In international business ethnography, clients and subjects don’t share the same background. Without an understanding of the underlying factors affecting the subject’s behaviors, data can lead to false home-market based assumptions about cause and effect. Where do we as researchers look to detect meaningful findings in international contexts? Drawing on our decades of international fieldwork, we describe how focusing on culture or cultural differences to interpret differences in workflows and attitudes can sometimes hamper accurate interpretation of observations. We describe through case studies how instead, identifying foundation factors shaping behaviors and mindsets such as market forces, government policy, labour markets, and financial schemas can be the key to insight in international contexts.

Keywords: Ethnography, International, Japan, fieldwork, workflow, products and systems, user research, UX, cross-cultural, personas, culture, cultural differences

INTRODUCTION

As corporate ethnographers conducting international research, we study products and work systems designed in one country in another country. The objective of corporate ethnography is gathering, analyzing, and presenting actionable findings about target user workflows and behaviors to client project teams in order to inform product decisions. In such work, where subject and client are separated by context and country, the lack of shared background means the researcher needs to dig deeper for insights and work harder on explanations. Without an understanding of the context and rules making people’s actions meaningful (Randall et al. 2007) data can easily lead to false assumptions.

In user research, research models for how to frame international fieldwork are limited. One common school of thought is that ‘cultural differences’ are the key to understanding local workflows and attitudes (Lee 2007). However, ‘cultural differences’ as the lens with which to interpret key aspects of local workflows and attitudes does not result in discovering the actionable data we and our clients need. We describe through case studies how a different focus: researching local foundation factors such as business structures, the labor market, market forces, and more, which shape differences in workflows and attitudes in international situations — yields more accurate insights and leads to actionable results. Communicating international research results to clients can be challenging and the paper concludes with aspects of communicating results including why UX personas do not work in international contexts.

A caveat: this paper focuses on researching local workflows and attitudes and their relevant underlying factors. It does not address other topics in international research and design such as language, localization issues, and definitions of culture beyond a working definition.

APPROACH TO INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH & DESIGN

Sources on how to frame international UX research & design frequently discuss the importance of incorporating cultural differences into the product or service (Ferreira 2016, Sun 2012, Nielsen & Del Galdo 1996). International UX commonly references definitions of cultural differences such as Hall’s cultural iceberg model where behaviors and beliefs are visible while values & mindsets are hidden below the water line — “Just as nine-tenths of the iceberg is out of sight and below the water line, so is nine-tenths of culture out of conscious awareness” (Hall, 1976) and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory (Hofstede, 2001) which defines how cultural dimensions such as individualism vs. collectivism affect behavior. However, this focus on ‘culture’ is not very useful to working researchers and designers looking for practical models on how to understand international user needs in order to create products that are useful, usable, and desirable. Furthermore, as we will describe, viewing international workflows, work systems, and attitudes through the lens of cultural differences can at times lead to undesirable outcomes.

Over-focus on cultural differences makes it easy to miss key drivers of behavior and attitudes and can cause errors of attribution

Focus on cultural differences as an explanation for observations can overshadow key underlying factors driving the behavior. For example, Japanese research participants are usually quick to notice visual imperfections and inconsistencies in interfaces. The attitude towards UI imperfection in Japan is, ‘if I can see one problem, it indicates many more serious problems hiding underneath.’ US research participants tend not to place the same weight on visible imperfections: “Guess you guys didn’t get around to that.” This could be interpreted as a Japanese cultural trait towards perfection and visual sensitivity. But focusing on this as a cultural difference obscures a key underlying factor shaping attitudes about product development: the difference in how companies ship products in the two countries. Japanese companies do not budget time or money for fixes or version improvements beyond shipping the product; thus products in Japan do not ship until they are complete. By contrast American companies plan ahead for version improvements and dot releases assuming improvements will be needed. The way Japanese companies ship products has trained the Japanese consumer to expect perfection in shipping products. In this case, it is domestic business strategy, not a ‘cultural difference’, that creates the expectation for visual perfection in the Japanese consumer.

For the client cultural differences are hard to understand and prioritize, and not easily actionable

The objective of corporate ethnology is to detail issues arising from work practices resulting in actionable data that can lead to concrete solutions. Although ethnography excels in describing complex systems to stakeholders, when it comes to international research, researchers tend to both focus on discovering and summing up findings under the umbrella of cultural differences (Graham, 2010, Anderson et al. 2017). This results in three problems for clients. One, the vagueness of the term ‘cultural differences’ can make it difficult to determine solutions. Two, clients have no way of assessing the relative importance of a ‘cultural difference’. How important is this difference? How critical is it that the difference is addressed? Three, cultural differences without a deep understanding of what’s underpinning the difference can sometimes be interpreted as malleable or changeable.

