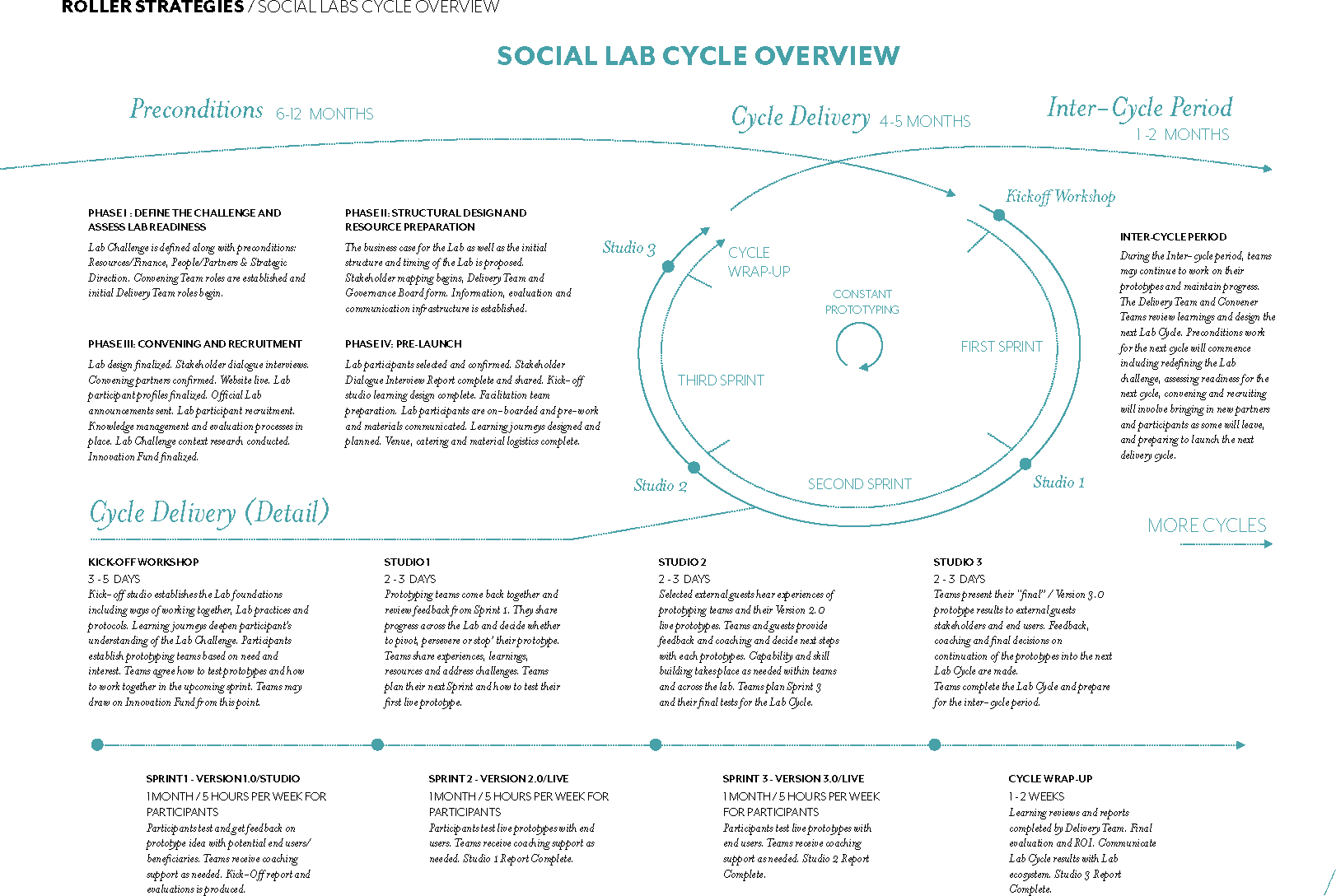

The project, Grove3547 or “The Grove”, was conceived as a strategic approach to addressing complex social challenges called a “Social Lab.” The Grove was organized as a series of workshops, a “Kickoff” workshop and three “Design Studios”. The Kickoff workshop would be an opportunity for the whole project to do a deep dive into the social system through interviews and learning journeys, begin to map the system and its dynamics, and based on the emerging system map, brainstorm potential leverage points and sites of interventions that could have the most impact. Teams formed around the most relevant leverage points, and began developing and prototyping potential interventions. The individual prototyping teams would meet weekly, coordinating activities in the field, and then the whole project team would meet once a month for a “Design Studio”, to present and review their work, share learnings with other teams, get feedback from the hosting team and stakeholders from other parts of the system, and to plan the next phase of their work.

Figure 1.

Social Labs, which draw from a variety of methods, processes and tools, are loosely characterized by Zaid Hassan as being social, experimental, and systemic in nature (Hassan, 13).

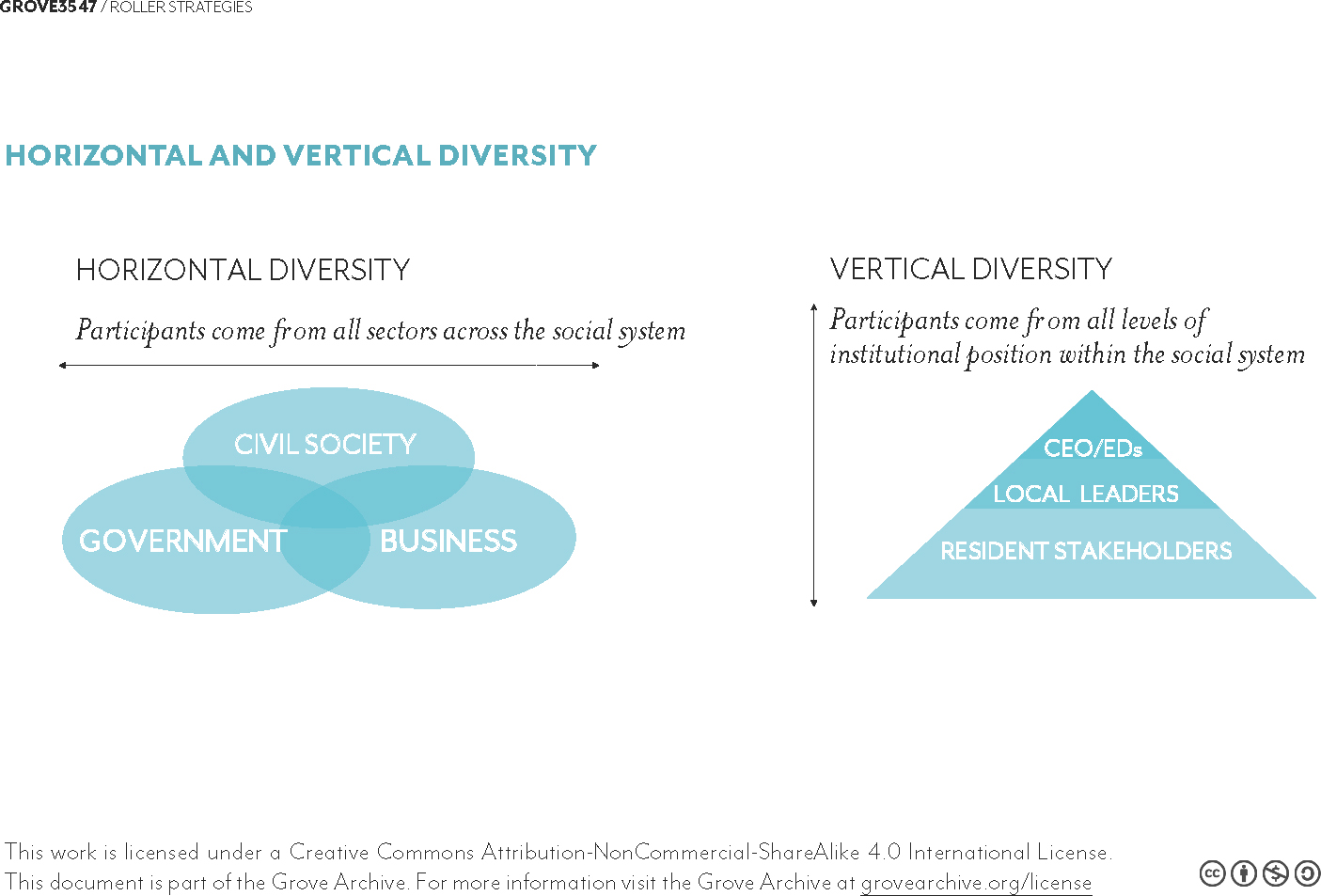

The social aspect of a Social Lab refers to the diversity of the group that is doing the work. In Grove 3547, the convening team worked to ensure that our participant group was horizontally diverse, including people from all sectors impacted by the challenge, as well as vertically diverse, including people from all levels of the social hierarchy.