For example, research of Japanese document approval workflow reveals the importance of standardized stylized communication beyond please and thank you when passing on documents. These workplace communications could be seen as a cultural difference in politeness: i.e. Japanese people are polite, and that politeness carries into the workplace. But whether or not Japanese culture is polite is beside the point. What is critical is the role the behavior plays in the workplace, what it signifies (reliability and experience), and how it supports and is supported by the underlying corporate structure. Discussion can flounder on discussing a cultural difference. It can be difficult for the client, once grasping the idea of a cultural difference (“they value politeness”) to understand that rather than politeness, which seems flexible, what the behavior signifies and the underlying business structure is hard-and-fast and must be accommodated in the product.

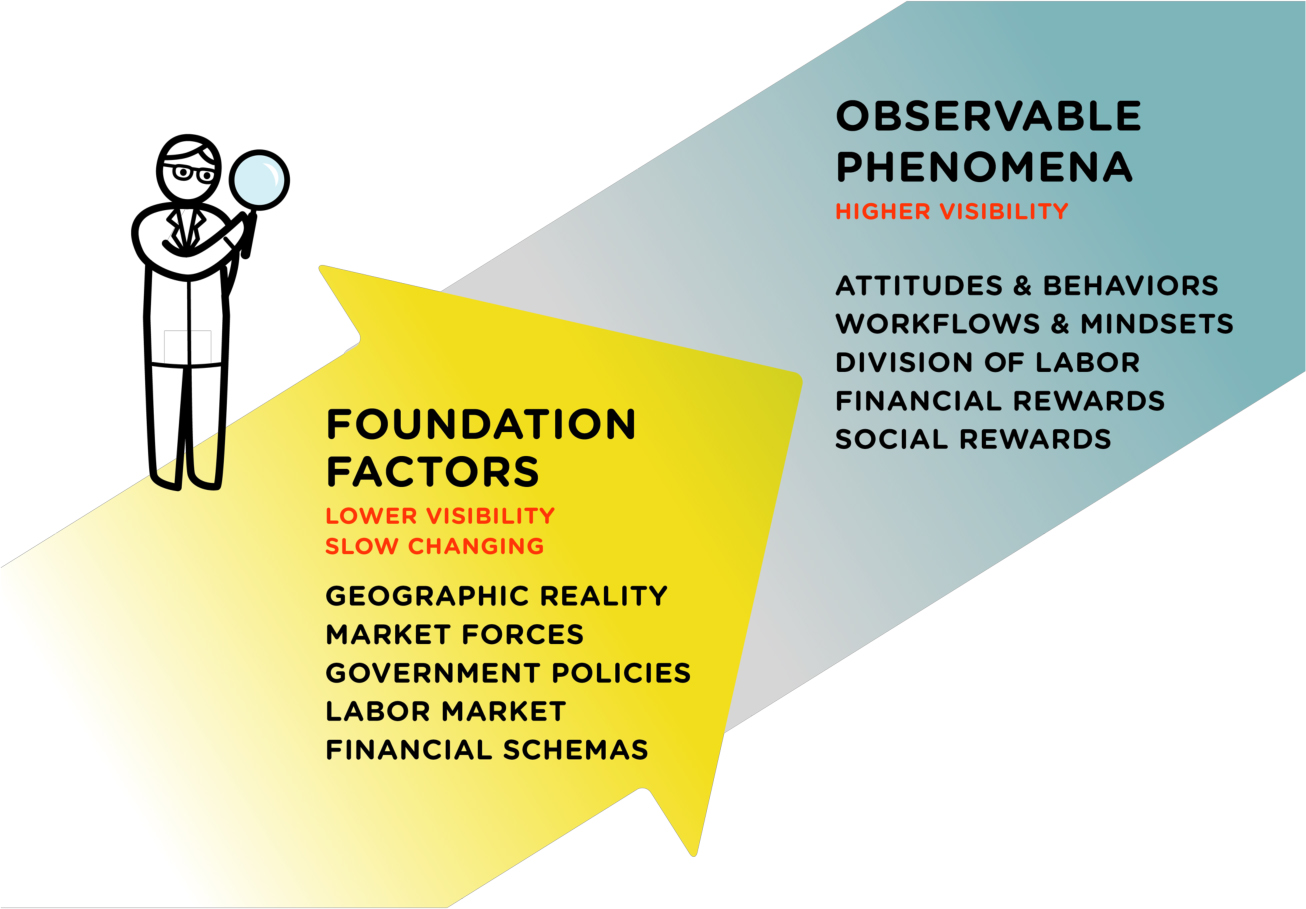

In international research, which often takes place in limited bursts, researchers can jump to cultural differences, which are more easily observable and accessible as explanations, to interpret differences in workflows and behaviors. As Mitchell says, in some approaches ‘culture’ is reified as an explanation and given causal force (Mitchell 1995). We think there is a better way to accurately identify root causes shaping the differences: looking at country and domain-specific foundation factors. What are ‘foundation factors’? These are the near-impossible-to-change factors that shape the evolution of work, motivations, and attitudes; what we might speak of as the ‘givens’ of certain countries and domains. The following are examples of some of the foundation factors shaping workflows, mindsets, the division of labor, what people are rewarded for financially, and more:

- Geographic reality

- Market forces (global and local) such as demand fluctuation

- Government fiscal policy, tax structures, regulations, deregulation

- Labor Market: how fluid is it?

- Social structures: what people are rewarded for socially

- Financial schemas: how business contracts are structured, governance mechanisms such as public-private partnerships

- The design of work: the division of labor, what people are rewarded for financially. Technically, factors above have shaped the design of work, but for simplicity we include the design of work into foundation factors.

Figure 1. Foundation factors shape behaviors, mindsets and more

Foundation factors shape workflows and behaviors, mindsets and attitudes, and individual attributes such as motivations. Much of the behavior or mindsets that could be categorized as cultural is in reality the logical outcome of the foundation factors shaping the situation. Thus, researching the foundation factors underlying international situations can lead to valuable insights on workflows and mindsets that might otherwise remain opaque. For example, the fluidity of the labor market plays a large and unexpected role in shaping day-to-day knowledge-sharing behavior amongst train depot workers (Case Study 1, below).

Foundation factors are important to bringing into the open hidden assumptions based on home context