The experimental aspect of a Social Lab refers to the necessity for the project to have a rigorous design culture at all levels marked by trial and error, iteration, and ongoing improvement over time. The prototypes of a Social Lab start small and grow in scope and scale over time, as they can demonstrate effectiveness.

The systemic aspect of a Social Lab means that the project is trying to impact the whole system at the level of root causes. The social challenges at the heart of the work are seen as embedded in context and a part of an ecology of intersecting economic, political and cultural forces that make intervention a delicate and difficult matter. Participants are asked to think differently about, and to look deeply into the system they want to change, including conducting their own ethnographic research as part of the project.

The project as a whole was loosely divided into five overlapping, and loosely defined teams: The Roller team, the convening team, the hosting team, the participant team, and the prototyping teams.

The Roller team consisted of those on Roller Strategies’ ‘core team’ who were working on The Grove, including one full-time team member who was “on the ground,” living on the South Side.

The convening team consisted of high-level leadership and program officers at The Trust, and high-level leadership and project management level staff at Roller.

The hosting team consisted of most of the people on the convening team, as well as local facilitators, communications professionals and filmmakers, community liaisons, organizers, and support staff.

The participant team was made up of those who were invited to participate in the project through a process of broad and inclusive community outreach. This team included local activists and nonprofit leaders, program managers and innovation professionals from the Trust, local business leaders, small business owners, youth and residents of the South Side at all levels of social strata.

The prototyping teams were five teams that self-organized out of the participant team according to the themes and challenges that emerged during the project’s kickoff workshop.

Chicago In Context: The Loop And The South Side

Chicago is a city of almost 3 million people, with 22 miles of coastline along the shores of Lake Michigan. It is a very diverse city with about ⅓ of its population being African American, Latino and Caucasian respectively. However, Chicago is also one of the most segregated cities in the US, the South Side being predominantly African American, the West Side being predominantly Latino, and the North Side being predominantly white.

This segregation is not random but is the consequence of Chicago’s long history of settling, relocation, migration, displacement, and housing policy. Chicago history is marked by an effort to intentionally segregate the city along racial lines by powerful white elites in the late 19th and early 20th Century.

Chicago’s downtown area is known as “The Loop” because it is surrounded by a loop of elevated rail trains, as well as the Chicago River that geographically mark it as separate from the surrounding neighborhoods or “Community Areas,” of which there are 77 in the city.

The Loop is known as the center of power of Chicago. It’s where the money and political power are geographically situated, home to Chicago’s government, large banks, exchanges and financial institutions, dozens of foundations, a number of universities, and the city’s largest commercial districts. “The Loop” is often used synonymously with power and influence in Chicago.

At 225 North Michigan Avenue, in the northeastern section of the Loop, you can find the Chicago Community Trust, a 100 year old Chicago foundation that funds local programs, arts, culture and education across Chicagoland, including the project that this case study explores in detail.

South of the Loop, and far south of The Trust’s offices, can be found a large group of about 40 community areas collectively and loosely referred to as the “South Side”. The South Side of Chicago is overwhelmingly African American with the exception of Hyde Park and some neighborhoods on the South West Side, which are very diverse.

The South Side is also home to a tragic epidemic of gun violence. While living in Chicago, members of the Roller team witnessed gun violence first hand, including gunshots heard in close proximity daily, frequent arrests, and pervasive police and emergency services presence, especially during the summer months. The team also heard first hand stories of the widespread impact of gun violence and policing, and saw and heard that the youngest residents of the South Side bear the weight of the epidemic.

While this narrative of gun violence is true, it is not the only narrative of the South Side. The South Side varies greatly from neighborhood to neighborhood in terms of safety, affluence, and culture and is home to long-standing communities, generations of families, churches, arts organizations, universities and businesses. Many South Side neighborhoods are marked by thriving local economies. The South Side is also home to a very large number of small, non-profit organizations locally referred to as Community Based Organizations (CBOs). The Roller team encountered a local spirit of activism, community and support that was in many ways the most visible aspect of South Side culture.

Even so, the stark segregation between the North and South Sides in Chicago is striking. To some newcomers to Chicago on the Roller team, the distribution of race and capital in Chicago resembled a form of apartheid. As we will see below, the stark difference between North and South in Chicago plays out at multiple scales.

Chicago’s Contested Narrative Landscape: Violence in the Windy City

There are two common and contested Chicagoan cultural narratives that preceded and informed the arrival and acclimatization of Roller’s team in Chicago: those regarding violence and politics.

1) Cultural narratives about Chicago focus on violence: Chicago is a place where people get shot. Thousands of people every year. The majority of people who are shot in Chicago are young people of color, who live on the South and West Sides.

One person the project team encountered in his mid-twenties from the South Side, noted that many of his closest friends from high school had passed away, victims of gun violence. He went into the military as a means of accessing opportunity and getting out of the South Side. He said he felt it was safer to go to Afghanistan than to stay home, and that surviving into one’s mid-twenties in Chicago was a feat to be proud of.

The news stories about gun violence in Chicago pile up daily, weekly and monthly, feeding incomprehensible statistics. These are mostly very short, unemotional news stories that present the simple facts: Who was shot, why they were shot and by whom (if known), where on their body were they shot, where they were when they were shot, if they made it to a particular hospital or not, and whether they were murdered or survived the shooting. These short snippets often come in lists, one news story covering multiple shootings.

The stories about—and impact of—violence in Chicago are everywhere. However there is also a sense among residents that the narratives about the South Side’s violence are driven and entrenched by news media rooted in the political and economic power center of the Loop. Political will and economic support from the Loop are seen as limited, with policies often undercutting and underfunding important work that is being done to address the challenge of violence. Meanwhile violence is sensationalized through media coverage, helping to entrench racial bias across the city. This reinforces cultural narratives of the South Side as a desolate and broken community stuck in a cycle of violence. While the South Side is a dangerous place, and parts of it are in dire need, South Side communities are working tirelessly to address the challenges in their neighborhoods. Meanwhile, frustrating and widespread racialized narratives of violence still dominate the larger Chicagoan discourse.

2) Cultural narratives about Chicago focus on place-based politics: Chicago is a city of ruthless local political culture. From politics and government, to the nonprofit sector, business, the culture of gangs, and even friend groups, Chicago is known as a place where people are engaged in politics. This political culture is part of the reason that Chicago is nicknamed the “Windy City”, referring not only to the weather but also to how much people advocate for their interests.

From one vantage point, this political culture is viewed as a culture of collaboration in which words are rich with meaning, and gestures of shared agency and cooperation can be seen as a kind of currency. However, when miscommunication happens, or when people refuse to collaborate, share agency, or co-create narratives, actors often resort to power and influence, attempting to control which narratives are at play at which particular points of agency in the system.

Before the project began, the Roller leadership was warned by players inside and outside of Chicago to “be careful”, and was wished “good luck” navigating the complex political landscape of Chicago, which to some degree shaped their mindset at the outset. The Roller team was careful with its words, entering into a political culture seeking to temper or influence narrative even before arriving in Chicago. Expectations can shape realities. Prophecies can self-fulfill.

However, this narrative of Chicago as a place of intense political culture and contested narratives, is itself contested in Chicago. One member of the Roller team experienced this culture of contested narrative as “hidden in plain sight”. It’s a culture of collaboration and partnership, accompanied by its opposite: competition, secrecy, and political maneuvering. All agree to cooperate, while all play for position. Depending on the context, speaking plainly about power in Chicago can be taboo.

In general, the narratives that are attributed to the South Side—and Chicago as a whole—are contested, reflecting the landscape of contested political and economic power across the city. The North/South dynamic of the Loop and the South Side plays out at all scales along cultural and economic lines.

In this context, to reshape the narratives of Chicago, of North and South, of race, place and belonging—to forge new alliances across boundaries—is to reshape the political landscape of what’s possible in the city.

PROCESS: A MIXED METHODS APPROACH TO ADDRESSING COMPLEX SOCIAL CHALLENGES

In carrying out the first phase of the Social Lab, the partnership employed a number of methods including demographic and statistical analysis, network mapping, ethnographic and qualitative research, systems thinking, Agile project management, Lean product development, rapid prototyping, and participatory design.

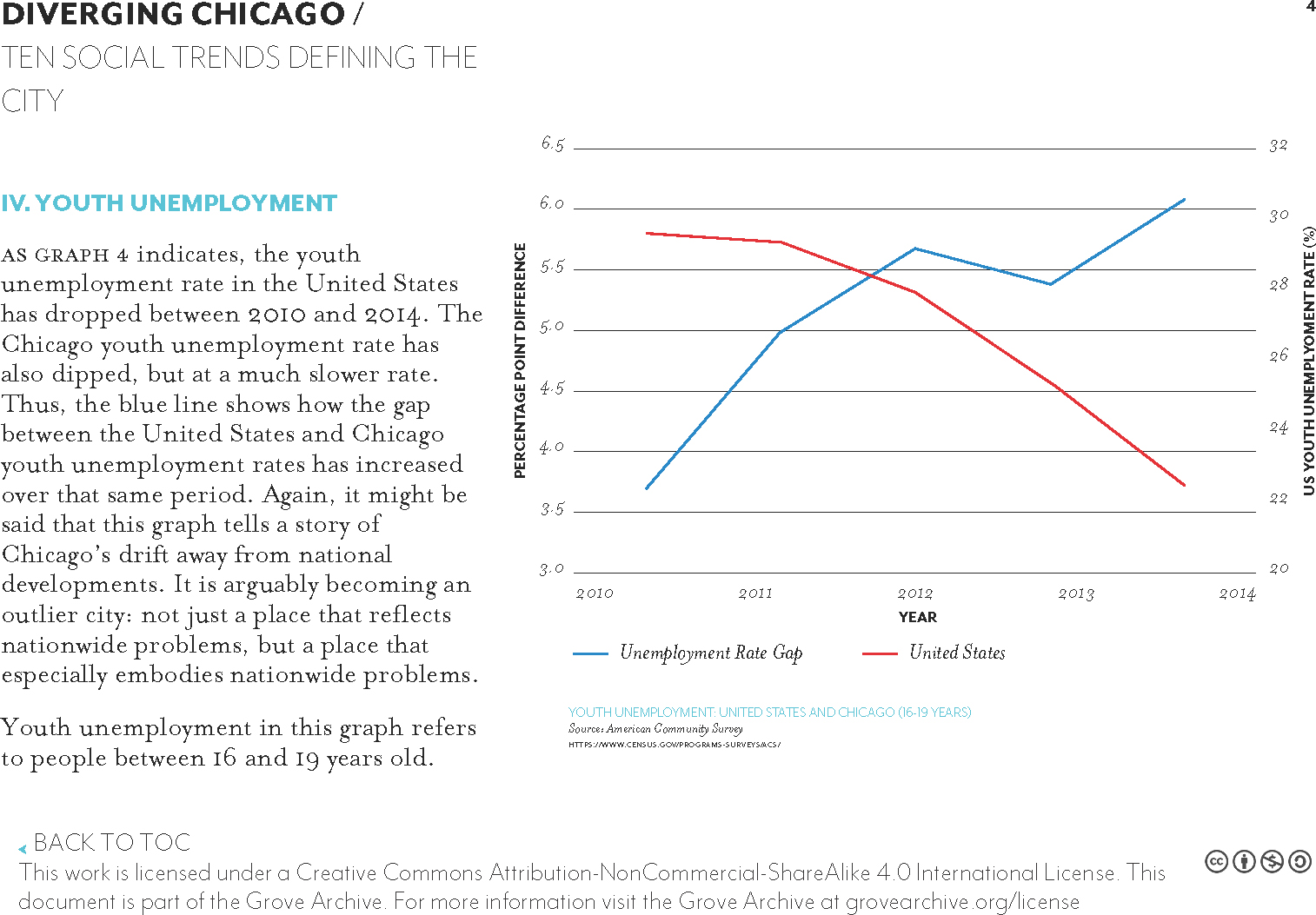

Demographic and Statistical Analysis

Roller worked with researchers in their network to develop a set of initial data, documenting the intersection of very broad trends across Chicago over time. Data was found and compared regarding income disparity, welfare, race, population, urban mobility, housing prices and other factors. This research, while sourced responsibly, and effective at painting an overall picture, was employed by Roller as evidence of the necessity for the Social Labs approach. The data set was branded Diverging Chicago: 10 Social Trends Defining the City, and presented as evidence of a set of urgent and impending crises in Chicago necessitating intervention. Participants in the Grove and some of the courses delivered as part of the project, appeared wary of this branded data. They questioned the sources, and asked where the research had come from and who had conducted it. Some participants dismissed it outright, while others appeared to be very interested in what the data implied.

There was a sense that participants had a healthy skepticism regarding the data. There was a tension between the perceived “actual” data and the perceived “presentation” of the data. Chicagoans were protective of the narratives of their city, defensive against cliches, projections and generalizations, especially coming from outsiders. For example, one participant contested the idea that these social trends “defined the city”, as the name implies. Still, participants were interested in data that would deliver insight into how to more effectively address the challenges facing Chicago, and willing to look past a certain amount of rhetoric in the interest of social impact.

Figure 2.

Network mapping

During the convening phase of the project, Roller and the Trust engaged in an extensive network mapping exercise to analyse the reach and diversity of the Trust’s local extended networks. Because the project aimed to have a systemic impact, shifting dynamics in the system across sectors and demographic boundaries, it was necessary to look at the reach and constitution of their network. Using an online tool called Kumu, Roller and the Trust mapped it’s networks, starting with grant recipient and partner organizations and other foundations, and then expanding the maps by degrees of separation, and by sector.

This network mapping process was then updated and integrated as the ethnographic interviews added data points to the map. Interviewees were added to the map, and they often offered the project team access and introductions to their own networks, acting as gatekeepers to expertise or demographics missing from the diversity of the project.

The network maps helped inform the project in a number of ways. They allowed the project team to assess where network blind spots were, informing outreach, marketing, and recruitment efforts. They were also able to show where overlapping connections were, enabling more-effective networking, as well as informing the storytelling approach to recruitment. Because of the at-times delicate political culture of Chicago, it was necessary to be careful what was revealed to whom at what time. Recruitment, invitations, and messaging was an important part of the process, and who knows whom would be an important factor informing the convening process.

Multi-stakeholder convening

In order for a Social Lab to represent a truly systemic perspective and have a systemic impact, convening a diverse stakeholder group is crucial. For this reason, one of the core aims of a Social Lab during its initial phase is to convene a microcosm of the system. A participant team that is a microcosm of the social system means that all of the different sectors, groups and levels of power and agency in the system are represented.

Figure 3.

This ensures that the insights, conversations and outputs of the projects are not able to be co-opted by any single perpective, thereby running into unexpected resistance later on. In other words, by including the full range of perspectives present in the system in a participatory process, the prototypes and outputs are pre-vetted. The system works out some of its challenges and tensions in the microcosm of the Lab so that when initiatives are piloted and scaled in the system as a whole, they have already been subject to a broad range of scrutiny. This process is amplified by inviting guests, allies, advisors, and challengers from an even broader range of actors into the Lab to vet and give feedback on lab team prototypes.

Semi-Structured Dialogue Interviews

Over the course of two months, the project team conducted 42 semi-structured biographical interviews with a horizontally and vertically diverse group of Chicagoans. The interviewee selection process was connected to the network mapping process. Interviewees were chosen first from the Trust and its grantees, then from its wider network. Interviewees from these initial interviews were asked to suggest people whose perspective should be included in determining the course of the project. As the project team continued this process, the pool of interviewees expanded to include a very diverse group of Chicagoans far removed from the Trust and its network.