Client understanding naturally tends to be based on their home context. In order to communicate the facts of observed differences and have them understood, the international researcher must include descriptions of the shaping factors. Without an understanding of the local foundation factors, it is all too easy to develop false assumptions about cause and effect based on the home context. When stakeholders do not have the same baseline understanding of local factors, interpretation tends to be based on the home underlying factors. What could go unsaid or unexplained or unresearched in a domestic context, must be researched and explained in international research.

Without the explanations offered by foundation factors, some findings can be taken too lightly

In international fieldwork, findings on workflows and behaviors that aren’t accompanied by explanations of the key foundation factors shaping the behavior run the risk of being interpreted as open to change. Naturally extrapolating from their own home-country experience, it’s easy for clients to think attitudes can be changed; behaviors can be encouraged; workflows can be re-defined. With a clear understanding the underlying forces shaping the situation, the client can see what can be controlled, and what can’t.

In the first case study below, the initial client assumption is with the right system improvements and some encouragement, European workers will embrace the computerized system. The researcher’s identifying the foundation factors shaping the respective behaviors is key to convincing the client that the behaviors are based on identified intractable forces and the proposed solution will need to be re-thought.

Foundation factors are slow-moving

Particularly in international contexts, it is well worth looking into the foundation factors shaping observable behavior for insight into factors that will continue to affect product plans for years to come.

For example, much has been written about gift-giving practices in Japan (Rupp, 2003, Befu, 1986). But most studies haven’t addressed that behavior around travel gift-giving in Japan is heavily influenced by, compared to the USA, a relatively static labor market (people tend to stay at the same company) and relatively static real estate market (people often remain in their locales). When traveling ‘away from the group’, acknowledging the support of the group by bringing back small gifts for neighbors, friends, and co-workers is important to reinforce these often long-term relationships. When the foundation factors change, the behavior changes, as can be seen in the comparative infrequency of gift-giving between Tokyo neighbors in high-turnover apartment buildings. When the foundation factors remain the same, the same forces will continue affect situations for decades or more. It can be helpful to identify and understand the foundation factors affecting domains in order to know what observable behaviors and attitudes are likely and unlikely to change in the near term.

CASE STUDIES IN IDENTIFYING FOUNDATION FACTORS

The following case studies illustrate how foundation factors plays a key role in illuminating attitudes and mindsets, and explaining how aspects of workflows and behaviors arise.