Each individual interview was structured as follows: After briefly and generally introducing the scope and aims of the project and the Dialogue Interview process, interviewees were invited to tell their life stories, starting at the beginning. The introduction of the project and interview process would generally provide enough context that interviewees would structure their stories to content that was relevant to the project. They would keep their interviews broad enough, however, to include details of their personal and cultural experiences living through and engaging with the context, challenges, and nuances that the Social Lab was seeking to address and navigate.

Going through this process with such a diverse group of interviewees provided a very broad and very detailed set of data to work with. Once they were all complete, the interview teams went through two inductive “interview processing sessions”, in which relevant and anonymous quotes were gathered en-masse and then grouped according to themes and issues.

This process yielded a broad and subtle cultural and historical landscape of the issues facing Chicago and its citizens. The findings were distilled into an extensive report, which the Trust ultimately decided not to publish publicly because of the gravity and sensitivity of some of the content.

Participatory Ethnography and Qualitative Research

Ethnographic research is a central element in the Social Lab that is present throughout the process, clumped into activities called “sensing work”. In addition to conducting Dialogue Interviews, the project integrated “participatory ethnography” into the process, training Lab participants in semi-structured interviews and participant observation. Participants interviewed each other, pairing with people from different levels and sectors of the social system, to leverage the diversity of the group and expose participants to perspectives different from their own. “Learning Journeys” were also organized, giving participants the opportunity to conduct site visits to various points of interest throughout the system. Participant groups conducted participant observation at a Juvenile Detention Center, City Hall, a non-profit working with youth on civic engagement, an “L” train going all the way from the South Side to the North Side, and visited a local cultural historian in Bronzeville.

By building participatory ethnographic research into the Social Lab, the project team aimed to bridge the divide between researchers and subjects, and offer a deeper level of transparency and agency to the participants in the project. The project team reasoned that those embedded in the social system would have a deeper level of access and legitimacy and would be able to conduct the most effective research and outreach. Rather than “outsiders” doing the research, the project team itself would engage deeply with the system.

Systems Thinking

On the second day of the kickoff workshop, participants went through an extensive systems thinking process. This began with a conversation about the issues facing the South Side of Chicago, followed by a creative brainstorm of possible social interventions and solutions addressing the question: How can we create resilient livelihoods, in Douglas, Oakland and Grand Boulevard? (These were the three neighborhoods in Bronzeville, and the question driving the project).

The brainstorm was then distilled into focus areas through a clustering process, yielding a map of the social challenges facing the South Side and a diverse set of potential ideas for solutions. Participants further refined their ideas by voting for the ideas with the most urgency, potential impact, and what they had the most energy to do. This process also yielded ideas for how issues could be approached from a number of different angles at once, and how ideas might overlap and combine to have systemic impact.

This exercise and it’s outputs in part determined the course of the project as a whole, as participants formed their prototyping teams around these issues and ideas for intervention.

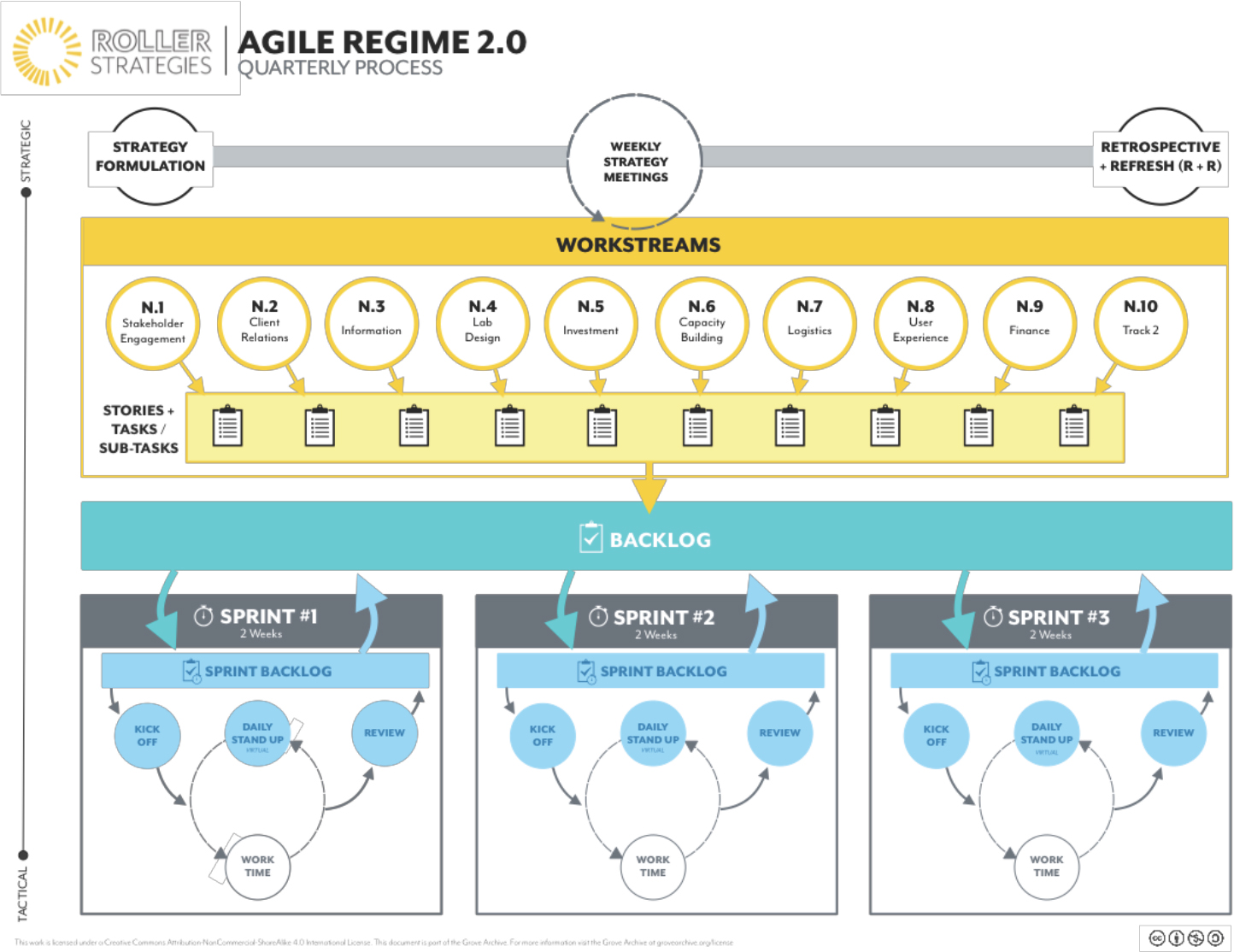

Agile project management

Agile project management was used to manage and inform the logistics of the project. Agile is a way of working that can support multiple loosely defined, coordinated teams, working in planning cycles or “sprints”. Sprints can have varying durations depending on the needs and context of the project. These activities and teams are coordinated so that the strategic thinking, decision making and tactical operations are coordinated, and allow channels of communication and feedback at every level.

Agile is also marked by review and iteration. The teams hold meetings to assess the effectiveness of their work towards project goals, as well as the effectiveness of their Agile planning process, and then to plan their work based on the learnings from their review process, enabling adaptation over time.

Agile as a project management system was generally helpful to Roller. Considering the many moving parts, multiple overlapping teams, and complex sets of relationships in the project, having a system for managing workflows proved invaluable to those inside Roller. However, those on the participant team and in the Trust did not see as much value in the use of Agile. On the contrary, some people found the Agile language of “sprints” and “workstreams” as unneeded added complexity and confusion. Some of this was due to the (aesthetically painful and confusing) way in which the Agile process was represented:

Figure 4.

Rapid prototyping & Participatory design

The project’s use of design thinking took shape in a two specific applications. Rapid prototyping was used during the kickoff workshop to generate and refine a large of number of potential ideas for social interventions, and a more ongoing participatory design practice was initiated as the prototypes were launched and engaged further with community.