Case 1: How European train maintenance workers share acquired expertise

While conducting ethnographic research of train vehicle maintenance in a European depot, we observed that one of the key challenges maintainers face is getting the information needed to accomplish repair tasks. Maintenance windows are limited. If they fail to return the train on time the maintenance company must pay a penalty. Past reference cases for identifying faults are stored in a computerized system, and the original client request was for ethnographic research to identify issues with the computerized system. The thinking was if the system were improved, repairs could be accomplished faster.

To fix a fault, the maintainer needs to find and review similar, past cases to determine probable causes. In addition to a hands-on check of the train, the maintainer must identify and reference past cases to assess whether the fault can be fixed at the depot or needs to be escalated to the manufacturer.

Although information on past faults is stored in the computerized system, the maintainers were not relying on the system to obtain the repair work information. In field research we observed that maintainers would seek out fellow maintainers with experience of similar cases, asking the informal network to identify who had encountered a comparable case. Our key finding was this informal knowledge exchange, in reality, was the primary method of obtaining needed information, and the key to successfully completing repair tasks on time.

As stated, our client thought that improving the knowledge sharing system would close the knowledge gap amongst maintainers and speed up the repair tasks. However, our research showed this would not work. The maintainers didn’t want to share their knowledge in a computerized system. Each maintainer believes their value in the railway maintenance labor market is determined by their troubleshooting expertise. In the European system, when an expert maintainer shares their know-how informally with colleagues, their reputation and status is enhanced. Simultaneously, expert maintainers believe that if they share their acquired know-how through a formalized system and their know-how becomes available to all, their market value might be decreased.

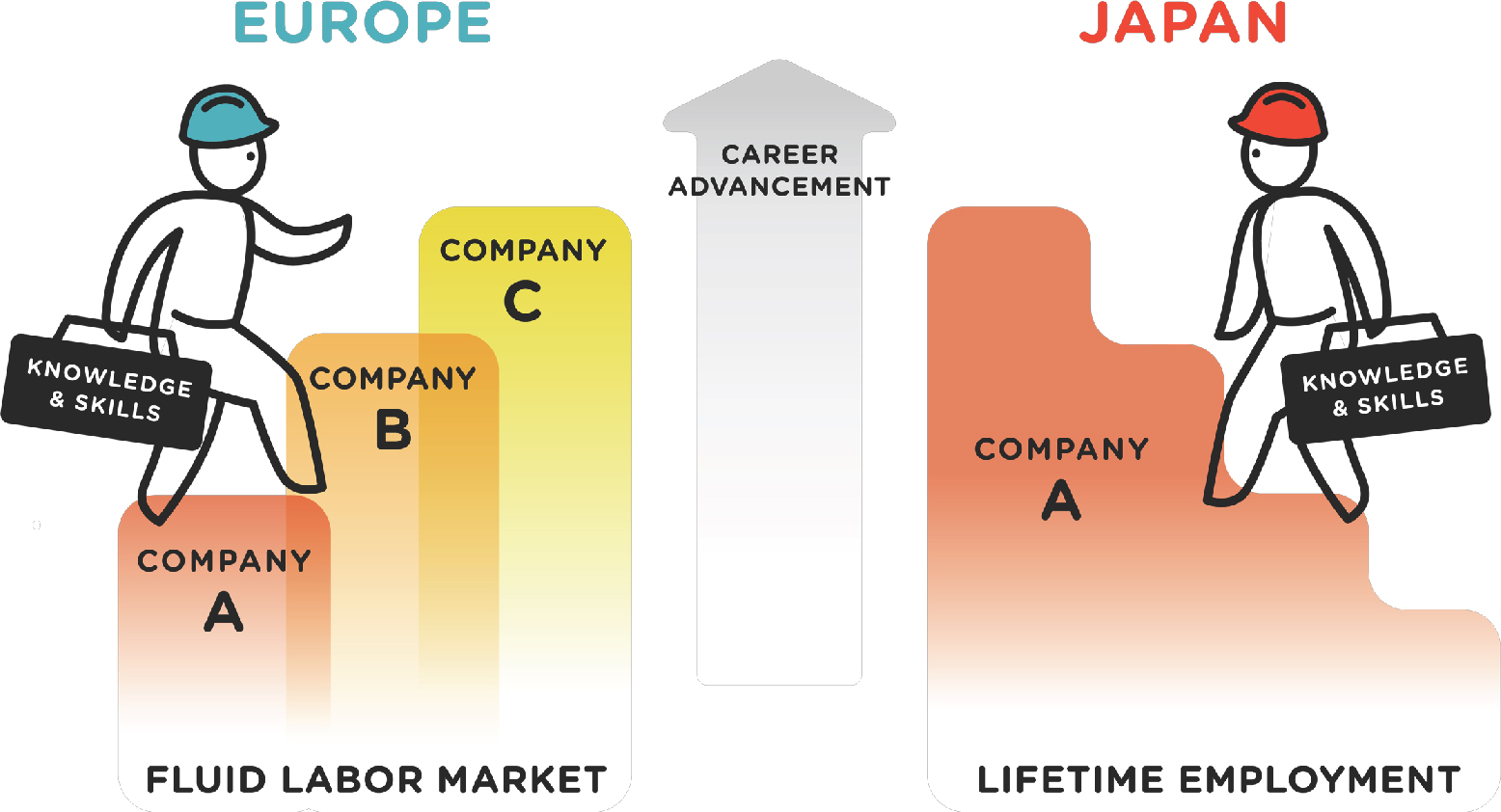

The foundation factor shaping this phenomenon is found in the fluidity of the European train maintenance labor market. The career cycle is: work in one company for several years; accumulate achievement & reputation. In order to achieve promotions and raises, maintainers must move to another company. By contrast the Japanese train maintenance labor market is based on lifetime employment. Sharing expert knowledge is regarded as an organizational asset and is a factor in promotions. Because Japanese train maintenance workers benefit, the workers are willing to share their acquired know-how through a formalized system.

Figure 2. The fluidity of the labor market affects how workers behave to advance their careers

The realities of each country’s labor market result in differences in what workers pride themselves on, leading to different attitudes and behaviors in where and how to share knowledge. In the European system the need for employment mobility to get promotions, and subsequent need to establish a reputation for personal expertise act as disincentives for maintainers to share acquired know-how in a formalized system. Describing the differences as cultural would not explain how heavily the behaviors and attitudes towards knowledge sharing practices between European and Japanese train maintenance workers are shaped by the underlying labor market. Lacking information on how the two different labor markets shape career paths and worker rewards, there is a risk that the client might invest in the wrong solution.

Case 2: Why Japanese and European train maintenance workers have evolved different skill sets

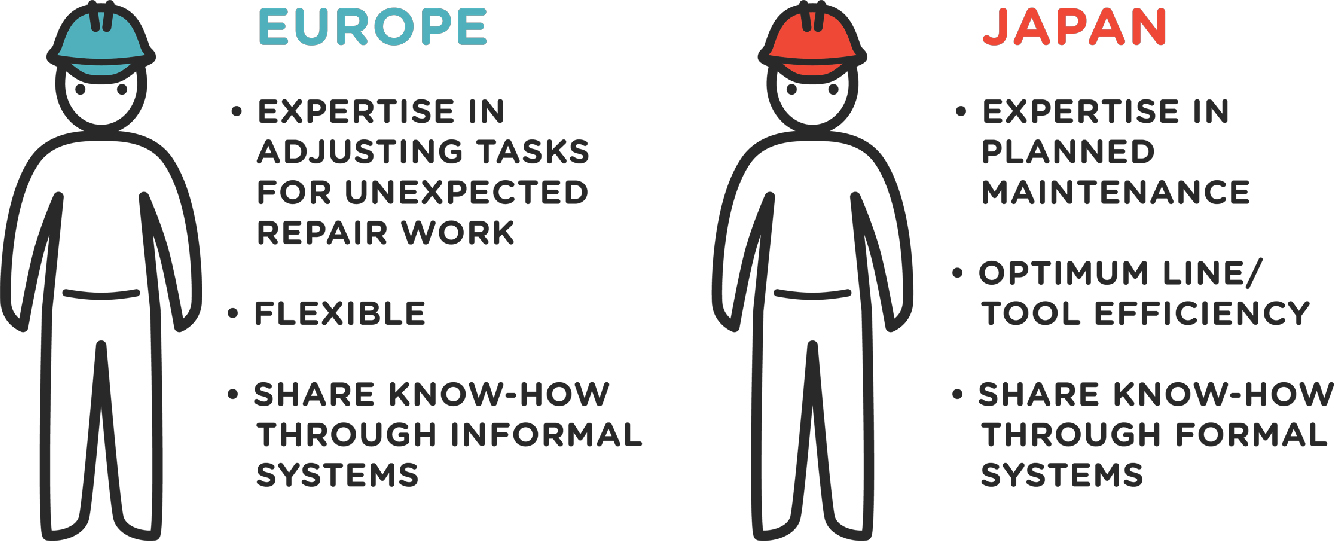

When conducting ethnographic research of train repair work, the differences in the focus of the work between Europe and Japan were notable. In the European rail sector, the priority was on repair work efficiency. In Japan, the focus was on planned maintenance. This difference in focus shapes how individual maintainers in each country develop their skills.