During the Kickoff workshop, the prototyping teams met and began to explore through model-building what they might actually do together to support the livelihoods of young people in Bronzeville. This model-building process, involved using Legos, pipe-cleaners, playdough and other materials to make models representing the real-world programs or institutions they intended to prototype. Once the models were built, each team had an opportunity to present their model to the rest of the group, answer clarifying questions and receive feedback on their models. They then made changes based on the feedback and developed new iterations of their prototypes.

As the project teams developed their ideas into subsequent workshops, they utilized participatory design principles, taking their ideas out into the community and engaging with the target demographic of their unique project. Depending on the response, some teams took more time to refine their ideas, try to new ones, and do further research with the community, while other teams began to launch small pilot versions of their projects.

Throughout the course of the project, teams utilized participatory design and sought user-input, through ethnographic and qualitative research, community outreach, online ad testing, and principles from design thinking and Lean product development.

Social Labs Framing

The above methods as well as other tools and approaches were conceptually organized according to the Social Lab’s top level categories, or “stacks”: innovation (the facilitated processes through which teams learn, prototype and respond creatively to the challenges of the social system), governance (the organization of the project as a whole and management of power, accountability and transparency), information (internal and external communications, including knowledge sharing and collaboration infrastructure, and project-wide storytelling), and capacity (training staff and participants in the theory, methods, tools and skills related to the delivery of a Social Lab).

While capacity building processes took place throughout the events of the lab, one of the core ways that the Social Lab approach was supported in the system as a whole was through the delivery of a series of courses or “masterclasses”. The masterclass was a strategic-level course on the theory and practice of Social Labs, offered primarily to local leaders and stakeholders who were close to the Trust’s professional networks.

THE “COLONIAL MOMENT” OF SYSTEMS CHANGE: NORTH/SOUTH & INSIDER/OUTSIDER DYNAMICS

Development anthropologists reinforce ethnocentric and dominating models of development. Moreover, these practitioners disturbingly recycle, in the name of cultural sensitivity and local knowledge, conventional views of modernization, social change, and the Third World. (Escobar, 658)

This section will examine specific points of contact between institutional, identity and cultural groups in the project, and how those points of contact are informed by interest and cultural narrative.

Some of the most poignant challenges that arose during the course of the project came about because of perceived similarity and difference and the formation of groups around both formal and informal lines. Formally, these dynamics played out between the different teams of the project. Informally, groupings and tensions emerged around “localness” and proximity to “the community”, socioeconomic status, race, age, institutional affiliation, nationality, and “expertise”. At the points of contact between these various groupings and identities, complex dynamics played out as actors and groups vied for power and agency in regards to the project and the broader social system.

These points of contact and the complexities and tensions at their intersections contributed to an “insider/outsider” dynamic that played out at different scales of the project, as well as a tendency to mobilize evidence for the purposes of group interests. This had a strong impact on the trust and strategic alignment of the project as a whole.

“Localness” And Agency

Power in the project was distributed along both economic and cultural lines, with high social capital accompanying the “localness” of a person or institution. To be “born and raised” in Chicago is an emblem of belonging and status in Chicago, and even those who have been there for decades would hesitate to say they were “from Chicago”, instead saying they were “relatively new” to the city. On the contrary, to be an “outsider” seems to bring an air of unfamiliarity and even illegitimacy. To be an outsider in Chicago is to be questioned as to why you’re there.

Another expression of the power of “localness” was “proximity to community.” In this case, “community” generally referred to those actors and institutions that were situated in Bronzeville, and specifically those that were working in the social sector. One of the only points of unanimous agreement among the Convening team was that the project was meant to be “community-driven”.

That the institutions funding and setting the overall strategic direction of the project were nowhere near the South Side, was recognized as ironic and problematic by participants, as well as some Roller and Trust staff.

While community agency was the agreed-upon goal of the project, the organizations leading the work vied for power to define and control what that would mean in terms of agency. This played out in disputes and power plays between the Roller team and the Trust in regards to the scope, timeline, composition, access to information and resources, and the process and structure of the project as a whole. So while the whole project team agreed that agency should be situated in “the community,” plays for power were often justified with degrees of “localness” (who is “more local” than whom), and/or claims of representing the community’s interests. One of the Trust’s high-level staff commented:

The consultants would say “the community knows best”, but they didn’t believe that the community institutions knew best. They over-rode our decisions every time. If we had had more time, we could have built a local team. We did not put community first.

While the Trust sees itself as a “local” institution and therefore in a legitimate position to diagnose and address the social ills present throughout Chicago; on the South Side the Trust represents the power and influence of the Loop and is seen by some as an “outsider” to local structures and systems. On the other hand, Roller saw itself as holding expertise in grounding collaborative work in the agency of community, judging that they could actually help the Trust do a better job of leading “community driven” work.

Foundation Culture Vs. Community-Driven Social Impact

This section explores the power dynamics and cultural tensions between the foundation funding the work and the local South Side communities and organizations involved in the project.

The Chicago Community Trust is situated on the 22nd floor of a massive skyscraper in the Loop. It’s a smooth, black cubic structure, beautiful and almost frightening in size. The building smells like power. 225 N Michigan is guarded by a set of automated gates with a barcode scanner, preventing anyone without an invitation and a photo ID from accessing the elevator. Those who work there on an ongoing basis may get clearance, visit the security offices for a photo, and get a permanent key card giving them access to the building. An infrastructure of security protects the building, seemingly keeping the world out, and also keeping the office workers in, embedded in their world. While the gates would frequently malfunction, giving off a loud, horn-like alarm sound, there was still a clear “inside” and “outside” to the Trust. Even on the 22nd floor, a visitor needs their keycard to enter the offices themselves, or they must resort to waving down a passing office worker through the huge glass wall that keeps out those who don’t have access.

The Trust, like many foundations, also has a corporate culture, with a strict dress code (casual Fridays are in place if one cares to wear jeans), and a tight-knit bureaucracy of grant requirements and programming, carried out by a large team working out of cubicles, private offices, and co-working space, depending on one’s position in the organization. These cultural and organizational rules and channels essentially act as filters and gatekeepers for those seeking to do business with the Trust. Those that interact with the Trust do so on the Trust’s terms.

The Roller team was critical of this, wondering if 18-26 year olds from Bronzeville would be welcome in the Trust’s offices as they were, or if instead would they be required to fit in to a culture of bureaucracy, follow a dress code, and show that they meet grant requirements? In other words, the culture of the Trust itself begged the question:

In the context of power and resources that are centralized in the Loop, and guarded tightly by a securitized and bureaucratic corporate culture that goes so far as to manage dress, how can a diverse, community-driven, participatory project directly and effectively engage 18-25 year old youths on the South Side?

In this way the Trust was experienced as “overly-secure” and “inaccessible to the outside world” by members of the Roller team. This experience was cultural, physical and relational. Although the Roller team was warmly welcomed, and had access to the people and the offices of the Trust, they nonetheless often felt out of place, like visitors in a very particular brand of corporate culture, trying to “do things right” and laughing about how difficult it was. If even the Roller team felt out of place, what about the young people our project would engage with on the South Side? Was this cultural dynamic a Chicago/Outsiders thing, a Loop/South Side thing, a Funders/Recipients thing, or all of the above?

The “North/South” dynamic between funders and recipients proved to be a complex one, in which proximity to the institutional power and resources of the Trust was both a currency for, and a hindrance to locality and community-driven agency.

In one instance, members of the project team were canvassing South Side neighborhoods recruiting individual and organizational participants. They entered a local CBO without calling ahead, described the project and explained that they were looking for participants and collaborators. The team was met with a string of curt and very direct questions, including “Who’s funding your project?” (“The Chicago Community Trust.”), “Are you looking for funding?” (“No.”), “Is the project already funded?” (“Yes.”), and “Is there funding available for participants?” (“Yes.”). Upon hearing the answers to these questions, and within 15 minutes of having walked in the door, the team was invited into a back room to sit down with the second-highest person in the organization’s management, who proceeded to offer a great deal of support and recommend a number of their organization’s young leaders for participation in the project. Proximity to the Loop and its resources acted as valuable social currency, allowing the team access to networks and people that would have been very inaccessible otherwise.