For example, European maintainers are experts at adjusting tasks when unexpected repair work appears. In order to effect the repair in time, they flexibly sub in a maintainer on the fly who’s familiar with that particular repair, and adjust the order of ongoing tasks to accommodate the sudden repair work. These are all informal skills developed onsite.

Figure 3. Optimizing tool placement

In Japan veteran train maintainers have expertise in accomplishing planned maintenance work as perfectly as possible through developed know-how such as where to place tools for optimum line efficiency. For Japanese maintainers, the emphasis is on developing skills for planned maintenance work rather than repairs.

Figure 4. Foundation factors such as financial schemas affected by government policies shape skills workers develop

What is the cause of this difference? It’s not simply, for example, that Japanese workers are detail-oriented and order-oriented; neither is it that European workers are flexible and cleverly adjust work tasks to fit the occasion. Behind these work practices is a difference in the financial schemas, leading to a difference in business strategy between Japanese and European rail sectors. Due to deregulation, separation of railway infrastructure and operations are common in European railway sectors. For example, in the European case the rolling stock ownership company, train operating company, and train maintenance company are different business entities. The train maintenance company contracts with the train operator. After maintenance or repair, the maintenance company is obligated to deliver the train at a specific time and place; they face a fine if they fail to meet obligations. Maintenance companies want to avoid the penalties. So rather than focusing on planned maintenance work, more effort is invested in unplanned repair work. Repair work is a primary factor in creating work delays, and it’s in their financial interest to avoid the hefty penalties. Therefore, experienced European individual maintainers informally develop situation-specific adaptive know-how in order to complete repair tasks on time. Additionally, European train operating companies approach maximizing profit by prolonging the lifetime of train vehicles with repair work; with older rolling stock, European train maintenance companies face more repair work.

By contrast, in Japanese train sectors there is no separation of railway infrastructure and operations. Train ownership, operation, and maintenance are managed within a single company. Because it’s all the same company there are obviously no penalty payments for late repairs. The Japanese approach to maximizing profit includes introducing more new trains in order to minimize repair work. Combined with the focus on planned maintenance, this business strategy is one of the key reasons behind Japanese train punctuality.

The two different business strategies, originating from different business and contractual obligations, directly affect the work practices and the skills maintainers develop. While one can say it is true in general that Japanese people tend to value order and many Europeans in contrast tend to be comfortable with making necessary adjustments on the fly, it would be misleading to chalk up the vastly different work practices to cultural differences. Investigating the foundation factors of the financial and business models — following the money — was the key to understanding this phenomenon.

Case 3: How foundation factors affect the design of Japanese magazines

Observing Japanese magazine staff working on new issues, one notable aspect is how much time and effort the editorial staff put into fresh layout designs for the feature articles. American magazines also change designs for feature articles, but to a far lesser degree. Why does the entire editorial room in Japanese magazines work so hard to create original layouts, breaking their own magazine’s grid, issue after issue? It’s true that there are many talented Japanese graphic designers. And the readership is responsive to design; perhaps it’s an symbiotic pact between magazines and readers. And perhaps Japanese magazine staff are singularly committed to their art, working into the night long past the hour the trains stop running. The determining factor lies not in these cultural differences, but in the underlying business model.

For purposes of comparison, the prototypical American business model for general-interest magazines is based on advertising sales. Magazines with high circulation numbers can sell advertising for high figures. To achieve high circulation, magazines offer yearly subscriptions for an enormous discount — discounts of 80% or more from the newsstand price is typical. Readers are incentivized to renew subscriptions with increasingly inexpensive offers in order to keep circulation high. Additionally, American magazines sell their large circulation lists to other companies so having a great many subscribers, while making no money from subscription fees, yields two-fold benefit to the magazine publisher.