While proximity to the Loop and the Trust acted as a kind of currency, there was also an air of mistrust between these different cultural and geographic spaces. At times the project team heard participants remark that local institutions and foundations (including the Trust) would make promises they couldn’t keep, and had a reputation for de-funding effective programs. Some participants expressed doubt that the Grove would continue to be funded beyond a few months, anticipating that their work would be cut short. There was both great enthusiasm, as well as a general air of skepticism among participants from the beginning.

The problematic dynamic and narrative of the Loop as a source of power and funding and the South Side as a recipient of funding and programming, is also played out in the relationship between Foundations and CBOs. Leaders of CBOs that were part of the Grove were both frustrated by the bureaucratic requirements of grant-giving organizations as well as driven by the scarcity of funds available. That CBOs were forced to use large portions of their scarce resources on grant-writing and meeting the requirements of the funding organizations (rather than on programming), was an oft-cited point of contention. CBO leaders expressed frustration that they were further scrutinized as to how much of their budget went toward programming rather than management and overhead. There was a two-way squeeze in order: requirements to meet cost-intensive grant requirements, and to prove cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of the CBO’s operations. CBOs were in some ways sacrificing their impact in order to meet the “nonprofit bottom line” of funding requirements and impact assessment.

Part of the Social Labs model—aimed at combating the power discrepancy regarding funding—is to make funds available “up-front” so that participants and prototyping teams have access to resources without strings attached. The innovation fund was a pot of money that would be set aside for the prototyping teams to access freely to fund their prototypes. $100,000 total was to be split up and/or spent by the teams as they decided best. It was in their control.

But when Roller requested of the Trust that they transfer the $100,000 to a bank account that would be outside the Trust’s control, a key point of dispute became visible: The Trust’s internal policies would require a detailed budget, with very specific costs breaking down exactly what the funds were to be spent on, as well as detailed reporting essentially “proving” that the planned budget was working to impact the challenge.

The culture of the foundation was one of tracking, planning, and linear thinking. The point of the Social Lab is to navigate the constantly changing terrain of a complex social challenge with agility, creativity and collaboration, maintaining the freedom to change course rapidly. A process combining ethnography and design would allow project direction to shift immediately with prototype feedback, and would allow project teams to use funds try out new and different ideas that might learn from failure. The whole point was to provide an open space to try creative ideas. The funding had to come first.

This was a pivotal moment for the project. The Trust’s leadership were up against their own internal mechanisms and policies and some were skeptical as to the necessity of having funds come first.

The Trust, displaying a profound commitment to the project and a willingness to challenge its own boundaries, convened a special meeting of their leadership and board, and changed their policies to allow for a new type of funding that would allow teams to prototype. This was seen by most everyone involved as a heroic leap in the right direction. This moment was marked by a great deal of discomfort, excitement, and energy on all sides. Some at the Trust, however, remained skeptical of this exceptional decision until mid-way through the first design studio.

A number of the Teams were preparing to set up their weekly meetings and were confirming everyone’s contact details. One team member, however, was unable to participate because he didn’t have a phone, and another was out of minutes. There was no way that the teams could coordinate without a way to contact all of the team members. Someone suggested that the team simply dip into their budget and buy their team member a phone. This was a very sticky issue. “Shouldn’t the funds be spent on the prototype?” “Are we allowed to spend the money this way?” The decision was challenging a few core assumptions, all of which related to power and what was “inside” or “outside” the scope of the project.

Some of the assumptions being challenged were: That the money available still belonged to the Trust and not to the project team; That the social system (and the challenge) was “out there” and so funds should only be spent “out there”; and that the “private” and “public” lives of participants should be kept strictly separate. Ultimately the participant team came to understand that it truly had agency over the direction of the project, and that the challenge was operating at a level of depth close to home. The decision was made to buy the phone.

At this moment, something shifted for a number of participants, including Trust staff. There was a visceral understanding that entrusting the participant teams with resources without accounting for every budget line item actually encouraged the accountability and collective agency of the entire project by entrusting all of the participants equally with the power to make decisions with fiscal repercussions. The Trust, by giving up its power to control and make final decisions, entrusted the participant group with that responsibility and enabled a culture of shared power and agency. Within an hour, everyone had a phone. The implications of this fact for the project as a whole were staggering. See a need? Meet it. The project realized itself as truly community-driven, and responsive to the immediate situation on the ground. If this was possible at the drop of a hat, what was possible at scale over the course of a years-long lab?

In these ways, the project was experimental at every level. The Trust was experimenting with new funding models, and the participants involved were experimenting with new ways of impacting the social fabric. But the project was not without its divides.

Formal Structural Agency

The practical concentration of agency in the project was in part shaped by the formal structure of the project. As mentioned above, the project was organized into teams. These teams notably and problematically corresponded to different levels and different forms of agency and power.

The convening team, for example, consisted of strategic players at the Trust and in Roller who collaborated to design the research, timeline, facilitation agenda, convening, staffing and composition of the project.

The hosting team, while not formally involved in setting the strategic direction of the project, was involved in designing the agendas for the specific workshops and events that composed the project, as well as actually facilitating the workshops. Being in charge of facilitation also meant being able to change and adapt the course of the workshop and thereby the direction and timeline of the project.

The participant team and the prototyping teams that they formed were not directly involved in the workshop design process or overall strategy, but they did have a great deal of agency in terms of the content of the project and the nature of the work being done in the social system. These teams were the ones “on the ground” and “in the community” doing the actual work of the Social Lab, and they had unilateral control over the content of the project, that is to say, over the design, delivery and strategy of the actual prototypes and projects that were launched and adapted during the project.

The agency of the prototyping teams was not “anything goes” however. There were criteria for the prototypes (designed to ensure quality and impact), that were conceived and agreed upon at the highest level of the project. The Convening Team was basically in charge of the container and the process – designing and facilitating an effective process that would allow for the launch of scalable community-driven social interventions that would have maximum impact. The participants and the Prototyping Teams were in charge of the content of the project’s outputs: conceiving, designing, launching and iterating the social interventions in collaboration with community.

While it’s not clear whether there was any inequality in the amount of power or agency available to these different tiers of the project, the quality of that agency was definitely different. The Social Lab acted as a bridge between “the local” or “the community” on the one hand, and the “moneyed institutions” or “the system” on the other. It acted as a tiered bridge between the Loop and the South Side. In this way, the Social Lab’s job was essentially to ensure that power was concentrated in “the community” even as resources flowed from the center of power. This was easier said than done.

“Expertise” Vs Local Knowledge

While the process of the overall Lab was determined “from above”, the prototyping teams also had agency in regards to process, it was just a specific part of the process: the part that engaged with community. While this agency was real, the convening team had designed the process and the parameters of success independently of the participant team, contributing to an experience by participants in the project that there was “regulation from above” in regards to what was a viable direction to their work.

This regulation from above took the form of codified methods and the presence of outsiders who were presented as experts. For example, at one point during the process Roller invited an outside consultant to teach “Lean” product development as a model for developing and testing initial ideas for prototypes in the field. One participant expressed frustration, because as a professional and entrepreneur, he was quite familiar with Lean, prototyping and design thinking. He expressed that he was totally capable of applying Lean to his work in the community without the need for expensive consultants. He wondered what, if anything, original the “Social Lab” would actually contribute. He wanted to know what exactly is a Social Lab?

Unfortunately that question is a bit hard to answer, because a Social Lab is essentially a practice, rather than a method. The “Social Lab” is not intended to be a defined, codified way of doing things. It’s supposed to be an approach to strategy that draws on principles more than methods. A Social Lab is really any project that’s participatory, creative and iterative, led by a horizontally and vertically diverse team, that seeks to have a systemic impact. Whatever tools and processes will be most effective at realizing these principles can be drawn from.

However, Roller as an organization did codify the practice of Social Labs in a number of ways. One way is directly by publishing the Social Labs Fieldbook, and The Social Labs Revolution, as well as by marketing Social Labs as a practice that requires expertise. In other words, the practice of Social Labs is designed to be inclusive, participative, and open. But if expertise, codification, and technical knowledge are required in order for a Social Lab to be impactful, this will at times conflict with its inclusivity and participatory intention. It risks becoming a form of “colonial” power, expert knowledge form imposed from “above”. There’s a conflict between the participatory and open principle of the Lab and the fact that it requires experts to facilitate it at the strategic level. If codification implies that the rules and ways of the Social Lab must be learned, then can it really be said to be open and participatory?