In Japan, the business model is based on direct sales from newsstand competition in addition to advertising income. Unlike in the US, subscription discounts at 5% to 9% are so negligible as to not present a significant incentive. Subscribers are rare. Advertising rates do not jump based on circulation numbers, but advertisers can be impressed with an issue that sold well. The business goal is to sell as many copies on the newsstand as possible. In order to achieve newsstand sales, magazine editorial staff put a great deal of effort into appealing, innovative layout designs. One senior magazine design manager described the goal as creating fresh, surprising designs in order to interest would-be buyers.

This “battle at the newsstand” business model has direct implications for desktop publishing (DTP) software design. A key selling point for DTP software in the USA is the ease of creating, saving, accessing, and automating layout templates. While large parts of Japanese magazines are templatized, improvements to the template feature is not a strong selling point in Japan per se. One president of a magazine company half-jokingly said in order not to hurt sales, he wanted to ‘tear the template feature out’ and have his designers design everything from scratch. In his view the further his designers got from paper and pencil the more the designs suffered. In the context of the Japanese magazine business model, features that support quicker design experiments and side-by-side comparisons between layout candidates would be gladly received in the Japanese market.

There are additional foundation factors at play. Geographic realities such as the sheer size of the USA make regular, convenient access to newsstand sales difficult for much of the population. The small size of Japan and mature distribution channels which excel at stock management allow for the vast majority of the population easy access to newsstands, bookstores, train station kiosks, and convenience stores.

With creative work in particular, it’s tempting to look at design differences and draw conclusions about cultural differences. Some books and workshops on international UI design encourage UX professionals to do just that; a typical exercise is to examine the same company’s in different countries and note the visual differences to infer insights into that country’s cultural values. While visual differences can provide clues to areas to research, the ethnographer who is overly distracted by the cultural differences inferred from visual treatment differences risks missing the underlying structures shaping the design practices.

To illustrate the point, many Westerners perceive Japanese websites as “busy” in comparison to the current Western ideal of clean design (one current example is www.rakuten.co.jp). There are some cultural differences such as a preference for willingness to read more text, a historical enjoyment of the ‘busy marketplace’ idea, and a preference for democracy of information all one main page as opposed to hierarchically hidden. And there are other factors such as the fact that most web access is done from mobile devices not PCs. However, far more important and less immediately obvious are two underlying factors. One, the Japanese language is hard to use for text search so Japanese websites tending to be built for browsing. Two, Japanese websites visually reflect the structure of corporate Japan. Each department has a voice in the design of the website, which often translates to each department’s areas represented on the main page of the website. The design of work in Japan — internal structure and internal approval processes — and the constraints of the written language directly affect what the consumer sees on the page.

FROM FINDINGS INTO ACTION: INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH AND DELIVERABLES

There are several issues researchers presenting international studies must think through. One is how deep an explanation needs to accompany each aspect of the findings. Often the client has limited understanding of the international market, and doesn’t know what they don’t know. In international research almost all aspects would benefit from illumination, but as all user researchers know, corporate ethnography operates under extremely tight deadlines.

Client attention spans can be limited and crisp summarizations of key facts and recommended actions are often well-received. The benefit of including a good deal of foundational explanations is that long after the technology or system being studied is gone, research findings that include explanations of foundation factors can remain valid. The understructure is slow-moving compared to directly observable phenomena.

In order to dispel hidden home-market based assumptions, the international researcher must make explicit what is implicit. As other have noted (Cuciurean-Zapan, 2014) there can be assumptions hidden even in target market segmentation. For example ‘Professionals using presentation software’ likely contains assumptions about work practices and worker motivations when the client is based in the USA. In the client’s view, impressive presentation creation and delivery is important to professionals at work. This situation is connected to the very fluid labor market in the USA. This fluidity of the labor market means that professionals have the desire and opportunity to advance their personal career, partially achieved through honed skills and (regarding presentation software) looking polished in front of upper management. Where the labor market is less fluid, the meaning and purpose of presentation software will vary.

Additionally, market segmentation itself has varying validity from country to country, and clients are often unaware that their segments may not work overseas. The international researcher must determine if the right segment is being studied; one way to do this is to cast a wide net in exploratory research. A simple example from a case study in internet café research in China: “Initially, I approached him for help in recruiting small, medium and large-sized iCafes. But he stopped me short saying, “I have different way of categorizing the iCafe market. If I were you, I’d look for ‘luxury’, ‘common’ and ‘dirty’ iCafes.” (Thomas & Lang, 2007)

A common situation for international UX researchers is being asked to construct personas. Personas are synthesized composite characters based on real research, combining key aspects of product or service usage into a single ‘person’ or persona. The personas are named and serve as archetypical shorthand representing different user types in the development process, so stakeholders with different backgrounds can come to consensus during project planning, and so different user needs are represented during development. For example, a persona for a child’s car seat might be a single mother handling car-based daycare drop-off and pickup, and their concerns, motivations, and goals. While it’s unclear how much personas are actually used, some clients and development teams consider personas a project requirement. However, personas don’t work to summarize international findings and contribute to possible mis-direction. Why?

One, as mentioned above, segmentation is often different –– and often unrecognized as different –– for international markets. International personas are often expected to live neatly inside a framework based on domestic segmentation.

Two, more importantly, personas are by nature a type of shorthand. They rely on a shared understanding of the foundation factors, since goals and motivations are spelled out but not differences in underlying factors. As described above, mindsets, attitudes, and motivations are products of the foundation factors and can’t be separated from the underlying context or they lose meaning. In relying on shared context as a shorthand, personas strip away the foundation factors that are essential to understanding the actual situation. Accordingly personas are not of help in generating solution ideas, or providing actionable insight, when the personas and the client stakeholders do not share foundation factors.

CONCLUSION

In international business ethnography, in lieu of focusing on cultural differences to explain behaviors and workflows, looking in-depth at foundation factors can be illuminating and contribute to the long-lastingingness of research results. This paper has described in case studies how researching and understanding the foundation factors can help avoid errors of attribution and false cause and effect, as well as clarify for researcher and client what observed workflows can be changed, and what can’t.

Business ethnographers often have very little time to plan, complete, and report fieldwork. We need to be quick and accurate, delivering the kind of quality findings that lead the client to the right next step. In our experience, examining the foundation factors underlying local behavior and mindsets can be the fastest path to actionable insights and goals.

Yuuki Hara is a user researcher at Hitachi, a large multinational company based in Tokyo. Hara manages a team that conducts ethnographic studies of work places in various domains. Through capturing work practices in actual settings, Hara and her team uncover how hidden factors relate to the business goals.

Lynn Shade is a UX research & design consultant who grew up in Japan, worked as a designer at Apple and Adobe, and returned to Japan after 20 years in Silicon Valley. Shade specializes in creating design strategy through discovery research and design.

Illustrations by Akiko da Silva

NOTES

Special thanks to: Wilson Chan, Sheryl Ehrlich, Yoshinori Kikuchi, Priscilla Knoble, Akiko da Silva, Britton Watkins

The views in this paper do not represent the official position of our past or current employers

REFERENCES CITED

Anderson, Ken, Faulkner, Susan, Kleinman, Lisa, and Sherman, Jamie

2017 Creating a Creator’s Market: How Ethnography Gave Intel a New Perspective on Digital Content Creators. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings Volume 2017, Issue 1

Befu, Harumi

1986 Gift Giving in a Modernizing Japan. Japanese Culture and Behavior: Selected Readings edited by Takie Sugiyama Lebra, William P. Lebra. University of Hawaii Press

Cuciurean-Zapan, Marta

2014 Consulting against Culture: A Politicized Approach to Segmentation, Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings Volume 2014, Issue 1

Ferreira, Alberto

2016 Universal UX Design: Building Multicultural User Experience, Morgan Kaufmann

Graham, Connor, and Rouncefield, Mark

2010 Acknowledging Differences for Design: Tracing Values and Beliefs in Photo Use, Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings Volume 2010, Issue 1

Hall, Edward T.,

1976 Beyond Culture. Anchor Books

Hofstede, Geert

2001 Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ikeya, N., Vinkhuyzen, E., Whalen, J., & Yamauchi, Y.

2007 Teaching Organization Ethnography, Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2007, pp. 270-282.

Mitchell, Don

1995 There’s No Such Thing as Culture: Towards a Reconceptualization of the Idea of Culture in Geography

Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 20, No. 1. Wiley-Blackwell (1995)

Nielsen, Jakob, and del Galdo, Elisa

1996 International User Interfaces. Wiley 1996

Randall, Dave, Harper, Richard, and Rouncefield, Mark

2007 Fieldwork for Design: Theory and Practice. London: Springer.

Rupp, Katharine

2003 Gift-Giving in Japan: Cash, Connections, Cosmologies. Stanford University Press

Sun, Huatong

2012 Cross-Cultural Technology Design: Creating Culture- Sensitive Technology for Local Users. Human Technology Interaction Series, Oxford University Press

Thomas, Suzanne, and Lang, Xueming

2007 From Field to Office: The Politics of Corporate Ethnography, Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2007, pp. 78–90.