This problem also has a subtle cultural dimension. In the words of Arturo Escobar: “Communities […] have to adopt organizational forms and project designs that the donor can recognize if they are to have access to project funds, even if those forms may not reflect community traditions.” (Escobar, 674) In other words, at points of contact between those inside and outside the Loop and its institutions, there is a cultural power move at play in which the “recipient” is required to comply with the cultural and institutional forms of the moneyed institution.

In this case, it comes down to how this challenge is addressed when it surfaces in a specific context. From the beginning of the Kickoff workshop, the participant group was invited to give their input and feedback, to tell the hosting team if something wasn’t working. They were assured that it was their project.

But it was also the Trust’s project, and it was the Trust’s project first. And the Trust needed the project to have an air of security and legitimacy. The Trust needs the work to be grounded in expertise. They need a certain degree of codification because in the formal professional context of the Loop (read “North”), codification denotes expertise and expertise denotes authority and legitimacy.

But in the world of community engagement and nonprofit work on the South Side, codification and expertise can easily be seen as a cover for patronization and control. “The community” already knows how to do its business. On the South Side, it is local knowledge and a proven history of community engagement that speak to legitimacy. In this way, the Social Lab is an intermediary seeking to translate and connect those on opposite sides of an institutional power gap. It’s inevitable in this context that conflict and tension will emerge.

The role of the Social Lab in this context is to co-facilitate a process that respects institutional and community interests simultaneously, by holding rigorous standards in regards to both institutional legitimacy and community agency. This requires striking a delicate balance, an open center that facilitates input, dialogue, listening and understanding in both directions.

While this approach is clearly well-intentioned, the danger is that a new form of control replaces the old. Even the idea that the Trust and Roller were enabling or “giving” agency directly to the community is patronizing. At best, these institutions are drawing down their own hegemony, slowly challenging the bureaucratically intensive and hierarchical policies of the philanthropic world. At this constantly moving edge, new forms of community engagement continue to hide and reproduce power inequalities in a rhetoric of participation, while continuing to control and dictate how projects are run. This new form of disguised control allows content to come from the participant team and community, while dictating the processes and forms that define the space of the project more broadly. This means that while agency is shared, the backstop of power and the allocation of resources remains with the Trust and its international network of experts.

While power appears to be “more-shared” in the context of a Social Lab, and therefore constitutes a move in the direction of shared agency, power inequalities are still divided along familiar categories: race, geography, institutionality and access to resources.

Race & Nationality

The hosting team was a melange of a few different groups of people: The Roller team, staff from the Trust, and a number of local facilitators and support professionals. While the hosting team was quite diverse, the Roller team was not, consisting of 90% white people. While more diverse than the Roller team, the team at the Trust was also more white than the participant team. This racial dynamic played out in problematic ways and contributed to an experience of the Roller team and the Trust as outsiders. One participant asked why there were “outsiders coming from England to tell us how to do what we’re already doing.”

Additionally, the participant group was dismayed that so much had been done on the project by the convening team before bringing it to the community. The fact that a great deal of “preconditions” work had been done, including interviews and defining the challenge prior to bringing the whole group together, was received by some participants negatively. One participant expressed that they felt like they were being invited into something that was developed by those on the other side of a power differential.

Furthermore, branding of the project as a “Social Lab” was not well-received by the participant group, to say the least. During the kickoff workshop, one participant said, “Why is it called a Lab? Are we being experimented on by white people?” The Participant team explained that the term “Lab” was off-putting and even offensive for a number of reasons, including the ring of social experimentation, and the history of racist socio-economic policy and political inequality in the city.

The question of “experimentation” brought a degree of discomfort to the Roller team, in part because there was a grain of truth to it. While the Roller team and the Trust were not “conducting experiments” on the participants of Grove, the project itself was a first; it was an experiment. While members of the Roller team had decades of experience in social change projects and Social Labs among them, they had not yet run a project together. Roller as an organization was quite young, and this was its first full-scale project. It was a real-life example during which the team could try working together, see what works and what doesn’t, and prototype their own practices in client and community engagement, facilitation and process design at an almost unprecedented scale.

This “experimental” nature of a Social Lab being run by a new team is not necessarily problematic until you bring in the range of inequalities that are present in the context that the project itself is trying to address. An unseasoned team of non-local, mostly white, international expert-actors; partnered with a powerful Loop-centric financial institution; enter an almost entirely African American community with a long history and rich experience of social engagement; and plan to design and facilitate a process of social change.

In this context, it’s difficult to see how the project would not reproduce racial inequality and problematic power dynamics reminiscent of the “colonial moment”.

For Profit Vs Nonprofit Bottom Lines

Needless to say, there was a palpable tension between people working at the Trust, in Community Based Organizations, and the Roller team. This was also expressed in terms of perceived differences in motivation and culture between for-profit and nonprofit organizations.

For example, there was a sense on the part of the Trust that Roller wanted the project to go ahead at a faster pace than the Trust was initially willing to go. This was at least partially true. Roller leadership expressed concern that if the project didn’t get off the ground expediently, political conflict, disagreement, or drawn out decision making processes could take over, sabotaging the project and its potential impacts. Furthermore, the sooner community members were more deeply involved in the project, the sooner agency could be concentrated at that level of the system. If the project didn’t get off the ground, this would be bad for a number of different actors in the system and for a number of different reasons. Roller would no longer have a project, but perhaps more importantly, a new community-driven project would not have a chance to succeed. While it is not true that profit drives Roller’s core agenda, its survival requires meeting a bottom line, which in turn fuels an agenda to produce work that is effective, timely and visible, and to demonstrate impact and value. At a minimum, for-profit organizations have an interest in getting things done at a pace and with a set of outcomes that enables them to survive as organizations.

This tension resulted, however, in some people in the Trust having an experience of being pressured to move forward, or to move at a pace that was faster than the social system warranted. One of the Trust’s high-level staff commented:

When we brought the Social Labs concept in, we moved too fast. We did not take time. Roller was driven by an agenda to get something off the ground. […] We allowed the goals of the institutions and the consultants drive the project and it ultimately undermined the whole thing.

Another way that this played out was during negotiations over contracts and budgets. There was an ongoing sense that the Trust was questioning the Roller budget and the Roller team in terms of their operating costs. The project budget was large. Part of the Social Lab approach is to mobilize resources commensurate with the size or cost of the challenge being addressed. This doesn’t mean that the budget of the project should be equal to the cost of the challenge, but that it should somehow correspond, be proportional.

Part of the problem is that the nonprofit world is often funded commensurate to the costs of running organizations or programs, not addressing social challenges. This means that there is often literally no relationship between the aims and goals of an organization with respect to social change, and the funding that the organization or project gets. This leaves nonprofits underfunded, but is in part due to the culture of the nonprofit world and its relationship to the philanthropic world.

It’s as if the power relationships in the world dictate relationships. Organizations are like people. They have character, interest. Nonprofits obviously want to get funded. Foundations want to ensure that their gifts are used wisely. For profit businesses want to make money. These are the bottom lines. The whole world has a bottom line. But that’s not actually the whole story. While these interests to some degree dictate the relationships between these organizations and sectors, they often align on what they want. They all want to have an impact in the world. It was in these spaces of alignment of mission that the project found its bright spots, and its impact.

OUTPUTS, RESULTS AND IMPACT

The Five Teams of Grove

This section will explore in detail the five teams and prototypes that emerged from the process, and how they changed over the course of the project.

Bronze Bridge

Bronze Bridge was a pop up recording studio and incubator for musicians and sound artists, aimed at supporting creative livelihoods for youth. This prototype, originally called “Bronzeville Arts Collective”, wished to support emerging artists in Bronzeville. They discussed equipment rental for film makers and designers, co-working spaces, educational programs, art studio cooperatives, art mentorship programs, computer labs and music recording spaces. Eventually, they decided to focus on music as a place to start. The team’s mission stated:

Bronze Bridge aims to support emerging artists in Bronzeville. Young people who graduate from high-school aged arts programs do not have a place to work and refine their skills. Bronze Bridge seeks to create space, resources and tools for emerging artists to turn their craft into a profession. While the overarching goal of the team is to support all artists, Bronze Bridge is starting off with a recording space supporting musicians, singers, spoken word artists and other artists who work with sound. This decision was made in alignment with the team’s immediate skill set and connections in the community to a number of emerging artists in need of space to record.

Bronze Bridge’s next iteration was to set up a pop-up recording studio at the Harold Washington Library and open up their offering to the public. A number of local musicians showed up to the prototype. The team also developed their brand, building a website and setting up advertisements to track interest in different concepts for the project.

Over time, while the prototype showed great promise, this team stopped working together due to interpersonal challenges, disagreements and time constraints on the part of participants.

Bronzeville Live

Bronzeville Live began by connecting young adults and CBOs in Bronzeville. They began by looking at existing community based organizations in the area and their relationship to the young adult they seek to serve. Their team held one-to-one meetings with young men in the neighborhood and representatives of community based organizations and learned two things: 1) Young adults who are unemployed, underemployed and not in school have clear aspirations for their lives, and 2) CBOs are interested in hearing from young adults to inform program design.

They then convened a small group of young adults and community based organizations, inviting them to reflect on their goals, challenges and aspirations. They named this convening “The Re-Write.” Their objective was to identify concrete and immediate opportunities to support young adults in reaching their goals and achieving their full potential.

Bronzeville Live’s mission stated:

Bronzeville Live is a team of residents and community organizations working together to address the challenges facing our community. We are developing and launching a co- design process that brings young adults and community based organizations together to come up with ways that each can support young adults in reaching their goals and achieving their full potential.

This team’s long-term aspiration was to take the project to scale, helping to connect CBOs to young people across Bronzeville.

Bronzeville STEAM

The Bronzeville STEAM team began as “Mentor Mingle”, inspired to help young people in Chicago connect to mentorship opportunities by creating a mentorship app. They began engaging with youth and discovered that while there wasn’t a lot of excitement for a mentorship app, there was a sense among youth of disconnection from place. They found that young people in Bronzeville didn’t have a sense of ownership or involvement in the rich cultural history of Bronzeville.

They found that the geography of meaning for young African Americans in Bronzeville was often marked by the territories of gangs, and locations where violent acts had been committed, rather than the rich cultural history (e.g. of basketball and the Black Panthers) that was also present in the neighborhood. Bronzeville STEAM set out to organize cultural tours of Bronzeville for youth, led by elders in the community.

As their idea evolved, they began interviewing people from Bronzeville who were considered “torch-bearers”. They connected deeply with the “old heads” in Bronzeville who had been involved in the rich cultural history of the area throughout their lives, and found that the history of Bronzeville was too rich and diverse to be encompassed in a cultural tour.

Instead of bringing the youth on a tour of Bronzeville history, they decided to try and inspire youth to participate in making history themselves.

This team’s prototype thus evolved into a project to simultaneously document the cultural history of Bronzeville and empower a next generation of documentarians. They connected youth with elders in Bronzeville, and equipped them with filmmaking and audio gear, giving them the chance to document the old stories of the neighborhood and connect to an intergenerational perspective and sense of place. Participants in their prototype became filmmakers and documentarians, and had a role in creating the cultural history in the neighborhood they belong to.

Bronzeville Surge

This team, originally called “Bronzeville Voice”, initiated their project by agreeing to focus on youth leadership. They began with the premise that if they were to support young people in Bronzeville to create resilient livelihoods, their efforts should be guided and led by young people themselves. They began by creating a survey engaging with youth throughout Bronzeville and asking about the core issues they face in their community and the ideas they have for addressing them.

They next set up a one-day meet-up to engage directly with some of the youth they met when they distributed their survey. During this phase they also attended workshops on youth leadership and facilitation, and met with a number of Community Based Organizations to understand their needs and strategies in engaging with young people. They overwhelmingly heard from young people and CBOs that young people need local, youth-led, safe physical spaces where they can learn, engage with community in a safe way, and feel at home.

At this stage they decided to pivot or radically shift their idea. They decided to launch a physical space to support young people and the other grove teams. They named their new project team “Bronzeville Surge”.

Bronzeville Surge got wind that the historic YMCA building in Bronzeville was up for rent for community-oriented programs, and immediately expressed interest. They did a tour of the space and began meeting there to get a feel for the space and brainstorm what was possible. They played with the idea of fundraising for their prototype and begin launching and testing new programs in the community space. The Bronzeville Surge Team also hoped to host next cycles of the Grove, as well as expand established community initiatives that had already proven effective.

Over time, this team pivoted again, changed personnel, and landed on a more modest idea: a bike shop for youth called “Grove Eco”. One of the team members had experience working in a bike shop and knew the impact that building your own bike can have on youth on the South Side of Chicago.

Many young people in Chicago remain within their immediate neighborhoods, never seeing other parts of the city due to safety concerns and lack of transportation and resources. Building or fixing one’s own bike can be an empowering experience, enabling young people to see the results of their own work and instill a sense of possibility and pride. The bike shop itself provides a safe, focused space with access to skill-building, mentorship and creative community. Bicycles also provide transportation, enabling young people to explore parts of the city to which they didn’t have access.

Restore Bronzeville

Restore Bronzeville, previously known as the Justice/Just Us team, started out with a number of different ideas for how to approach the issue of safety. These ideas came directly out of the Grove’s brainstorming process during the kickoff workshop. One idea was a restorative justice center, another was an art-space and project to melt down guns used in controversial police shootings and turn them into medallions and a clothing brand. Other ideas were collaborations between police and young people including park clean-ups, community gardening, and a game night with basketball and board games. As they narrowed down their ideas, they decided to host a dialogue between youth and police to vet their ideas.

They hosted an event with a number of police officers, mentoring adults, and youth. They all shared stories with one another about what has shaped their lives over dinner, and then explored ideas for how to build a new relationship and community practice around the issue of safety. This team also shared the ideas they had been working on and asked for feedback from the community.

Participants in the event were overwhelmingly supportive of the group’s ideas, but in particular was drawn to the idea of a space and dialogue committed to restorative justice. Community members and the police officers present overwhelmingly agreed that a new approach to criminal justice was needed to heal the relationship between police and the community and to build more safety and trust in the neighborhood.

As the project evolved, this team planned to build a youth-led restorative justice hub. Young people that were engaged by Grove participants would have the opportunity to visit other restorative justice hubs in Washington DC and Oakland, CA to learn best practices and insights from organizations already doing the work. The team would then support those youth to create a local restorative justice hub sensitive to the particularities of Bronzeville’s culture and social issues. The aim of the project as a whole was to explore and build possible alternatives to a broken punitive justice system that fuels the incarceration of black youth.

Measuring Impact: Multiple Capitals

While the impact of the prototypes is self-evident in some respects, measurement and valuation of impact is not easy. For this reason Roller used the “Six Capitals” approach to integrated reporting. The Six Capitals are:

Human Capital: New teams & capabilities

Social Capital: New networks, relationships, and collaborations

Intellectual Capital: New knowledge and information

Financial Capital: New stocks, flows and distributions of money

Physical Capital: New products, services and infrastructure

Natural Capital: Ecosystem resources and access thereto

REFERENCES

Public Documentation Archive

Full public documentation for the project can be found at https://www.grovearchive.org/

Project and Interview Reports

Integrated Report

Interview Synthesis Report

Kickoff Workshop Report

Studio One Workshop Report

Studio Two Workshop Report

Studio Three Workshop Report

Literature

Bourgois, Phillippe.

1996 In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge University Press.

Escobar, Arturo.

1991 “Anthropology and the Development Encounter: The Making and Marketing of Development Anthropology.” American Ethnologist 18(4): 658-82.

Hassan, Zaid.

2014 The Social Labs Revolution. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Malinowski, Bronislaw.

1929 “Practical Anthropology.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 2(1): 22–38.

Mitchell, Timothy.

2002 Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.